CHAPTER III

THE COMMAND STRUCTURE: AFPAC, FEC AND SCAP

Establishment of AFPAC: Army

Forces in the Pacific

The conquest of the Philippines completed the principal mission of the Commander in Chief of the Southwest Pacific Area.

On 4 April 1945 a command directive was issued by the joint Chiefs of Staff for the guidance of commanders in the Pacific Theater. This directive stated that the over-all objective in the war against Japan was to be brought about at the earliest practicable date by establishing sea and air blockades, by conducting intensive air bombardments and destroying Japanese air and naval strength, and by invading and seizing objectives in the industrial heart of Japan. General MacArthur was designated as Commander in Chief, Army Forces in the Pacific, (CINCAFPAC) and all U. S. Army resources in the Pacific (less SE Pacific Area and Alaskan Department) were placed under his control.1

On 6 April, the War Department ordered the above consolidation:2

Effective at once U.S. Army Forces in the Pacific is established. Short title AFPAC. U.S. Army Forces in the Pacific will consist of those forces presently assigned U.S. Army Forces in POA. General of the Army MacArthur is designated Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Army Forces in the Pacific (CINCAFPAC), in addition to his present assignment. Transfer of forces will be accomplished in accordance with instructions issued by JCS already.

On the same day General MacArthur issued General Order Number 1, GHQ, AFPAC, which established AFPAC and placed it under his command. Four months later the Japanese surrendered.

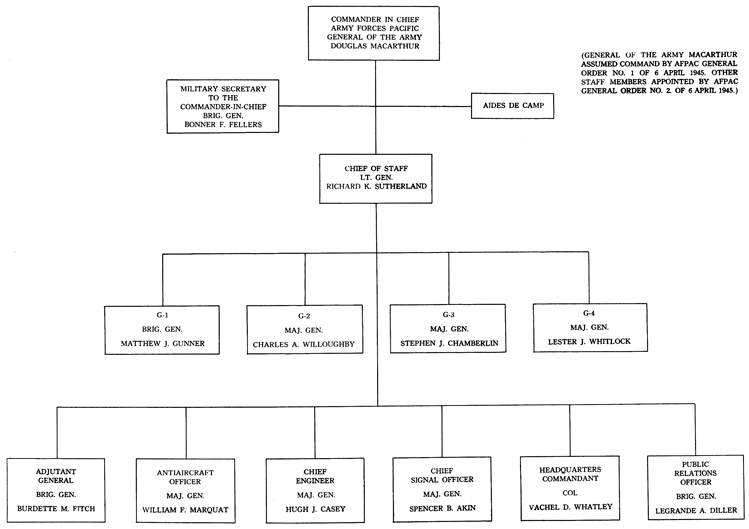

The command structure of AFPAC remained static throughout the initial phases of the Occupation and furnished the military background for the development of SCAP, the next evolutionary step in the high command. (Plate No. 23)

Establishment of SCAP: Supreme

Commander for the Allied Powers

At Potsdam in July of 1945, the heads of the governments of the United States and the United Kingdom agreed upon the terms of the surrender ultimatum to be offered Japan. Following this agreement, the Potsdam Declaration, concurred in by China and subsequently approved by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, was issued on 26 July. The Japanese capitulation proclamation included acceptance of the terms of this declaration.

On 14 August General MacArthur was designated "Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers" (SCAP) pursuant to an international agreement among the above four governments. This instrument accorded the General an extraordinary range of authority:3

[67]

PLATE NO. 23

Organization of General Headquarters, Army Forces in the Pacific, 6 April 1945

[68]

From the moment of surrender, the authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state will be subject to you and you will take such steps as you deem proper to effectuate the surrender terms.

You will exercise supreme command over all land, sea and air forces which may be allocated for enforcement in Japan of the surrender terms by the Allied Forces concerned.

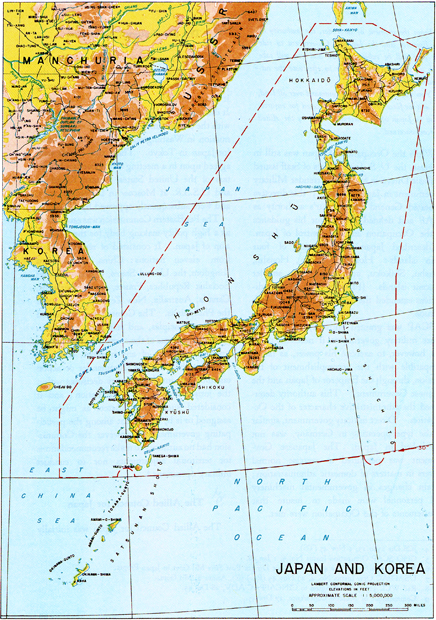

While the Occupation of Japan was still in progress, the U. S. Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a "Basic Directive for Post-Surrender Military Government in Japan Proper";4 this directive reiterated General MacArthur's authority as SCAP and defined policies for his guidance in the Occupation and the control of Japan. It described Japan as consisting of four main islands : Hokkaido (Yezo), Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and about 1,000 smaller adjacent islands. (Plate No. 24) Later directives extended the area south to 30° north latitude.5

SCAP was granted authority to establish direct military government if necessary;6 he was, however, to exercise his power, as far as compatible with the accomplishment of his mission, through the Emperor of Japan and the Japanese Government.7 This authority determined the administrative character of the Occupation. Direct military government, similar to the type operating in Germany, was not established in Japan. The Japanese Government was permitted to exercise normal powers in matters of domestic administration; certain changes in governmental machinery and personnel were made to insure that requirements of the Occupation were met.

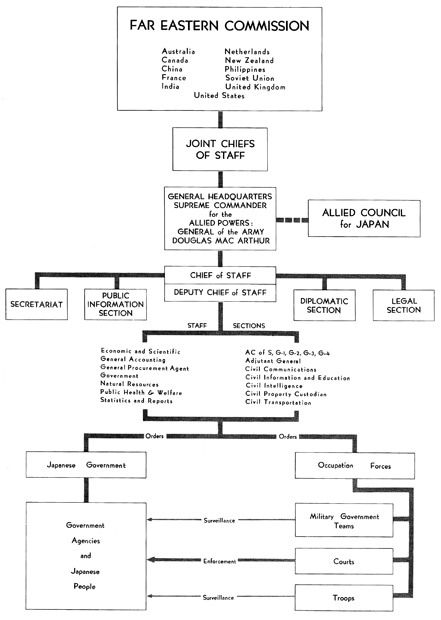

Although in its basic concepts the Occupation of Japan was undertaken on behalf of the principal Allied Powers, in its practical aspects, it was essentially a United States operation. It did assume a more Allied character, however, with the establishment of the Far Eastern Commission in Washington and the Allied Council for Japan in Tokyo. These two organs were agreed upon in a meeting of the Foreign Ministers of the United States, United Kingdom, and U.S.S.R. at Moscow in December 1945, and were subsequently approved by China.8

The Far Eastern Commission was established as a high policy-making body for the Occupation of Japan. It consisted of representatives from eleven nations: China, the United Kingdom, the United States, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, France, the Netherlands, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and the Philippines. The Commission formulated policies, principles, and standards for accomplishing the terms of the surrender; it reviewed, upon the request of any member, directives issued to the Supreme Commander or action taken by him involving policy decisions within the jurisdiction of the Commission; and it considered such other matters as might be assigned to it by agreement among the participating governments. However, the Commission had no authority to make recommendations for territorial adjustments nor to conduct military operations.9

The Allied Council for Japan was initially

[69]

PLATE NO. 24

Area Controlled by SCAP

[70]

an advisory body. It was located in Tokyo and consisted of four members: the Supreme Commander (or his Deputy), who was Chairman and United States Representative; a representative each from the Soviet Union and China; and a member representing jointly the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and India.10 The Council met every two weeks "to consult with and advise" the Supreme Commander on the implementation of the terms of surrender, the occupation and control of Japan, and any supplementary directives; it exercised certain limited authority.

The Supreme Commander carried out the terms of the basic directive and supplementary interim directives of the U. S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Policies adopted by the Far Eastern Commission were transmitted to him through the Joint Chiefs of Staff. SCAP issued the necessary orders and directives to the Japanese Government and to the Occupation forces, and insured that these orders were put into effect.

Despite the fact that he was directly responsible to the U. S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, he consulted and advised the Allied Council for Japan on matters of substance in the execution of policy decisions of the Far Eastern Commission.

In the event that a member of the Council disagreed with the Supreme Commander's proposed action regarding the execution of policy decisions of the Far Eastern Commission, concerning a change in the regime of control, fundamental changes in the Japanese constitutional structure, a change in the Japanese Government as a whole, or related matters, the Supreme Commander did not issue final orders until there was agreement with the Far Eastern Commission.11 (See Plate No. 25 for visual presentation of relationships discussed.)

Organization of General Headquarters,

SCAP

After the appointment of General MacArthur as Supreme Commander,12 a General Headquarters for SCAP was established with origins in the then existing GHQ, AFPAC (U. S. Army Forces in the Pacific); GHQ, AFPAC, and GHQ, SCAP, were physically combined and, for practical reasons, a number of staff sections, agencies and individuals continued to perform dual roles for SCAP and AFPAC. There was, however, a distinct demarcation between the authority and responsibility of SCAP and CINCAFPAC. SCAP's authority was limited to Japan, whereas CINCAFPAC commanded all Army Forces in the Pacific area.

The Supreme Commander exercised authority over all land, sea, and air forces which were then assigned to Japan. These forces included the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF)-the only representative Allied force present-the U.S. naval forces, and U. S. air forces. The Eighth U. S. Army was the actual Army of Occupation13 and was charged with the tactical mission of implementing and enforcing SCAP directives.

The Supreme Commander exercised control

[71]

PLATE NO. 25

The Machinery of the Occupation of Japan from the Far Eastern Commission

through SCAP to the Japanese People, December 1948.

[72]

of the Japanese people through the normal administrative organs of the Japanese Government. The established form of communication was a memorandum for the Japanese Government (known as a SCAPIN), authenticated by the Adjutant General, and dispatched through the Liaison and Coordination Office, an administrative agency in the Prime Minister's Office.14 The Liaison and Coordination Office then transmitted the memorandum to the proper ministry or other agency of the Japanese Government for necessary action. To insure Japanese compliance with the directives of the Supreme Commander, two methods were used transitory inspections by representatives of the staff sections of GHQ, and continuous observation and surveillance by the Occupation forces.15 In order to accomplish these aims, the Eighth Army utilized the military government teams which had been organized, prior to the surrender, for possible use in establishing direct military government in Japan.16

The General Staff Sections, AFPAC, performed certain limited duties for SCAP.17 For example, the G-1 for AFPAC was also the G-1 for SCAP; the General Staff, however, did not coordinate the activities of the SCAP Civil Sections except in matters affecting the Occupation forces from a specific military point of view.18

There were other equally important enforcement and surveillance agencies operating on a national scale from the outset of the Occupation: Counter Intelligence, Censorship, Public Safety, the Military Police and local Provost Marshal.

Functions of General Headquarters,

SCAP

General Headquarters, SCAP, functioned along the lines of a conventional military staff, but since SCAP was charged with the primary mission of steering the Japanese nation and people along the lines of SCAP directives, its staff structure was designed to meet requirements of Japanese civil affairs in all phases of human activity.

Operations instructions, SCAP, were carried out by the Eighth U. S. Army19 and, when practicable, through the CG, FEAF, and COMNAVJAP. The Supreme Commander exercised jurisdiction over the air forces allocated to the Occupation through the CG, FEAF;20 the latter also had operational control over BCOF's air contingent.21

BCOF was integrated in and under the operational control of the Eighth U. S. Army

[73]

and received operational orders in the same manner as United States forces.22 The Commanding General, BCOF, however, had direct access to the Supreme Commander on matters of major policy of his force.23 BCOF was administered and supported logistically by the British Commonwealth and had direct communication with the British Commonwealth Joint Chiefs of Staff in Australia.24

The Supreme Commander exercised command of naval forces allocated to the Occupation through COMNAVJAP. Actually the headquarters of COMNAVFE (Commander, U. S. Naval Forces, Far East) and COMNAVJAP were physically combined. COMNAVJAP controlled the coastal waters of Japan, commanded all naval activities ashore in the Occupation area, and exercised operational control of all naval forces, both U. S. and Allied, assigned to the Occupation of Japan.25 COMNAVJAP also controlled activities of Japanese shipping through SCAJAP (Shipping Control Authority for the Japanese Merchant Marine).26 SCAJAP played an important role in the general repatriation movements.

As naval representative of SCAP,27 COMNAVJAP was responsible for the disposal and scrapping of the Japanese Navy;28 repatriation of Japanese and other foreign nationals;29 mine-sweeping in Japanese waters;30 the supervision of the Japanese Merchant Marine;31 and declaration and disposal of surplus naval property.

The Military Government teams which the Eighth Army used to insure Japanese compliance with SCAP directives were spread throughout Japan to cover the principal centers of population and industry.32 The Army commander, however, was not limited to these teams in his supervision, but used tactical troops in surveillance missions when necessary.33

Progressive steps were taken to enforce SCAP's orders. First, the Japanese Government was held responsible for its actions and for the enforcement of laws, ordinances, and regulations which were promulgated to carry out the instructions of SCAR Secondly, juridical enforcement was effected by the military occupation courts. They had sole jurisdiction with Japanese courts over any act prejudicial to the objectives of the Occupation.34 Ultimate enforcement rested with the Occupation troops.

[74]

The Civil (Non-Military) Staff

Sections, SCAP

Before the Japanese surrender in August 1945, a Military Government Section was established in GHQ, AFPAC, to administer occupied Japan.35 This section with its subordinate units was to take over the Government of Japan in every phase of activity. It assumed the duties of preparing plans for direct military government of Japan.36 Personnel specially trained for military government were assigned to the Military Government Section and to the Sixth and Eighth Armies, where they performed staff functions at army, corps, and division levels and were organized into units for use at the prefectural and local levels.37

On 28 August 1945 Military Government activities of army and corps commanders were limited to a few specified functions and the following policies were set forth:38

(1) SCAP will issue all necessary instructions directly to the Japanese Government.

(2) Every opportunity will be given the Government and people of Japan to carry out such instructions without further compulsion.

(3) The Occupation Forces will act principally as an agency upon which SCAP can call, if necessary, to secure compliance with instructions issued to the Japanese Government and will observe and report on compliance.

A 6 September basic Occupation policy directive ordered that:39

... in view of the present character of Japanese society and the desire of the United States to attain its objectives with a minimum commitment of its forces and resources, the Supreme Commander will exercise authority through Japanese Governmental machinery and agencies, including the Emperor, to the extent that this satisfactorily further United States objectives.

Certain supervisory activities of the Military Government Section were then transferred to the newly established Economic and Scientific and Civil Information and Education Sections of General Headquarters, AFPAC40

On 26 September the Chief of Staff, AFPAC, announced that:41

(1) So long as the system of enforcing the Potsdam Declaration and the surrender terms through the Japanese Government worked satisfactorily, there would be no direct military government in Japan.

(2) A number of special staff sections would be established by General Headquarters, SCAP, to advise the Supreme Commander on non-military matters in relation to the occupation of Japan.

(3) The Military Government Section, General Headquarters, USAFPAC would be discontinued and its remaining personnel transferred to the several new staff sections or to the military government of Korea.

The Supreme Commander established General Headquarters, SCAP, on 2 October 194542 with general and special staff sections, using

[75]

the G-1, G-2, G-3, G-4, and Adjutant General's Sections and the Public Relations Office of U. S. Army Forces, Pacific43 to perform their respective functions for SCAP.44

Ten special staff sections were activated on 2 October: the Economic and Scientific, Civil Information and Education, Natural Resources, Public Health and Welfare, Government, Legal, Civil Communications, Statistics and Reports, and Civil Intelligence Sections, and the Office of the General Procurement Agent.45 Those subsequently established were the Office of Civilian Personnel, International Prosecution Section, General Accounting Section, Civil Property Custodian, Diplomatic Section, and Civil Transportation Section.46

The Civil Intelligence Section was discontinued on 3 May 1946 and its duties assumed by the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2.47 On 29 August it was reactivated48 but continued under operational control of G-2 in his dual capacity as Chief of Theater Counter Intelligence.

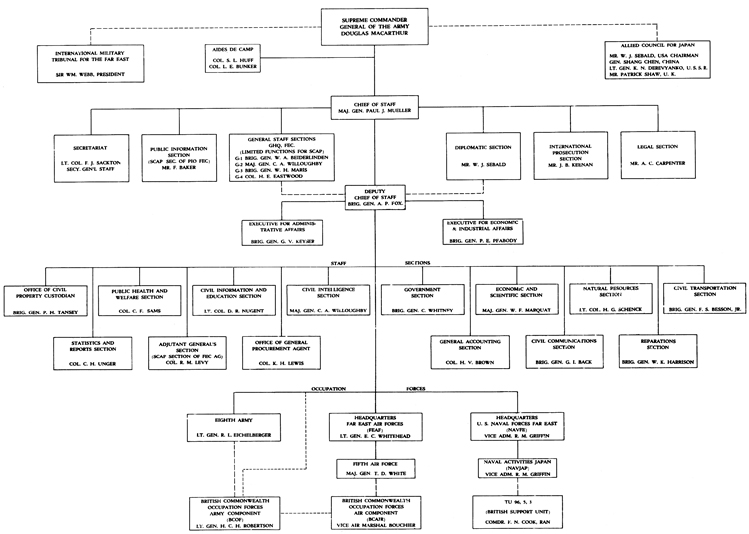

The SCAP Sections (Plate No. 26) corresponded in general to the technical branches of the Japanese civil government with which they were associated.49 They were responsible for making recommendations to the Supreme Commander on policies and actions which would implement the terms of the surrender and the directives received from higher authorities. They carried on continuous research and analysis and maintained close liaison with their counterparts in the Japanese Government.50 They operated directly under a Deputy Chief of Staff who was assisted by an Executive for Administrative Affairs and an Executive for Economic and Industrial Affairs.

These staff sections of SCAP Headquarters were charged with responsibility for initiating action on Occupation matters, and with continuing necessary staff action to follow the assigned tasks through to completion.51 In cases where several staff sections had a major interest in a problem, the initiating section was responsible for accomplishing intra-staff liaison to bring about complete and coordinated action. In effecting this liaison, staff sections were directed to make liberal use of personal contact and other informal methods.52

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) was not a part of the Headquarters, but a related operating agency. It was established by the Supreme Commander on 19 January 1946 for the just and prompt trial and punishment of major war criminals in the Far East. It consisted of judicial representatives of nations who were members of the Far Eastern Commission. The Supreme Commander was charged with reviewing the proceed-

[76]

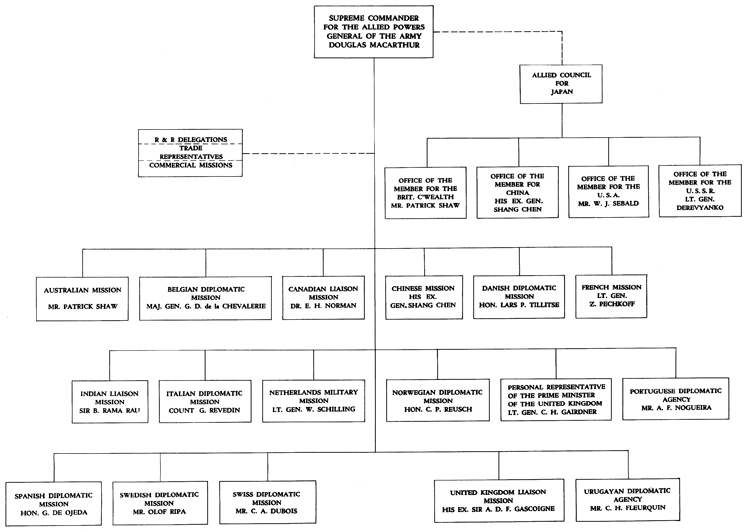

PLATE NO. 26

General Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, 31 December 1947

[77]

ings of the Tribunal on the completion of its work and with the execution of its judgments.53

The International Prosecution Section was established as a special staff section to prepare for trial and prosecute all cases involving crime resulting from planning, preparing, initiating, or waging of a war of aggression or a war in violation of international treaties and agreements, or participation in a common plan or conspiracy for the accomplishment of any of the foregoing.54

The Legal Section was established as a special staff section to advise the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers on : general policies and procedures with respect to war crimes in categories other than the international aspects, which are commonly known as violation of the laws or customs of war, and to supervise the prosecution of war criminals accused of such offenses; general policies and procedures with respect to Occupation courts; and legal matters of a general nature. This section investigated such war crimes as mentioned above, prepared such cases to be tried, established and maintained a central registry of all Japanese war criminals and suspects and made recommendations pertaining to their apprehension and incarceration (this comprised all categories of war criminals). It recommended composition of military courts, commissions or other tribunals for the trial of Japanese war criminals accused of violation of the laws or customs of war, and the rules and procedures for the guidance thereof, and recommended composition of military courts, commissions or other tribunals for the trial of persons accused of violation of the rules and regulations of the Occupation forces, and the rules and procedures for the guidance thereof.55

The Diplomatic Section, an outgrowth of the Office of the United States Political Advisor for Japan, was an integral section of GHQ, SCAP.56 It dealt with international affairs pertaining to Japan. The Section controlled relationships with foreign diplomatic representatives and supervised other U. S. State Department agencies in Japan.57 As chairman and member for the United States on the Allied Council for Japan, the chief of the Diplomatic Section was also deputy for the Supreme Commander.

The Economic and Scientific Section was established as a special staff section which was responsible for developing economic, industrial, financial, and scientific policies to be pursued in Japan in order to implement the Potsdam Declaration.58 Its functions consisted of making recommendations towards maximum production and equitable distribution of essential goods among the civil population and the maximum production of supplies required by the occupying forces. It coordinated the activities of commercial, technical, and industrial missions from the United States and Allied nations which were concerned with the economic, industrial, financial, or scientific rehabilitation of Japan.59 The Economic and Scientific Section also advised the Supreme Commander on Japanese labor policies and programs, including labor relations and labor unions; employment and employment exchanges; wages, salaries, and hours; protective

[78]

labor legislation; and labor procurement for the Occupation forces.60

SCAP's mission in the economic field in Japan was an integral part of the total Occupation objective, namely, to insure that Japan would not again, alone or jointly with other powers, commit aggressive warfare. In an attempt to carry out this mission, three major lines of action were followed in the economic field: the industrial and scientific disarmament of Japan, the democratization and reform of the economic structure, and the restoration of the Japanese general economy on a self-supporting basis. Since Japan could feed herself only by exporting manufactured products, her economy was closely geared to foreign trade. American aid was limited to the most urgent requirements necessary to avoid disease and unrest in the harassed population. American appropriation made possible the importation of food, fertilizer, petroleum products, and medicines. With the exception of cotton, Japan had no funds to import raw materials.

In March 1947 ESS was granted the power to issue licenses to approved foreign concerns desiring to conduct business in Japan. Such licenses incorporated restrictions which were necessary to assure compliance with all existing regulations.61 On 15 August 1947, private foreign trade representatives were permitted to enter Japan.

As a still further potential stimulus to foreign trade, SCAP projected a plan to use Japanese-owned gold and silver as a base for acquiring foreign credits. This was achieved by creating the "Occupied Japan Export-Import Revolving Fund" which was to be used as a credit base for financing importation of raw materials for processing and exporting. This credit base was first utilized on 13 May 1948 when one government and three private banks pledged to finance a 60,000,000 dollar credit. The Economic and Scientific Section was responsible for advising the Supreme Commander on policies and programs relating to the custody, operation, management, and control of this fund.62

The Natural Resources Section. Although Japan claimed that the basic reason for her aggression in the Far East was economic, the chief cause being the desperate need for raw materials, the ironic result was further depletion of her meager resources. To establish favorable economic conditions, which would help prevent the revival of militarism, it was necessary to increase Japan's resources to satisfy her needs and to democratize her institutions.

The Natural Resources Section was established as a special staff section to advise SCAP on agricultural, forestry, fishery, and mining (including geology and hydrology) policies and activities in Japan.63 It arranged for and co-ordinated surveys and reports; located source data in Japan relating to agriculture, forestry, fishing and mining in countries formerly occupied by Japan; and recommended measures to insure the development, exploitation, production, processing, and distribution of basic industry products required for rehabilitation of the national economy.

The Civil Intelligence Section maintained a national system of intelligence and information coverage through its law enforcement and surveillance agencies. This section was the operating agency for counterintelligence and general security functions within the command and was primarily responsible for the dissolu-

[79]

tion and surveillance of ultra-nationalistic and militaristic organizations. It was charged with public safety matters in Japan, including police, prison, maritime safety, and fire control systems, and also maintained censorship of Japanese information media, mail, and telecommunications.64

The Government Section was responsible for policies pertaining to the internal structure of civil government in Japan.65 It investigated and reported to the Supreme Commander any modifications and reforms of civil government in Japan. It made recommendations regarding the demilitarization and decentralization of the Japanese Government as well as elimination of feudal and totalitarian practices. It investigated, reported, and made recommendations regarding laws, policies, practices, procedures, and other factors in the personnel administration of the Japanese Government, in order to develop democratic precepts, integrity, and efficiency in its administration.

The Civil Communications Section's functions were to rehabilitate and operate civil signal and postal communications in Japan.66 It arranged for and coordinated surveys and reports on existing teleradio and postal communications systems and on laboratories and educational institutions which were adapted to the study of problems relating to signal communications facilities and conditions.

The Public Health and Welfare Section was required to initiate policies relating to public health and welfare problems.67

The primary consideration in public health and welfare activities was to achieve a level of health and welfare among the civil population which would prevent widespread disease and unrest likely to interfere with the Occupation. The major problem in attempting to achieve this goal was the lack of trained and qualified Japanese personnel to conduct the various programs at national, prefectural, and local levels. Also, there were not enough personnel among military government teams to supervise SCAP-directed national programs. A complete public health organization, from the Ministry of Welfare down to and including the health center level, was established throughout Japan. This called for many educational and training programs to instruct Japanese officials in modern public health and welfare practices. The improvement of public health and the development of welfare activities was an integral part of the program designed to help develop civic responsibilities.

The Civil Information and Education Section had the job of formulating policies for public education, religion, and other sociological problems of Japan.68 It concentrated on educational and sociological reforms, with particular reference to the democratization of the national school system. It made recommendations to insure the elimination of doctrines of militarism and ultra-nationalism, including juvenile military training, from all elements of the Japanese educational system.69 It also insured the protection, preservation, and salvage of works of art and antiquity, cultural treasures, religious articles, libraries, museums,

[80]

archival repositories, religious buildings, and historical monuments.

The Civil Transportation Section's duties consisted of making plans for the use and rehabilitation of water and land civil transportation facilities of Japan, except for operating responsibilities assigned to Commander, Naval Activities, Japan.70 The Civil Transportation Section, in conjunction with the Economic and Scientific Section, established requirements and priorities in raw materials and industrial capacity necessary to provide the facilities and equipment for the transportation system in order to serve the essential needs of the internal economy of Japan.

The Statistics and Reports Section was responsible for the collection, tabulation, and presentation of statistical and other special and routine reports which pertained to the non-military aspects of the Occupation of Japan.71

The General Procurement Agent coordinated, controlled and issued regulations governing the procurement of supplies, equipment, materials, services, real property, and facilities in Japan in order to prevent competition in procurement. It provided for the equitable allocation of supplies, equipment, materials, real property and facilities, and services; standardized procedures for procurement; and effected equitable allocation of Japanese resources. The General Procurement Agent was also responsible for liaison with the Central Liaison Committee of the Japanese Government.72

The General Accounting Section was responsible for general policies and procedures pertaining to financial accounting matters and maintained records covering the financial aspects of the Occupation.73

The Office of the Civil Property Custodian advised on general policies and controlled and disposed of enemy and Allied properties and assets under its jurisdiction.74 This office recommended and established procedures, and executed approved programs for the blocking and impounding of property which was acquired by Japan under duress, wrongful acts of confiscation, dispossession or spoilation. Lastly, it was responsible for the maintenance of complete records and accounts of all confiscated property and its disposal.

The Reparations Section planned the program for processing Japanese industrial assets considered available for claim and removal as reparations.75

The Reparations Technical Advisory Committee was established as a consultative committee to assist the Supreme Commander in the development of technical and administrative procedures to assure an orderly removal of reparations goods from Japan and in settling problems between countries arising over claims.76 The Chairman of the Committee was the Chief of the Reparations Section. The other members of the Committee were chiefs of the Reparations and Restitutions Delegations which represented the Far Eastern Commission.

The Restitution Advisory Committee was established to assist the Supreme Commander in matters dealing with the disposition of property found in Japan and identified as having been located in an Allied country and removed to Japan by fraud or coercion by the Japanese or their agents.77 The Restitution Advisory Committee consisted of a chairman and one member from each of the Reparations and Restitution Delegations representing nations in

[81]

the Far Eastern Commission who desired to participate. The Civil Property Custodian was Chairman of the Committee.

In addition to the administrative and advisory staffs authorized for the members of the Allied Council of Japan, a number of foreign diplomatic representatives, pre-war embassies, legations and agencies were accredited to SCAP rather than to the Japanese Government. (Plate No. 27) These diplomatic agencies served as channels of communication on operational and administrative matters between their governments and SCAR Certain functional representatives, distinct from these missions, worked directly with SCAP in handling matters which pertained to restitution and reparations, as well as to foreign trade, on a government to government basis.78

Establishment and Missions of FEC Far East Command

On 1 January 1947 a GHQ, FEC, order established the Far East Command, with General MacArthur as Commander in Chief.79 This command was established as an interim measure for the immediate post-war period, with particular consideration to the tactical requirements for protracted occupation of former enemy areas. It was, in fact, an adaptation of the then existing AFPAC organization, with no change in the GHQ staff. It was simply the old staff continuing under a new name, with many of its officers remaining in the same relative positions.

The Far East Command included the United States forces in Japan, Korea, the Ryukyus, the Philippines, the Marianas and the Bonins.80 General MacArthur exercised unified command over all forces allocated to him by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Allied Powers ; however, it was at this time that the Army Forces in the Middle Pacific (AFMIDPAC) passed from his control.

The Commander in Chief, Far East Command, (CINCFE) was made responsible for United States occupation functions in Japan and in Southern Korea, and United States military duties in the Philippines. He was also responsible for security of the Far East Command, including the protection of sea and air communications, United States policy within the limit of his command, and support of the Commander in Chief, Pacific, in his mission. Lastly, he was charged with making plans and preparations in case of a general emergency. He was to provide for the safety of United States forces in Korea and China ; oppose enemy advances; secure Japan, the Ryukyus, the Marianas, and the Bonins; and discharge United States military responsibilities in the Philippines.81

In the event of an emergency declared by General MacArthur, United States forces in China were to come under his control.82 He was also assigned operational control of the facilities and local forces in the Marianas and

[82]

PLATE NO. 27

Foreign Diplomatic Missions and Agencies in Japan, September 1948

[83]

Bonin Islands;83 this change was significant because the control did not include responsibility for the military and civil government of these islands, nor any responsibility for naval administration and naval logistics.84 The over-all plan, however, did make General MacArthur responsible for their security; local forces and their facilities were assigned to his operational control to assist him in discharging his mission.85

Command Structure of General

Headquarters, FEC

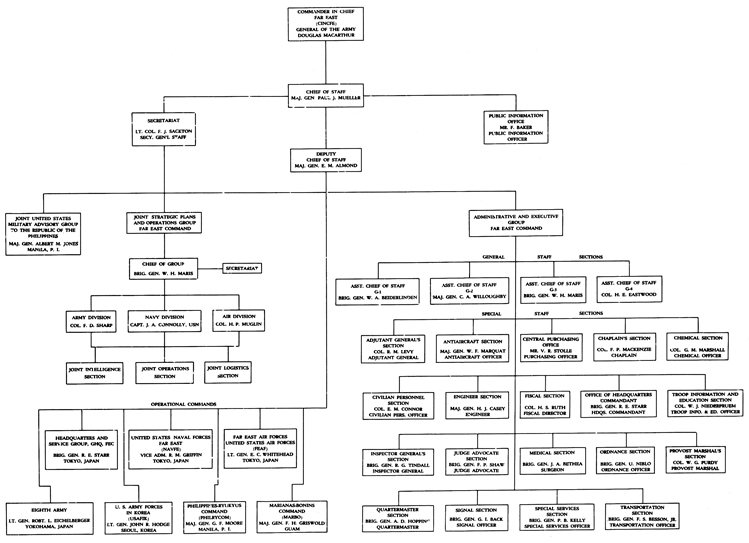

The organization through which CINCFE administered and controlled the far-flung tactical establishment of FEC was a General Headquarters. It consisted of a conventional high-level military staff, with the addition of a Joint Strategic Plans and Operations Group. There was also an increase in the number of special staff sections. (Plate No. 28)

The Joint Strategic Plans and Operations Group became an important staff element in the exercise of unified command. It consisted basically of three small, co-equal Ground, Navy and Air Staff Groups which furnished planning teams for joint intelligence, joint operations and joint logistic planning. The Group was small, and its functions were limited to the preparation of joint plans for possible major emergencies.

The bulk of General Headquarters was located in the Administrative and Executive Group, which consisted of a conventional high-level General Staff and a Special Staff. This Group handled the major part of CINCFE's military operational functions, including those administrative aspects of joint command pertaining to the peacetime missions of the three services.

It should be mentioned again that the nature and duties of the General and Special Staff Sections did not change with the order creating the Far East Command. The change was merely in nomenclature-for example, G-3, GHQ, AFPAC became G-3, GHQ, FEC.

The primary mission of the Far East Command was to support the Occupation of Japan and Southern Korea.86 A major portion of the Far East Command, including the British Commonwealth Occupation Force, carried out Occupation missions in Japan under the direct control of SCAP.87 The command structure of the Far East Command and the allocation and distribution of forces was dictated by the

[84]

PLATE NO. 28

General Headquarters, Far East Command, December 1947

[85]

missions and the military geography of the area. (Plate No. 29)

By far the largest number of United States Ground Forces allocated to CINCFE were assigned to the Eighth Army, the major command charged with the tactical mission of occupying Japan. United States forces under the Eighth Army were divided into two corps-the IX Corps and the I Corps, each consisting of two divisions. The British Commonwealth Occupation Force came under General MacArthur's operational control in his capacity as Supreme Commander and was assigned to Eighth Army. The XXIV Corps, consisting of two United States divisions, occupied Korea and was designated as U. S. Army Forces in Korea (USAFIK).

Generally speaking, the Far East Command was divided into an "Occupation Area" and a "Support Area," with major ground combat elements located in the Occupation Area. The remaining ground troops, primarily service troops and Philippine Scouts, were distributed among the major ground headquarters in the Support Area, and the Ryukyus, Philippines and Marianas-Bonins Commands. All of these, like Eighth Army and XXIV Corps, were army components. There was no over-all headquarters for the ground elements within the Far East Command, and the four separate ground commands reported directly to CINCFE.

Because of their greater mobility, command of naval and air forces within the theater followed a somewhat different pattern, making it mandatory that control for each of these services be centralized in a single commander. The Commander, Naval Forces, Far East, (COMNAVFE) controlled all naval forces assigned to CINCFE and exercised his authority through appropriate subordinate naval headquarters.88 The Commanding General, Far East Air Forces, (CG, FEAF) was responsible for all air forces assigned to the Far East Command,89 including operational control of the British air contingent in Japan. He exercised his power through three Air Force headquarters and Headquarters, 1st Air Division. Within the over-all air and naval commands, the subordinate structure conformed to the geographical areas where the naval and air bases were located.

CINCFE controlled all ground forces and activities in the Ryukyus, including Military Government, through the Commanding General, Ryukyus Command. The over-all objective of the Military Government administration in the Ryukyu Islands was to maintain exclusive United States control in this area until such time as the international status and the future administration of these islands was determined.90

The Philippine Command had only a small force, maintained primarily as a supervisory echelon for the direction of the activities of the Philippine Scouts.91 The Scouts, although still retaining a number of combat unit designations, performed guard duty over surplus property

[86]

PLATE NO. 29

Territorial Subdivisions, Far East Command, December 1947

[87]

and provided the bulk of the troop labor.92

CINCFE also had jurisdiction over all United States Ground Forces in the Marianas-Bonins Area, known as the Marianas- Bonins Command (MARBO).93 MARBO consisted almost entirely of service troops, including some scouts.

Subordinate Navy echelons were located in the same areas as the ground commands. In Japan, COMNAVFE had a dual assignment as Commander, Naval Activities, Japan (COMNAVJAP). In the Philippines, COMNAVFE commanded the local naval forces through the Commander, Naval Forces, Philippines (COMNAVPHIL).94 The Commander of the Marianas Islands (COMMARIANAS) was under COMNAVFE for the operational control of local naval forces and under CINCPAC for those naval functions which did not come under CINCFE.95 These functions included responsibility for the civil government of Guam, the United States trusteeship over the mandated islands, and the Naval Military Government in the Volcano Islands. Since the last two groups had been previous possessions of Japan, they were not included in the trusteeship agreement. COMMARIANAS also commanded naval forces in the Caroline and Marshall Islands and reported in this capacity directly to CINCPAC. Military and naval government in the Marianas-Bonins area was specifically excluded from CINCFE's mission,96 and COMMARIANAS came directly under CINCPAC and the U.S. Pacific Fleet for these functions. United States trusteeship over the former Japanese mandated islands was administered through naval channels and was not a function of CINCFE.

The subordinate echelons of the Far East Air Forces also corresponded to the principal land areas. Since the primary mission of the ground forces in the Marianas-Bonins Area was the support of the air forces, the Commanding General, 10th Air Force, was also placed in command of the ground forces. In his first capacity he reported to CG, FEAF, and in his second role, he reported directly to CINCFE.

Under the established structure, the unified command of air, ground, and naval elements was exercised only by CINCFE. However, in an emergency, local commanders were to assume jurisdiction over all Far East forces within their areas and execute previously prepared plans. This arrangement insured unified action in an emergency and, at the same time, left the command structure flexible enough to permit independent employment of air and naval forces.

[88]

Go to

Last updated 11 December 2006 |