CHAPTER XIII

Attempts To Revive Recruiting

The new Women's Army Corps began in spirit early in the summer, when groups of worried recruiting experts gathered in the Director's office to plan the first campaign. The whole future of the Corps quite evidently hung on the success of this effort. WAAC recruiting closed on 8 August 1943, and WAC recruiting opened without delay on the following day, yet in the entire month only 839 recruits were reported.1

At the same time, the Army's need for personnel had never been more urgent. The Adjutant General estimated that 2,000,000 more men must be drafted within the next year, of which 446,000 would be fathers of families. The Adjutant General stated that more than 600,000 of the jobs could more efficiently be done by Wacs, thus preventing the necessity of drafting any fathers whatever. General Marshall, after the ceremonies in which Colonel Hobby was sworn into the WAC, asked her if she could get the Army the 600,000 women it needed. The Director avoided a public reply.2

In fact, the real question was whether the WAC could survive at all, after the twin blows of the slander campaign and the conversion. In its first year, the Corps had recruited almost 65,000 members, but at the July recruiting rate it would take almost three years to get another 65,000; at the August rate, five years. At this point normal attrition overtook recruiting.

As the Corps waited for War Department solution to the recruiting problem, excess training centers were closed, surplus instructors were assigned to officers' pools, and recruiters were told to suspend their efforts pending new instructions.

The Search for a Recruiting Theme

In view of the gravity of the situation, both General White of G-1 Division and Brig. Gen. Joseph N. Dalton of ASF's Military Personnel Division personally participated in recruiting conferences during the summer. The ASF donated the full-time services of Ma;. Robert S. Brown rated as one of its best publicity experts, who was to give the problem concentrated attention until his death the following year. The advertising agency of Young & Rubicam sent numerous experts, including its adviser, Dr. George Gallup.

These planners fell into anxious debate over the theme of the next campaign,

[231]

which if not successful might well be the last. Dr. Gallup advocated an appeal to a woman's self-interest, with emphasis on the advantages of military status, the value of WAC training, and free clothes, food, and medical care. Colonel Hobby disliked such an approach, and held out for the straight patriotic appeal. Her favorite advertisement was a "shocker" which showed a wounded soldier dying on the battlefield while women played bridge, with the caption, MEN ARE DYING ON THE BATTLE LINE---CAN YOU LIVE WITH YOURSELF ON THE SIDELINE?

This approach was vetoed by Generals White and Dalton, who were obliged to inform Colonel Hobby that the censors forbade showing dead American soldiers to the American public. Colonel Hobby next produced an advertisement showing soldiers' graves, with the caption, THEY CAN'T DO ANY MORE-BUT YOU CAN. She argued, "Something like this is needed to drive home a sense of shame to women not doing anything." Results would be better, she said, "the more difficult this job was painted to a woman, the more of a challenge it was to her . . . telling how hard, how drab, how routine it is . . . . Has she the courage to do the commonplace as against the courage of the spectacular?" Dr. Gallup disagreed with her, saying:

When you take into account all groups, I am afraid that would not be as good as some other appeal. There is too much competition from other things; there are too many ways by which people can rationalize their own situation. Almost every person has, in his own mind, become important, even though only growing a couple of cabbage heads.

Representatives of Young & Rubicam pointed out also that "what appeals to the manufacturer seldom appeals to the consumer," and finally decided to run only one advertisement of the shocker type to see if it "made the women mad." Colonel Hobby replied that, as far as she was concerned, they could be made as mad as hatters if it only drove them to the recruiting station.3

As a matter of record, when the soldiers'-graves advertisement was used in October, it was banned in Boston newspapers because it was "too gruesome" and might have caused "sad week ends" to sensitive citizens. Most later advertisements therefore emphasized the WAC's attractive jobs and its material advantages.

It was decided that advertising emphasis would be put on, first, the hundreds of types of Army work now open to Wacs, and second, WAC benefits, which now offered the greater advantage of full military status. It was noteworthy that the same decision concerning "glamorization" was also deemed essential, at different times, by both British and WAVES recruiters, in both cases over the objections of women directors.4

Colonel Hobby took the occasion of her oath of office to launch another theme more congenial to the American public than the ill-fated "Release a Man" slogan; this was the WAC as the preserver of the American home. Pointing out that every

[232]

woman in uniform enabled a father to stay with his family, Colonel Hobby informed the press, "Women as a group have always been the exponents of family life. They may now preserve and protect this family life, the core of American civilization and culture."5 Newspaper writers readily took up this idea, stating, "In the absence of a draft, it is just possible that the WAC will be filled by young women who would rather join the Army than see their married brothers taken from their children." War Manpower Commissioner Paul V McNutt tentatively indorsed the theme, saying, "The number of Wacs and Waves has been increased. As a consequence the month when it would be necessary to take fathers has been pushed back. We do not yet know what the yield will be.6

This potentially powerful approach could not be pushed as far as was desired because of the refusal of the nation's highest manpower agencies to lend it any practical support. Attempts were made to get the national Selective Service system to credit WAC enlistments against local draft quotas instead of against national totals, so that women might see the results of their enlistment in their own towns, but this was repeatedly refused by Maj. Gen. Lewis B. Hershey because of the extra effort and the administrative changes involved.

The War Manpower Commission also, in spite of Mr. McNutt's public statement, continued to act on the assumption that WAC recruiting was a threat to the industrial war effort. 7 During these summer months, recruiters in the field forwarded surprising information concerning WMC's part in the recent failure of the Cleveland Plan. Colonel Hobby telegraphed all service commands for confirmation, and discovered that, during the Cleveland Campaign, the War Manpower Commission had effectively stopped all WAAC recruiting publicity in areas including about one half of the population of the United States.

The news appeared the more inexplicable in that the Cleveland Campaign had been cleared with national WMC headquarters before ever being launched. To obtain clearance, considerable concessions had been made by the armed forces in a joint Army-Navy agreement in April, in which they had renounced the right to recruit women engaged in aircraft production; shipbuilding, ordnance or signal work, war research and technical teaching, and wire or radio communication. Nevertheless, service commands indicated that, as soon as the Cleveland Campaign had been launched, the War Manpower Commission had directed its regional agencies not to allow the services to recruit any women, employed or unemployed, in labor-short areas.

While the WMC could not prevent recruiters from setting up offices in a city, it could, through its control of the Office of War Information, prevent them from making their presence known by way of radio, newspapers, or other news media. The OWI disclosed that it had received orders from the War Manpower Commission not to give any publicity to armed forces recruitment of women, and stated, "The War Manpower Commission is the ultimate authority on recruitment. The recruitment of women is limited to such areas as are agreed upon with the Re-

[233]

gional War Manpower Commission Office.8

These areas were extensive, containing perhaps one half the population of the United States. It was also discovered that almost all large cities had been included: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Indianapolis, Baltimore, and many others a matter that was serious to understaffed recruiting offices, since cities were the most easily accessible areas. For example, in New York state the OWI directed, "Recruitment of women WAVES, WAGS, SPARS, and Marines is not considered advisable in Albany, Buffalo, Rochester, Schenectady, Syracuse, Troy, Utica, and [other cities.]" The stoppage was the more inexplicable in that, while affected areas were chiefly those labeled Class I or II "labor-tight" areas-others were in Class III or IV, where there was supposedly no labor shortage.9

The Army at once took issue with this action, informing the War Manpower Commission that it was highly questionable whether the WMC Enabling Act gave the Commission the authority to limit recruitment of women by the armed forces. The executive order that gave WMC control of the Selective Service system directed only that "no male person," 18-38, should be inducted except through Selective Service. The WAC was not mentioned except that its training programs, with all others of the armed forces, should, if using nonfederal educational institutions, be co-ordinated to ensure full use. It did not appear to the Army that female soldiers could be considered "workers" in the passage which required "the hiring, rehiring, solicitation, and recruitment of workers . . . in any plant, facility, occupation, or area" to be done through the United States Employment Service.

In reply to the Army, the WMC retorted that WAC enlistments "shall be subject to the conditions of employment stabilization plans of the War Manpower Commission." It claimed authority not only over publicity media, but also to direct the Army not to send WAC recruiting teams to any area, or to use drill teams, bands, or local advertising, or to set quotas or take any other means of encouraging women to join the WAC. It also added thirty-five more exempted fields from which the WAC could not accept recruits, some of which were described in such broad terms as "industries" and "education services, public and private."10

The Army and Navy joined in protesting this action. They pointed out that it was extremely shortsighted to draft skilled male factory workers and teach them to type, thus forcing industry to replace them with women who had to learn the factory trade; both armed forces and industry would benefit by allowing a woman typist to enlist so that a skilled factory worker need not be drafted. Since competitive recruiting was admittedly to be deplored, the armed forces suggested instead a giant combined campaign, with resources of all agencies directed toward drawing women

[234]

MAJ. JESSIE P. RICE

into war work, with the choice of job left to the individual. Otherwise, the Army pointed out, many unemployed women in labor-short areas would never be reached, since they would not take factory jobs and could not be offered Army jobs.11

As the War Manpower Commission refused action, the armed forces in August appealed the issue to the nation's highest manpower authority Justice James F. Byrnes, the Director of War Mobilization. On 12 August 1943, the Director of War '.Mobilization informed the contenders that the WMC was forbidden to interfere in national recruiting campaigns even in labor-short areas. Its list of thirty-five essential industries was rejected in favor of the Army's shorter one of eight. The Army was in turn directed not to conduct any "intensive local campaigns" in Class I and II areas without clearance with the WMC. 12 It was only with this reassurance that the Army approved funds for the advertisements already selected, and for a new recruiting campaign to be co-ordinated with them. The campaign, unlike the advertisements, was shaped about the patriotic motif that the Director preferred.

Both the idea and the energy for the new campaign were supplied by a newcomer to WAC Headquarters, Capt. Jessie P. Rice of the Third Service Command, who was reassigned to the Director's Office in the summer. Captain Rice-a major in late August-was a woman of 42, described by reporters as "cheery, no-nonsense," and by all who knew her as "dynamic." She brought to the problem what proved an appropriate background-that of an industrial sales manager, history teacher, sports reporter, and native of a small Georgia town; she had also had a year's field experience as Staff Director, Third Service Command. For the next twenty months, first as head of WAC Recruiting and then as Deputy Director, she was to be, next to Colonel Hobby, the chief author of WAC policy. She was later credited by Director Hobby with, quite literally, saving the WAC from public defeat on two different occasions, of which the first was the present critical period. In her approach to the current problem, as to all later ones, staff members noted a rare combination of commonsense practicality with unabashed idealism

[235]

for the nation's goals and the Corps' contributions to them.13

Major Rice strongly believed that the WAC would achieve lasting success and overcome the slander campaign only through the support of the American community, which was merely alienated by dazzling super salesmanship and could be won only through giving community members a personal stake in the outcome. They must not be worked upon by outsiders but must do the work themselves, and its outcome must be made a competitive matter of local pride.

She therefore christened her plan the "All-States Plan" and credited the idea to a local success achieved by Baltimore recruiters. It called, quite simply, for each state to recruit a state company. which would carry its flag and wear its armband in training. The trick was in the mechanics, which involved participation of the states' most reputable citizens: General Marshall was to ask state governors to appoint local committees consisting of mayors and other prominent citizens in each town, who would be responsible for aiding recruiters to meet the quota. Major Rice said:

You will find in this plan nothing new-it is based on the oldest and most fundamental appeal any nation has ever used, and the device it uses is the oldest recruiting device in America, stemming from Colonial days. The appeal is the straight patriotic appeal . . . . By making this appeal by States we hope to reinforce it by the appeal of State pride. We have a big country with many state and sectional traditions . . . and they can be made to play their part only if the operations are conducted by people who know the States and the people in them.14

Another appeal was added by Colonel Hobby concerning the setting of the quota; each town would list the number of its sons who had become battle casualties and would recruit a woman to replace each.15

The All-States Plan, Major Rice predicted, would not bring in astronomical numbers of recruits, but it could if properly handled pull the WAC out of its recruiting slump, ensure its continued existence, and help to squelch the slander campaign.

The WAC recruiting machinery could scarcely have been in worse condition for a new effort. Recruiters had borne the brunt of a year of public hostility, and were so fatigued and discouraged that their relief would have been essential had any trained replacements been available. A typical example was one very junior North Carolina recruiter, who reported bitterly that she had made recruiting trips to all the main towns in nine different counties, secured severity-three free articles and advertisements, got free radio time, secured lists of prospects in every town and sent them all letters, developed a trailer film and display boards, sponsored a state-wide high school poster contest, and distributed 10,000 copies of the winning poster. In return, she succeeded in giving out only ninety application blanks, received thirteen applications, and enrolled two women. Meanwhile, her four enlisted assistants became discouraged

[236]

and applied for discharge from the WAAC to get defense jobs in California. For these tribulations, her only reward was a letter of reprimand from WAAC headquarters concerning the winning poster, which had been in such poor taste as to come to national attention.16

The burst of energy demanded by a new recruiting drive therefore presented a particular problem. Colonel Hobby wrote to the discouraged recruiters:

I know the difficulties, the loneliness, the heartbreaking apathy you have faced. I know how hard it is, after weeks and months of discouragement, to clip deep into inner resources and start again with fresh enthusiasm. But I know, too, that you have such inner resources . . . . If you can give fully of your own strength, your own conviction, your own faith and heartfelt patriotism, we will not fail now.17

For the success of the campaign, the WAC leaders depended frankly, as always in the Corps' history, upon these "inner resources," and upon motives which were matters of ideals and spirit. Major Rice took charge of the hundreds of conferences and interviews required by the All-States Campaign, quoting freely from Torn Paine concerning "summer soldiers and sunshine patriots," and using a modern quotation also favored by Colonel Hobby as typifying the Corps' present slim chances of success:

God of the hidden purpose

Let our embarking be

The prayer of proud men

asking

Not to be safe, but free.18

As the Corps poised upon the threshold of this crucial effort to restore itself, Major Rice informed a conference of service command recruiters:

We know that there are millions of women who will join us now, if we can touch that spring of inner compulsion that causes people to forget self and fear of the unknown and strike out along the path that leads to their ideals.19

The campaign's organization was nevertheless highly practical, and was to stand as a model for all future efforts. to avoid misunderstandings, Army recruiting and induction officers from each service command and their WAC assistants were thoroughly briefed in a Washington conference on the entire plan. At the same time, the Army's Recruiting Publicity Bureau, in New York City, set its presses rolling to produce, in an unprecedented short time, portfolios of instructions for recruiters, with brightly colored and attractive posters, window cards, stickers, manuals, envelope stuffers, clip sheets, mats, and advertisements of all sizes.20

Also, the War Advertising Council was approached and agreed to arrange free sponsored national advertising for the WAC as it was doing for other agencies. Recruiters were also instructed in how to get free advertising on a local level; many firms were found to be willing to aid the war effort by contributing advertising space, or by including a Wac in their usual advertisements. Many posters and other aids were also sponsored by various business groups. For example, the Stand-

[237]

and Oil Company of Indiana sent its dealers 19,000 posters, "The Girl With the Star-Spangled Heart," to replace the previous "Drain Old Oil Now." 21

National civic and business organizations by the dozen were approached by Colonel Hobby's staff and agreed to mention the WAC in their trade publications and bulletins: the American Retail Association, the National Dry Goods Association, the National Association of Theater Owners, five press associations, most magazine publishing firms; several film companies, the Mayor's Conference, the National Association of Broadcasters, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and others as varied .22

Organized club women of thirty-six national organizations announced their support after visits of their representatives to Des Moines.

The Executive Committee of the Governors' Conference also gave a preliminary indorsement which assured the Army that state governors would respond when officially called upon.23

Paid advertising was also authorized to supplement all the free publicity that the above agencies could contribute. Colonel Hobby asked that the Army allot $10.00 per needed recruit for this purpose, chiefly for systematic coverage of Sunday, newspapers. General Dalton disapproved this on the grounds that "no business which is forced to operate at a profit would consider such an appropriation,"' but he was overruled by General Somervell, who considered that the situation merited the expenditure. As a matter of fact, the sum was somewhat less than that later used in postwar Army advertising to get comparable numbers of male recruits.24

As an added precaution Director Hobby in two different meetings with high War Manpower Commission officials cleared the All-States Plan. She was informed that, from 27 September to 7 December, recruiting was authorized even in Class I and II areas, provided that no woman was taken from essential industry. A representative of WMC likewise stated this fact in a speech to the recruiters conference, and the Army published it to recruiters. In return the Army agreed to urge rejected WAC applicants to accept factory work.25

Because the WAC's continued existence was virtually staked on this one campaign, the War Department decided to accept assistance from a source that it had previously rejected-the Army Air Forces. The AAF had for months begged to be allowed to send out its own personnel to assist regular recruiters, the only proviso being that recruits so obtained could be promised assignment to the Air Forces. Such special-promise recruiting was not unknown to the Army; the Air Forces' recruiting teams, in a recent campaign to get 57,000 male aviation specialists, had

[238]

recruited 128.000 almost before the campaign could be shut off. Nevertheless, Colonel Hobby had consistently rejected these offers, pointing out that special promises to recruits-their choice of branch or station-were undesirable and that difficulty and hard feeling would later result, particularly since earlier recruits had no such choice .26

Army Service Forces recruiting experts now informed Colonel Hobby that the WAC would have to abandon its stand against special promises, saying, "The persistent decline in WAAC recruiting results; along with the increasing need for women in the Armed Forces, make it essential to open the door immediately for special WAC recruiting plans." 27 It was therefore decided to adopt the Air-WAC Plan to supplement the All-States Plan; the Air Forces would not compete, but would bring in women who would be part of the state companies until trained. Branch recruiting thus became an accepted fact, although the other two Army branches -AGF and ASF- did not at this time decide to give any personnel to the project. The AAF at once prepared to throw hundreds of additional recruiters into the struggle.28

On the eve of the campaign, Major Rice estimated that the take would be 10,000 in the approximately two months between 27 September, when the campaign opened, and 7 December, when it closed. Colonel Hobby optimistically hoped for 35,000, and asked that Fort Sheridan be made available in case the three remaining WAC centers were inadequate. The Adjutant General insisted that the higher goal of 70,000 be set, since 70,000 casualties had been sustained to date. Colonel Hobby deplored this move, saying; "It is negative psychology to have an impossible quota''"; she recommended a quota of approximately 17,000 for the entire period, which was disapproved by the Army Service Forces. Major Rice attempted to use merely the number of those killed in action instead of all casualties, but the number 70,000 was chosen by the Secretary of War and used in all publicity releases. Actually, G-3 Division of the War Department had hopefully included 200,000 Wacs in the Troop Basis for 1943, but with the provision that more men could be drafted if women failed to volunteer. The most impossible figure of all came from The Adjutant General's Office, which calculated that 631,000 Wacs were needed at once to prevent the drafting of fathers. The figure of 600,000 was used by General Marshall in his public speeches, to emphasize the extent of the Army's need, but was never considered a real quota.29

On the last day of August 1943, the All-States Campaign went into action with the precision and co-ordinated effort of a

[239]

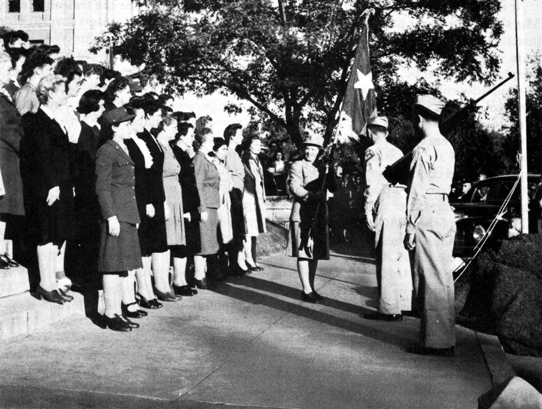

ALL-STATES RECRUITING CAMPAIGN. Governor Leverett Saltonstall of Massachusetts cuts the ribbon opening a WAC recruiting booth. Standing next to the Governor is Mayor Maurice J. Tobin of Boston.

military invasion. Exactly twenty-seven days were allotted to softening up the public before the recruiters landed. General Somervell opened the barrage on 31 August with a personal telegram to the commanding generals of all service commands stating, DIRECTOR HOBBY WILL CONTACT YOU ON WAC RECRUITING PLAN WHICH HAS MY APPROVAL. URGE FULL SUPPORT. On the same day and the next, Colonel Hobby made personal long-distance telephone calls to these commanding generals, explaining the plan. In the following week, full details were placed in the hands of recruiters assembled in Washington. 30

On 10 September, General Marshall sent a personal letter to each state governor, saying, "I am appealing to you for assistance . . . ."31 This was followed by immediate visits to the governors by service command representatives. In the

[240]

ALL-STATES RECRUITING CAMPAIGN. Texas state flag is held by a WAC officer during a ceremony for recruits in front of the Stale Capitol, Austin, Texas.

Seventh Service Command, Maj. Gen. Frederick E. Uhl took a plane and personally visited each state. The governors' responses were in most cases immediate; they appeared eager to be called upon for a further part in the war effort. Many issued proclamations such as

Whereas the successful prosecution of the war requires the enrollment of adequate manpower and [five other whereas's ] . . . . Now therefore I, John W. Bricker, Governor of the State of Ohio, do hereby call for volunteers for service in the WAC . . . . I do further call upon mayors and other governmental authorities . . . upon all citizens, newspapers, and radio stations . . to the end that the State of Ohio may fully achieve her goal in this great national objective.

The governors appointed committees in every community, consisting ordinarily of local officials and prominent citizens, whose efforts were co-ordinated by WAC recruiters. Many governors and mayors allowed the use of their names in local advertisements, for example:

WOMEN OP FITCHBURG

A Message from your Governor:

Throughout the history of America, men and women of the Commonwealth have never failed to answer the call of service to their country . . . . I am confident that once again the daughters as well as the sons of Massachusetts will have proved their right to our great heritage.

[Signed] Leverett P. Saltonstall

[241]

At the same time, the weight of General Marshall's personal prestige was thrown into the campaign in a national press release which, on 15 September, described the plan to the public. This was supported by paid advertisements on a co-ordinated theme placed in Sunday papers by Young & Rubicam.32

On 27 September, the doors were formally opened to All-States recruits. An unprecedented concentration of recruiting activity resulted: it appeared doubtful that any inhabitant of the United States failed to hear of the WAC if he could read, listen to the radio, or be reached by a citizen's committee. The Office of War Information for the next three weeks devoted to the WAC most of the free facilities offered it by radio stations, ordinarily used for such projects as bond sales and food conservation; 17,000 messages were broadcast over 891 radio stations, plus 150 plugs on network programs and special, national, and spot programs. The Army Air Forces on 18 October threw teams totaling 358 officers and 1,136 enlisted personnel into the campaign. The WAC Band toured; governors continued to issue statements, which Young & Rubicam caught up and published: governors whose states led were congratulated, others were chagrined, and some even went on Personal speaking tours. In general, recruiters seasoned by earlier campaigns seldom fumbled, and publicity was uniformly good.33

State companies were shipped to training centers as fast as enough for a company were recruited. The women were ordinarily assembled at the state capitol building or some other historic spot, where they were sworn in with much ceremony, martial music, parades, crowds, and publicity, and presented by the governor with a state flag to carry at the training center. Some states thus recruited several companies in succession. No one WAC training center had sufficient capacity to hold forty-eight companies, but the spirit of the idea was preserved, and each training center parade had a display of from fifteen to twenty state flags. Competition among state companies was keen, and most recruits were kept in a state of high morale by the favorable attention given them by home-town newspapers and by their introduction to the governor and to other prominent citizens.34

Altogether, WAC and Army authorities were highly pleased with the prospects. Colonel Hobby called the plan "the best recruiting device we have ever had." The campaign seemed well on the way to achieving some of the more optimistic predictions. Well-nigh faultless in its organization, and highly effective in achieving the desired effect upon the public, it appeared that it could have been stopped only by one thing-an order from authority higher than the Army. And this was, in effect, what stopped it in many areas.

Opposition of the War Manpower Commission

No sooner was the All-States Campaign well launched than the Army discovered

[242]

that the War Manpower Commission was again ignoring not only its two agreements with the Army but the August directive from its superior, Director of War Mobilization Byrnes. In spite of WMC clearance of the All-States Plan, regional WMC offices in five of the nine service commands not only suppressed local WAC recruiting publicity, but, speaking as "The United States," released headlines such as one in Connecticut: U.S. FORBIDS WAC DRIVE IN CITY AS THREAT TO WAR EFFORT. In Macon, Georgia, bewildered recruiters were confronted with an ultimatum from the WMC area director saying, "I have decided it would not be feasible to continue with this [recruiting] program. This is a result of Macon being an extreme labor shortage area, and every woman who would be acceptable to the WAC could be used to advantage in war industries." The Office of War Information withdrew radio support in such localities as directed by local WMC officials saying that it had no other choice.35

The most charitable interpretation that could be put upon this action was that the War Manpower Commission had been slow in informing its regional offices of the Byrnes decision and of its own official clearance of the All-States Plan. When questioned by telephone, WMC officials at first gave this explanation, saying, "Frankly, they should have gone out quite some time ago." However, a few days later an executive staff meeting was held, of which Major Rice was informed, "Fact is, it was a complete nullification both in the chairman's office and the executive staff of the things we had discussed as exploratory." Major Rice at once pointed out that the WMC's commitments had not been exploratory, that WMC representatives had stated them at official meetings, that the Army had spent a million dollars and staked the Chief of Staffs prestige upon them, and that "we are in a pretty desperate condition, with time running out on us."36

Director Hobby called to the War Department's attention "the fact that we had begun the All-States Campaign believing that we had clearance . . . the fact that with the best recruiting device we have ever had, we have been barred by the WMC area directors from making any effort to reach many thousands of women in areas of essential industry who are not themselves engaged in essential industry.37 High-level negotiations with the War Manpower Commission began again. The WMC now refused to inform its area directors of its previous clearance of the All States Campaign unless the Army agreed to use the WMC list of thirty-five essential industries. which Director Byrnes had already disapproved, instead of the shorter Army list which he had approved. Mr. McNutt's office also demanded that its area directors be given power to add industries to the list at their discretion, to veto any objectionable activity, and to supervise all WAC advertising copy.38

Rather than thus renounce the advantages that the Byrnes decision had decreed for it, the Army chose to fight the matter

[243]

through. The negotiations dragged on for some time and were not to reach a workable conclusion until the following year. Meanwhile, the brief All-States Campaign, which had depended for effect on its impetus and concentration, was somewhat blunted in many areas, and reached its final deadline on 7 December without feeling any benefit from the negotiations.

There was no way of computing the exact loss which had been occasioned by the War Manpower Commission's action. Major Rice believed that it was perhaps not as serious as the initial setbacks had indicated. In any case, it was clear that while the Army had at last made plain to the public its united support of the WAC, the government as a whole had not done so. Instead, the nation had approached a grave emergency without any clear definition of the role of womanpower and its apportionment among competing agencies.

The lack of support by civilian manpower control groups of the United States Government explained to some degree the public conviction that the matter was not important, and the resulting apathy, which recruiters encountered as the All-States Campaign drew to a close in early December of 1943. One annoyed general reported that in his service command there appeared to be three types of women: (1) patriotic, who had already taken essential civilian work or enlisted in the WAC; (2) patriotic but mercenary, who were interested only in the highest-paying war jobs; and (3) "The leisure class, who like to go down to the USO, dance with the boys on Saturday night, and think they are making their contribution to the war effort that way. They make all these talks, appear in theaters, put up placards, appear before women's clubs, talk to everybody in the world, but when it comes to getting them to sign up, they say no soap."39

The Army's highest-ranking officers now became personally aware of the factors affecting WAC recruiting as never before in the Corps' career, since the All-States Campaign put the responsibility upon them as well as upon community leaders. General Dalton personally telephoned the commanding generals of service commands to read them a long list of ideas to get recruits. He told each pointedly, "I wonder if you've gotten word down to all ranks that General Marshall and the rest of the top people have an intense interest in this WAC recruiting."40

The difficulty in getting a woman recruit at first amazed, then exasperated, then spurred to action the commanding generals concerned. Even the service commander who led the field was dissatisfied and observed to General Dalton: "I don't know what is wrong. It just doesn't seem to take . . . . Well, we will put all we got in it, Joe." Another visited WAC recruiters at work and reported that "these people are up against a hard proposition" and needed all the co-operation that the Army could give. Still another noted how high paying industry had stripped the area of qualified women, and stated, "If they're not just children, overaged, or a little moronic or something, they've quit, they've gone away." The interest and indignation of these officers worked to the WAC's advantage in that, recruiters reported, they were now able to get from their headquarters better transportation,

[244]

personnel, and station locations than had previously been made available.41

The Army Air Forces recruiters received a similar shock. Employing tactics that had recruited 128,000 male mechanics in a short time, they were able to get, in the entire month of November, only about 1,500 Wacs. One AAF officer reported:

I never saw anything as tough. When our team hit one Florida city, we closed the place-actually got the mayor to close schools and stores so everyone would come to our parade and rally. We got important speakers, generals, war heroes. Better than 50 planes flew overhead forming the letters WA C. That night we had a big dance for prospects, with good-looking pilots as dates. Results? We didn't get one Wac in that town. Some of the local girls put in applications to please their escorts, but withdrew them the next day.42

It soon was apparent to the Air Forces that there was one important difference in the mechanics' campaign and the WAC campaign-the men had been faced by eventual draft and so had been happy to have a choice of branch, job, and station near home, whereas the women were not faced by any such compulsion. Nevertheless, the Air Forces persisted, and by December were getting more than half of the total intake.43

The Success of the All-States Campaign

In spite of the opposition of the War Manpower Commission and the public apathy, the All-States Campaign proved the most successful the Corps was ever to undertake. The intake of 4,425 in its final month was better than anything that had ever been achieved with comparably high enlistment requirements.44 The final tally showed that the drive had netted 10,619 recruits, slightly over the 10,000 that Major Rice had predicted. No later campaign, even the highly successful General Hospital Campaign in 1945, was ever to achieve equal numbers in so short a time.

Even better than its immediate results, in Colonel Hobby's opinion, was its continuing effect in overcoming the slander campaign. Major Rice praised the "wonderful civilian cooperation, that will reap results for months to come."45 A new Gallup survey in the closing months of the year showed that, the Director stated, "Public attitude is now definitely favorable to the WAC-more so than at any time since its organization."46 Surveys showed that, among eligibles, 83 percent now knew that the WAC was part of the Army, and 85 percent knew that the WAC needed more women. When asked, "Which service needs women the most?" eligibles replied: WAC-58 percent; WAVES-14 percent; Marines-14 percent; SPARS-4 percent; Don't know-5 percent. If drafted, women stated that in making a choice they would give the WAC a slight edge on other enlisted women's service.47

General Dalton, while objecting to the cost per recruit, stated that the campaign had led to a better organized and successful recruiting service. Recruiting proved to be permanently restored, even though

[245]

to a modest level, and was to average more than 3,000 a month until the last days of the war. The campaign had thus answered the question of whether the WAC could survive: it could. On the other hand, the days of expansive planning in terms of millions were obviously ended, although it was always difficult for planners completely to relinquish visions, which had been held since the first World War, of the effortless and inexpensive acquisition of thousands of female volunteers.48

Revival of Plans to Draft Women

The ruinous expense of recruiting competition was now so clear that the Army, even before the end of the campaign, revived the question of drafting women, which had been rejected by the General Staff less than a year before as impossible. The Chief of Staff in early autumn personally directed Colonel Hobby to prepare a memorandum on the "selection of women for military duty." 49 This she did, noting, "A year's experience indicates the improbability of attaining, through voluntary enlistments, an adequate supply of womanpower to perform essential military services.50 The Director was now thoroughly convinced that the American public looked on the draft as the proper means of meeting military needs. To a military conference, she stated, "I believe that it is as fair to ask volunteers for service as to ask for volunteers to pay taxes . . . . When people are asked, `Why aren't you in the Service?', they remark, `Oh, come now, if the Government really needs us they will draft us.51

The plans now made were far more extensive than those that the Army had attempted in its similar legislative study during the manpower crisis of the year before. It was noted that by this time the British Government already had registered women in the 19-40 age group and had power to direct some 17,000,000 of them into the armed services or industry. The British had found it advisable to give local industrial jobs to women with domestic responsibilities, and to emphasize mobility for the armed forces; younger mobile women were withdrawn from retail trades, the clothing industry, and even the government, and replaced by the nonmobile. By this means thousands of women were being successfully called up each week. Some 91 percent of single women and 80 percent of married women of ages 18-40 were already reported to be working directly in the war effort in Britain.52

The prospects in the United States looked even more favorable. Statistics from the Bureau of the Census showed that there were an estimated 18,000,000 American women in the 18-49 age group without children under 18, of which over 5,000,000 could probably meet the WAC's high requirements and pass all tests and investigations. Of these, the Adjutant General estimated that the Army would need to draft only 631,000.53

[246]

The submitted version of legislation was therefore extremely liberal, and would have exempted all married women living with their husbands; all women with children or other dependents, women in essential industry or agriculture, nurses, physicians, public officials, and others in like category. The proposed law stated, "An obligation rests upon women as well as men . . . to render such personal service in aid of the war effort as they may be deemed best fitted to perform." 54

The Director's recommendation was that selection be scientific-by Army requirements, not numerical-since 80 percent of the jobs required skill and experience, and the other 20 percent required the ability to acquire skill with short training. Unskilled and low-grade womanpower was not wanted.

The American public seemed to be solidly behind the idea of drafting women. Gallup polls showed that 73 percent in October of 1943 and 78 percent in December believed that single women should be drafted before any more fathers were taken. Single women of draft age themselves endorsed their draft by a 75 percent majority, although stating that they would not voluntarily enlist so long as the Government did not believe the matter important enough to warrant a draft. Every section of the nation had large majorities favoring the drafting of women.55

Nevertheless, even its advocates soon realized that the plan would never be adopted unless serious military reverses occurred. Director Hobby stated in conference, " I think that what happens on the question of Selective Service depends on how long the war lasts. I do not think there is any thought of it in Congress at this time." 56

Her prediction proved correct. The General Staffs G-1 Division, after some consideration, decided that the only possible strategy was to wait until national service legislation was sponsored elsewhere and then to request that the Army be included. Some sponsorship was immediately forthcoming in the Austin-Wadsworth bill.57

Scarcely three weeks after the close of the All-States Campaign, there ensued a national manpower crisis which caused an actual "universal service" bill to be considered. In the winter of 1943-44, the Army's major training effort ended and its all-out offensive began. Overseas, the invasions of Normandy and of New Guinea were in the making. In January, the War Department announced that by the end of the year some 6,000,000 men still on training stations must be shipped overseas; station overhead was to be combed for physically fit, well-trained troops.58

The nation's manpower economy was in poor condition to support the offensive, being at the moment in possibly the most critical condition of the war. Secret and pessimistic debates in the General Council showed that Selective Service calls were not being met and that there was small prospect that more than 80 percent of future calls would be met; planners con-

[247]

sidered calling up 400,000 men previously deferred as farmers. 59 The preliminary successes in Italy in the early fall had raised civilian hopes of immediate victory to such an extent that a stampede from war industries began. War Manpower Commission Chairman McNutt denounced the workers who "seek out a safe berth in nonwar work of a permanent character." Ship deliveries declined by 40 percent; war industry noted a severe slump in production goals; and the recruiting of workers by the armed forces and defense industry redoubled in difficulty.

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson told the Senate Military Affairs Committee that "the home front is on the point of going sour," and that the morale of fighting men would be seriously affected if civilians were left free to snap up the best postwar jobs. Therefore, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox recommended that workers be frozen in their lobs in order to prevent disastrous absenteeism and turnover of personnel. The Chief of Staff publicly warned the nation that it still failed to grasp the magnitude of the effort needed for victory.60

Heeding these pleas, Congress in January turned to active consideration of the pending Austin-Wadsworth bill for "civilian selective service."61 The heads of the armed forces threw their support behind the measure as a means of equalizing the sacrifices of military and civilian personnel, warning that the war's great effort lay ahead of the nation and not behind it. From the viewpoint of the women's services, the measure appeared a sure means of ending recruiting costs and ensuring thousands of members. While the bill did not provide for the induction of women into the armed forces, it exempted enlistees from being drafted into farms and factories. British reports alleged that, under a similar act, some 40 percent of women had attempted to choose military service.62

Unhappily for such hopes, the Austin-Wadsworth bill was opposed by the American Federation of Labor-whose President, William Green, called a labor draft "servitude" and "unconstitutional"-and by the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Finally, when the Senate's Truman Committee announced its opposition, the bill was dropped. Wide-open competition for womanpower continued, under circumstances which made the manpower shortages of 1942 and 1943 appear mere preliminaries.63

No accurate estimate was ever possible as to the cost to the nation of the absence of some such law to direct women into industry or the armed forces. The Army's best estimate of the recruiting cost per Wac was $125, including advertising, recruiters' salaries, transportation, station rent, and all other expenses. This sum did not appear prohibitive when compared with the cost to the Army -$107- of recruiting a female civilian worker who might resign at any time. While no average figure was announced by civilian industry for its recruiting, the amount spent on rallies, bands, scouts, and other recruiting activities by the aircraft industry and others was undoubtedly comparable. The

[248]

Army, in return for its expenditure, had at least the assurance that its Wacs must stick to their jobs, whereas Mr. McNutt reported that in industry eight women were quitting for every ten who were recruited.64

As a result of the manpower situation, an Army directive advised all stations that they could not expect any additional military strength to replace, through the draft, the men shipped overseas. Commanders were told to replace their January losses and keep posts going as best they could by the use, in order of preference, of: (1) civilians, (2) Wacs, (3) men disqualified for overseas service, returned from overseas, over 35 years of age, or with less than twelve months of service.65

Misunderstandings at once arose over this order of listing, with Wacs and limited service men complaining that civilians were taunting them with being the less desired type of personnel. The War Department hastened to explain that the situation was just the opposite: it had been intended that the few remaining men be saved for the jobs which only men could do, the Wacs for other completely military work, and civilians used for all else. When asked by a staff officer. "Why did the War Department, in their list of replacements, list civilians first and Wacs second?" General Dalton replied, "For the simple reason that Wacs are included in the military strength and we need the military for other purposes. We are trying to use as many civilians as possible to release the military, male and female." 66 The War Department's G-1, General White, added, "We never use military personnel on a job that can be done by civilian employees if civilians can be obtained . . . . There is a serious shortage of WAC personnel. Military personnel must be used on assignments where we cannot use civilians.67

With unexpected suddenness WAC stock soared to new heights at Army commands and stations. Greatly increased requisitions for Wacs came from sources new and old. The Medical Department, which two years before had refused to employ Waacs, now stated, "With the expansion of hospitals and the withdrawal of enlisted men, there will be an urgent need for at least 50,000 additional Wacs to work in medical installations." The Chief Signal Officer asked that Wacs be increased from 9 percent to 16 percent of the military personnel under his jurisdiction, complained of the "special appeals" with which Air Forces was securing recruits, and called for "aggressive action'' to get more for the Signal Corps.

Other administrative and technical services were in a similar predicament. Director Hobby returned from a brief trip to Europe in January of 1944 with further requests from the European and Mediterranean theaters for more Wacs. At the same time a request for 10,000 Wacs was received from the Pacific theater, which had refused to employ them up to this

[249]

time. The War Department, which had previously banned the use of Wacs in the Washington area, shortly reversed the decision and gave itself first priority on the most highly skilled recruits, to the considerable annoyance of field agencies. The agency habitually the most cautious about employing Wacs, the Army Ground Forces, had only a few months earlier asked that its Wac quota be cut from 5 percent to 3 percent of the intake; in a quick reversal it now asked for a "more equitable distribution" and that its quota be raised from 3 percent to 8 percent.68

The situation prompting this sudden popularity was graphically stated to the

Air Forces by General Arnold:

If there is a man left in your organization who does not recognize that the

bulk of the men he now has working for him are going to be shipped abroad, and

that if he docs not train and use the available Wacs, civilians, and soldiers

physically unfit for combat, he will have no one to do his job-if there

is such a man; he is a definite danger to your organization.69

In the Army Service Forces, General Somervell warned his service commanders that "You must . . . give your personal attention to the eventual taking over by the Wacs of many of the jobs in your command." 70

The Chief of Staff himself went so far as to authorize release to the general public of the precedent-shattering statement that, for American women, "aside from urgent family obligations, enlistment in the military takes precedence over any other responsibility." He added, "It is important that the general public understand the Army's urgent need for women to enable the military effort to go forward according to the schedule of operations in prospect." 71

In response to the Chief of Staffs plea, the WAC was forced into its final compromise for recruiting success: the adoption of the plan labeled SJA or Station Job Assignment. At an earlier date, the Army Air Forces had proposed that its recruiters be allowed to promise recruits not only assignment to the Air Forces, but assignment to a particular station for a specified type of work-a system quite comparable to the hiring of civilian employees. Such a plan was generally admitted to be the best possible means of securing parental approval to a woman's enlistment, or of recruiting women with responsibilities that made them unwilling to leave the area of residence. The system also had the advantage of making it possible to fit the stations' needs exactly, and to recruit no skills useless to the Army; it had in fact been developed originally in the days of expansion planning as a means of preventing overrecruiting in any one skill. The job promise was also expected to attract the

[250]

skilled woman who had previously feared assignment to kitchen duties. A civilian survey revealed that 52 percent of the women questioned, although not planning to join the WAC, said that they might if they could be assured the job of their choice. Of this 52 percent, 50 percent wanted medical, radio, weather, clerical and other technical or mechanical work; only 2 percent wanted to be cooks or orderlies.72

At the time, the proposal had been rejected by Director Hobby, on the grounds that such promises were exceedingly difficult to fulfill; the promised job and even the station itself might have vanished before the recruit reported for duty. Also, such promises would plainly cause ill will among previous recruits who desired to choose another job or station.

A reversal of this decision was shortly proposed by the Army Service Forces. By the end of the All-States Campaign it was apparent that the Army Air Forces was, by means of the branch-assignment promise, getting about two thirds of the monthly take as AAF branch recruits. In addition to these branch recruits, the AAF under the War Department ruling got its original 40 percent of the general service recruits who elected no branch. A somewhat insignificant remainder was left to be divided on the customary basis of 57 percent to the ASF and 3 percent to the AGF.73

General Dalton, speaking for the ASF and AGF, demanded of Colonel Hobby why the AAF was getting more publicity. He was reminded that neither the ASF or the AGF had chosen to participate in branch recruiting when the choice was offered them the previous October, while the AAF now had some 1,500 of its personnel in the struggle. If anything, the War Department had hindered rather than helped the AAF in its publicity making, for it had forbidden the practice of saying, "Join the Air-WAC," which had occasionally caused the public to believe that a new and superior corps had been set up. The AAF was thenceforth obliged to say, " Join the WAC and Serve with the AAF,'' although the name Air-Wac was to stick as a title for the recruit herself.74

General Dalton therefore secured War Department approval for the publication of a circular giving the AGF and the ASF-but not the AAF-the authority to make the job-and-station promise to WAC recruits. An applicant's choice was limited to stations within the service command in which she applied, since before making the promise it was necessary to determine that housing and a job of the desired type existed at the chosen station. This bit of strategy gave the ASF and the AGF only a momentary advantage, since the AAF within a month secured G-1 Division's authority to make the same promise for air stations within designated air command areas.75

Station commanders now had a new and personal incentive to aid in WAC recruiting, since it was largely through their own efforts in the territory around their stations that their personnel needs might be filled. Many stations organized

[251]

part-time teams of station personnel to comb the surrounding area for recruits. General Arnold informed air bases, "The sole opportunity for station commanders to fill vacancies created by overseas shipments is to undertake active participation in Air-WAC recruiting."76

Considerable commotion and some confusion resulted as competing teams took the field. Airfield teams were especially numerous, but ports, hospitals, Signal Corps stations, and many others also participated in station-job recruiting. Posters for Air-Wacs, Port Wacs, and other varieties of Wacs offered a choice of advantages.

As expected, the administrative failure to fulfill these promises was higher than in the All-States Campaign: papers became lost; women insisted that they had been promised assignments which did not appear on their papers; Colonel Hobby's office was besieged by letters from Congressmen and parents, and was obliged to instigate endless investigations as to whether certain claims had any foundation. Some failures to comply with promises were inevitable, as the changing military situation caused certain jobs or even the: stations themselves to be closed out before recruits finished training and reported for duty, or as women proved unqualified for the jobs which they had been promised.

Another disadvantage was the schism created in the previously close ranks of the Corps. Women who were approaching eighteen months' service, and especially those who were vainly applying for transfer to a different type of work, station, or climate, or to be nearer home, were likely to look with less than sisterly affection upon recruits who had not enlisted until the job-and-station promise was made. The newcomers themselves were often ignorant of recruiting history and thus bewildered at their chilly reception by their barracks mates. Deputy Director Rice wrote all staff directors to appeal to the women's soldierliness: "I have the faith in the Corps that makes me believe that the vast majority of its personnel have learned that there is more to being a good soldier than just putting on a uniform and learning to drill and salute."77 The veteran Wacs were to have need of this soldierliness often during the remaining months of the war, as more and more attractive promises came to be offered to meet the competition for womanpower.

Because of the women's reaction, Colonel Hobby consistently refused repeated recommendations that the WAC make an even more alluring promise: that of overseas assignment. Since it remained impossible to give overseas assignments to many Wacs who had continuously sought them during months of service, she believed it unwarranted to grant these scarce plums to attract latecomers.

Results of the Job-and-Station Plan varied with the energy and the natural advantages of the station. Some Air Forces stations, particularly the more glamorous ones of the Air Transport Command, doubled and tripled their WAC population, to the limits of their available housing. Others were not so fortunate. The commanding officer of the Infantry Replacement Training Center at Camp Roberts sent a letter to each soldier saying, "If each man at this center would assist in recruiting just one woman for the WAC, there would be a sufficient number for a

[252]

STATION JOB RECRUITING DEMONSTRATIONS used in Macon, Georgia, to enlist women for duly at Cochran Field, Georgia.

[253]

complete Division." However, in the following months only two recruits were obtained and the proposed unit had to be closed out. Still other stations recruited well but not wisely; the Ground Forces replacement depot at Fort Meade found that it had selected women to do clerical work who were unskilled and untrainable for anything except car-washing. Furthermore, some stations found themselves with a group of women who needed frequent leave and holidays to manage outside responsibilities, or whose anxious parents attempted to take over company administration by telephone or in person.78

On a national scale, the returns were in direct proportion to the effort expended and to the attractiveness to the public of the various services. The Air Forces, which employed 1,500 recruiters on regular assignments plus uncounted others on part-time teams, got 5,000 of the first 5,270 branch and station job recruits; the Service Forces 250, and the Ground Forces only 20. However, the Ground Forces had assigned only one officer, a first lieutenant, to recruiting duty, and had refused his request that returned combat heroes be added to his team; such, said the AGF, would be wasteful of personnel. The Air Forces never regretted the expenditure of recruiting personnel, and stated at the end of the war that the process "secured for the AAF over 27,000 workers, many of them highly skilled and many in the prized clerical field; and it tapped a manpower reservoir that could not otherwise have been tapped, so long as women were not directed into national service by some such system as selective service.79

Final judgments of the usefulness of the station job system as a recruiting tool varied: on the one hand, it resulted in disappointments and administrative annoyances; and on the other, it continued to secure recruits, in the face of increasingly desperate competition, who could have been obtained in no other manner. For this reason, in spite of its obvious drawbacks, the system was to continue up to the closing days of recruiting, and was to be picked up in postwar Army recruiting with even more sweeping promises to male recruits, such as choice of overseas stations.

In early January of 1944, the long negotiations with the War Manpower Commission yielded the united recruiting drive that the Army had long been proposing. Labeled "Women in War," its aim was to urge women to accept some kind of fulltime war work, whether in industry or in one of the military services. The OWI estimated that there were still five and one-half million idle women eligible for such work. However, questionnaires showed that the basic restraining factor was no longer a lack of knowledge of the need but a lack of interest.

The OWI leveled all of its very considerable forces against this apathy. Newspapers, motion pictures, magazines, radio, and all other civilian news media were fully at its command, and for several weeks all devoted their plugs to the theme of Women in War-urging women impartially to join one of the armed services or to take a job in industry. Fifty national radio shows a week and countless local shows used the OWI's Fact Sheet. Stars and producers of the motion picture industry co-operated by making two-and-

[254]

a-half-minute bulletins to be attached to newsreels, and 16-millimeter films for showing in churches, schools, and war plants.

In the magazine field, 548 editors simultaneously used the womanpower theme. Through its news bureau, the OWI placed free stories with every type of newspaper: news items were given to the wire services, human-interest stories to the syndicates, and special articles to the rural. press, business press, labor, Negro. women's. and foreign-language press. Cartoonists and editorial artists at OWI's call featured an attractive Wac, Wave, nurse, or factory worker. As for posters, the nation's best artists contributed designs, while the OWI's Boy Scout Distribution Service handed out 750,000 posters bi-monthly, as well as 50,000 car cards a month. The Outdoor Advertisement Association contributed twenty-four different billboard spreads.80

All of this united activity had little perceptible effect on public apathy or on the armed forces recruitment of women: the WAC returns merely held steady at slightly below the level set by the All-States Campaign. Recruiters were inclined to believe that, had armed forces and industry earlier achieved a united front in harmonious publicity, greater results would have been obtained.

The All-States Campaign, the Station-Job Plan, and the Women-in-War drive had to some extent counteracted the slander campaign and restored recruiting to a level that permitted the Corps' continued operation. Neither they, nor any plan ever used by the naval women's services, could do more. The final lesson for the armed forces, after all the furor of effort and speculation had died, appeared to be merely the same that it had already learned in previous wars: the American public would not, without conscription, furnish the required number of volunteers for military success. In retrospect it became hard to understand why-in a nation that had been obliged to conscript men since the Civil War and in which women's service had never been popularly accepted-it had ever been imagined that women would make a better response to recruiting appeals than had men.

[255]

Page Created August 23 2002