CHAPTER I

PRELUDE TO OCCUPATION

From Melbourne, five thousand miles away1 at the bottom of the world, General MacArthur by mid-1945 had smashed his way back to the very outposts of the Japanese homeland itself: Buna, Biak, the Philippine Sea, Leyte-a tremendous itinerary of two and a half years against a fanatically resisting foe.

At the end of June, he paused to assemble his forces, grown from scattered, relatively green American troops2 and a small but battle-hardened section of Australians, into a mighty concentration of power.3 On the ground, in the air, and on the sea they were massing for what would be the final drive against the Japanese stronghold, the homeland archipelago.4

Enemy resistance was to be pulverized in an invasion drive that would begin in the fall of 1945 and be continued in a second phase in the spring of 1946. Operation "Olympic" would launch an amphibious assault by veteran Sixth Army troops against southern Kyushu to secure the needed beachhead.5 Tremendous hammer blows by air and sea would soften up the formidable objective before the troops went in. Then, in Operation "Coronet," three corps including eight divisions of the Eighth Army, and two more corps of the First Army would be catapulted into the heart of the Tokyo Plain itself.

It was expected to be costly.6 The enemy would be fighting in prepared positions. He would be fighting for his home, his family. He had nothing to gain by surrender, everything to lose by defeat.

The much publicized " invincibility " of the Nipponese soldier had been blasted, however, during the long campaign that started over the Kokoda Trail and had now reached a point within easy flight range of Tokyo. He bled and died like any other mortal, but of

[1]

late it had been found that he would surrender.7 Could it be that other tales of the seemingly immovable determination of the Japanese people from the lowest coolie to the Emperor himself, likewise had a basis more of propaganda than of fact? In other words, could there be a sudden collapse? Or even a total surrender of the Japanese military forces before the scheduled launching by General MacArthur of that final, costly drive into the very heart of the homeland ? Every contingency had to be provided for.

While operations "Olympic" and "Coronet" delineated the vast concept of occupation by force, another plan just as complete and arranged for easy conversion from the basic concepts of "Olympic" and "Coronet," emerged from the Staff planning precincts of General Headquarters : this was Operation "Blacklist," General MacArthur's proposal to meet that other possibility, the sudden collapse or surrender of the Japanese Government and High Command. (Plate No. 1)

Operation "Blacklist" made its official but guarded appearance in top commands in July 1945; actually, it had been in the making since May of that year.8

The first edition was published 16 July and was presented four days later at a conference with ranking service representatives of the Pacific Ocean Areas at Guam.9 General MacArthur based his plans on the assumption that it would be his responsibility to impose surrender terms upon all elements of the Japanese military forces within Japan, and that he would also be responsible for coordinating and enforcing upon the Japanese Government and High Command the demands of Allied commanders in other areas.

Operation "Blacklist" called for the progressive occupation of fourteen major areas in Japan and from three to six areas in Korea so that Allied forces could exert undisputed military, economic, and political control. These operations would employ twenty-two divisions and two regimental combat teams in addition to air and naval elements, utilizing all of the U. S. forces available in the Pacific Theater at the time. Additional forces from outside the theater would be required if occupation duties were to be assumed in Formosa or in China.

Operation "Blacklist" provided for maximum but discreet use of existing Japanese political and military organizations. These agencies still had effective control of the population, and they probably could be employed to advantage by the Allies. If the existing governmental machinery were swept away, the difficulties of control would be enormously multiplied and additional occupation forces would be needed.10 The language

[2]

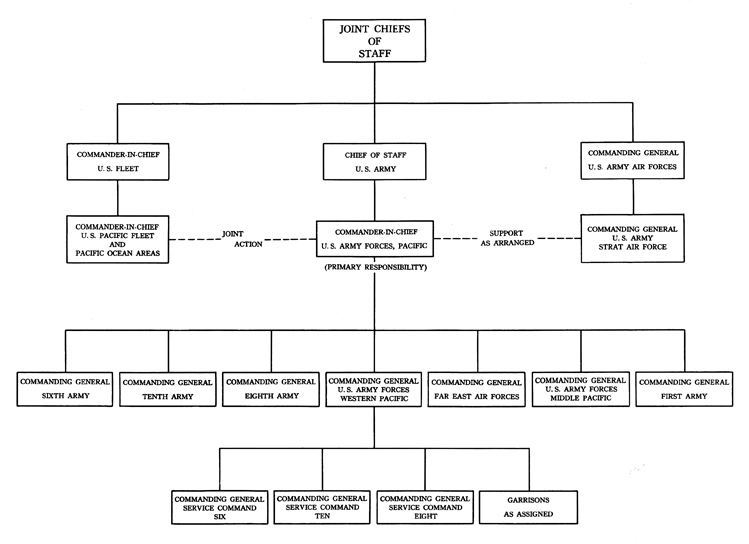

PLATE NO. 1

Organization of U.S. Army Forces, Pacific, for "Blacklist" Operations, July 1945

[3]

barrier alone represented an effective bar to administration.

A preliminary directive of the Joint Chiefs of Staff conformed generally to a collateral staff study prepared by Pacific Fleet Headquarters under the code term "Campus".11 That study provided for entry into Japan by United States Army forces only after the Navy had made an emergency occupation of Tokyo and had completely deployed occupation forces in the principal parts. General MacArthur agreed that immediately after capitulation the United States Fleet should move forward, seize control of Japan's home waters, take positions in critical localities, and begin minesweeping operations, but this was considered to be merely a prelude for landings by strong, coordinated ground and air forces of the Army, prepared to overcome any possible opposition.

General MacArthur considered that naval forces were hardly designed to effect the occupation of an enemy country whose army was still in existence; the occupation should rather proceed along sound tactical lines, with each branch of the service performing its appropriate mission. General MacArthur objected to major reliance on airborne landings because they involved what he considered to be unwarranted hazards. He saw no reason for hasty or rash action. Occupation by a weak force might encourage local opposition, with serious repercussions among the bomb-shattered population.12 It was estimated that there would be in excess of 1,700,000 regular combat servicemen to be disarmed in Japan proper and more than 3,200,000 civilian defense volunteers. In Korea about 270,000 regulars could be expected, while 35,000 civilian volunteers likewise would have to be disarmed.13

Concept of Operations : "Blacklist"

It was a basic policy in "Blacklist" to delegate authority and responsibility to designated army commanders and their corresponding naval task force commanders to the greatest extent consistent with central coordination by General Headquarters. However, the plan left nothing to chance. It could be assumed that at best there would be an attitude of non-cooperation in Japan and at worst, armed resistance in many parts of the main islands, despite such proclamations for the cessation of hostilities as would be required of the Emperor.14 Consequently, the commitment of forces was stipulated to be sufficient to reduce completely any local opposition, to establish bases at the strategic points outlined, to seize control of the higher echelons of government in both Japan and Korea, and to immobilize the armed forces of Japan. It was planned to organize these strategic centers with utmost speed in order to make them service bases from which air and ground action could be brought to bear wherever the exigencies of the situation might require.

Second priority for occupation would be restricted to strategic points to establish control of remaining major political centers and avenues of sea communications.

A third priority for occupation would be concerned with areas for the establishment of control of food supply and of principal overland and coastwise communications.

[4]

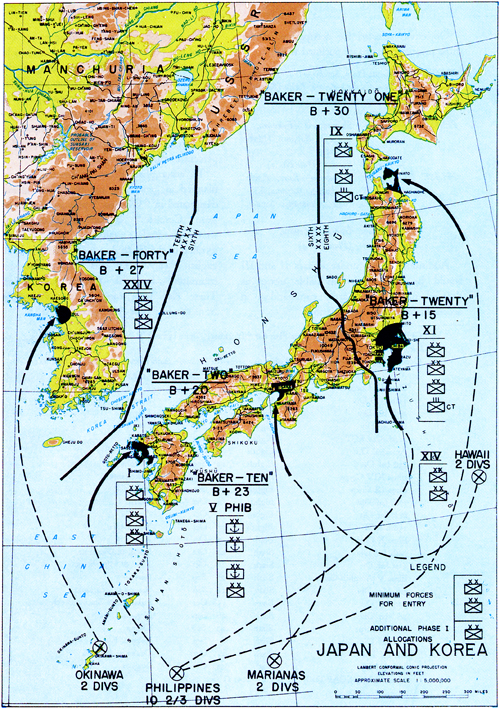

PLATE NO. 2

"Blacklist" : Concept of Phase I Operations

[5]

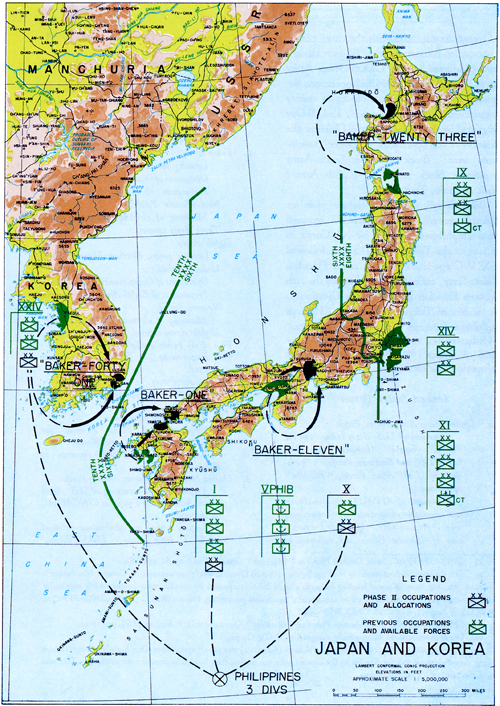

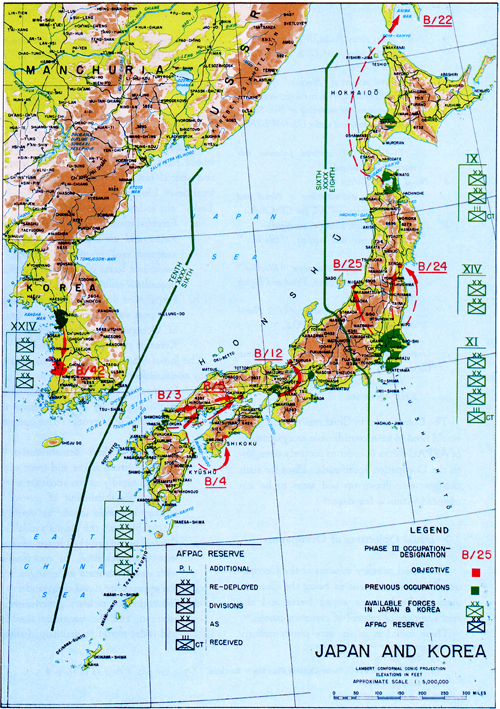

Objectives selected for occupation in the three priorities or phases outlined were:15

| PHASE I | -Kanto Plain, Sasebo | -Nagasaki, Kobe-Osaka-Kyoto, Keijo (Korea), Aomori, Ominato.

|

| PHASE II | -Japan: | Shimonoseki-Fukuoka, Nagoya, Sapporo (Hokkaido). |

-Korea:

|

Fusan. (Plate No. 3)

|

|

| PHASE III | -Japan: | Hiroshima-Kure, Kochi (Shikoku), Okayama, Tsuruga, Otomari, Sendai, Niigata. |

| -Korea | Gunsan-Zenshu. (Plate No. 4) |

Additional points under Phases II and III would be occupied by available troops as deemed necessary by army commanders in accomplishment of their missions.

The directed occupations would permit control of the political, economic, and military life of the two countries. The areas designated in Japan included 60 percent of the population, 80 percent of the industrial capacity and 48 percent of the food production. Those in Korea included 39 percent of the population, 18 percent of the industrial capacity, and 44 percent of the food production.

To accomplish Phase I objectives, it was planned in general to use the forces already designated in "Olympic" plus some elements from "Coronet." A total of 644,000 troops were earmarked as available. These included 251,800 of the Sixth Army and 308,700 of the Eighth Army.16 (Of this total 83,500 were committed for the Korean Occupation.) There also were roughly 62,000 available from the Far East Air Forces (FEAF).17

[6]

Operations to accomplish the three phases of occupation constituted the "B" or "Baker" series conducted by the United States Army Forces, Pacific, with individual operations designated by numbers within blocks of twenty assigned each Army concerned, and B-Day designated by the Commander in Chief for the initiation of the operations. "Baker" assignments were : Block 1 to 20, Sixth Army operations; Block 20 to 40, Eighth Army; Block 40 to 60, Tenth Army.18

"Baker-Sixty" was the alternate plan for "Baker-Twenty." "Baker-Twenty" required initial amphibious landings by XI Corps in the area of the Tokyo Plain (Kanto), followed by XIV Corps landings in northern Honshu. " Baker-Sixty" called for air landings by the 11th Airborne Division and the 27th Division in the vicinity of Tokyo, followed by XI Corps amphibious landings in the Tokyo Bay area.19

Utilization of the total forces at the command of General MacArthur to effect the Occupation was established as follows:20

United States Forces

a. United States Army Forces, Pacific

Command of U.S. Army resources in the Pacific. (Except Alaskan Department, USASTAF and Southeast Pacific). Operations of U. S. Army Forces, "Blacklist " operations.

Command of AFPAC Occupation Forces and imposition of surrender terms in assigned areas of responsibility. Approval of repatriation of Japanese Forces and nationals to Japan proper. Theater Command, SWPA.

1. Sixth Army

Landing forces, Kyushu, Shikoku, Western Honshu area.

Operations of Occupation Forces, same area.

Preparation of Sixth Army elements from Western Pacific.

Mounting of elements transported under Sixth Army control.

2. Tenth Army21

Landing forces, Korea.

Operations of Occupation Forces, same area.

Preparation of Tenth Army elements from Western Pacific.

Mounting of elements transported under Tenth Army control.

3. Eighth Army

Landing forces, Northern Honshu, Hokkaido, Karafuto.22

Operations of Occupation Forces, same area.

Preparation of Eighth Army elements from Western Pacific.

Mounting of elements transported under

Eighth Army control.

4. First Army (when available)

Preparations for further operations as directed.

5. Far East Air Forces

Land-based air support, "Blacklist" operations.

Troop carrier operations.

Preparation of FEAF elements for displacement to Japan and Korea.

Establishment of FEAF elements in designated locations.

6. United States Army Forces, Middle Pacific

Preparation and mounting of U.S. Army Forces from Middle Pacific for CINCAFPAC as directed.

Logistic support and administrative control of U. S. Army Forces in Middle Pacific.

[7]

PLATE NO. 3

"Blacklist" : Concept of Phase II Operations

[8]

PLATE NO. 4

"Blacklist" : Concept of Phase III Operations

[9]

7. United States Army Forces, Western Pacific

Logistic support of U. S. Army Forces, Western Pacific.

Logistic support of "Blacklist" operations. U.S. Garrisons, Western Pacific, as directed.

Preparation and mounting of Base Service elements transported under USAFWESPAC control.

Disposition of captured Japanese war material as directed.

8. Naval Forces, SWPA

Preparation and mounting of Naval and Marine elements, SWPA, for CINCPAC.

b. United States Pacific Fleet (as arranged)

Naval cover and support, "Blacklist" operations.

Naval and amphibious phase, "Blacklist" operations, including Sixth, Tenth and Eighth Army operations.

Preparation and mounting of U.S. Naval and Marine elements from POA.

Theater Command, POA.

c. United States Army Strategic Air Force (as arranged)

Transport of troops by air as arranged.

VHB operations.

The Commander in Chief realized that there would need to be a considerable reorganization of AFPAC forces in order to properly strengthen the Occupation spearheads. Plans for such changes were drawn up and were to be announced within a few days.23

Initial Objectives of Occupation

The initial primary missions of the Occupation forces were set out as being the disarmament of the Japanese armed forces and the establishment of control of communications.24

These initial missions were purely military in character. From that point on, there would inevitably be a progressive fusion of the military with civil and political aspects of the nation which would also become the responsibility of the Commander in Chief. For some months, however, control would probably be direct and rigid. Accordingly, it was designated in the plan that army commanders would have assigned to them certain general and special tasks common to all occupation localities.25 Under the heading of "General Tasks" the following were outlined:

a. Establishment of control of the armed forces and civil population in areas assigned and imposition thereon of prescribed terms of surrender requiring immediate military action.

b. Preparation for establishment of separate post-war governments and armies of Occupation in Japan Proper and Korea as subsequently directed.

The initial "Special Tasks" envisioned for army commanders were as follows:

a. Destruction of hostile elements which might oppose by military action the imposition of surrender terms upon the Japanese.

b. Disarmament and demobilization of Japanese armed forces and their auxiliaries as rapidly as the situation would permit. Establishment of control of military resources insofar as would be practicable with the means available.

c. Control of the principal routes of coast-wise communication, in coordination with naval elements as arranged with the appropriate naval commander.

d. Institution of military government, if required, and the insurance that law and order would be maintained among

[10]

the civilian population. Facilitation of peaceful commerce, particularly that which would contribute to the subsistence, clothing and shelter of the population.

e. Recovery, relief, and repatriation of Allied prisoners of war and civilian internees without delay.

f. The securing and safeguarding of intelligence information of value to the United States and Allied Nations. Arrangement with the U. S. Navy for mutual interchange and unrestricted access by each Service to matters of interest thereto.

g. Suppression of activities of individuals and organizations inimical to the operations of the Occupation forces. Apprehension of war criminals, as directed.

h. Support of elements of the initial Occupation forces in the occupation of subsequent objectives, as directed.

i. Preparation for the imposition of terms of surrender beyond immediate military requirements.

j. Preparation for the extension of control over the Japanese as required to implement policies for post-war occupation and government, when prescribed.

k. Preparation for the transfer of responsibilities to agencies of the post-war governments and armies of occupation, when established.

Army commanders would issue their own detailed orders for the accomplishment of these general and special tasks. The orders would cover such matters as the safeguarding of captured enemy combat materials, including documents, the proper securing of industrial properties against damage, and the preservation of public utilities.26 It was emphasized that in view of the limited forces which would have to occupy a country of roughly eighty millions, army commanders would make all possible use of Japanese demobilized forces within the bounds of security, and would take all steps to insure that public servants, such as the civil police, railway workers, communication workers, utilities operators and public health officials, not only remained at their tasks but intensified their efforts to insure a continuation of all functions under what was certain to be a period of great stress.27 It was imperative that discipline should be maintained, both among the armed forces of Japan and the civil population. Accordingly, provisions for enforcing the requirements of the Occupation authorities were made; these were strictly in accordance with the established rules of land warfare, and were so specified.28 Looting by Occupation forces and all other forms of violence against the habitants of the country were expressly forbidden.

General Headquarters was prepared to press the final act-occupation by force, or occupation by acquiescence.

Which would it be: Operation "Olympic" or Operation "Blacklist"?

The possibility of surrender now was openly discussed in the world's capitals. On 27 July the Allied Powers called upon the Japanese

[11]

Government through the Potsdam Declaration to cease the struggle, to throw out militarism and to invite the establishment of democratic processes under the direction of an Allied Commander in Chief to be named.

Tokyo was silent and remained silent. Apparently it would be "Olympic."

Then came 0800 of 6 August 1945 and the first atomic bomb unleashed against an inhabited place.29 Three days later the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics declared war against the staggering empire. On the same day the second atomic bomb was dropped, this time against Nagasaki.

Stunned by these developments, and well aware that continued large-scale resistance would be impossible, the Japanese Government indicated receptiveness to the terms of the Potsdam Declaration.

General MacArthur shifted quickly to meet probable exigencies. He alerted Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger of the Eighth Army, Gen. Walter Krueger of the Sixth, Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell of the Tenth, and Lt. Gen. John R. Hodge of the XXIV Corps to hold their commands in readiness for the Occupation of Korea and Japan; in other words, to be prepared for the immediate implementation of " Blacklist," as somewhat augmented by a new edition put into the hands of Army commanders early in August.30

President Truman announced on 15 August the unconditional surrender by the Japanese Imperial Government. On the same day, General MacArthur was named Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and was charged with taking all steps he deemed necessary and proper to effectuate the surrender terms with the least practicable delay.31

Simultaneously on that date two vital directives emanated from headquarters of the Supreme Commander in Manila. One cancelled Operation "Olympic" and ordered implementation of the initial phases of Operation "Blacklist." The other ordered the Emperor to take immediate effective steps for the cessation of hostilities and for the opening of radio communications between Manila and Tokyo.32 With regard to the latter, exasperating and suspicious delays occurred and it was some days before a reliable channel was established. As soon as this was done, however, General MacArthur radioed a demand for the dispatch to Manila of a responsible Imperial Mission with full powers to receive details of the terms of surrender and to provide GHQ with pertinent information which would secure the safety of Allied prisoners of war, and eliminate any capability to resist occupation forces.33

Simultaneously with the order to implement Blacklist," SCAP initiated a thorough re-

[12]

Gen. Walter Krueger Sixth U.S. Army 1943-1946 |

Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger Eighth U.S. Army 1944-1948 |

Vice Adm. R. M. Griffin Naval Forces Far East 1946-1948 |

Gen. Ennis C. Whitehead Far East Air Forces 1945-1949 |

PLATE NO. 5

Senior Commanders of the Occupation Forces

[13]

organization of AFPAC forces to provide strength where it would be most needed by the Sixth and Eighth Armies and the XXIV Corps (then with the Tenth Army in the Ryukyus).34

The 11th Airborne Division had already passed to the control of the Commanding General of the Eighth Army, and had moved by air with full combat equipment from Lipa in Luzon to Okinawa, in a record time of forty-four hours. The Division was preparing to spearhead the invasion forces. Four days later, certain additional adjustments were made. The Eighth Army, which would occupy Japan alone from 28 August to 22 September, was given the IX and XI Corps, in addition to the XIV Corps which it already controlled.35 The Sixth Army was increased primarily by the addition of the V Amphibious Corps, with its 2d, 3d and 5th Marine Divisions, located in Saipan, Oahu, Guam and Hawaii. General Krueger, Commanding the Sixth Army, also assumed control of the X Corps, the 6th Division from the Eighth Army, and the 98th Division from AFMIDPAC. Simultaneously, control of both these divisions passed to I Corps, already under the Sixth Army.

Control of the XXIV Corps on Okinawa passed from the Tenth Army to AFPAC, because it was to operate independently as the Occupation force in Korea south of the 38° parallel.

The total U. S. land and air forces now available to the Commander in Chief for Occupation operations and all other responsibilities in his area of command were as follows:36

(1) Sixth U. S. Army

Gen. Walter Krueger, U. S. Army

I and X Corps and V Amphibious Corps

(Marine)

6th, 24th, 25th, 33d, 41st and 98th Divisions, 2d, 3d and 5th Marine Divisions

(2) Eighth U.S. Army

Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, U. S. Army

IX, XI and XIV Corps

27th, 43d, 77th, 81st and Americal Divisions, 1st Cavalry Division, 11th Airborne Division, 112th Cavalry RCT, 158 1nfantry RCT.

(3) XXIV Corps

Lt. Gen. John R. Hodge, U. S. Army

7th, 96th and 40th Divisions.

(4) Tenth U. S. Army

Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, U. S. Army

As constituted.

(5) First U. S. Army

Gen. Courtney B. Hodges, U. S. Army

As later constituted.

(6) Far East Air Forces

Gen. George C. Kenney, U. S. Army

5th, 7th and 13th Air Forces.

(7) United States Army Forces Middle Pacific

Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, U. S. Army

As constituted.

(8) United States Army Forces Western Pacific

Lt. Gen. Wilhelm D. Styer, U. S. Army

As constituted.

General MacArthur assigned the responsibility for the security of the Ryukyus to ASCOM-I and directed AFWESPAC to assume combat responsibilities in the Southwest Pacific Area. The Commanding General of AFWESPAC established two commands to maintain security in the Philippines: the Luzon Area Command and the Southern Islands Area Command.

A recapitulation as of 15 August of the strength of combat and service troops committed exclusively to the Japan and Korea Occupa-

[14]

Adm. William F. Halsey Third U.S. Fleet |

Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid Seventh U.S. Fleet |

Adm. Raymond A. Spruance Fifth U.S. Fleet |

Vice Adm. Frank J. Fletcher North Pacific Force |

PLATE NO. 6

U.S.N. Fleet Commanders at the Beginning of the Occupation

[15]

tion operations was as follows:37

XXIV Corps:

A. |

Combat |

62,724 |

|

B. |

Service |

29,076 |

|

Total XXIV Corps |

|

91,800 |

|

Sixth U. S. Army |

|

|

|

A. Combat |

122,355 |

|

|

B. Service |

63,551 |

|

|

C. V Amphibious |

93,522 |

|

|

Total Sixth U. S. Army |

|

279,428 |

|

Eighth U. S. Army: |

|

|

|

A. Combat |

156,691 |

|

|

B. Service |

90,052 |

|

|

Total Eighth U. S. Army |

|

246,743 |

|

Far East Air Forces |

10,669 |

|

|

A. |

XXIV Corps Zone |

|

|

B. |

Sixth Army Zone |

35, 6 54 |

|

C. |

Eighth Army Zone |

42,810 |

|

|

Total Far East Air Forces |

|

89,133 |

| Grand total for the operation ......................................................... | 707,104 | ||

Air Corps units, exclusive of service elements, which might be called upon to sustain the operations either in combat or troop transportation missions and which were located within respective zones of responsibility were as follows:38

XXIV Corps : 475th Fighter Groups and squadron of 317th Troop Carrier Group.

Sixth Army: Eighth and 348th Fighter Groups, the 375th and 443d Troop Carrier Groups and the Second Combat Cargo Group.

Army and Corps commanders were directed to organize Army service commands from troops to be made available to them from organizations envisioned for "Olympic" and "Coronet" operations.39 The Commanding General of Sixth Army was to establish Army Service Command "O" (from "Olympic") and General Eichelberger's Eighth Army was to be supplied and serviced by a similar unit, "C" (from "Coronet").40

The Commanding General, AFWESPAC, was directed to release men and materials for these purposes as rapidly as possible.41

[16]

The Eighth Army was to lead the Occupation forces into Japan and was directed to execute "Baker 60".42 This called for air landings in the vicinity of Tokyo by the 11th Airborne Division and the 27th Division (if required), followed by IX Corps amphibious landings in the Tokyo Bay area. The seaborne troops for Japan and Korea were scheduled to begin arriving after the formal surrender ceremony aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, but the airhead would be secured by the 11th Airborne three days before the ceremony. The 27th Division had been alerted for airlift from the Ryukyus. The 4th Marine Regimental Combat Team (the Fleet Landing Force), was to occupy Yokosuka Naval Base, south of Yokohama, at the same time the 11th Airborne units were to establish their positions near Tokyo.43

Upon the Fifth Air Force would fall the chief responsibility for the tremendous air movements. To assist the Fifth Air Force, the Strategic Air Force was to release heavy bombers to the operational control of FEAF as requested by the latter. Strategic Air Force was also charged with dropping of food and supplies to prisoners of war and civilian internee camps. The Air Transport Command was to lend the bulk of its carrier planes as requested by FEAF and assigned by FEAF to Fifth Air Force. As aircraft which would carry in Occupation forces were turned around, they would be loaded with repatriated Allied prisoners of war requiring hospitalization. In addition, FEAF was charged with continuing its regular tasks of reconnaissance and photographing of Japan and Korea to facilitate the implementation of "Baker 60 ". A tentative series of "strategic" flights would be stepped up in frequency and size to constitute a show of force to discourage possible plots on the part of recalcitrants. These flights would be restricted to critical areas south of 38 ° north. The U. S. Pacific Fleet was to provide air protection for naval forces, convoys and shipping.

The Thirteenth Air Force was to take over the Philippines area of responsibility, while the Seventh was to support the Tenth U.S. Army operations in the Ryukyus. The RAAF Command would continue to operate in the southern areas, particularly the Netherlands East Indies. Aircraft of the Seventh Fleet as well as Eighty-fifth Fighter Wing of the Air Defense Command would continue to operate in the Philippines area.44

The U. S. Pacific Fleet would be charged with the establishment of military government in the Marianas, Bonin, Volcano, Izu, and Kurile Islands and on Marcus Island.45 At the same time it would have the responsibility for conducting the naval and amphibious phases of the occupation of Japanese territory by the United States Army Forces, Pacific. This would include provision of destroyer station ships along the entire convoy route from Okinawa to Honshu. The Third U. S. Fleet, under command of Admiral William F. Halsey, was to occupy Tokyo Bay and support Eighth Army landings. As has been stated, the USS Missouri of the Third Fleet, flying the pennant of Admiral Chester Nimitz, was to become the scene of the formal surrender ceremonies.46

The Fifth Fleet, under the command of Admiral Raymond Spruance, was to occupy and patrol sea approaches and coastal waters of Japan west of 135 degrees. Eventually it was to land elements of the Sixth Army in Kyushu, Shikoku, and western Honshu.

The Seventh Fleet, under command of Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, was to be held to

[17]

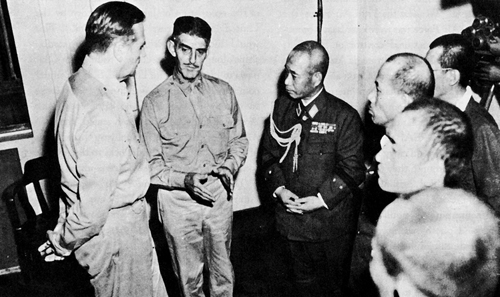

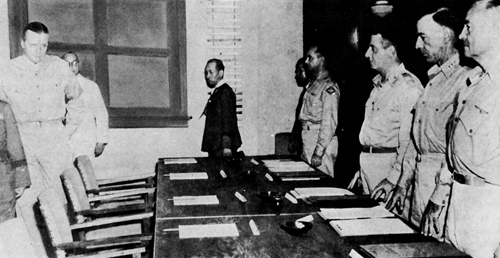

The Japanese delegation arrives at Nichols Field, 19 August 1945

Col. S. Mashbir, Chief, Allied Translator and Interpreter Service (ATIS),

G-2, acts as interpreter during a pre-conference interval.

PLATE NO. 7

Surrender Negotiations at Manila

[18]

assist in staging, training, and mounting troops for the control of the coastal waters of China and Korea.48

The North Pacific Force, under Vice Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, was to be loaned for mine-sweeping operations between Honshu and Hokkaido.49

As had been the practice throughout the war in the Pacific, units of the British Commonwealth naval strength, particularly Australian ships which had distinguished themselves by their splendid war record with the American fleets, would be included in these critical Occupation operations.

Return of Surrender Delegation

from Manila

Details for initial moves for the Occupation of Japan were outlined to the Imperial delegates which had arrived at Manila 19 August and had been in session with GHQ staff officers that and the succeeding day.50 When they departed again for Tokyo, they carried with them four documents which outlined the requirements laid down by SCAP for the spearhead off occupation, for the formal surrender ceremonies, and for the subsequent reception of Occupation forces.51

In these documents SCAP stated that the acceptance of the surrender of the Japanese armed forces would occur in Tokyo Bay aboard a United States battleship on 31 August. To prepare for this, he indicated that an advance party would arrive by air at Atsugi airdrome near Tokyo, that United States Navy forces would arrive in Sagami Bay, immediately south of Tokyo Bay, and that naval forces would advance into Tokyo Bay. These movements were set for 26 August. Airborne forces accompanying the Supreme Commander were expected to land at Atsugi 28 August while, simultaneously, naval and marine forces were to land in the vicinity of Yokosuka Naval Base. The landing and establishing of airborne and naval forces would continue during the two days prior to the surrender ceremony.

The second document concerned the advance landing party and its point of entry. It specified that the immediate area surrounding the city of Tokyo was defined as the "Tokyo Bay Area."52 This area comprised the region from Choshi north of Kumagawa, east of Ishioka, and southeast to Choshi. The boundary across the harbor entrance included the island of Nishima. Within the Tokyo Bay Area the portion from Otsuki eastward along the southern city limit line and extending across the Bay to Chiba and south of Amatsu, was defined as the "Area of Initial Evacuation." (Plate

[19]

Conference for terms of Surrender opens. L to R, on the Japanese side, Capt. H. Yoshida,

Capt. T. Ohmae, Rear Adm. I. Yokoyama, Lt. Gen. T. Kawabe, Mr. Ko. Okazaki, Maj.

Gen. M. Amano, and Lt. Col. M. Matsuda; on the American side, Maj. Gen. L. J.

Whitlock, Maj. Gen. R. J. Marshall, Rear Adm. F. P. Sherman, Lt. Gen. R. K. Sutherland,

Maj. Gen. S. J. Chamberlin, Maj. Gen. C. A. Willoughby and Brig. Gen. D. R. Hutchinson.

Escorted by General Willoughby, the Japanese delegation arrives for conference. Ranking

American officers await: Brig Gen. D. R. Hutchinson, Maj. Gen. S. J. Chamberlin, Maj.

Gen. R. K. Sutherland, and Rear Adm. F. P. Sherman, representing Admiral Nimitz.

PLATE NO. 8

Surrender Negotiations at Manila

[20]

No. 9)

The advance party would make preparations for the entry of the Supreme Commander and his accompanying airborne and naval forces into the Area of Initial Evacuation. The Japanese Imperial General Headquarters would be required to acknowledge to the Supreme Commander by 25 August safe conduct for the advance party which was to consist of about 150 persons, transported in planes with standard U. S. markings. This party was scheduled to land at Atsugi airfield. The Japanese would be required to provide for the following: security and preservation from harm of personnel, airplanes and equipment of the party while in the Area of Initial Evacuation; provision of every courtesy and facility to members of the party in the accomplishment of their mission; provision for suitable quarters and a police escort to insure absolute safety for each member of the party; the services of senior officers from the Japanese Army Air Headquarters, the Naval Air Headquarters, and the Japanese Army and Naval Headquarters, available to the commander of the advance party upon his arrival at Atsugi and prepared to provide such information as might be required as to facilities in the Area of Initial Evacuation; free communication by radio between the advance party and the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Manila.

The Japanese Imperial General Headquarters was to evacuate all combatant units of the Japanese armed forces from the Atsugi airfield area, with the exception of civil police, which were to be maintained as necessary to prevent overt acts. The airdrome was to be in full operational condition. Notification would be required prior to 25 August as to the identity and frequency of the radio station in the Tokyo area with which the advance party could communicate in flight concerning time of arrival, landing instructions and other matters relating to the arrival of the party.

The third document, in addition to providing for the immobilizing and disarming of Japanese naval and air force units and installations, required provision for the safety of the United Nations prisoners of war and civilian internees pending the arrival of Occupation forces.53 Camps were to be marked to enable Allied aircraft to identify them. The Yokosuka Naval Base was to be ready for occupation by 27 August. All combatant units of the Japanese armed forces were to be evacuated from the Area of Initial Evacuation and confined to the limits of their assigned bivouacs, with the exception of civil police; measures were to be guaranteed for the provision of adequate accommodations, billet and camp area facilities and utilities in the Area of Initial Occupation for the Supreme Commander and his accompanying forces.

It was directed that on the date scheduled for the arrival of General MacArthur in Japan, members of the Imperial General Staff would be available for conference with representatives of the Supreme Commander at Atsugi airfield upon arrival, and at such times and places thereafter as might be directed for the prompt settlement of all matters requiring attention. Guides and interpreters familiar with the Area of Initial Evacuation would be available.

General measures to be taken by 25 August by the forces of the Allied Powers were announced as follows: Allied aircraft would conduct daylight and night surveillance flights over Japan and Japanese controlled areas; Allied aircraft would drop supplies to the United Nations prisoner of war and internee camps; naval forces would occupy the coastal waters of

[21]

PLATE NO. 9

"Blacklist" : Area of Initial Evacuation and Withdrawal of Major Japanese Units

[22]

Japan and Japanese controlled areas. Mine-sweeping operations by Allied naval forces were scheduled to be initiated in the ports of Osaka. Sasebo, Nagasaki, Takasu, Jinsen, Tsingtao, Canton, Shanghai, Hongkong, and Singapore. In these prescribed duties, the Allied forces would be unmolested.

The fourth document concerned the initial Occupation forces in the Kanoya Area of southern Kyushu.54 It stipulated that an advance party, representing General Headquarters, would enter the area 1 September to prepare for the entry into the "Kanoya Area" of seaborne and airborne initial forces on the next day. The Japanese Imperial General Headquarters was directed to provide, by noon 30 August, guarantee of full security for entry into the Kanoya area of this advance party, consisting of twenty personnel, transported in two airplanes bearing standard U. S. markings. Exact time of arrival would be communicated to Kanoya radio station by direct message from the planes in flight. Ranking members of Japanese staffs were to hold themselves in readiness for conferences with high ranking American officers landing at Kanoya airfield.

The return to Tokyo of the Manila envoys was delayed when one of the planes carrying the principals experienced engine trouble and had to be "ditched." The pilot was able to beach the plane so that, although all passengers were shaken up, none was hurt. It required most of the night, however, to arrange transportation to Tokyo and this interval was marked by considerable anxiety.55 Prime Minister Prince Higashi Kuni sat up all night wondering "whether 'our invigorated Tokko Tai' (air attack units) had shot them down." If he was glad to hear that both planes were safe, he was far happier to learn that General MacArthur's terms for his nation were not so severe as he had feared.56

Higashi Kuni promptly took General Kawabe to the palace to make "a very minute report." According to Higashi Kuni, "The Emperor was quite relieved."57

General MacArthur's humane and considerate occupation policies unquestionably took Japan by complete surprise.58 A Domei broadcast, 18 August, stating that the Allies had no intention of confiscating private property, reassured Japanese who had feared that Americans would follow the Japanese policy of looting civilian goods.

Immediately following the Emperor's surrender proclamation, officials of the Agriculture-Commerce Ministry and the Chief of the Tokyo Economics board estimated that Japan's food supplies would be entirely dislocated because of expected heavy food requisitions by Occupation forces. Yomiuri-Hochi warned that the food requirements of the "tens of thousands" of Occupation troops would have a "great effect upon our present and future livelihood."59

When Japanese armies invaded foreign lands, the conquered populations, despite their poverty, had been expected to furnish not only full but even luxurious provisions for the invaders. Japan consequently looked upon General MacArthur as the precursor of a truly enlightened civilization.

Confidence in General MacArthur's justice went far toward reassuring Japanese who still credited pure wartime propaganda rumors.60

[23]

Tokyo Shimbun, among others, deplored that wild gossip swept Japan. Of this kind Yomiuri reported: .... within three days after surrender Tokyo citizens feared that:

American soldiers would loot Japan.

Americans would rob Japan of all the food.

Women and girls would be violated.

All men would be killed.

What was left of Tokyo would be devastated.61

The American decision to reserve all Japanese food resources for the Japanese people and to supply the Occupation forces and their dependents with foodstuffs brought from America therefore produced a profound, completely unexpected, and highly favorable impression.62

During the next few days, while Japanese people were attempting to adjust their thinking to this new concept of enemy occupation, the weather became unfavorable and a series of typhoons lashed the home islands; nevertheless, the people heard the drone of Allied aircraft overhead and from force of habit ran to their air raid shelters. There were no bombs; instead, this was the beginning of the air force missions to drop relief supplies of food, medicine and clothing to the wretched Allied prisoners of war and civilians interned in camps in Japan. The missions continued despite extremely unfavorable weather which became sufficiently adverse to delay the implementation of "Blacklist" by forty-eight hours.

Implementation of Operations:

"Blacklist "

General Eichelberger had moved his Eighth Army Command Post from the eastern coastal plain of Leyte to Okinawa on 26 August. On Okinawa both the 11th Airborne and the 27th Division were stalled on the scheduled airlift to Japan by the succession of typhoons.

All available troop transports of the Far East Air Force and dozens of the huge "Skytrains" and "Skymasters" of the Pacific Air Transport Command had been mobilized at Okinawa for this mammoth air operation-the greatest aerial movement during the Pacific war. The initial target date was officially postponed from 26 August to 28 August because of the adverse weather.63

Then the weather cleared and a cool, refreshing breeze, "very refreshing to the spirit," blew over the Kanto Plain.64

At Atsugi airfield near Tokyo, Japanese planes sat helplessly stripped of their propellers. A picked detachment of the Naval Security Corps, armed with clubs, guarded the Atsugi airfield where Lt. Gen. Seizo Arisue, Lt. Gen. Senichi Kamada, Captain Chuzaburo Yamazumi and Ken Tsurumi of the Foreign Office awaited the arrival of the American advance forces.

The heralds of that advance force, American Corsairs and Grummans, had appeared with the dawn of that historic day and continued to fly in strong formations over the entire Tokyo Bay and Atsugi area.

The first American formations flying from Okinawa were not expected until 0900, but half an hour earlier a twin-engined aircraft appeared in the skies from the south. It was a C-46 transport. The plane circled the field and then came in from the south to touch down upon the center runway at 0828. This plane was followed by fifteen others.65

From the leading plane debarked Colonel

[24]

Charles P. Tench, GSC, of the G-3 Section of GHQ, commanding the advance party.66 Waiting automobiles conveyed Colonel Tench and party to the Japanese reception group.

General Arisue stiffly saluted Colonel Tench and, after introductions, the group entered a tent in the center of the field. General Arisue offered food, but Colonel Tench who had brought his own rations, declined with thanks.

Colonel Tench explained that his party consisted of approximately 150 officers and men and that their directive from the Supreme Commander was divided into four main divisions. It was as follows:

a. Reconnaissance of the Atsugi airdrome area to determine its suitability for the airborne operation to follow.

b. Establishment of required air installations and supplies to support initial phases of the air operations in the area as provided by the Commanding General, FEAF.

c. Supervision and coordination of improvements required at the Atsugi airdrome.

d. Establishment of communications with GHQ, AFPAC, without delay and reporting on suitability or non-suitability of the Atsugi airdrome for the purpose intended. All messages to be transmitted in code. Reporting over signal communications net additional information desired by the Commanding General, FEAF.

While this initial conference took place, soldiers debouched from the planes coming to earth every few moments, unloaded jeeps, and prepared to form exploratory parties. Colonel Hutchinson, who had been assigned as billeting officer, led the first of these on an inspection of the former Sagamigahara Air Unit barracks at the west end of the airfield. It was proposed by the Japanese that this barracks should serve as accommodations for the advance party. Other inspection teams immediately deployed over the entire airfield area.

A second flight of fifteen C-54's, C-46's, and C-47's arrived at 0935 and a third group of fifteen C-54's landed at 1100. These planes, carrying a total of 30 officers and 120 men wearing regular combat equipment were escorted by ten carrier-based Seventh Fleet F6F liaison planes flying from Sagami Bay.

The Japanese were amazed by the efficiency with which these Grumman fighters, landing on the grass, folded their wings "like cicadas," even while the planes were taxied into position.67 The Japanese made no attempt to conceal the degree to which they were impressed by the speed with which the Americans motorized themselves and invested the entire field area. Their amazement was outspoken when within forty-five minutes after the leading planes had touched down, portable Signal Corps transmitters were on the air establishing communications with Okinawa. The last planes of the party brought fuel, lubricants, and maintenance equipment to make the intrepid little unit compact and self-sustaining until the anticipated arrival on 30 August of the main airborne force which would constitute the first of the Occupation troops for Japan.

While the air lift of the main initial force was in progress on 30 August, GHQ, AFPAC, issued an amendment to Operations Instruc-

[25]

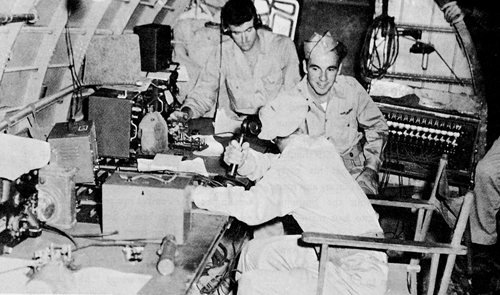

This communications plane served for three days as the only means of communication

between the advance party at Atsugi and headquarters on Okinawa and in Manila.

The advance party at Atsugi Airfield, 28 August 1945. Col. Charles P. Tench

is met by Lt. Gen. Seizo Arisue.

PLATE NO. 10

Pre-occupation Party Arrives in Japan

[26]

tions No. 4, which materially altered the missions assigned to the Army commanders who soon would be arriving on the Nippon homeland. Instead of actually instituting "military government," Army commanders were to supervise the execution of the policies relative to government functions which GHQ, AFPAC, was to issue directly to the Japanese Government;68 likewise the functions of the Armies with respect to the disarmament and demobilization of the Japanese armed forces were changed from "operational control" and direction to "supervision of the execution" of orders, as transmitted to the Japanese by GHQ, AFPAC. In contrast to the original concept the headquarters of the Japanese Government and its armed forces were required to shoulder the chief administrative and operational burden of disarmament and demobilization. The new plan was designed to avoid possible incidents which might result in a renewed conflict; no seizures or disarmaments were to be made by Allied personnel.69

Actually, with the arrival of the advance party, the toe-hold of occupation had been established. But less than 200 men with light weapons could hardly be described as constituting an occupation force in a country where three to four million soldiers of all classifications were still under arms, and as far as the Americans knew, were only precariously held in discipline by the proclamations of one man-the Emperor.

It was imperative that every effort be made to insure the early and safe arrival of the 11th Airborne force of some seven thousand men. An inspection of Atsugi revealed the necessity for the immediate construction of landing strips long enough to accommodate B-29s and C-54s which would be landing in rapid succession once the movement had started. Only one night could be devoted to this construction work involving strips one and one-half kilometers in length. Under the supervision of the small American force, the Japanese workmen recruited by the indefatigable General Arisue became efficient to a degree apparently never before experienced by the Japanese officers.70 With the break of dawn, the work was near enough to completion to enable the advance party to signal GHQ at Manila for relay to Okinawa that everything was in readiness for the initiation of the real Occupation of Japan-the first by a foreign army in the recorded history of that nation.71

[27]

Go to

Chapter II

Last updated 11 December 2006 |