CHAPTER XXVI

Housing, Food, and Clothing

It was the Army's policy that "standards for housing of the WAC approximate the standards for housing of male personnel, varying only where the differences between men and women necessitate changes and adjustments.1 The modifications deemed necessary to convert Army barracks for female use were in general of two types: those essential to safety and segregation from men, and those required to adapt the plumbing and similar facilities.

For proper segregation, it was required that WAC barracks be at least 150 feet from men's barracks, or with an intervening structure: in no case were women to be housed in barracks in the midst of enlisted men's barracks. Wacs were also to be allowed window shades, where necessary, for privacy. The WAC latrine was required to be inside, or attached to, the WAC barracks, for safety as well as for privacy. For the same reasons, and to permit walking to work, it was suggested that WAC housing be in the station-complement or headquarters area, never with field troops.2

Modifications in the plumbing included not only the elimination of certain fixtures, but the provision of others believed needed for feminine hygiene, such as two bathtubs per 150 women. British experience pointed to the advisability of partitions or curtains between showers and toilets. Sheets were authorized for the beds in the barracks, after The Surgeon General expressed the opinion that sanitation problems peculiar to women would make it easier to launder sheets than blankets.3 For laundry one tub and ironing board were allowed for each twenty women, plus drying racks for garments. Enlisted women ordinarily provided their own irons.4

Experiences of the first year gradually dictated a few more modifications. It was found that women in the WAC service uniform, with its narrow skirts, had difficulty in jumping from windows to the standard fire escape ladders, and fire stairs were ordered substituted on two-story barracks. After several women received severe shocks from using electric irons while standing on wet concrete floors in laundry rooms, duckboards were authorized beneath ironing boards.

It was found that the Army-type mess hall tables with benches attached were unsuitable for individuals in skirts because of the difficulty in climbing over the

[515]

bench; it was therefore directed that the benches in WAAC mess halls not be attached to the table, or that stools be substituted.

Also, since most women carried their personal belongings in ordinary luggage rather than in barracks bags when on leave or individual travel, two square feet of luggage storage space per enlisted woman was authorized, provided that no great cost was involved. Such space was usually available, since women's units required only 330 square feet for company supply as against 1.037 for men's supply and combat equipment.5

Decline in Housing Standards

With the exception of these improvements, all later modifications in housing made during the first years were in the nature of successive compromises with expediency, involving gradual reduction of standards. Except at Fort Des Moines, no training center housing conformed to standard. Most schools were occupied hastily and for a short time only, and had outside latrines, uncurtained showers and toilets, and sometimes men's plumbing fixtures. Port and transit facilities were of course never modified for women. The earliest WAAC barracks on Army posts in general were constructed according to specification, but when Waacs began to count against the 'troop Basis, new construction became the exception rather than the rule, being authorized only where it was impossible to convert the barracks of the men who had been replaced.6

At the same time, standards for Army construction were falling rapidly as the supply of materials became more critical. Construction at Army camps had long since ceased to be of a permanent type. The "mobilization-type" construction, which was at first substituted, permitted a fairly substantial frame building, usually with central heating. WAAC Headquarters immediately agreed to the Chief of Engineers' plan for mobilization-type instead of permanent housing for Waacs, except for his proposal to eliminate the two bathtubs formerly installed in new construction. Supporting WAAC Headquarters' view, The Surgeon General again stated that tubs were necessary for feminine personal hygiene, but Requirements Division, Army Service Forces, refused to permit further installation of bathtubs, and later barracks had none.

WAAC Headquarters also agreed, in the interests of economy, to abandon the earlier plan for housing a company in three one-story barracks for fifty women each, in favor of a new plan for two two-story barracks of seventy-five each. This plan, while saving one building, required the women's beds to be double-decked and crowded closely together, with less space for wall and foot lockers. This type of construction was used for many of the Air Forces WAC barracks and for some in other commands.7

As the war continued, the mobiliza-

[516]

tion-type housing was succeeded on many stations by the highly temporary "theater of-operations- type," warmed only by coal stoves and easily penetrated by heat or chill. Here a soldier's allotted home was frequently an upper bunk so near the ceiling that he could not sit up, plus a coat rack and shelf for personal possessions, in a barracks stiflingly hot in summer and drafty in winter, with coal dust sifting over the sleepers.

Colonel Tasker, at that time in charge of WAAC housing, protested to the Army Service Forces that theater-of-operations type housing was intended only for temporary emergency use by transient trainees and that "permanent or semipermanent housing facilities provided for units of the WAAC are not considered emergency [housing].8

Nevertheless, Requirements Division directed the WAAC to use theater-of-operations-type housing, which cost only $8,720 per unit as against $13,300 for the sturdier mobilization type. A 74-man barracks was used for 81 women, or a 63-man building for 74 women, which gave each woman a space allowance of 50 square square feet as against the previous 60 for men. The Chief of Engineers soon informed the Director that the 50 square feet was a miscalculation, and that only 42.5 per woman could be allowed in converted buildings, or 45 in new ones. Although WAAC Headquarters entertained considerable doubts of the wisdom of the decision, Director Hobby felt unable to object, and informed staff directors, "We will have to compromise. We cannot use critical material for construction of new barracks." 9

By the end of 1943, reports brought in by General Faith's Field Inspection Service and other agencies indicated that the current policy was a miscalculation of the actual need in two directions. Wherever the employment of WAC units paralleled the employment of Army units, almost no modification proved really essential. Most Army units were merely in training for a relatively brief time at various posts in the United States, preparatory to overseas shipment. Even in station-complement units an able-bodied man was virtually certain of overseas shipment within a year or eighteen months. Wherever women were similarly treated-brief periods at various training schools, staging areas, ports, and in overseas theaters-they proved able to sleep in crowded double-decker barracks, use communal showers and outside latrines, or live in tents, hutments, trailers, or any other emergency form of housing, without special modification for women.

Unfortunately, since 85 percent of the WAC never got overseas, in the great majority of cases the experience of a WAC unit was not at all comparable to that of Army units. Women, after a brief training course, found themselves at the station at which they were to remain for several years. Under the circumstances, their needs for housing resembled those of the peacetime rather than the wartime Army.10

British inspectors had come to an identical conclusion:

[517]

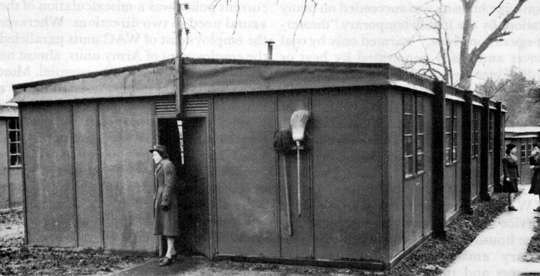

WAC HOUSING. Exterior, above, and interior, below, of two types of quarters furnished women at an air base in England.

[518]

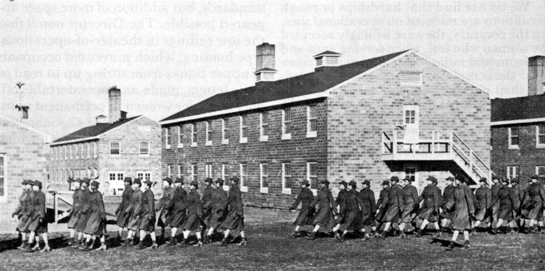

WAC HOUSING. Brick barracks at Fort Des Moines, above; below, interior of mobilization type construction with central heating.

[519]

We do not find that hardships or rough conditions are resented on operational sites: on the contrary, they are willingly accepted by women who feel, when serving guns and balloons and radio-location, that they come near the actual war and that they are playing their part in the struggle. It is the boredom of non-operational units in old-fashioned barracks or uncomfortable quarters which is a more potent source of discontent than real hardship . . . . Grumbling does not arise over temporary conditions, however hard, which the girls instinctively feel are part and parcel of the war.11

The Navy, recognizing the permanent nature of WAVES employment, provided two- and four-woman rooms similar to the dormitories of civilian women workers. The Bureau of Naval Personnel stated:

Adequate housing was an especially urgent problem for the Women's Reserve in view of the relative permanence of the women's assignment to a station, compared to the men. . . Housing for women called for certain features not provided in men's barracks: ironing boards, lounges, and the semiprivacy of a four-person cubicle (because women spend more time in quarters than men), more stowage space (the women's uniforms called for more space if they were to be kept in good appearance), more laundry facilities. These features were called for not as special factors or coddling but because they made the women more efficient members of the organization.12

For the WAC, it appeared that something resembling the peacetime Army barracks would be adequate for permanent units, although division into cubicles also appeared advantageous in a nonhomogeneous unit where members were on different shifts and schedules.

As early as the summer of 1943, the Director therefore held numerous conferences with representatives of The Surgeon General, Requirements Division, ASF, and the Chief of Engineers. For housing already built, it was too late to change the standards, but addition of more space appeared possible. The Director noted that the low ceilings in theater-of-operations type housing, which prevented occupants of upper bunks from sitting up to read or write letters, made an uncomfortable off duty home for women in permanent units. She therefore asked that the 42 square feet per individual be increased to 60, which would remove the need for double-decked bunks and permit more space for clothing. 13

The Army Service Forces concurred in this request, but virtually nullified it by stating that the provision would not be retroactive. Since housing for 98,000 women had already been built, there was to be little new construction to benefit by the improved standards. After another six months, the commanding generals of the Air Forces and Ground Forces and the Chief of Engineers supported the retroactivity clause, and eventually secured the concurrence of the Service Forces.14

This decision marked the limit of wartime changes in WAC quarters. Nothing could be done about the flimsy theater-of operations-type housing for permanent units, concerning which poor reports continued to come in. Near the end of the war, WAC inspectors found that six out of six general hospital WAC detachments visited had this type of barracks, heated only by "space heaters." In no case, inspectors reported, was this the desire of the hospitals, which felt that the maintenance cost was higher than that of central heating, in spite of the lower initial cost. Wards also lost in efficiency when obliged to relieve women from their regular duties

[520]

in order that they might stoke the: coal stoves. In one hospital, use of poor-grade coal caused hospitalization of a large part of the detachment for carbon monoxide gas poisoning. An Army Air Forces study likewise concluded that theater-of-operations-type housing was uneconomical for permanent occupancy because of the greater number of days of hospitalization for respiratory disorders, and the long-term effects of inhalation of coal dust.15

All authorities also agreed that, if further construction had permitted, women's efficiency would have been promoted by some additional measures for privacy in permanent quarters. Major Craighill commented, concerning nurses' housing:

The use in a few overseas areas of large open barracks for nurses was found unsatisfactory. It seems apparent that women value privacy more than do men, and living together under these circumstances tended to increase tension.16

The second WAC Director also noted:

Lack of privacy in housing affects mental and physical health of women. It is

essential that housing scales be established that will assure more privacy. The

contrast between living conditions of WAC officers and WAC enlisted personnel

would be more equalized if partitions are established in barracks to provide

cubicles.17

These recommendations were generally in accord with those concerning permanent peacetime housing for men, in which cubicle-type quarters were also deemed superior where circumstances permitted.

Dayrooms

Women had particular difficulty in adapting Army dayrooms to the needs of a permanent unit. The Army-issued furniture was heavy and depressing and could seldom be made homelike by any feats of ingenuity. While many men apparently did not seem to mind the bleakness, WAC company officers pointed out that for a woman the dayroom was a substitute home-the family parlor in which the younger woman entertained her guests, and the fireside which the older women preferred to going out in the evenings. Attractively furnished dayrooms, said one authority, "go far toward offsetting the harmful effect of regimentation on women."18 For women who did not date, there was literally no other place to spend most evenings except perhaps lying down in a double-decked bunk.

The problem of contriving cheerful dayrooms was increased by the fact that not one but two were needed. By social custom. women entertained their dates in their "home" instead of going to the men's home, yet a dayroom filled with dating couples dancing to a jukebox was scarcely a comfortable place in which older women and nondaters might lounge about in fatigue clothes and bathrobes. It was seldom found a wise solution to forbid daters the use of the dayroom, since, as Major Craighill noted:

All women personnel need a dayroom in which they can lounge informally together, as well as a recreation or reception room in which they can entertain men. If adequate facilities are not available, the incidence of pregnancy and venereal disease is likely to increase.19

[521]

The British had noted a similar need for two rooms:

The gregarious are well cared for by wireless,

games, concerts, and dances, but more quiet rooms are needed by women who wish

to relax.20

Therefore, as the best possible solution under existing circumstances, most WAC units attempted to partition their dayroom space into two parts, or converted the noncommissioned officers' quarters in each barracks to tiny sitting rooms with facilities for writing or sewing. Furnishings were bought with private funds, sent from home, or begged, borrowed, or scrounged from local women's clubs, sorority sisters, churches, or charitable organizations. It was seldom that a WAC unit in the field any length of time did not somehow contrive a cheerful dayroom and a date room.

However, this practice was ended when the Army, early in 1945, forbade solicitation of basic dayroom furnishings from civilian organizations. Another circular prevented the use of company funds for the purchase of lamps and floor coverings.21 For WAC units sent out after this date, any solution appeared difficult.

Hairdressing Facilities

During the first year of the Corps' existence, the provision for women of the equivalent of the men's barbershop was left to local initiative. Some stations already possessed a civilian-operated hairdressing shop for nurses and civilian employees; others did not and expressed some uncertainty as to what if any funds could be used to provide it. Such facilities often appeared even more needed by Wacs than by civilian women, because of the regulation that hair must not touch the coat collar. To meet this requirement, many women needed permanent waves every two or three months. While the women could usually wash, set, and cut their own hair, the home permanent was not yet generally on the market.

Since the six-day work week left Wacs little time to patronize city facilities, Director Hobby recommended and the Chief of Engineers approved a directive which, at the end of the first year, authorized partitioning off part of the Wac dayrooms and the installation of water connections, if the unit could equip and operate the shop. There still remained considerable field confusion as to the financial authorization involved, and a year later a War Department directive defined the application by Army Regulations. Unit beauty shops and barbershops operated by enlisted personnel for their own use were permitted to be defined as "minor profit-making activities of a unit fund." Civilian-operated post barbershops and beauty shops were specified as functions of the Army exchange, with provision for purchasing from a unit any equipment that it had already bought.22

In another addition to regulations, permanent wave operators were required to have a state license, and authority was published for expenditure of unit funds for the required insurance. Director Hobby also requested and secured permission to include in overseas shipments some women who possessed licenses as hairdressers in addition to the military skill for which they were selected.23

[522]

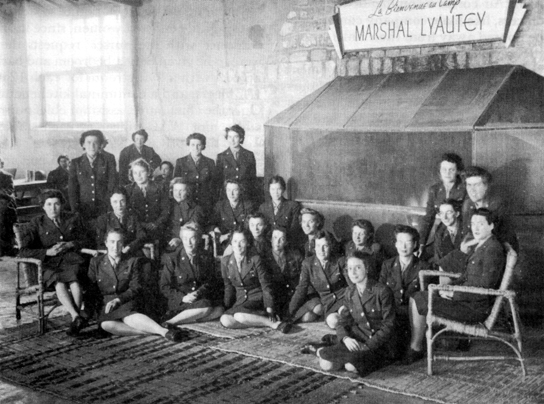

RECREATION ROOMS for enlisted personnel at Brisbane, Australia, above, and North Africa, below.

[523]

Company Officers' Quarters

For economy, WAAC Headquarters had been forced to consent to construction of company officers' bedrooms and latrine in a wing of the same building that housed the WAAC orderly room, supply room, and recreation room. By the end of 1943, reports from every command indicated that the economy had the unfortunate effect of lengthening the company commander's working day to 24 hours, since she was accessible at any hour to visits from company members, unless she arbitrarily denied herself. There was also a tendency to summon her in minor accidents, emergencies, and problems that might properly have been handled by the first sergeant.

As a result of an inspection trip, the Army Air Forces recommended that WAC officers, like male company commanders, be housed away from their units-not off the station, but in a location that would "remove them from the enlisted women so that they would not be on call 24 hours a day." Again, it was too late to correct housing plans after buildings had been constructed; no general relief was ever obtained; although stations sometimes, when other quarters were available, permitted company officers to live elsewhere. In some cases stations went to the other extreme and permitted company officers to live off the post where they were not accessible in any emergency. In the Air Forces this practice was checked by a circular requiring one duty officer to be quartered on the station, although not necessarily in the unit.24

Future Housing

Elaborate plans were drawn up by G-4 Division and the Chief of Engineers for the proposed peacetime WAC housing.25 Privates, corporals, and sergeants in field units were to have hotel-type housing, only two to a room, with 120 square feet per enlisted woman (the wartime officer allowance). Each building was to have a kitchen, a dayroom, and a date room, and bountiful latrine facilities, including bathtubs. Enlisted women might also look forward to even greater privacy and comfort as they grew older and attained the first three grades; there were to be provided two-bedroom apartments for every four such women, each apartment with its own living room, kitchen, and bath. Even in training center barracks, recruits were to have 90 square feet per person, and window shades, hairdressing facilities, a dayroom, and a date room, a storage room, and adequate laundry and latrine facilities.

Junior officers were not quite so well off as top-grade enlisted women, since in accordance with the nurses' requests they were to be given only a bedroom and bath apiece, with a living room for each 12 to 18 officers, and a communal kitchenette. Only the chief nurse, assistant chief nurse, and senior WAC officer at each station would have private apartments.

Such accommodations, which met and surpassed most of the proven needs of women for privacy and home comforts, could actually, it was discovered, be provided at a lower average cost to the government than housing for Regular Army enlisted men and officers. This surprising

[524]

saving resulted from the fact that most career Army men were married and drew dependents' quarters, to which women were not entitled. The provisions for women were designed to provide a semblance of home life for career women who would perforce be denied children or settled married life if they remained with the Army. Most of these plans remained on the drawing board, since the Army would not for years be in need of much new construction.

In most respects the WAC unit mess was identical with similar Army messes, except for detached benches at the tables. Many messes also had any number of adjustments needed by women and contrived by the unit or by post carpenters. These included duckboards to limit the depth of sinks to a woman's reach, shelves and wheeled carriers to minimize lifting and bending, and similar mechanical contrivances to make it possible for women to manage heavy equipment designed for men. No catalog was ever made of such local inventions, although one had been begun by WAAC Headquarters before operating functions were transferred to the Army Service Forces, which discarded the material.26

Wherever local authorities permitted, WAC messes frequently took on an appearance quite different from that of the average men's mess, chiefly by the use of color, potted plants, and sometimes curtains, all either salvaged at no expense or acquired from unit or personal funds. One staff director recalled later, "I'll never sec a sweet potato vine without thinking of the WAC.27 At holiday seasons, decorations were generally put up, evergreens at Christmas, autumn foliage for Thanksgiving, bunting on patriotic occasions. Quite often a piano or phonograph was borrowed from recreation buildings and installed in the mess hall to provide music with meals. The WAC unit mess invariably tended to take on something of the function of the kitchen in pioneer homes a center for family life, visiting, and entertainment. Where there was no unit mess, and Wacs ate in consolidated messes or in city restaurants, a sense of unit solidarity was more difficult to maintain.

Consolidation of Messes

In spate of the vital role played by unit messes in morale and company unity, their maintenance presented certain difficulties. The provision of kitchen police details to staff these messes invariably caused complaint in headquarters offices, which lost a WAC working day once or twice a month. For this reason. Director Hobby for a time considered closing WAC unit messes, and allowing Wacs to eat with men at large consolidated messes where these existed.28 Inquiry soon revealed that in the few cases where Wacs did not have separate mess, company commanders reported not only loss of esprit, but a serious nutritional problem. In a consolidated mess, the food was often too heavy and fattening for women. Also, women, after a hard day's work, were found to be going supperless to bed rather than change to clean uniforms, walk some distance to the consolidated mess, and brave the attention

[525]

of hundreds of men. Women also often skipped breakfast for the same reason, substituting oversweet snacks or candy bars at the post exchange. On the other hand, both health and morale were improved when women could enjoy a leisurely meal at their own small quiet mess, where they did not have to dress or walk far, but could sit and talk, read mail, or listen to records.29

On discovering this. Colonel Hobby dropped the idea of consolidating messes, and instead requested that they not be consolidated without War Department consent to each exception. G-1 Division concurred, and a provision to this effect was placed in the first WAC Regulations in November of 1943. At once the Army Air Forces requested that authority to make exceptions be given to its headquarters, and Director Hobby agreed that such delegation might safely be made even further, to each general officer who had a WAC staff director on his staff. However, General Dalton instead decided that the authority should be given to "local commanders," which would permit station commanders to consolidate men's and women's messes without consulting higher authority. Over Director Hobby's nonconcurrence in this wording, he directed publication of a circular to this effect.30

Upon discovering this publication, Director Hobby renewed her recommendation to the General Staff, fearing damage to women's health if they did not eat regularly. Finally a compromise was obtained when the Army Service Forces agreed upon the wording "the Commanding General who is responsible for the operation of the post, camp, or station.'' While this did not necessarily bring the decision up to the level of a command having a WAC staff director, it prevented most station commanders from acting without higher consideration of the factors involved. In view of the central role of the WAC mess in maintaining unit morale and efficiency, its abolition was ordinarily regarded by WAC advisers as a last resort where a unit had shrunk beyond any reasonable hope of maintaining its own mess 31

WAC Master Menu

It quickly became known to every mess officer that Wacs did not want, and could not eat, all of the items on the standard master menu for men, which were issued to each unit on a station. In general women wanted less potatoes, bread, flour, lard, syrup, pork, and other heavy or fattening foods, and more fresh vegetables and salads. Even of foods popular with both men and women, such as eggs, lean meat, and coffee, lesser quantities were consumed by women.

For the first years of the war, adjustment was attempted on a local level, with the WAC mess sergeant ordinarily adept at swapping mayonnaise for salad oil, potatoes for lettuce, and large quantities of pork for small steaks. By the end of 1944, research by the Office of The Quartermaster General, with control tests at selected installations, had established a WAC master menu that made swapping

[526]

unnecessary, and that authorized issue of the types and quantities of food proven by experience to be needed by the average WAC unit.32

Not only did such a master menu prove useful in improving appetite and controlling weight, but considerable saving to the Army resulted. During 1945, studies showed that the average cost per man per day was $0.58015, and per woman $0.52264. This, for the WAC strength of 100,000 as compared to an equal number of men, would result in a yearly saving to the Army of $2,099,115.00, provided that WAC unit messes were maintained.33

Controversy over the main body of WAC Regulations was mild compared to that which accompanied the writing of the detailed uniform regulations after the Corps' entry into the Army, and which soon witnessed the Air Forces in mortal combat with the Ground Forces over lapel insignia, and the WAC in unsisterly dissension over the disposal of the necktie. Such commotion over articles of uniform was not unknown to the Army, where old-line officers could not recall any item changed without lengthy dissension. It was therefore not until the first days of 1944 that clothing regulations could be agreed upon,34 and frequent amendments were necessary thereafter.

Director's Proposals

After the WAC's admission to the Army, possibly the most frequent cause of criticism was the continued use of the mismatched uniforms-non matching skirts and jackets of chocolate brown and mustard yellow shades-which women had received during the early days of the expansion program. Many of these, turned in by the 15,000 women leaving at the conversion, had been repaired and reissued to new recruits. In late December of 1943 Director Hobby submitted to the Army Service Forces a plan to eliminate them, noting that "These uniforms, which are obviously not of authorized shades, have had definite reflections on recruiting and on the morale of the troops." Since there was now a surplus of uniforms of the authorized shade, she asked a liberal salvage policy, whereby women need not wait until mismatched items were badly worn before turning them in. This request was approved by The Quartermaster General, but disapproved by Requirements Division, ASF, since it was standard Army policy that earlier procurement must be worn out, and reissued as long as repairable, before new stocks were used. 35

The issue of secondhand clothing to new recruits was also a cause of criticism. The Director informed the ASF:

Innumerable reports to this office have indicated that the issue of used or substandard uniforms is disparaging to morale . . . and detrimental to enlistment in competition with other women's services.

Since other service women got a clothing allowance with which to purchase new

[527]

clothing, she asked that no further Class B clothing be issued to new recruits, and that women already in the field be given one new skirt and jacket if their entire issue had been secondhand. This proposal was also rejected by Requirements Division, ASF, insofar as it concerned women already in the field, but it was agreed that new recruits should be issued one new skirt and one new jacket.36

A third proposal from the Director concerned an off duty dress similar to those already authorized for the Army Nurse Corps and Army physical therapy aides. Before the conversion, Waacs had been able to discard ill-fitting or mismatched uniforms in favor of civilian clothing on off-duty occasions or when on leave, but this was no longer possible under Army status. Even had the tailored uniforms been adequate, there appeared, in the opinion of all women's services, to exist some universal psychological need of servicewomen for feminine-type attire for social occasions. The WAVES, SPARS, and Women Marines therefore authorized dress uniforms for both officers and enlisted women, while Army and Navy nurses had dress uniforms, plus summer and winter off-duty dresses in a simple shirtwaist style.

In consideration of the expense involved, the Director did not ask for the issue of such items for Wacs, but only that women be authorized to buy an approved model if they wished. She added, "It is considered by this office that a provision for an off-duty dress is necessary as a matter of well-being." However, Army Service Forces disapproved this request, stating that the WAC was not analogous to the Army Nurse Corps and that enlisted men were not allowed to buy off-duty dresses. Although Director Hobby addressed this request to the General Staff by authority, of Circular 289, as a matter of well-being, General Somervell's office returned it disapproved without allowing it to reach the War Department.37

As one alternative, the Director asked that The Quartermaster General consider a different fabric for the stiff and heavy summer uniform, one that would eliminate wrinkling and improve the fit. In January of 1944 the Quartermaster reported no solution and recommended that "the importance of the problem be considered insufficient to warrant a change in the fabric of the summer uniform." The retention of the men's-weight 8.2-ounce khaki was approved by the ASF and by G-4.

Likewise bypassed was the Director's attempt, concurred in by The Quartermaster General, to add more color to the uniform by the addition of an inexpensive yellow cotton scarf and gloves, similar in effect to the Women Marines' red scarf and the Navy women's blue or white shirts.

A sixth proposal, which also met defeat, was that of redesigning the WAC jacket, summer and winter, since nothing had yet been done to correct the inadvertent error of the Philadelphia Depot in respacing the jacket buttons. The Quartermaster General concurred, recommending that three buttons be used in future procurement instead of four. However, ASF's Director of Materiel refused to allow the Quartermaster to undertake developing a new design.

A seventh refusal was that of the Director's renewed request for a garrison cap

[528]

like the men's. She noted that men had both dress and garrison caps and that "The wearing of a garrison-type cap has been found necessary for many jobs to which WAC personnel are now assigned," the number of which "has been increased to 239 different jobs." Wacs, she said, had also been sent overseas where cleaning and blocking facilities for the dress cap were not available. Although the Director addressed her request to G-1 Division of the General Staff, as an Army-wide matter, it was disapproved by Requirements Division, ASF, on the grounds that there was a large supply of dress caps on hand.38

Although such surplus stocks of caps and uniforms were allegedly on hand in sufficient quantities to make changes impossible, in actual practice, the Director noted, there had been little improvement in supply. Stations reported not only that they here unable to obtain maintenance stocks and replacements for salvaged items, but that women continued to be shipped by training centers without complete clothing issue, and sent to cold climates without either caps or coats.39

Station commanders and inspectors in the field repeatedly protested to the Director the state to which the appearance of the WAC uniform had been reduced, in this second winter of the Corps' existence, by the failure to take action against existing defects. Inspector General reports noted that the clothing of Wacs in units inspected was of poor quality cloth, secondhand, and showing signs of much wear even when first issued, and that "Such clothing does not conform to AR 850-126 [for men] which states 'correctly fitted smart uniforms are a basic factor in the creation and maintenance of morale.' " The report of one service command caustically recommended that each Wac get "at least one complete outfit of outer garments suitable for appearance in public." 40

Early in 1944 members of Congress began publicly to criticize the WAC uniform. One senator informed the press in a widely quoted interview that the uniform was responsible for the lag in enlistments and that "a woman need not look like a man to make a good soldier."41 There was no doubt that the public sided with the criticizing congressmen. A Gallup poll in January of 1944 asked, "Which uniform worn by women in the Armed Services do you like the best?" and received replies: 42

|

Percent |

|||

| All replies | Men only | Women only | |

| Weaves or Spars best | 49 | 40 | 57 |

| Marines best | 26 | 28 | 24 |

| WAC best | 15 | 17 | 13 |

| Undecided | 10 | 15 | 6 |

Soon after the Director's move to G-1 Division, she was charged by the Meek Report with responsibility for failure to improve the uniform. In reply, the Director presented General Marshall with a list of her previous recommendations to the

[529]

ASF, from August 1942 to the current date, all disapproved.

The Chief of Staffs problem in determining needed action was not greatly clarified by Congressional attitude toward the matter. Unfavorable publicity originating in Congress continued throughout the spring of 1944. In one case a Representative from New York released to the press a letter to Colonel Hobby-which she had not yet received-headlined LACK-LUSTER WAC UNIFORMS HELD FACTOR IN RECRUITING LAG. The Congressman alleged that the uniform lacked "military pertness," and should be "piquant yet dignified, stern yet charming," and more "coruscant." He urged that New York stylists be allowed to redesign the entire uniform, which they had assured him they would, and as for the cost, he stated:

From a strictly military and economic point of view, it may be argued that there is a stock pile of half a million old WAAC uniforms. What of it? They should be used for junk. They are utterly valueless. . . It is worth putting this stock pile on the scrap heap if you can appreciably recruit your full quota of Wacs.43

The language of such press releases contrasted considerably with that of a private letter, entitled "Senate Investigation of the WAC," which was shortly received from the Truman Committee, more properly known as the Special Committee Investigating the National Defense Program. This committee displayed particular interest in the stockpiles of unused material procured in the days of hoped-for expansion of the WAAC, and requested justification of the Army's action in the "reduction in WAC enlistment program,"' which had caused such surpluses. While the War Department was easily able to convince the committee that it had not deliberately cut down WAC enlistments, it was obvious that remedial action could not include any move to discard stockpiles of unsatisfactory uniforms.44 Therefore, General Marshall's decisions were necessarily those which could be put into effect without much financial expenditure.

Chief of Staffs Approvals

Among the first of the Director's proposals approved by General Marshall was that of a chamois-colored cotton scarf and gloves, both actually less expensive than the leather gloves alone, but adding a becoming color to both summer and winter uniforms. The official "chamois" color was actually a pale yellow.

Possibly even more popular with the women was the new garrison cap, similar to the men's but designed to fit over women's longer haircuts. For this item, the ASF withdrew its disapproval before General Marshall directed adoption.45 Although costing only about 39 cents in the summer version, the cap was so becoming, and so essential for many types of duties and for overseas stations, that the WAVES and women Marines shortly adopted a cap of almost identical cut. The combination of new and becoming cap, scarf; and gloves was found to add considerably to

[530]

the smart appearance of the WAC uniform without the necessity for further and more expensive changes in the design of the uniform itself.46

Concerning the search for a nonwrinkling material for summer uniforms, it was found that a number of tropical worsted uniforms in the standard design were already on hand. These had been procured in the days when uniforms were issued to WAAC officers but had arrived too late, just as this practice was discontinued in favor of a monetary allowance for officers. With hasty procurement of a few more, it proved possible: to give every WAC enlisted woman one such outfit during the summer of 1944.

The change wrought in the appearance of the WAC summer uniform by the difference in weight of materials was remarkable. Impartial observers now stated that a Wac in the summer, from being the: most unbecomingly dressed of all servicewomen, now had become the smartest looking. So great was the difference from the stiff men's-weight cotton that the Chief of Staff later in the spring directed that not one but all cotton uniforms be replaced by tropical worsted. This was more than Colonel Hobby had asked, and drew protest from The Quartermaster General, who was obliged to postpone for two months delivery to sales stores of male officers' tropical worsted uniforms. Nevertheless, the Chief of Staff did not change his mind; the cotton uniforms were thereafter used only for training centers, the Pacific area, and certain other climates and duties.47

The last new item approved was the off-duty dress, somewhat similar in design to the approved off duty dress of the Army Nurse Corps. General Marshall first directed that it be procured by the Quartermaster for resale to Wacs at cost. After learning that the dresses, although attractive and comfortable, would cost only about $10 each, he decided that each enlisted Wac should be issued one without cost. A jury of enlisted and officer Wacs shortly thereafter surprised Colonel Hobby by rejecting a smart model by a famous designer in favor of a more military basic dress with a collar for insignia. The dress was made up in a becoming beige shantung for summer, and in a gray wool shade close: to the officer's "pink" for winter. The Quartermaster protested that immediate procurement was impossible, but at General Marshall's urging was nevertheless able to get the summer dresses out by summer.48

The off-duty dress proved well-fitting, being the first garment for which women's instead of men's sizes had been used in procurement. The Office of The Quartermaster General warned the field that "the patterns from which these dresses are made are basically different from the patterns used for jacket and skirt issue items of clothing; hence, the sizing will correspond to the civilian 'ready-to-wear' sizes." 49

In general the dress proved most successful: requests for samples carne from the Canadian joint staff and from other nations. Only in overseas areas were washing difficulties reported. In the United States there was much competition for issue of the dress: first priority was given to the Military District of Washington, where

[531]

women were exposed to the view of the War Department; second, to recruiters, who were exposed to the public: third, to the Fourth and Eighth Service Command areas, which were exposed to the hottest summers; all others followed in order of receipt. The winter dress was issued, in the last winter of the war, to all commands.50

In addition to authorizing such new items, General Marshall also directed that the mismatched winter uniforms be replaced by those of authorized shade already in warehouses, and that Wacs be supplied new uniforms from the same source and no longer issued secondhand outer garments. The Quartermaster General welcomed this move, stating that the Army Service Forces policy of hoarding new uniforms had been "a shortsighted view . . . detrimental to the further recruitment of members."

The approval of the last of these changes in May of 1944 left the WAC uniform program in a state satisfactory to Director Hobby, except for specialized work garments that were to be added at a later date. The WAC now had a wardrobe comparable in neat appearance to those of the other women's services.

The WAC's service uniform remained, with a few modifications, where General Marshall had left it at this time. Even the many improvements did not make the public universally happy or silence all of the self-appointed critics. Enlisted women, who had seemed unanimously opposed to the stiff WAC cap, now in sonic casts perversely mourned its loss, saying, "I loved those peaked hats"; "They looked so much more military"; "Could you please reconsider your order?" 51

After the appearance of the new items authorized by the Chief of Staff, Congress also was heard from with a "Complaint that Soldiers Receive Less Clothing than Wacs. 52 In reply, the War Department stated its final Wk clothing policy: "As a result of two and a half years experience with women personnel in the Armed Services, the Army has found that just as in civilian life women require more clothes than men.53 The "more" was not, however, prohibitive in cost, amounting finally to only about five dollars a year per person, which would have been about $:100,000 for peak WAC strength, less than one fourth the amount women saved the Army by eating less.54

In quantity of issue, G-1 Division noted that there were only two real differences, the chief being that Wacs got of duty dresses, unlike men but like the nurses and all other women's services. The other difference was in the number of pairs of shoes in the initial issue, where men got two and women three, in order to provide different heel heights for service and field. In this case, G-1 noted that the Army actually had five types of men's shoes, which were issued as needed for special operations and climates, as against the WAC's two types, service and field, for all uses.

The Overcoat

The overcoat for enlisted women never offered any great problem after the issue of both overcoat and utility coat was restored. That of the officers was a different

[532]

matter, for their only authorized coat remained the rough field coat. The old WAAC: "beaver" coat of light olive drab, comparable to the enlisted women's overcoat, was not restored because of shortages of its particular material, and in any case had never been authorized for nurses. As a result, women officers began wearing unauthorized overcoats of various designs and colors, especially "pink" coats modeled upon those of the men -likewise unauthorized, but worn by many officers. To stop this practice and standardize the coat, both Wacs and nurses agreed upon a coat cut exactly like the enlisted women's, but of dark olive drab to match the winter uniform. Its adoption carne too late to standardize field practice to any great extent.55

Battle Jacket

The only other addition to the service uniform after 1944 was the battle jacket, resembling the civilian lumber jacket, first procured in England by the European theater. As European theater personnel, male and female, began to bring battle jackets to the United States, it proved impossible to stem the tide of their popularity, and it was necessary to authorize their wear by men in the zone of the interior. :Many women officers also began to purchase them, and since the men's jacket could not be purchased by women, The Quartermaster General, after consultation with prominent New York stylists, produced a design for women. This lacked the pockets of the men's version, and had more of a bloused effect, since the men's bepocketed jacket had an unbecoming appearance when worn by short or plump women. Except for those individuals who had received them in Europe, the garment was not issued, but purchased at the wearer's expense.56

Necktie and Handbag

The complexity of setting up rules for a new group in an army was well exemplified in a minor controversy over the necktie and the handbag. The shoulder strap of the handbag had originally been worn on the right shoulder, crossing the body diagonally, with the handbag resting on the left hip. This system was abandoned in WAAC days because the diagonal strap wrinkled the shirt and was awkward to put on and off; when worn by women of heavier build, it cut beneath the bust line to produce an undesirable profile. The rule was therefore changed to authorize wearing of the handbag on the left shoulder, hanging straight down. This method proved even worse; most women did not have large enough shoulder muscles to prevent it from slipping off, so that many handbags were lost and police reported an epidemic of handbag-snatching. Also, tailors reported that Wacs hunched the left shoulder to keep the strap on, and were rapidly becoming deformed; the marching gait was also uneven because the left arm swing was restricted. The original diagonal system was therefore restored, although later those who wished were allowed to remove the strap and

[533]

ON LEAVE IN PARIS, 1945, Note of-duty dresses, above, and battle jackets (left), below, worn by the women.

[534]

carry the purse in the hand when not in formation.57

Tucking the necktie into the shirt in the Army fashion was likewise forbidden because it added a certain undesirable bust fullness to individuals not in need of additional fullness in that respect. This provision had also shortly to be dropped in favor of the original system, for Wacs complained that the necktie hanging loose flapped in their eyes, became caught in machinery, was dipped in soup, or caused them to be arrested by military police who were not aware that the WAC had a different rule. The extra bust fullness was eventually deemed the lesser evil.

Work Clothing

The WAC uniform regulations from time to time added authorization for various types of work clothing that had been proved essential to replace the drivers' cotton coveralls, which from the first had proved an extremely poor substitute for either summer or winter work garments.

The herringbone twill cotton coveralls, as originally issued, had been designed only for tire-changing and emergency repairs. Both one- and two-piece models were used at different times, but all were ill-fitting and unbecoming garments. They were too hot for summer and for work in kitchens, too thin for protection in winter, too clumsy for use in laboratories, too unsightly for chauffeurs of staff cars, too unsanitary for hospital work. In warm climates they scratched the women's skin, causing rashes and infections, and some women proved allergic to the dye used in them. Their weight made them difficult for women to launder in the barracks, especially when the garments were grease-stained, and women who had only one pair found that they would not dry overnight.

Even in Auxiliary days, various Army commands bombarded Director Hobby, whom they considered responsible, with requests for a substitute for the coveralls. The Army Air Forces requested a different type of work garment for Waacs engaged in aircraft maintenance, declaring that the drivers' coveralls lacked the necessary tool-holding devices for a mechanic's efficiency and were not designed for safety around moving machinery. The AAF's First Mapping Group also asked for medium-weight culottes for Waacs on duty in photo-laboratories and darkrooms: "The culotte uniform will improve the operating efficiency of personnel to such an extent as to warrant its procurement." 58 Such early requests were all disapproved by the Army Service Forces.

By mid-1944, complaints concerning the WAC herringbone twill coveralls had come in from every part of the world where Wacs were stationed, including the four major overseas theaters. In the United States, the most complete study of the deficiencies of the herringbone twill coveralls was made in the Air Forces' testing center at Wright Field. It found that the material was too thick to allow circulation of air during physical training, long sleeves and trousers limited free movement during formal exercises, the allowance of two per person was insufficient for duty assignments on flight lines or in warehouses, and the material was too hot for wear in warehouses. The uniform was supplied only in three sizes, and "The woman who needs a size 10 is a very

[535]

pathetic figure in this garment." Its ill-fitting cut and limited size range made the garment an accident hazard; its poor fit "is humiliating to the enlisted woman and causes needless morale problems": and the weight of the garment presented a laundering problem. This study was, however, rejected by G-4 of the General Staff on the grounds that the evidence of a single command was insufficient.59

Nevertheless, as a result of the cumulative requests, by the summer of 1944 the Office of The Quartermaster General was engaged in adapting the nurses' seersucker slacks design to wool and khaki for both Wacs and nurses. Unfortunately for speed of action, favorable consideration was not given to the simple request of most areas for a slacks suit of the same weight and general appearance as the men's. Instead, the Quartermaster attempted to employ the latest ideas of the Chemical Warfare Service regarding protective clothing in case the women should enter a gassed area, and the latest camouflage color.

As a result, at the end of the summer of 1944 there had been developed and approved a garment in poplin, not twill, in a muddy olive drab instead of the men's khaki, and with various flaps, drawstrings, and buttons for protection against gas. To this, the Pacific theater continued to object, stating that poplin was not mosquito-proof and that there was no reason why women's uniforms should be made unsightly with protective coloration and gas-proofing when those of men in the same area did not need these features. Eventually, a trim regulation khaki slacks suit, resembling the Army summer uniform, was approved, and the same design was applied to wool trousers. However, this action came too late in the war to be of anything but future interest. The experiences of World War II had demonstrated beyond doubt that Wacs and nurses in overseas theaters, and those in active work in the United States, would inevitably require slacks resembling men's trousers in design and material.60

In the same months The Quartermaster General also developed various types of clothing for even rougher cold-weather wear. The "layering" principle currently employed for men's garments was also applied to women's, particularly in a field jacket and trousers with a windproof outer cover and wool inner-liner. For arctic wear, pile-lined overcoats and hoods were also developed. Except in the coldest weather these garments were generally less favorably regarded by overseas theaters than ordinary slacks, partially because of their bulkiness and clumsiness.

Even after suitable work clothing was developed, stations in the United States were able to get it only for women whose occupational specialty number was on the approved list of "outdoor workers," or, in the case of winter clothing, if the station was located in the northern part of the United States. Many requests from field stations indicated that certain women not listed as outdoor workers, such as stock clerks; nevertheless often performed active work outdoors or in unheated buildings. In addition, stations in the southern zones of the United States complained that they were unable to get WAC drivers the necessary winter trousers and warm underwear, these sometimes being needed even more than in northern climates because there was no authorization for vehicle heaters in the south.

[536]

In response to these requests, Director Hobby proposed that the commanding general of a service command be authorized to define "outdoor worker'" and to determine when the climate required warm clothing. The Quartermaster General, fearing that this privilege might be abused, consented only to permit the commanding generals of service commands to declare women outdoor workers to no more than the extent of one fourth the company in Gone 3 and one third in Zone 2. This system was approved by Requirements Division in January of 1944, and put into effect.61

Hospital Uniform

With the move of the Director's Office from the Army Service Forces, the policy of providing no work uniform for hospital Wacs changed gradually. Soon after Major Craighill's appointment as Medical Department consultant, she discovered warehouse stocks of surplus blue cotton uniforms, now outmoded for Army nurses. Since no cost was involved, the Army Service Forces consented to their issue to Wacs working in hospital wards. However, the dresses were not available in all size ranges, and caused Wacs to be mistaken for the civilian employees who also wore them. Therefore, in September of 1944, G-4 Division authorized the wearing of the cooks' white uniforms in hospitals. This immediately proved unsatisfactory, since the cooks' uniforms had been designed to be worn over other clothing, and did not provide sufficient covering. Next; The Quartermaster General's Office experimented with the dyeing of nurses' white uniforms, but this also proved unworkable.

Finally, just before V-E Day, the Quartermaster General was authorized to provide green poplin dresses especially for hospital Wacs. Upon the advice of his civilian consultant; Miss Dorothy Shaver, vice-president of Lord & Taylor, the material was changed to rose-beige chambray. An extremely practical and becoming dress was evolved, and issue of nine dresses to each enlisted woman on hospital duty was authorized, a number that permitted Wacs to make use of hospital laundries as did other employees.62

Wacs not on duty in hospitals, but working after hours as volunteer nurses' aides, received published authorization to wear the usual blue and white cap and apron of the volunteer aide.

The Service Shoe

Another reform made by the last year of the war was in the fit of the WAC shoe. Throughout 1943, attempts to improve the shoe brought only complaints that new issues were worse than the previous one. In one "improved" type of shoe, salvage rose from 20 to 50 percent and wearers complained that it lacked arch support, did not fit the female foot, was too wide, too stiff, and with too low a heel for office wear. In 1944 the men's foot measuring outfit proved unsatisfactory and was replaced by a new Foot-Measuring Outfit, Women's, one for each detachment, in order to eliminate the problem of

[537]

ordering wrong-sized shoes. With this improvement, and with The Quartermaster General's decision to issue only shoes made on government-owned lasts, most problems in the fit of the service shoe and the field shoe here eliminated.

The Quartermaster General concluded that earlier troubles had not arisen from poor shoes but from imperfect fit. Earlier shoes had been procured on as many as twelve different commercial lasts and, while each was of good design and construction, attempts by field companies to order by size were thwarted as the "result of stocking shoes made on different lasts under the same stock number." 63

No similar solution was ever found to the need for an athletic shoe, since neither the high-laced field shoe nor the medium heeled service shoe proved suitable for the required physical training. Quartermaster Corps investigators late in 1944 found that Wacs were wearing for this purpose and for kitchen duty what remained of the discontinued issue of tennis shoes, in "an advanced state of disrepair," as well as bedroom slippers, moccasins, and civilian sports shoes, presenting a "shabby and unsightly" appearance. The issue of tennis shoes could not be resumed, since all available materials were needed to produce canvas rubber footwear for combat men.

The Quartermaster General's Office was able to devise a substitute of noncritical materials, but the Army Service Forces and the General Staff refused to permit procurement of this item for women. Since WAC physical training was seldom done in public, the item was not, in the women's opinion, unduly important; most Wacs would have been glad to dispense with the physical training as well as with the shoes.64

Stockings

In tropical countries, and in semitropical areas of the United States, it proved virtually impossible to keep the Wacs in stockings. The five pairs of rayon stockings per quarter-one and two thirds pairs a month-which had by this time become the authorized issue, deteriorated badly in hot climates, forcing the women to buy their own or go stockingless. In any event, many women preferred to leave off stockings in the interests of comfort. Both the Air Forces and the Ground Forces recommended to the War Department that Wacs be authorized to omit stockings from the uniform between reveille and retreat, on the post only, at the discretion of the commanding officer. On the other hand, health authorities pointed out that at least clean socks or other foot coverings were required in the interests of health and shoe preservation.

The socks proposal was vetoed by The Quartermaster General's Office, which had not procured women's cotton socks except for use with the exercise or tennis shoe; long since discontinued. The stockingless state, particularly off the post, was frowned upon by both the first and second WAC Directors, since it became only those whose legs were shapely, well-tanned, and well-shaved-and there were, all too obviously, many Corps members not thus qualified. Finally, after V-J Day, a new authorization was published for eight pairs of stockings per quarter in tropical countries and Zone 3 of the United States-a provision that was supposed to

[538]

end the need to go stockingless. However, nationwide reports from numerous interested observers indicated that such was not necessarily the result in all cases.65

Insignia

The WAAC lapel insignia of branch had always been the Pallas Athene, but under the WAC legislation the Corps was designated, not a basic branch, like Infantry or Cavalry, but a component of the Army. It thus became the only component to have its own insignia, which was ordinarily issued to women at training centers regardless of the branch that was their ultimate destination. After the conversion, the question at once arose from many field stations whether Wacs should continue to wear the Pallas Athene, or should change to the insignia that men would have worn if filling the same position vacancy-Quartermaster Corps. Signal Corps, Medical Corps, and the like.

One strong faction, composed of the Army Air Forces and certain of the Army Service Forces' administrative and technical services, insisted that women should wear the insignia that would have been worn by a man assigned to the same job. In fact, even in Auxiliary days WAAC Headquarters had noted with some amazement that The Inspector General had ordered WAAC officers in his office to violate War Department directives by putting on Inspector General insignia. Many air bases and some Signal Corps stations had unofficially been reported doing the same thing, and it came as no surprise that these agencies considered women entitled to wear their insignia as soon as Army status was achieved.66

The opposing faction consisted of the Army Ground Forces and certain headquarters agencies of the Army Service Forces. ASF's Military Personnel Division proposed that the women should continue to use up stocks of the old Auxiliary buttons, cap insignia, and lapel insignia, "thus maintaining the Corps as a separate unit" from the Army. General Dalton stated:

The WAC may be considered in effect as a separate corps or another service. As such it is appropriate that the WAC have distinctive lapel and collar [branch] insignia as prescribed for other arms and services .... The wearing of the lapel insignia of the arm or service to which WAC personnel may be detailed would be unsatisfactory as it would add unnecessary administrative complications concerning orders of assignment and relief, designation on rosters, strength returns, and signature legend.67

The Ground Forces also reported itself as horrified at the prospect of seeing crossed rifles, sabers, or cannon on women's uniforms, even though the woman was filling a job that would entitle a man to wear them. To the Air Forces' proposal, the Ground Forces sent a reply which the AAF interpreted as a deadly insult-that it was very well for women to wear Air Corps insignia, but not that of "a combat arm."68

The only compromise that could be reached in the first WAC uniform regula-

[539]

tions was a weak one: the insignia of another arm or service would be worn during the period that a WAC was "detailed in or assigned to" that arm or service. This phrase was virtually meaningless: detailed in or assigned to was technically used, for officers, to describe a change in branch which required War Department orders "by Direction of the President." 69 Since such orders were never used for enlisted personnel, there was extreme lack of uniformity in field practice. The Air Forces put its women in its own insignia, and, to insure against misunderstandings in this respect, secured a sweeping directive detailing all its WAC officers in the Air Corps by direction of the President, with provisions for change to the appropriate arm or service in the case of technicians.70 The Ground Forces did not authorize a change in insignia, and various other services left the matter up to stations in the field, which were understandably confused about the whole matter.71

This confusion eventually made some further Army-wide clarification necessary. Instead of simplifying strength accounting, the retention of a separate designation by Wacs assigned to other arms and services actually forced statistical control units to add another column to reports, with apparent resulting discrepancies in reported personnel of Signal, Ordnance, Medical, and other troops, which were not really understrength but partially represented in the WAC column. The resulting confusion could have been heightened only if statisticians had been forced to carry all Negroes, or all Texans, or all left-handed men, or other minority groups, in a separate Corps instead of in the arm or service for which they were working.

Colonel Hobby's comments to this effect were sent back by General Dalton while her office remained in ASF,72 but upon the move to G-1 Division she was in a position to bring them to the attention of the General Staff: Meanwhile, one Army-wide clarification was achieved by the action of the Air Forces, which inquired whether Wacs might wear Army "distinctive insignia"-the metal devices for officers' shoulder straps and enlisted men's lower lapels, which marked certain regiments, commands, or other units. G-1 Division ruled that assigned women not only could but must wear these, since wearing of a unit's distinctive insignia was required of all members.73

On the more controversial issue of insignia of branch, for over a year the War Department was unable to devise any clarification of the 1944 regulations that would suit all factions. So bitter were the differences over this question that, in 1945, it was necessary to publish a final circular which permitted three different policies in the three major commands. In the Army Air Forces, all Wacs were permitted and required to wear Air Corps or ASWAAF (Arms and Services with the AAF) insignia. In the Army Service Forces, women also assumed the insignia that a man in the same assignment would have worn, but with exceptions made for the Judge

[540]

Advocate General's Department, the Medical Department, and the Corps of Chaplains, none of which would concur in wearing of their insignia by females except when specifically detailed to their Corps by their own action in individual cases. In the Army Ground Forces, it was ruled that under no circumstances, no matter how assigned, or even if replacing men who had worn this insignia, would women ever wear the insignia of the Infantry, Cavalry. Field Artillery. Coast Artillery, Tank Destroyer, Armored Force, or any other Army Ground Forces command.74

Clothing Depots

The size of the Corps was never great enough to permit a system of stocking clothing and insignia comparable to that used for men. In the first months after the Corps' establishment, only WAAC training centers stocked women's clothing; later, two Army depots took over the task of supplying all field installations. This system proving unsatisfactory, in September of 1943 the Director's Office was informed by The Quartermaster General that, under an improved system, five depots would carry stocks of WAC clothing, and over 300 stations in the field would be authorized maintenance stocks. It was soon discovered that the list had neglected to provide for Air Forces Wacs and, after certain comment from that command, Air Forces stations were added.75

In spite of these improvements. field stations reported that their requisitions to authorized depots were still returned with the reply that no stocks were available.76 It was also noted that filling of requisitions for women's uniforms generally required longer than those for men, while salvage and repair were likewise slower, presumably because of the greater distances of shipment or unfamiliar nature of the items. In a later effort to improve the speed of supply, stations at which over 300 Wacs were stationed were authorized to keep maintenance stocks to supply the needs of smaller units in the vicinity. Obviously, however, no system as satisfactory as that for men's garments could be established for so small a group.

Allied Women's Services and the WAC Uniform

The whole progress of the WAC uniform and equipment program was of considerable interest to several of the Allied nations, which desired to equip their newly organized women's forces by lend-lease arrangements for American supplies. A number of WAC uniforms had already been shipped to the French forces in North Africa when, early in 1944, Director Hobby succeeded in getting a War Department directive that any further such shipments would be of a cut distinctive from the WAC uniform, or WAC uniforms dyed a distinctive color.

This rule did not meet with the general approval of foreign forces. The French Military Mission objected on the grounds of time: 100 Frenchwomen recruited in the United States were already awaiting shipment as soon as they could receive complete WAC uniforms, which were desired unchanged because the uniform of the French Feminine Volunteer Corps was "basically the same design and color as the WAC uniform." The Netherlands Purchasing Commission, for its women to serve in Australia, wanted merely different but-

[541]

tons and sleeve patches, and objected to the orange lapel pieces, shoulder straps, and other distinguishing marks which Colonel Hobby suggested. International Division, Army Service Forces, sided with the governments concerned, since men's uniforms were lend-leased unchanged.

It was virtually impossible, in the interests of international tact, to point out to such nations that their female corps were seldom fully militarized or under military discipline, that some had no women officers and were unsupervised as to housing or conduct; that in others women officers were chiefly traveling secretaries of male commanders, and that at least one corps had practiced mass recruitment of native women, whose unsanitary appearance and conduct in WAC uniform had played a part in bringing on the rumors that had

crippled recruiting. The Director's position was still further weakened when The Quartermaster General found that the large stocks of surplus winter uniforms, chiefly mismatched discards, could not be dyed successfully without wadding and shrinking. Reports from overseas areas indicated that in most cases unchanged uniforms had been acquired by local action. The problem appeared one not likely to be resolved until the application of selective service to women should have made public opinion of "WAC" conduct no longer a factor in recruiting costs. 77

[542]

Page Created August 23 2002