CHAPTER XXIII

Other Overseas Theaters

In addition to being employed in the three major overseas theaters, Wacs were stationed in every other active theater of war. In each case the employment was relatively minor, never exceeding a few hundred women. Nevertheless, remaining records of the various experiments often provided clear-cut indications of the practicability of employment of womanpower in differing climates and administrative situations.

Pioneer in the employment of American Wacs in India was Vice-Adm. Lord Louis Mountbatten's Southeast Asia Command. The headquarters already employed nurses, British servicewomen, members of the Indian WAC, and local civilians, so that no great venture was undertaken when a small unit of sixty-two enlisted Wacs and four officers was added to the staff in October of 1943. After six months in New Delhi, the unit was transferred in April of 1944 to Southeast Asia Command headquarters in Ceylon, where it remained for the duration.1

Fourteen of the enlisted women were assigned to Signal Corps duties, and the remainder to routine clerical work in offices of the headquarters, both British and American. Officers, in addition to company duty, were assigned operational jobs in the same offices.

No great difficulties were encountered by the unit in the performance of its jobs. The two stations of assignment, while by no means pleasure resorts, were not the most trying in India. New Delhi, the capital, was one of India's cleaner and more healthful cities in spite of temperatures ranging up to 110° F. The Wacs nevertheless soon discovered the ailment theater veterans designated as "Delhi belly." The climate of Ceylon was tropical, without extremes of heat but with excessive humidity during the rainy seasons. Enlisted women were housed in barracks in the WRNS area, which inspectors pronounced excellent in spite of the customary bucket latrines and absence of hot water. Both men and women ate at a joint mess, which lacked cold-storage facilities and thus had only small amounts of meat and few fresh vegetables. Drinking water was boiled and stored in Lyster bags. The working day generally followed the nonstrenuous British schedule, with an 8-hour day and one day off per week.

Major Craighill, who visited the unit after Wacs had been in India for some

[463]

eighteen months, stated that "the general health of the detachment is excellent." Except for dengue fever, mild gastrointestinal conditions, and skin infections, there had been no notable illnesses, and especially no amoebic or bacillary dysentery, or malaria. One serious exception was the Signal Corps women, who were on around the-clock shifts, rotating every four days. Major Craighill noted:

A high incidence of sickness among the group working on irregular hours with the Signal Corps is significant. Of the 58 admissions for all causes, 20 were from this group of 14 women. This includes the hospitalization of ten of the fourteen: the other four have all been on sick call. These conditions are attributable to the irregularity of meals and the loss of sleep due to constantly shifting hours of work.

In spite of Major Craighill's recommendations, the headquarters did not modify the shift changes, since they were "in accordance with the present British system.2

No final recommendation was on record from the headquarters concerning the success of employment of Wacs. There appeared to be no very valid reason why women could not successfully fill many of the jobs in any such high administrative headquarters. On the other hand, there was no proof that local employees could not have done the work adequately without the importation of American women.

The intrinsic suitability of the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater for WAC employment was by no means identical with that of the Southeast Asia Command.3 Principal supply installations were in Calcutta, a city noted for oppressive heat, disease, and filth, and generally considered even more unhealthful for unacclimated white women than the more sparsely populated New Guinea islands. However, there were certain advantages not possessed by the Southwest Pacific Area, notably the fact that in Calcutta, a city approximately the size of Chicago, there were available civilian shops and tailoring facilities, as well as some approved recreational facilities. Nevertheless, the experience of nurses and Red Cross women already in the area was not encouraging; nurses had previously suffered from clothing shortages, emotional strain, tension, and a medical evacuation rate four times that of the men.4 "Wacs in India were definitely on trial," a later report stated, "as many Army officials believed that women would not be able to stand for long the climate and diseases found in Asiatic countries." 5

It was therefore not until July of 1944, two years after the Corps' establishment, that the Air Forces headquarters in Calcutta received its first Wacs. Earlier attempts to bring in Wacs had been blocked by the theater commander, Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, who eventually yielded to the Air Forces' requests only after receiving the express pledge of the Air

[464]

Forces commander, Maj. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, that any Wacs brought in by the AAF would never under any circumstances be assigned to other than Air Forces headquarters. 6

Scrupulously careful advance preparation was the keynote of the entire Air Forces project. Wacs for shipment to India were selected by the Army Air Forces from among women proved capable and emotionally stable by service at airfields in the United States. The result was so good that General Stratemeyer, upon later checking their job performance, congratulated Director Hobby, who congratulated General Arnold, who congratulated air commands in the United States, who passed the commendation on to selecting officers at airfields-the whole project ending in a glow of mutual admiration.7

This success was the more remarkable in that the theater, with typical overseas optimism, asked percentages of scarce skills never remotely approached in the United States-one fourth stenographers, one fourth typists, and the rest all highly skilled in other fields.8 It was possible to supply these satisfactorily only because the total original request was not large, less than 300. Selection was marred only by seven cases in which the routine physical inspections failed to detect serious physical disqualifications that caused the women to be returned to the United States. Much to the theater's chagrin, the first report of its WAC experiment was given to the press by one of these women, who had never set foot in India except to enter the comfortable port hospital but who was described by reporters as the heroine of a bout with jungle, heat, and disease-bearing insects, as she personally battled her way through Burma side by side with General Stilwell.9

The actual reception of the Wacs was considerably less alarming. "Never has any WAC contingent received a more cordial welcome than this group,'' wrote the WAC staff director, Maj. Betty Clague.

Everyone from the Commanding General on down has apparently had a personal interest in our welfare and happiness . . . . Everyone is impressed with the fact that they must not let down these men who have expressed such a satisfaction in having us as an integral part of their headquarters.10

Accommodations were unique, consisting of a section of a huge eight-acre jute mill, which also sheltered headquarters' offices and many of the officers' and enlisted men's quarters. Space allotment per individual was somewhat greater than that of the zone of the interior, and Wacs had not only single-decked beds with sheets and pillows, but dressers, chests of drawers, overhead fans, and mosquito nets. Latrines had toilets, showers, tubs, and mirrored washbasins. For the less than 400 enlisted women11 who eventually lived in these quarters, there were 23 Indian sweepers and about 50 ayahs, who

[465]

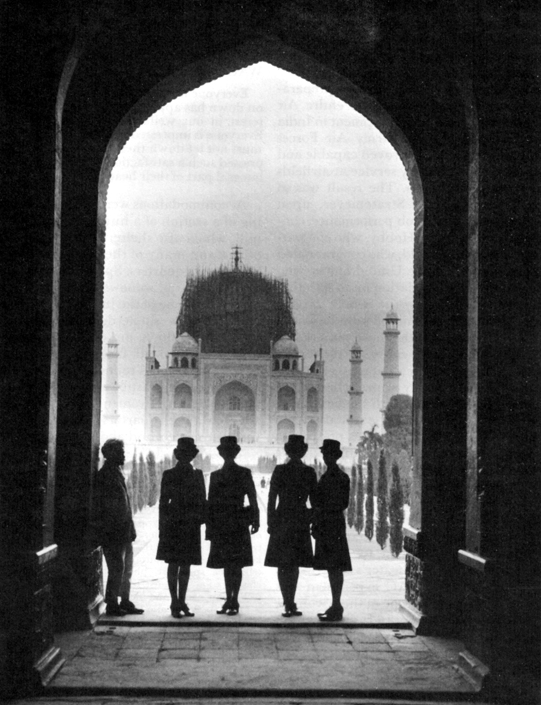

TAJ MAHAL is seen by four women of the Southeast Asia Command on a sightseeing tour.

[466]

made beds, shined shoes, washed underwear, and policed the area. There was also provided a hairdressing shop, a dispensary in the WAC area, and a dayroom with piano and radio. The only obvious objection to the arrangement was, according to medical inspectors, the noise in the big building, which made it difficult for night workers to get any sleep. In the future, living accommodations for not exceeding 75 in a group were recommended. With this exception, quarters were possibly more comfortable than the average barracks in the United States, although members expressed a mild initial surprise at observing large rats frisking through the machinery overhead, and birds roosting on the beds.12

Other advance preparations had been carefully made. The post exchange stocked needed women's items-cosmetics, stockings, brassieres, girdles, and garter belts. Wacs were admitted to the Red Cross club and to the enlisted men's club, where tea was served daily. There was a free movie theater, and free hourly bus service to Calcutta, with its Army-approved swimming pools and dining and dancing places. Provision was made for Wacs to share in the theater authorization for yearly 15-day rest leaves in mountain resorts, with breakfast in bed and sports such as golf, riding, and tennis.13

Wacs ate at the men's large consolidated mess, where supervision was taken over by an experienced NAM mess officer, Capt. Roslyn Katz, a WAC mess sergeant, and other Wacs who supervised Indian cooks and kitchen laborers. Some 8,000 meals a day were served at this mess, which was later rated as "well above the average in this theater." Food was generally considered to be as attractive and appetizing as was possible in the absence of salads, milk, fresh butter, and other uncooked items. Besides regular meals, a midnight snack of hot coffee and sandwiches was available.14

Air Forces authorities believed that they had been equally careful in making advance provision for suitable uniforms, but immediately discovered that in fact they had shown scarcely better foresight than had the Southwest Pacific Area. At the written request of the theater, each woman had been issued six off-duty dresses for office wear, since this, although not the ideal dress that could have been designed for the area, seemed the coolest garment already stocked by quartermaster depots. It was soon discovered that the dresses were "washable" only by methods seldom known to local ayahs, and "'couldn't stand beating on a rock for two or three changes a day"; even when later reserved for dress, they did not prove durable. Furthermore, although malaria control restrictions required wearing of slacks after 1800, the need for them had not been foreseen and again the only available items were herringbone twill coveralls. These, however, were pronounced totally impossible by theater authorities, since the weather was too hot to make them endurable and they "would have increased alarmingly the incidence of skin infections." 15

The theater was saved from consequences similar to those in the Southwest Pacific Area by the fact that local shops could provide the necessary items if the Wacs had the money to purchase them. The theater could find no Army funds for the issue of men's slacks, but medical offi-

[467]

cers refused to let the women leave the barracks for their evening meal until so equipped. Therefore, most enlisted women bought slacks tailored of an Indian mesh cotton. Mosquito boots were also purchased, as well as cotton anklets, sandals, and sometimes bush jackets. Also, Air Forces headquarters proved prompt in remedying deficiencies, and some months later succeeded in getting shipment for each woman of five cotton skirts and seven short-sleeved shirts for office wear, as well as three pairs of women's khaki slacks for wear after 1800. For the two or three colder months, wool clothing was provided. Eventually, CBI Wacs, by their own and theater efforts, had about double the amount provided for Wacs in semitropical climates in the United States, although no more than medical authorities deemed necessary in view of the frequent changes of perspiration-soaked garments that were required to prevent illness.16

All of the provisions of Air Forces headquarters for its men and women, although frequently exceeding the average for military facilities elsewhere, paid off in respect to the health rate. At the time of Major Craighill's inspection in March of 1945, no Wacs had been evacuated to the United States for medical reasons, except the original seven; who had disqualifying defects upon arrival. If these were counted, the loss rate was still only about 2 percent per year as compared with 2.1 percent for the theater.17

Major Craighill reported, "The medical care and condition of women is in general, good. They seem to stand the strain of overseas service as well as do men.18 Both WAC and theater authorities attributed the low loss rate to the fact that Wacs were not only encouraged but ordered to report to the sick bay in their barracks at the slightest sign of any disorder, or even for advice. As a result, as many as 10 percent of the women in winter months, and 20 percent in summer, reported each month to the sick bay for cases not requiring hospitalization, as against 5 and 9 percent, respectively, for men. Theater authorities urged women to patronize medical facilities even more frequently if necessary, and provided not only a nurse for the well-equipped dispensary, but a gynecologist in the local hospital.

There was every indication that, without such constant care, the health hazards of the area would have been comparable to those of the Southwest Pacific Area, for illnesses included both amoebic and bacillary dysentery, impetigo, hepatitis, various fevers, and respiratory disorders. Major Craighill recommended that two years' service in the area be the limit, since "Among nurses who have been overseas two years or more, there is an obvious increase in tension, manifested by irritability, depression, insomnia, and loss of effective energy.19

An additional health problem was what Major Craighill called the "great emotional strain" from the social demands of "a group of isolated and lonesome men." While Wacs were by no means the only white women in the theater, they were nevertheless overwhelmed upon arrival with such numerous offers of social engagements that not all could be accepted. In the interests of health and working efficiency, WAC commanders from time to time prescribed dateless nights, quiet

[468]

hours, and other expedients. After the first months, most Wacs were fatigued by the constant masculine attention, and found organized parties and mass invitations especially tiring.20

Coupled with the theater's precautions concerning health were, in the early days, numerous protective restrictions which, although not comparable to those in the Southwest Pacific Area, the Wacs found annoying. Wacs could not participate in airplane flights, had bed check even though men did not, could not accept overnight invitations from local families, could not spend the night away from their quarters even in approved service centers, could not date officers, and could not marry.21 These restrictions caused a certain number of Wacs to inform the chaplain that they were being "treated as children.22

Most of these restrictions were therefore quickly abolished as initial misgivings concerning the employment of Wacs subsided. Although bed check was retained as a health safeguard, hours were usually lenient, and Wacs were eventually allowed to stay overnight at the women's service center. Wacs were also soon allowed in aircraft, and at least one technician was placed on regular flying duty for which she received the Legion of Merit and the Air Medal.23 The restriction on dating officers was not removed until Wacs reached Shanghai, and some difficulty was caused by the fact that Air Forces Wacs were liable to punishment while officers of theater headquarters, which had no such rule, were immune.24

The restriction on marriage, a theater ruling, was the most objectionable to the women. The rule had been designed to prevent the marriage of soldiers to noncitizens, and had been modified just before the Wacs' arrival to permit marriage only if a soldier was leaving the theater within thirty days. Cases involving pregnancy were considered individually on their merits. At the time of Major Craighill's visit, Wacs still had a pregnancy rate of zero, but WAC commanders considered the system, for obvious reasons, incredibly shortsighted. In April of 1945, after receipt of Major Craighill's recommendations, and after the first Wac achieved marriage by the only theater-approved method, Lt. Gen. Daniel I. Sultan liberalized the policy to permit marriages between two United States citizens after a three-month waiting period. With this one case, the WAC pregnancy rate was only one fourth of one percent, or considerably less than the average. No cases of venereal disease were discovered among any WAC personnel.25

As always, factors of physical surroundings proved less important to the women than that of job satisfaction. Initial job assignment was far from perfect, a condition that General Stratemeyer attributed chiefly to "a failure on the part of officers

[469]

to appreciate capabilities, and overstaffing during the period of orientation prior to the transfer of enlisted men replaced by Wacs.26 General Stratemeyer took immediate and vigorous action to correct the situation.27 As a result, the expected 30day on-the-job training was reduced to 15 days.

A few months later General Stratemeyer directed his WAC staff director to make a survey of job utilization. It was found that, "with a very few exceptions, the qualifications of Wacs were being fully employed in jobs commensurate with their training and experience," and the exceptions were at once corrected. Some problems still remained. The offices were not exceptionally busy, at least not enough to satisfy the Wacs. Also, civilian competition was present from female citizens of Calcutta. The staff director remarked:

I believe that the biggest hindrance toward the proper utilization of WAC personnel in this Headquarters is the usage of inefficient civilian help. Because of their employment in the majority of stenographic positions, the Wac is compelled to watch someone else do a job which would ordinarily take her one-half of the time to complete.

Because of the constant attention to the matter of correct assignment, however, lack of work never became a morale problem. An Army observer confirmed this assertion about Wacs' high morale and its cause, stating that:

The women look well, work efficiently, are universally cheerful and seem almost without exception to feel that they are doing an important war job . . . . The WAC personnel are universally admired and respected by male officers and enlisted men here. They have made a definite contribution to the morale of the base and the efficiency of the headquarters here, and I believe that their excellent attitude reflects their pride in this fact.28

General Stratemeyer, at the time of the separation of the China theater from the India-Burma, reported to Generals Stilwell and Arnold:

Experience of the past several months has proved any doubts concerning the propriety of the experiment to be false. It is with enthusiasm that this Headquarters reports the substantial overall improvement in efficiency as a result of the placement of Wacs . . . . Officers and enlisted women alike have quickly adjusted themselves to the climate, food, and the somewhat rugged living conditions .... Deportment is superior. Not one untoward incident has occurred as a result of their presence in this Headquarters . . . . This Headquarters recommends without hesitation to other Headquarters overseas the excellent benefits to be obtained through the placement of Wacs in theaters of operations.29

The newly organized Services of Supply headquarters in Kunming, China, immediately petitioned the commander of the U.S. forces in the China theater, Lt. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, for permission to bring in a WAC company almost identical with the Air Forces' company, saying:

It is virtually impossible to obtain competent civilian clerical employees in this theater .... Male enlisted personnel trained in typing and stenographic duties are not available in sufficient numbers .... Where the civilian employee is not a citizen of the United States, as is almost invariably the case in this theater, effective security is largely unknown.30

[470]

However; theater headquarters refused this: "The decision of the Theater Commander is that no Wacs will be brought into the China Theater for the present." Six months later, the SOS asked again and was again refused on the grounds that "we cannot quarter these people . . . including mess, toilet, and living space. 31

There was also some objection to the Air Forces' proposal to take Wacs to China when its headquarters moved to Chungking in July of 1945, but because of General Stratemeyer's insistence, the objection was overcome. It was known that living conditions would be far less favorable than in India, but two hundred of the Wacs volunteered to go and about a hundred were chosen, this being all that the reduced headquarters could employ. Again, preparation was careful. Maj. Beryl Simpson, who had replaced Major Clague as staff director, visited the new site to check on all accommodations before the order was given to send the enlisted women. The first WAC contingent flew the Hump on 3 August 1945, closely followed by others.32

As expected, living conditions in Chungking were less settled than in India.33 With much work and close sanitary supervision of native help, an attractive mess hall was maintained, and within three days the Wacs had set up their own laundry and trained local help to give good personal service. The hundred women eventually employed some sixty Chinese servants for mess, laundry, and yard work. Housed in dormitories similar to the civilian women's, Wacs eventually obtained a few fans, an improved water supply, and better electric lights. In spite of predictions, the headquarters reported that a "low rate of sickness" prevailed among Wacs, and that "the sweltering heat failed to impair efficiency." As in India, Wacs were urged to seek medical advice frequently. Records showed that in six weeks over half of the women had been on sick call, although much of the rate resulted from the fact that almost all members were getting daily treatments for prickly heat, an annoying but nonfatal malady, which caused little loss of work time.34

In accordance with General Wedemeyer's policies, the headquarters was careful to allow no appearance of favoritism to women, who were trucked to work as were men, issued supplies in the same manner, and generally treated as other troops. In this respect, the move to China accomplished several goals that the WAC staff director had never been able to attain in India. The extreme friendliness of the Air Forces headquarters in India had always been such that WAC staff directors and unit officers were occasionally hard put to maintain strict discipline and military appearance. Before the Wacs arrived, nurses had been allowed to wear civilian evening dress in spite of Army Regulations and rules on malarial control, and it did not prove easy to convince the headquarters that the WAC was best treated as a fully military organization.35

[471]

Late in 1944 the staff director discovered a move by junior WAC officers to override the regulations on conduct and uniform by securing from senior Army officers contradictory statements, which were "usually made in a spirit of conversation at mixed parties." 36 These attempted violations the staff director was able to quash, but there remained the problem that Army officers were often "accessible and sympathetic to personal requests." 37

Some months later the staff director reported that "a good many enlisted women are relaxing their efforts with regard to their personal appearance and individual conduct." She also called the women's attention to the fact that some Wacs were not "promptly and properly rendering the salute." Detachment regulations thereupon required that hair must be neater; T shirts invisible, shirt sleeves up or down but not halfway; no flowers or "other articles of non-military nature" could be worn in the hair; short or tight skirts must be let down or out. "It is essential," the staff director informed the women. "that the reputation thus far enjoyed by all members be maintained, that no relaxation be permitted that might adversely affect the generally accepted idea that American women soldiers are well dressed, personable, and conduct themselves as ladies."38

A few weeks after the stricter detachment regulations had been published, they were partially canceled by General Stratemeyer, who, on a visit to the Southwest Pacific Area, had noted that General MacArthur's Wacs and General Kenney's Wacs "were wearing decorations such as flowers and ribbons in their hair during working hours." Being ignorant of the fact that General MacArthur's Wacs by this date had nothing resembling a military uniform, General Stratemeyer was favorably impressed. Over the staff director's protests, new official uniform regulations contained the provision-probably unique in the history of the Army-that "Flowers or ribbons are authorized and encouraged for wear in the hair." 39 The staff director conceded defeat, with the notation:

There is absolutely nothing General Stratemeyer would not do for his Wacs to make them happier . . . we will therefore accede to his wises; though they are contrary to the military indoctrination we received . . . .40

The move to China, combined with the location of the Air Forces headquarters in the same compound with General Wedemeyer's headquarters, caused considerable change in policies in this regard. Corrective action was first undertaken informally by a memorandum:

General Stratemeyer this morning expressed a personal hope that all his Wacs would be so prompt and snappy in their saluting that General Wedemeyer would voluntarily say to him, "Boy! Are those Wacs good!" He pointed out that sometimes we get so interested in the conversation that we fail to notice an officer, and often that very officer is Just the type to report the failure to General Wedemeyer. 41

This document having had all the effect that might have been expected, a month

[472]

later General Stratemeyer noted, "Saluting by enlisted women was still extremely lax." He therefore issued more unmistakable orders that "the situation be corrected at once." At this the staff director, expressing considerable pleasure, showed great alacrity in informing the women that they would be court-martialed in a most military manner if that was the only way to get them to salute and to wear hats on the street.42

Happily for all concerned, the women reverted to their military training without noticeable loss of efficiency or morale, and impressed General Wedemeyer sufficiently to cause him to request General Stratemeyer to contribute Wacs to theater headquarters. At the close of the stay in Chungking. General Stratemeyer informed the women:

You have . . . established an enviable record of efficiency which has immeasurably facilitated the accomplishment of the mission of my command . . . . Your performance stands as a worthy goal for any military unit in the Armed Forces of the United States.43

With the defeat of Japan, the headquarters moved to Shanghai, taking the Wacs with it. With the approaching inactivation of the Air Forces headquarters, General Wedemeyer's headquarters took over all of the women, including the staff director. He later requisitioned and obtained double their number direct from the United States.

Even in the postwar wave of demobilization fever, less than half of the Wacs eligible for discharge desired it, and the headquarters strongly urged them to stay.44 In Shanghai, the Wacs were visited by the new W:'1C Director, Colonel Boyce, who had intended to direct their return to the United States, as had been necessary in the Pacific. Upon seeing the women, Colonel Boyce changed her mind, pronouncing them a carefully picked, seasoned group, all volunteers, who felt that their services were needed by the headquarters, and whose morale was correspondingly high. Most had by this time worked their way into key positions, and many were section chiefs, so that the headquarters was reluctant to part with them. The women themselves stated that they were willing to remain either as Wacs or as civilian workers. As a result, Colonel Boyce agreed to leave them indefinitely and to support General Wedemeyer's requisition for more.45

The China theater Wacs later moved from Shanghai to Nanking and Peiping; the group in Peiping staffed General Marshall's mission to China until its return. In both cities, the staff director noted that "their living arrangements and job assignments were as carefully prepared in advance as was their original entry into China." As the American forces quit China, some women moved to Japan and others returned to the United States.46

The employment of Wacs in India and China, although on a small scale, had done much to counteract the impression that women could not be successfully cm-

[473]

ployed in a tropical or disease-ridden area. The low medical evacuation rate, and the willingness of the women to remain for indefinite periods, both indicated that they were adaptable to such employment. However, all WAC advisers noted, in conclusion, that such success was likely to occur only in headquarters that made careful advance preparation and maintained a constant friendly alertness to detect developing problems.

An example of the use of Wacs in an inactive theater was furnished, on a small scale, in the Middle East theater.47 Here were assigned two WAC companies, totaling slightly less than three hundred members-one located in the city of Cairo, the other several miles outside it at Camp Russell B. Huckstep.

The first request for Wacs in Cairo was received in the fall of 1943 from Maj. Gen. Ralph Royce. General Royce at this time asked only for twelve WAC secretaries "to prevent the constant and sometimes serious leaks in information." 48

The request was approved, and in December of 1943 ten enlisted women and two WAC officers were flown to the area. Capt. Josephine Dyer headed the group and later served as staff director. Other requests followed: one for 240 women for theater headquarters, which was approved; one for 600 women for Tehran, which was disapproved on the grounds of nonavailability of WAC personnel; and two others, of 150 more Wacs for theater headquarters and 104 for the 19th Weather Squadron, which were disapproved by Operations Division of the War Department on the grounds that no military vacancies existed in the command. Before making these requisitions, the theater had entertained some hopes of on-the-spot enlistment of American women living in Cairo, but it was found that 49 out of 50 eligible civilian women refused to enlist, and the idea of local recruiting was abandoned as it had been in Europe.49

The shipment of 240 women for the Cairo area was accordingly organized in the United States in February of 1944. It reached the theater only after an exhausting four-month struggle to get shipping space, during which the unit spent a month at Fort Oglethorpe, a month in one area at Camp Shanks, three weeks in another area, a week at Camp Patrick Henry, three weeks on shipboard, and ten days in Naples. The delay proved trying for the women, who were so eager to get overseas that 118 of them, 13 in the first three grades, voluntarily relinquished their ratings in order to comply with the theater's requisition for unrated personnel. The women were described as "dejected and disillusioned" during the months of waiting, but their morale rose rapidly as soon as they were in transit. 50

Arriving in Cairo on 16 June 1944, the women were sent to Camp Huckstep,

[474]

where living conditions were pronounced by detachment officers to be "far superior to any experienced by the unit since its inception." The brick-and-wood barracks were clean, modern, and airy, and latrines were in the same building. There was plenty of hot water, and a laundry with ironing boards and washing machines. In this the women's barracks were superior to those of some of the men's units, which did not all at this time have hot water. Barracks had single-decked beds, pillows, bedding, and shelves and hangers for clothing; there was also a well-furnished dayroom with recreation equipment. On the whole, the accommodations were described as being "in striking and overwhelming contrast to the haphazard facilities encountered in the United States." The only difficulty was a temporary one when, on the first morning, it was announced that Maj. Gen. Benjamin L. Giles was to review the Wacs immediately, and 240 travel-wrinkled women descended simultaneously on ten electric irons.51

Within a week, 126 of the women moved to Cairo for duty with Headquarters, Africa-Middle East Theater; the remaining 114 at Camp Huckstep were assigned to the Middle East Service Command. The unit in Cairo was billeted in the New Hotel, two to five women to a room. At the end of the year, after winter rains had flooded parts of the building, and after the arrival of more Wacs left it overcrowded, the Wacs moved to new quarters in a modern building with a bedroom for every three women and a complete post exchange and hairdressing shop.52

As the women were interviewed and assigned to duty, a fundamental problem emerged: the theater was already at full authorized strength and not in desperate need of personnel. If Wacs replaced enlisted men, the men were idle, and if Wacs were merely added as supernumeraries, there was only part-time work for all concerned. The majority of the women were stenographers, clerks, and typists; others were messengers, bookkeepers, telephone operators, and teletypists. Many were assigned as secretaries to ranking officers, and others were placed in almost every staff section of the two headquarters, with the largest numbers in the adjutant general's office, the Signal Corps, and the Censorship Section.53

While most women were well satisfied with the type of work assigned them, the fact that it was not full-time caused a continuing morale problem among both men and women. At Camp Huckstep, the WAC historian reported:

Morale was affected by the existent morale at Camp Huckstep ; which was poor and contagious. The majority of the men, and consequently of the women, felt that they were not actually needed and that what they were doing was not important to the war effort. Wacs were resented by some of the men.54

Promotions could not be given to any of the Wacs, even to a few who had replaced master sergeants, so long as the command remained overstrength. The Cairo report added:

Comfortable living quarters and opportunities for enjoyment seem to be secondary in building morale . . . the important factor is the feeling that they are needed and that individual assignments keep them busy.55

[475]

During the first summer, only 56 of the 240 Wacs replaced enlisted men. Toward the end of this time, the theater appealed to the War Department for authority to return the surplus men to the United States. By October, enough men had been removed from the theater so that 157 promotions were made among the Wacs, chiefly to the grades of private first class and corporal. These were followed by others at intervals. By the following spring the Cairo detachment reported:

The morale for the past period has improved . . . due partly to the fact that most of the women are now fairly busy, and also to the fact that they have a feeling of being generally accepted as a part of Headquarters.56

The theater consistently directed its efforts toward devices to maintain troop morale, and in these the Wacs were allowed to share fully. At Camp Huckstep, women were admitted to the excellent recreational facilities-a theater, a service club with cafeteria, game room, and library, and sports equipment. In Cairo, women were allowed to join a club with swimming, tennis, and golf facilities. At both stations, Wacs shared athletic programs in league baseball, volleyball, hockey, basketball, and even touch football, although such programs appealed only to the younger women. Women were also admitted to off-duty classes offered by the Armed Forces Institute in such subjects as French, Arabic, shorthand, and photography. Social activities were also encouraged, with organized parties and holiday celebrations, but the Wacs reported that such activities soon became burdensome and most women declined unit invitations.57

Wacs likewise were given the same amount of leaves and passes as the men, and were provided with equal transportation and accommodations to visit various points of interest for sightseeing or recreation. There were frequent conducted tours of the environs of Cairo, and visits by some of the women to Bengasi, Alexandria, Cyprus, Palestine, and other areas.

Restrictions were seldom sufficient to cause complaint. Marriages were permitted, suitable married quarters were provided, and women were allowed and even encouraged to spend furloughs with husbands stationed elsewhere. Nevertheless, WAC marriages in the theater were not frequent.58

Considering the climate and the sanitary hazards of the surrounding cities, the women's health remained good. A sanitary mess was maintained, and the nature of the area caused only minor discomforts. During the winter a water shortage was suffered, and cold weather made the unheated buildings chilly, but kerosene stoves were soon obtained and men's pile jackets were issued to the women. Heavy winter rains found a small Nile coursing through the WAC barracks; the boiler broke down; a high wind blew down the reed blind fence around the WAC area and the improved view was enjoyed by both women and men until the fence was put back up. None of these minor environmental difficulties had any appreciable effect on morale or health.

Major Craighill, who visited the area late in December of 1944, found the women's health good and illnesses "relatively less than in other units in the area."

[476]

In the Cairo unit, women suffered the usual respiratory and gastrointestinal conditions, but in less degree than the men, and there had been no cases of venereal disease, pregnancy, malaria, or the hepatitis that was prevalent in the area. Emotional maladjustments had been minor, only one case requiring return to the United States.

Camp Huckstep Wacs had likewise had no unusual medical conditions except an incidence of appendectomies to a total of almost 10 percent of the group. There had been no cases of venereal disease, and only one pregnancy, which had existed before arrival in the theater. However, Camp Huckstep Wacs had experienced a number of minor maladjustment problems and two serious psychiatric cases, one of which had to be sent back to the United States. These cases were not more numerous than similar cases among men and, according to Major Craighill, "were reflections of the enlisted men's attitude of frustration in an area removed from the combat zone." Improvement in this respect was noted when surplus personnel was shipped out. Gynecological conditions were minor and caused no loss of time from work or any evacuation of personnel from the area.59

The only policy problem noted by historians was a minor version of the Pacific and European theaters' major problem: the question of direct commissions for enlisted women who were secretaries to ranking general officers. As soon as the news of such commissions elsewhere reached the theater, General Royce repeatedly applied to the War Department for permission to commission his secretary. The request, with others like it, was refused upon the insistence of Director Hobby, who had secured a ruling against any further such action as a result of the bad publicity accompanying earlier cases. The Director suggested instead that the woman, if qualified, be selected by regular board procedure and returned to officer candidate school with promise of return to the area upon graduation. General Royce instead preferred to appoint the secretary a warrant officer, which he did. No further comment resulted except sharp newspaper criticism of the commanding general's wisdom in using public funds to make his personal plane available to the secretary and her husband for an extended honeymoon tour of the Mediterranean. 60

As the end of the war neared, restlessness increased, and both men and women were heard commenting that they wished they were in Italy. France, America, or almost any other place. Luckily the waiting period was not long, and soon after V-J Day shipment began, with the last Wacs returning home in October 1945. Colonel Boyce, who stopped in Cairo shortly afterward on her way home from India, interviewed the chief of staff and stated that "The Wacs were highly commended for their work and they were released only when there was no longer a job to be done." 61

Although recommending a two-year limit on the tour of duty, Major Craighill stated that the theater's experience with the employment of Wacs and nurses had

[477]

proved that "women can adjust satisfactorily to difficult environmental problems under proper administrative control." Other authorities concurred, with the additional comment that employment in an inactive theater would possibly always present problems of full-time employment and therefore of morale.

At various times requisitions and inquiries were received from other overseas areas, all of which were disapproved or withdrawn. In general, refusals were due to a desire to reserve the WAC's services for more active theaters, or to the fact that civilian help was plentiful in the areas concerned.

Hawaiian Department

A tentative requisition from the Hawaiian Department was received in late 1942 for one or more WAAC companies, and was favorably considered by WAAC Headquarters. 62 However, further investigation revealed that Waacs were chiefly wanted to replace civilian women in the Aircraft Warning Service. With the decision to count Waacs against the Troop Basis, such requisitions were automatically eliminated. No Wacs served in Hawaii except those with the Air Transport Command, which employed them in military duties.

Canada and Alaska

Requisitions were received in 1943 for about 700 women for stations in Canada and Alaska, including Edmonton, Whitehorse, and Dawson Creek. These were refused, not by the WAC, but by OPD and by ASF's Military Personnel Division. At a later date, and after arctic clothing for women was standardized, Air Transport Command Wacs served in both areas without reference to the War Department for approval .63

New Caledonia

Inquiries were received from New Caledonia in 1943 concerning the possibilities of getting some 40 WAC telephone operators and an unspecified number of other workers. Both were disapproved by OPD, for the stated reason of shortage of WAC personnel. A few WAC officers were later stationed in the area for varying periods.64

Puerto Rico

When the WAAC was organized, the Antilles Department rejected the idea of employing its members, as a large Puerto Rican labor supply was already available, and housing would present problems. Therefore, for the rest of World War II, Wacs were not requisitioned or employed. In April of 1944, the Antilles Department recommended that a WAC recruiting party be sent to Puerto Rico, inasmuch as the WAVES had already been there. The War Department accordingly sent one WAC officer and three enlisted women, authorized to recruit not more than 200 women for service in the United States. There was an enthusiastic response-some 1,500 immediate applications-but many had to be rejected for failure to pass the aptitude test, or because of parental ob-

[478]

jections. Also, later employment was handicapped by language difficulties.65

In addition to overseas personnel under the command of the various theaters, there were several thousand overseas Wacs who were not assigned to any theater but to the numerous independent commands authorized to send part of their personnel overseas. Neither the allotment nor the command of such personnel was a prerogative of the theater, but remained with the parent organization. Such commands included various War Department boards and groups, the Office of Strategic Services, the AAF Weather Wing and Army Airways Communications System, and especially the Air Transport Command. Most such commands seldom employed more than five to ten women at any one station, and ordinarily attached them to the nearest WAC unit for housing.

Just as in the United States, unit problems and schisms frequently resulted from the presence of these privileged outsiders with different schedules, rules, ratings, and status in general. No particular solution was reported by the theaters, other than to suggest that full disciplinary control was essential to the unit commander. As a result, theaters did not encourage most independent commands to more widespread employment of women.66

Of the independent commands, the ATC was by far the largest, employing Wacs in such numbers as to make possible establishment of its own detachments to a total of some 1,300 women overseas. By special War Department authorization, ATC was empowered to determine suitable overseas stations, and select, stage, and ship WAC personnel without reference to Air Forces headquarters or to the War Department. By the end of the war it had some 241 Wacs in Alaska, 236 at two stations in Africa, 460 at five stations in the European theater, 156 in Labrador, and 227 in the Pacific.67

On the whole, the results of assigning Wacs overseas in such independent and often unsupervised situations compared unfavorably with the experiences of those under theater jurisdiction. While efficiency seldom was affected, morale, conduct, and the full utilization of skills suffered. Theater experiences had, with one exception, indicated that Wacs overseas were uniformly successful and presented few problems, but the example of the independent commands, as well as of the North African theater before the arrival of its staff director, strongly suggested that such success was by no means as inevitable as its universality suggested, but instead depended to some extent on close and careful selection and supervision.68

[479]

Page Created August 23 2002