CHAPTER IV

RELIEF OF PRISONERS OF WAR AND INTERNEES

Allied prisoners of war in Japanese custody, including merchant seamen, are (to be) repatriated at the earliest possible date consistent with military operations. The urgency of this mission is second only to military operations and to the maintenance of the forces of occupation.1

Thus read the operational instructions implementing Operation "Blacklist," the basic plan for the occupation of Japan and Korea on the surrender of the Imperial Japanese Government. Within a few hours after the first reconnaissance party of Americans arrived at Atsugi airfield to initiate the pre-surrender requirements, the first Allied prisoners of war became free men. Three weeks later virtually all those held as prisoners on the Japanese mainland had been evacuated and were on the way back to their homes. The speed of liberation from all prison camps in Honshu, Hokkaido, and Shikoku within the first two weeks of September put the Eighth Army weeks ahead of the most optimistic estimates made for this enterprise.2

Prior to the cessation of hostilities there was considerable concern in General MacArthur's Headquarters about the fate of the prisoners of war and civilian internees. The care and evacuation of these persons were important objectives in the specific plans which senior staffs were directed to develop and maintain in an advanced state of readiness, as a matter of urgent priority."3

One of the major missions outlined in "Blacklist" was to locate United Nations prisoners of war and internees, to provide them with adequate food, shelter, clothing and medical care, and to register and evacuate them to rear areas.4

As defined by "Blacklist," the term "United Nations prisoners of war" included all persons held in Japanese custody, who were or had been members of, or accompanied or served with, the armed forces of any of the United Nations; captured members of the armed forces of countries occupied by Japan, as well as those who had served with the merchant marine of any of the United Nations, were also included. All of these categories, under terms of the Geneva Convention, should have been treated as prisoners of war even though not recognized as such by Japan; at the same time, "Blacklist" designated a civilian internee as a person "without a military status, detained by the enemy, who is not a national of the Japanese Empire as constituted on 10 July 1937."5

The general term did not include personnel

[89]

who, although formerly held in Japanese custody as prisoners of war, had accepted release from the status in exchange for employment by Japan. Persons in this category, after definite identification, were to be dealt with as displaced persons.

The "facts and assumptions" of "Blacklist," though a pre-surrender document, proved generally correct:

Best estimates indicate that there are approximately 36,000 (Allied) personnel of various categories located in approximately 140 camps. In most instances this personnel will be in extremely poor physical condition requiring increased diet, comforts and medical care. Poor housing and sanitary conditions will require immediate large scale transfers to best available facilities to be peremptorily commandeered. Complete re-clothing will be imperative. Records in general will be incomplete for both survivors and deceased.6

SCAP Directives Regarding

Prisoners of War

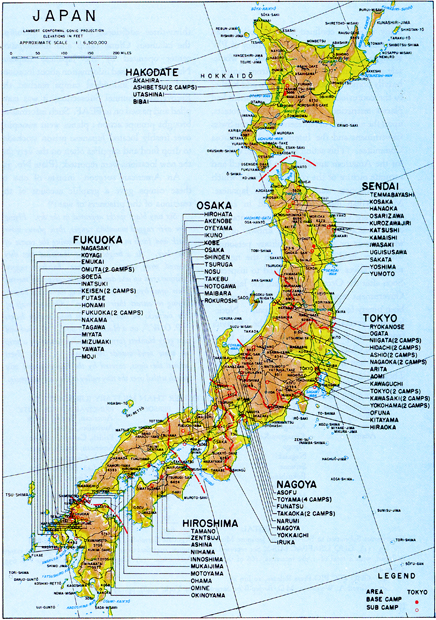

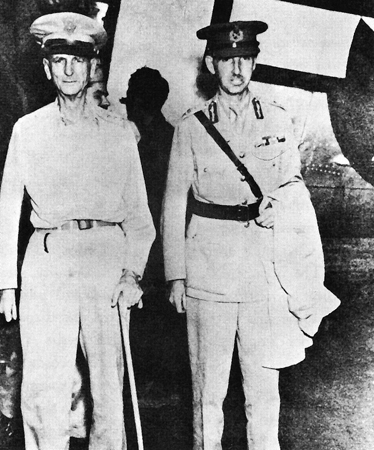

Document I of the "Requirements of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers Presented to the Japanese Representatives at Manila, P. I., on 19 August 1945", called for the Japanese surrender delegation to be prepared to furnish all available information pertaining to "prisoner of war and civilian internment camps and places of detention, wherever located, within Japan and Japanese controlled areas." The location and status of Generals Jonathan M. Wainwright and Arthur E. Percival, top-ranking United States and British prisoners of war, were specifically required.

The Japanese emissaries at Manila presented an agreement to return prisoners of war and internees immediately. They asked to be notified as soon as possible as to where and when the Allied Nations would have the necessary ships for the prisoners' repatriation, and indicated that the following ports had been selected as embarkation points: Hakodate, Niigata, Aomori, Fushiki, Tsuruga, Sendai, Yokohama, Nagoya, Kobe, Shimonoseki, Nagasaki, and Hakata. They further stated that a committee comprised of members of the Prisoner of War Information Bureau, Army and Navy Ministries, and the Foreign Office had been formed. The committee was to make preparations to return Allied prisoners, with assistance from the Swiss and Swedish Legations and the International Committee of the Red Cross in Japan.7

Elaborating on the prior demand, the earliest SCAP directives to the Japanese Government prescribed a speedy release of the prisoners.8 On 2 September, SCAP General Order Number 1 ordered:

(1) The safety and well-being of all United Nations Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees will be scrupulously preserved, to include the administrative and supply services essential to provide adequate food, shelter, clothing and medical care until such responsibility is undertaken by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

(2) Each camp or other place of detention of United Nations Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees together with its equipment, stores, records, arms, and ammunition, will be delivered immediately to the command of the senior officer or designated representative of the Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees.

(3) As directed by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees will be transported to places of safety where

[90]

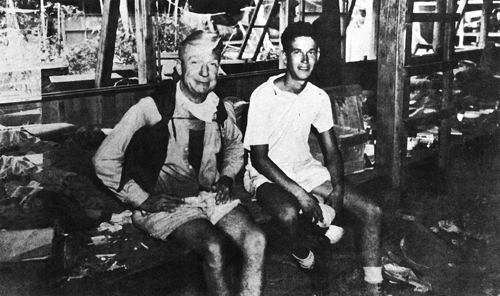

Gens. Jonathan M. Wainwright and Arthur E. Percival

after release from PW Camps in Manchuria.

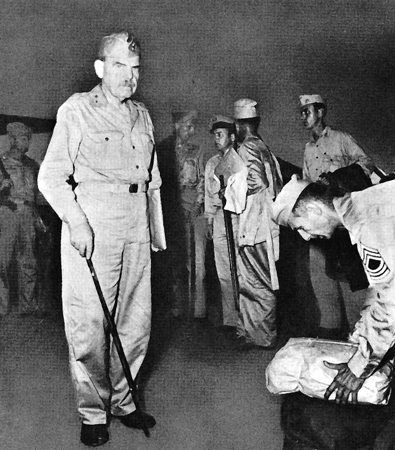

Maj. Gen. E. P. King at Nichols Field,

Manila, on his way to the United States.

PLATE NO. 30

Senior Allied Commanders Released from Prisoner of War Camps.

[91]

they can be accepted by Allied authorities.

(4) The Japanese Imperial General Headquarters will furnish to the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, without delay after receipt of this order, complete lists of all United Nations Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees, including their locations.

A day later, Directive Number 2 instructed the Japanese Imperial Government to dispatch instructions for all prisoners of war and civilian internees without delay. The prisoners were to be assembled at the earliest opportunity and the following statement was to be read to them in English and in such other languages as might be required:

The formal surrender of Japan to the Allied Powers was signed on 2 September 1945. General of the Army Douglas MacArthur has been named Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. United Nations Forces are proceeding as rapidly as possible with the occupation of the Japanese Home Islands and Korea. The relief and recovery of Allied Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees will be accomplished with all possible speed.

Pending the arrival of Allied representatives the command of this camp and its equipment, stores, records, arms and ammunition are to be turned over to the Senior Prisoner of War or a designated Civilian Internee, who will thenceforth give instructions to the Camp Commander for maintenance of supply and administrative services and for the amelioration of local conditions. The Camp Commander will be responsible to the Senior Prisoner of War or designated Civilian Internee for maintaining his command intact.

Allied representatives will be sent to this Camp as soon as possible to arrange for your removal and eventual return to your homes.

This directive also authorized the requisitioning of government or military stocks

to insure that the prisoners and internees would receive rations equivalent to the highest scale locally available to Japanese armed forces or civilian personnel. All of the prisoners were to be furnished the best medical care possible, together with all necessary medical supplies, and adequate shelter, clothing, and bathing facilities.

Complete lists of all prisoners of war and civilian internees (showing name, rank or position, nationality, next of kin, home address, age, sex, and physical condition) were to be prepared and dispatched to the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. Extracts from available records on deceased or transferred prisoners of war and civilian internees, showing substantially the same data (including data of death and burial site, or transfer and destination), were also to be furnished.

Every military unit arriving in Japan in the days just before and after the formal surrender ceremony on 2 September 1945 played its particular role in the recovery of the prisoners of war and civilian internees.

GHQ, AFPAC, had been given the responsibility to operate and train the necessary liaison, recovery, and final processing teams which would be required to speedily liberate the prisoners.9 The Recovered Personnel Detachment had organized and trained teams to accompany field forces in the anticipated invasion of Japan.10 This project was a joint mission of the Adjutant General and the Commanding General, Special Troops, GHQ. Meanwhile, a liaison team of three officers and three enlisted men (one each from the United States, British, and Netherlands Forces) had been

[92]

trained for duty with each of the two armies and six corps which were scheduled to make the initial entry into Japan.11

The recovery teams (approximately seventy) were set up on the basis of one for each 500 prisoners of war and civilian internees. Each team was composed of two officers-one United States and one British. Twelve additional recovery teams were held in reserve to be attached when needed.12 The final processing teams were to be assigned to the four recovered personnel disposition centers or collecting points proposed for Japan and Korea. Every team was composed of nine officers and twenty enlisted men, and included one officer and one enlisted man from Great Britain, Australia, Canada, and the Netherlands.

The job of locating the prisoners was delegated by GHQ to the commanding generals of the Sixth and Eighth Armies and the XXIV Corps, within their respective areas. Each was charged with the following duties:13

(1) Locate, care for and safeguard all Allied recovered personnel.

(2) Provide billets, food, clothing, comforts and medical care.

(3) Accomplish initial processing of subject personnel....14

(4) Establish recoveree disposition centers near ports of embarkation or landing fields as may be required.

(5) Evacuate recovered personnel to recoveree disposition centers established by Commanding General, AFWESPAC, in the Philippines.

(6) Collect, preserve and forward all records that may be captured pertaining to recovered personnel transport to expedite evacuation.

(7) Exact from the Japanese Government and military command maximum resources and facilities available to assist in the accomplishment ... (of the above).

(8) Assume operation of Allied prisoner of war and internment camps located within their respective areas.

(9) Utilize first available air, motor, or water transport to expedite evacuation.

Duties of the Commanding General, AFWESPAC, were outlined in the same document, as follows:

(1) Provides supplies and equipment required by recovery and processing teams.

(2) Provides Commanding Generals, Sixth and Eighth Armies and XXIV Corps with ample clothing and equipment for prisoners of war and internees including women and children; subsistence of proper type and quantity; medical supplies and facilities to insure adequate medical care of the recoverees.

(3) Establishes and operates a final processing center in the Manila area, consisting of one replacement depot augmented by one British and one Australian processing unit comparable to a Replacement Battalion.

(4) Provides messing detachments, supplies and equipment and administrative facilities at final disposition center.

(5) Receives, billets, and provides rations, clothing and medical care for recovered personnel in recoveree disposition centers established in the Philippines.

(6) Furnishes air, motor or water transportation as may be needed in the movement of recoverees within his area of responsibility.

(7) Processes and evacuates from the Philippines prisoners of war and civilian internees after clearance by this [AFPAC] headquarters and as arranged with

[93]

the governmental authorities concerned.

The planned process of evacuation for Americans, British, Canadians, and Australians was from the camps to recovered personnel disposition centers, to the final processing center, and thence to their destinations. Nationals of the other United Nations were to be held in the final disposition centers until provision could be made by their respective governments for their return home.

Highest priority on transportation was directed, with movement by air to be used to the maximum. Priority was given for the evacuation and repatriation of the sick and wounded, but there was no discrimination because of rank, service, or nationality.

In early August numerous messages regarding the relief and release of internees and prisoners of war were transmitted between Tokyo and Washington via Bern.15 The Recovered Personnel Sub-section was then transferred from Manila to Okinawa in preparation for moving to Japan.16

Meanwhile, the reported conditions of starvation rations, disease, and maltreatment of the men and women in Japanese camps17 spurred military authorities to arrange for immediate relief measures to ease the last days of incarceration.18 It was estimated that thirty days would be required for complete evacuation of Japan, and that many lives could be saved by supplying food, clothing, and medical supplies during the interim.19 Air transport was chosen as the most feasible method of providing the necessary supplies. The original plan called for Far East Air Forces planes, based on Okinawa and in the Philippines, to share the air supply task with Marianas-based B-29's. Just as the program was about to be initiated, the entire project was assigned to the Twentieth Air Force and prisoner of war supply missions were executed from 27 August to 20 September 1945.20

The spearhead of the Tokyo shuttle arrived at Kadena Airfield (Okinawa) in mid-August. They were planes of the Air Transport Command which were to carry the 11th Airborne Division north to Tokyo for the Occupation and bring back the former American prisoners to Okinawa on their way to the States. The Air Transport Command crews, which came from all over the world for this epoch-making operation, shuttled their planes between Tokyo and Okinawa. They were called in from "Snowball": the Presque Isle, Maine-to-Paris

[94]

run; from "Crescent": the Wilmington, Delaware-to-India run; and from North Africa via India and the Philippines.

Because of the nature of the project, it was decided that only general planning would be done at Twentieth Air Force Headquarters. Specific planning on routes, loading, and dates of missions was to be done by the wings engaged in the operation.21 An important factor in planning the operation was the availability of food, medical supplies, and cargo parachutes. It was obvious that if the Twentieth Air Force were to carry out the supply drops quickly, all supplies must be packaged and made available in the Marianas. The food and medical supply requirements for the program were set up on the basis of thirty days' supply for 69,000 persons. (This figure included the Japanese Home Islands, Korea and China. Arrangements were made through the Western Pacific Base Command for all supplies to be made available at Saipan. This was made possible by borrowing on stores and provisions which had been accumulated for the planned invasion of Japan. Since 63,000 cargo parachutes were required for the project and only 11,000 were available in the Marianas, it was necessary to obtain additional ones from the Philippines.

After determining where and in what quantities the necessary supplies could be delivered, loading and dropping tests were conducted by the Operational Engineering Section in order to make detailed plans. Throughout the course of these tests, it was found that a 10,000 pound load consisting of forty individual drop units was the capacity of a B-29. The best altitude during the initial dropping was determined to be between 500 and 1,000 feet; while the most practical speed for the drops was established at approximately 165 miles per hour.

After the first three days of operation, however, it was decided that the established altitude was too low, and crews were briefed to drop bundles above 1,000 feet. This height allowed for better functioning of parachutes, and avoided causing injuries among prisoners and destruction of supply bundles.22 To facilitate identification, all aircraft engaged in these operations were marked "PW Supplies" in letters three feet high under each wing.

Plans were made to drop supplies in increments of three, seven, and ten-day units. The three-day supplies were to include juices, soups, clothing and medical supplies. The seven-day packages would contain additional medical supplies and food of a more substantial nature. The ten-day supplies were to consist of almost all food, with some medical supplies. A fourth increment of additional supplies would simply repeat the three-day unit bundles. Instruction leaflets for allocation and use of supplies were included, and each aircraft was to take

[95]

photos of the operation whenever conditions permitted.

Normally every plane was to carry supplies sufficient for 200 persons for the particular three, seven, or ten-day period. But for camps of 1000 or more population, aircraft were slated for special loads which would provide for greater efficiency in packaging.23

On 18 August 1945 medical supplies for 31,000 people had been assembled, packed, and stored on Guam while quartermaster stores for 50,000 people were assembled, packed, and stored on Saipan. All these supplies were prepared for air-dropping to PW's and internees held by the Japanese.24

Location and Supply of Prisoner of

War Camps

The most perplexing problem in planning these operations was determining the location and population of the camps to be provided. On 16 August 1945 the Commanding General, USASTAF, radioed Commander in Chief, AFPAC, that an official current gist of PW camps and civilian internee centers from Japanese Government sources was urgently needed for the efficient execution of the assigned air drop mission. The camp designation, the number of PW's present, general location, and geographic coordinates were requested. Evacuated camp sites were to be named and located, since the currently available information on this subject was considered too unreliable for the successful execution of airdrops. Because population figures for many of the camps could be only estimates, it was inevitable that there would be cases of over-supply and under-supply. A study prepared by the MIS-X Section of GHQ on 14 August indicated locations, conditions, and strengths of Japanese prisoner of war camps.25 The only positive intelligence on these camps was intermittently furnished by the International Committee of the Red Cross; however, since that agency was allowed to visit relatively few camps in Japan, conditions listed in its reports could not be considered representative. All other camp intelligence came from a variety of sources; much of it was obtained from interrogations of Japanese prisoners and had to be assessed accordingly.26

According to the principles established by the Geneva Convention, the International Committee of the Red Cross was to be notified of the location of all PW camps. Since the Japanese did not consider themselves bound to these principles, it was only after the surrender that this organization was able to obtain access to Japanese prison camp records. In cooperation with Allied authorities, Dr. Marcel Junod, who had been active in International Red Cross activities throughout the war, established a plan for rapid evacuation of prisoners of war and civilian internees. Conditions in Japan, camp strengths as of the latest reports, and plans for evacuation were outlined in a

[96]

radio message via Washington.27

On 29 August, in compliance with SCAP's request for further information, the Japanese radioed that they were trying their best to collect the required data concerning the Allied prisoners of war. They complained, however, that it was practically impossible in so short a time to complete the comprehensive investigation demanded since communications with various places either had been severed or were extremely difficult.28

The first official Japanese compilation of prisoner of war camps, known as the "Yellow List" and containing the names of seventy-three camps, was made available to the Twentieth Air Force on 27 August 1945. After coordinating the location of these camps with those listed in "Blacklist", aircraft of the 314th Bombardment Wing were dispatched to verify the location of camps on the Japanese home islands of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu.29 This reconnaissance established the existence and location of several additional encampments.

When the ground forces began occupation of all strategic areas in Japan, the necessity for air surveillance lessened, and the Far East Air Forces turned their efforts toward deploying air units to Japan for occupation duties and the continued dropping of supplies.30 During the period from 27 August to 20 September, aircraft of the 58th, 73rd, 313th, 314th, and 315th Bombardment Wings flew goo effective

[97]

Sendai PW Camp No. 3 Relief Mission flown by 20th Air Force, 12 September 1945.

Japanese unloading supplies dropped by air at Omori PW Camp near Tokyo, 30 August 1945.

PLATE NO. 31

Prisoner of War Relief Missions

[98]

sorties and dropped 4,470 tons of supplies. Successful drops were made to 158 camps.31

The Navy was notified of these relief operation plans and furnished air-sea rescue facilities, consisting of surface vessels on permanent stations along the routes flown.32

In the outer bay just beyond Yokosuka, elements of the Third U. S. Fleet, under command of Admiral William F. Halsey, had awaited the signal which would allow them to enact the Navy's role in the Occupation mission.33 On 21 August Admiral Halsey had radioed Commander in Chief, Pacific Advance, that beginning on the day of initial landings his command was prepared to provide for and screen a considerable number of Allied prisoners of war and internees. In Tokyo Bay area the Third Fleet had immediately available three hospital ships, thirty doctors, ninety corpsmen, and clothing and food for 3,000 men. By the first of September the Navy expected to have additional small ships, twenty doctors, sixty corpsmen, and food and clothing for 4,000 men.34

The Swiss representative of the International Committee of the Red Cross, with Task Force 31, anchored off Yokosuka, meanwhile reported that many of the PW's were sick (150 were seriously ill in Shinagawa camp hospital) and

[99]

that all camps were in desperate need of food. The Red Cross Committee also furnished information on 200 aviation personnel, in extremely bad condition at Omori camp on the waterfront. The urgency of the situation was confirmed by extensive photographic coverage of PW camps, which showed prisoners signaling to planes for food and medical supplies.35 From the Japanese it was learned that there were supposedly 6,125 Allied PW's in the Tokyo area, of which 417 were bedridden. This distressing situation was further confirmed by two British marines who were rescued by a patrol boat near Sagami Bay anchorage. They had escaped from Kawasaki prison camp, a one-story wooden barracks where there was a critical lack of food, medicine, and clothing. The hopeless predicament of prisoners in Tokyo waterfront camps indicated that their release was one of prime urgency. Medical care was badly needed and had the highest priority. Obviously, there was no reason to assume that the Tokyo area was an exception but that conditions in inland camps were equally bad, a strong reason to handle the problem on an over-all basis rather than piece-meal evacuations on a possibly preferential basis; as a matter of fact, the inland camps required the handling of 30/40,000 internees.

In view of these reported conditions, on 29 August, Admiral Halsey was authorized by Admiral Nimitz to take prompt action regarding the PW's.36 Within a short period the evacuation of waterfront camps was underway. The first prisoners to be evacuated were from Omori, Shinagawa, and Ofuna camps.37 Commander Task Group 30.6 radioed to Commander Third Fleet:38

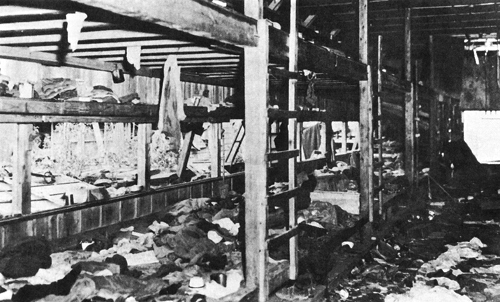

There has never been a blacker hellhole than the POW hospital we are now evacuating one-half mile north of mooring. Approximately 500 have now (30 August) been processed to Benevolence including fracture, open wounds, concussions, burns and in general the worst malnutrition imaginable. Bestial beatings were common especially at Ofuna, inquisitorial den of brutism. The cheers of POW as our boat hove into sight brought tears to our eyes. Operations are proceeding according to plan. The bath, medical care, chow, interview, and clean bed routine is a merciful machine of efficiency.... Preliminary list of POW will be sent Commander 3rd Fleet in morning.

A touching scene greeted rescuers at the camp near Yokosuka Naval Base. There, more than 1,000 emaciated and starving Allied war prisoners were taken aboard the USS Ancon.

[100]

Close-up of Barracks, Omori Prisoner of War Camp.

Leon S. Johnston of Atlanta, Georgia, and Harry R. Sanders of

Terre Haute, Indiana, interned for over three years at Omori Camp.

PLATE NO. 32

Barracks, Omori Prisoner of War Camp, Tokyo, 30 August 1945

[101]

Among them were the gallant survivors of Wake and Bataan who had withstood long months of solitary confinement and threats of death. At least 80 percent of them were suffering from malnutrition;39 all of the prisoners at Omori and Shinagawa camps, except for the few who were of recent capture, were suffering from the same deficiency, a majority of them seriously. Many were medical and surgical cases. The conditions in these two camps had been abominable and the treatment extremely brutal. The third camp, Ofuna, had been the Gestapo center of Japan.

Recovered Personnel Section in Action

As stated previously, the Occupation ground forces had also made careful plans for their part in the evacuation program. The Recovered Personnel Sub-section of G-1, Eighth Army, had made systematic arrangements for the liberation of prisoners as rapidly as possible;40 seventy recovery teams had been organized and assigned to the Sixth and Eighth Armies and the XXIV Corps. In addition, nine liaison teams, in which the British, Canadian, Australian, and Netherlands Governments were represented, were attached to army and corps headquarters.

After V-J Day, teams were immediately dispatched to prison camp areas in Japan where they released, processed, and arranged transportation for 32,624 prisoners of war, all of them liberated within a period of three weeks.41

The Recovered Personnel Section (28 teams) arrived in Yokohama on 30 August 1945 with the advance airborne echelon of Eighth Army Headquarters.42 Advance planning proved invaluable in coordinating airdrops of food, clothing and medical supplies for immediate relief to the prisoners; although some changes became necessary since the Japanese had made extensive transfers of prisoners after 30 June 1945.43 It should be noted that there were also

[102]

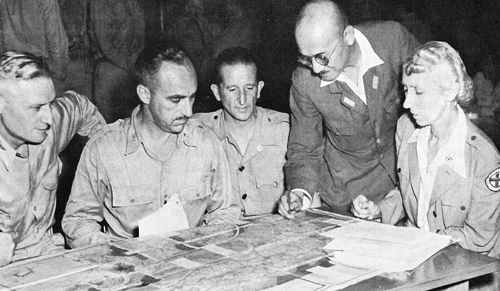

PLATE NO. 33

Red Cross Duties, September 1945

[103]

many internees confined in places other than prisoner of war camps.44 The accuracy of PW strength figures was further reduced by wholesale movements of Allied PW's from camps in heavily bombed coastal areas. To add further to the confusion, the Japanese Government had placed restrictions, despite vigorous protests, upon the activities of representatives of the Swiss Government and the International Red Cross Committee. This action made it more difficult for the American authorities to have a full and accurate picture of the conditions under which many prisoners were held by the Japanese. Most civilian internees were held in camps which were visited by neutral representatives, but practically nothing was known of the whereabouts or welfare of military personnel who were held in camps which the neutral representatives were not permitted to inspect.45 Soon after the Occupation began, the Japanese Government reported to SCAP that there had been ninety-four PW camps in Japan. Noticing that several camp names in the affidavits from former prisoners were not among those listed, the Chief of Legal Section's Investigation Division sent out investigators to comb Japan. They returned with the names and locations of thirty-three additional PW camps, including the infamous Ofuna camp and interrogation center operated by the Japanese Imperial Navy.46 As revised information about locations and needs of individual camps reached the Recovered Personnel Subsection, it was compiled and passed on to FEAR Such information brought prompt action: planes went swooping over freshly located Japanese prison stockades to drop food and supplies often on the very day the new locations were reported. (Plate No. 33)

An American surgeon, inmate of one of these camps gave a graphic account of the reactions of the prisoners of war:47

Six tiny black specks appeared in the sky. Flying low over rugged mountain ranges, these planes wove back and forth in single file, following the course of the river. At a height of five thousand feet they roared over camp.... Three hundred ragged prisoners ran up and down the little compound waving their arms hysterically and yelling themselves hoarse, trying to attract their attention. On the roofs of the barracks we had painted in huge orange letters "P.O. W.", on a black background. We had laid out gray blankets forming the same letters on a strip of white sand outside the camp....The flyers missed the signs, covered by the heavy ground mist which settled over the tiny valley in the early morning.

[104]

They disappeared over the horizon as we moaned and cussed. An hour later we heard the drone of motors in the west. They appeared again, lower this time, their black wings shining in the morning sun. Down through a cleft in the mountain range the flight leader dove straight for the enemy camp, waggling his wings. We howled, cheered, and pounded each other. Tears of joy streamed down our faces. Hearts thumped with happiness as we saw the white star in its blue circle on the wings of the plane.

The planes followed one after another at a level of a thousand feet. They circled round and round the hidden valley, checking wind currents and trying various approaches to the little camp. Finally the flight leader made his run, clearing the pine trees on the overhanging mountain range by feet. Down he dove steeply to a level of three hundred feet above camp. A black object hurtled down from the plane; an orange parachute fluttered open. A suspended fifty-five-gallon drum pendulumed back and forth three times and dropped with a thud in a clearing fifty feet square, between the Nip administration building and the galley-a bull's eye! The plane pulled out of its dive, clearing the barracks, and climbed rapidly to top the opposing hills. One after another the planes roared down and dropped their loads. One food packet landed in the doorway of the galley. The parachute of another failed to open. Its drum plummeted to the ground and buried itself deeply in the mud near the bank of the river. Something red fluttered down. The men high-tailed it. There was a note stuck in a sandbag which had a long, red cloth streamer. It read: "Hello, Folks: The crew of the U.S.S. Randolph send their best. Hope you enjoy the chow. Keep your chin up. We'll be back."

Our first contact with American forces in three and a half years ! ...

Liberated prisoners were taken from camps in the interior to Yokohama where hospital ships, billeting accommodations, and food supplies were available. Twenty-eight specially trained AFPAC recovery teams, each composed of an officer and three enlisted men, were attached to the Eighth Army for this mission.48 Some of the teams moved into the interior before demilitarization of the Japanese armed forces, in order to seize camp records before they could be destroyed by camp commanders. Diaries, records of deaths, and information on atrocities (later used in the trials of war criminals) were seized by these teams. Other recovery teams boarded Navy vessels to aid in evacuation of camps near the coast.49

Eighty-six Red Cross field men arrived with the first occupation troops, and four Red Cross girls attached to the 42d General Hospital arrived in Tokyo Bay on the USAHS Marigold.50 These American Red Cross repre-

[105]

sentatives were among the first visitors from the outside to talk to prisoners of war at Kawasaki camp Number 1, where medical care was most critically needed. Most of the prisoners captured earlier at Guam, Bataan and Corregidor had been imprisoned for more than three years. Many of them had died from abuse and hunger and deprivation during their long confinement; however, those who had survived were in a slightly improved condition, due to the earlier air drops of food, clothing and medical necessities.51

In camp Number 3 at Maibara, sixty-five miles northeast of Osaka, the prisoners had spent their noon hours diving for mussels to provide the only nutritious food obtainable during their long imprisonment; as in all the other camps, they had been forced to sustain life on watery soup, scanty greens, and barley gruel. Mount Futabi Camp, near Kobe, contained civilian workers who had been taken prisoner at Guam and had been interned for three and a half years.52 United States veterans of Wake Island and Bataan also emerged from these Japanese prison camps. They listened dazedly to the conversation of the American medical men who cared for them. Buried in prison camps for three years, they had no idea that the United States had twelve million men under arms and that Germany had surrendered. Not even the name of Harry Truman meant anything to them. They listened to unfamiliar expressions and names of battles, planes, and army units about which they knew nothing. Year after year, men had vanished into Japan without a trace-the men of Singapore, of Hong Kong, of Bataan, of Wake, of the ships sunk at sea, and of the planes shot down in combat. Only a few had received Red Cross packages; practically all their guards had engaged in graft; they had been beaten and kicked, had been forced to bow and to obey endless petty rules invented by their captors.53 For stubbornly rebellious prisoners and airmen from whom the Japanese hoped to extract information there was a special treatment. They were sent to Ofuna, a camp for unregistered prisoners, where they endured months of solitary confinement and torture.54 The fate of prisoners who became sick was hardly better.

[106]

Lt. Gen. Tamura, Japanese PW Intelligence Bureau, points out camps to Col. R. R. Coursey,

G-1, GHQ, Col. A. E. Schanzie, G-1, Eighth Army, and IRC delegates Dr. M. Junod and M. Strahler.

At Atsugi Airfield, Allied prisoners of war released from Toyama Camp bring letters to the American

Red Cross table for postage and mailing back home.

PLATE NO. 34

Red Cross Duties, September 1945

[107]

The majority of these men, when sent to the dirt-floored buildings of Shinagawa, lone hospital for 8,000 prisoners near Tokyo, simply went to their deaths.55 There was a complete lack of sanitation. Patients slept on flea-infested mats without blankets. The operating tables were bare boards. A number of the prisoners died as a result of being used as guinea pigs for incredible experimentation.56

Prisoners were promptly evacuated from camps where these appalling conditions existed to relay points from which they could be sent to processing centers and then home. In order to bring in necessary ships for loading, mine sweepers were ordered in to clear the various ports used. Ambulances, trucks, food and medical supplies were rushed to the various loading areas. Principal landing places were Kochi for Shikoku, and Omuta in Shimbara, Kaiwan for Kyushu and western Honshu camps,

[108]

except Kagoshima and Nagasaki which were accessible locally.57 After 1 September the movement of prisoners was rapid, and on 6 September General Eichelberger requested evacuation and processing facilities for 1,600 prisoners of war at Hakodate and for 3,802 at Sendai.58 On 10 September eight Allied ships arrived in Shiogama and began loading personnel for evacuation early the following morning.59

After years of unbelievable suffering, released prisoners of war often had their former Japanese captors at their mercy, since control of each camp was turned over to a senior officer or civilian prisoner. To their everlasting credit, most of the prisoners refrained from revenging themselves. In several instances, some of them did all in their power to aid those Japanese who had shown them kindness during their long period of confinement. Many of them gave articles of food and clothing from their own inadequate supply to their former jailers.60

To supplement the work of the Recovery Teams, the Eighth Army Surgeon organized four medical teams which were sent to various camp areas to care for the sick and alleviate suffering. These arrived in Yokohama, from Okinawa, on 30 August 1945. After physical examination, the prisoners were formed into groups and escorted to Yokohama. One team was assigned to Navy Task Force 36 and made two mercy trips, utilizing the USNHS Rescue for hospital cases. The first mission covered the Hamamatsu area near Nagoya, where approximately 3,850 prisoners were processed; 15 percent of them required hospital care and prisoners The second troop covered the Sendai Kamaishi area, where about 3,000 were found.61

A second team proceeded to the Kobe area by rail and established headquarters in Kobe Prison House Number 2. This territory had originally been assigned to Sixth Army, but due

[109]

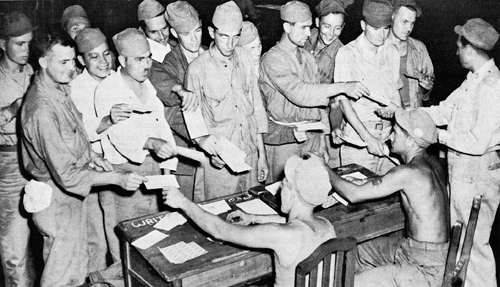

Prisoner of war, newly arrived at Yokohama Central Station, is carried to

an ambulance by medics of the 1st Cavalry Division, XI Corps.

Recently arrived prisoners of war relax outside a warehouse on docks at Yokohama.

PLATE NO. 35

Released Prisoners of War, 5 September 1945

[110]

to the urgency of the situation, areas assigned to Eighth Army were extended in order to bring speedy relief.62 By 7 September the team had cleared 7,500 evacuees from thirteen camps in the vicinity and had them en route to Yokohama. This group also handled all litter cases from the International Committee of the Red Cross in Kobe, where the Japanese had collected the seriously ill patients from the nearby stockades. Ninety percent of these patients were in advanced stages of tuberculosis.63 Processing in the Kobe area was completed by a third team which evacuated approximately 6,900 prisoners from 6 to 20 September.

The fourth team operated from 10 to 20 September and processed 1,600 prisoners in five separate camp areas on the island of Hokkaido. Traveling thence from Yokohama, they were the first Americans to land on an airstrip near Chitose City. Headquarters of the team were set up in the Chitose Naval Air Training Base, and all evacuees were transported to Yokohama by plane.64

In the turmoil of the first days of the Occupation, one of the earliest of many conferences at Headquarters (Yokohama) was held by the Eighth Army Surgeon on 1 September 1945. In this meeting plans were perfected for evacuating prisoners of war who required hospitalization and evacuation. It was decided that all recoverees should be screened by the medical staff of USAHS Marigold, anchored in Yokohama harbor. The repatriates were classified in three categories: (1) Those found to be acutely ill and requiring extended hospitalization were to be assigned to the Marigold for direct transportation to a hospital in the United States. This group was to include United States service and civilian personnel and Canadians if they so desired. (2) Those who were found to be not only acutely ill, but also in need of a period of rehabilitation were to be

[111]

transferred to a hospital ship (possibly the USNHS Rescue) for transportation to the Marianas Islands for the required period of rehabilitation. (3) Ambulatory cases not requiring hospitalization or treatment were to be flown to various points, as indicated by results of the screening process.65

Processing for Home: Before the above plan could be launched, circumstances of rapid evacuation of the camps necessitated some revisions. The 42d General Hospital, which had arrived in Tokyo Bay on August 1945 aboard the Marigold, assumed the processing of liberated PW's and civilian internees.66 Facilities were established for this purpose in warehouses in the Yokohama dock area on 3 September, and twenty-four hours later the first group of evacuees went through the processing routine. Despite the three types of processing involved-medical, factual, and dispositional-this famous hospital unit eventually was able to handle three persons per minute.

Four phases made up the processing routine. Upon arrival at the Yokohama Central Station, the former prisoners found that every effort was made to make them feel at home. General Eichelberger was there as often as possible to extend his warm personal greetings67 The welcoming committee, composed of a group of officers and nurses, distributed candy, cigarettes, and other luxuries to the arrivals and escorted them to the hospital area. A division band from either the "Americal" or the 1st Cavalry was on hand to brighten the occasion with popular American tunes. After the evacuees reached the hospital area, all undesirable equipment and clothing was discarded; salvageable articles were sent to the Quartermaster Depot. A hot, substantial meal was served to all incoming groups, a measure of practical psychological value, inasmuch as most of them had been traveling from fourteen to sixteen hours without food. During several twenty-four-hour periods in these busy days, the mess served as many as 3,500 meals.68

After this reception, evacuees were taken to a decontamination room where they disrobed completely. Each individual was then required to take a shower, while at the same time his clothing and personal effects were sprayed with DDT. An army nurse interviewed each one, recorded his temperature, pulse, respiration, and complaints, as well as other personal data. A complete physical examination followed. Non-patients were given an issue of new clothing and proceeded to the General Headquarters processing area, where the required War Department data were obtained. They were then classified for various types of evacuation, according to status. Litter cases were carried to a separate area, served a meal, disrobed, bathed, given a physical examination and admitted directly to a hospital ship.69 War

[112]

Department data were obtained from these individuals by supplemental processing teams aboard the hospital ships. As passenger manifests were made up, each group was evacuated by air or water. All ambulatory cases left Japan within twenty-four hours of arrival in Yokohama.70

Radio reports were prepared daily and sent to Commander in Chief, Army Forces Pacific, Tokyo; Commander in Chief, Army Forces Pacific, Manila, and the Adjutant General, Washington, which meant that relatives in the United States and in other United Nations were usually given the news of recovery within a few days. Machine records showing the nationality, branch of service, date and place of recovery, and physical condition were made. These rosters enabled many servicemen of the Allied Powers to gain information that relatives and former comrades were alive and had been freed from the prison camps. Copies of this roster were furnished to Commander in Chief, AFPAC Advance, in Tokyo, the U. S. Navy, and the Marine Corps. One copy went to representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross for transmittal to Geneva.71

A grand total of 17,531 prisoners and internees were processed through the 42nd General Hospital during the eighteen-day period it operated in this capacity. The evacuees included people from the United States, Great Britain and Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, the Netherlands, Greece, France, Spain, Iceland, Finland, Italy, Malay, Guam, China, Norway, Hawaii, Czechoslovakia, Mexico, Burma, Poland, Malta, and Portugal.72

The 608th Medical Clearing Company (Sep), under directions of the Eighth Army Surgeon, served as a holding station at Atsugi airfield and arranged for air transportation. Americans and Canadians were flown to Guam, Saipan, or Manila.73 Nationals of other countries went by air to Okinawa, and from there flew to Manila. Rapid preparation of passenger lists and coordination with the Air Transport Command made it possible to fly as many as 1,600 individuals in one day by C-54's from Atsugi to Okinawa and thence to Manila.74 Similar numbers were evacuated to Guam aboard U. S. Navy vessels. By 21 September the processing of prisoners of war and civilian internees had largely been completed and the 42d General Hospital ceased operations as the processing agency. This work was then assumed by the 608th Medical Clearing Company (Sep) and the 30th Portable Surgical Hospital, both located at Atsugi airfield, but relatively few recoverees remained to be taken care of.75 In all, the Eighth Army freed and evacuated 23,985 persons.76

[113]

Procedure Regarding Dead and Missing

Prisoners of War

All former prisoners of war camp sites were examined. During the investigation of these camps, Japanese officers, doctors, and employees of mining companies were interviewed. Records and documents were secured. They included lists of prisoners, reports on prisoners who had died at the camps, hospitalization reports, authorization to dispose of bodies, receipt for ashes of those who had died and had been cremated, photographs of camps, camp regulations, employment of prisoners, food, clothing, housing, and general welfare. Effort was made to determine cause of death and to obtain a full report if death was not due to natural causes. In one instance it was learned that thirty-two prisoners of war were killed or died as a result of shelling and bombardment by the Allied Navy. In many instances it was found that available records and documents had been removed when the prisoners were released.77

On 30 September 1945 SCAP issued a memorandum to the Imperial Japanese Government regarding regulations of prisoners of war. The memorandum directed that articles and money of the dead prisoners, whether possessed by the military personnel in charge of camps, government offices, hospitals, or dressing stations, must be sent to the Prisoners' Information Bureau. It demanded a prompt report as to what action had been taken to secure the personal property of all deceased prisoners. The report was also to include evidence of funds, such as credits for money held by or on deposit with any agency or representatives of the Imperial Japanese Government;78 and all sums due but not paid to a prisoner of war for services rendered prior to his death. In the event that the above outlined action was not taken regarding a deceased prisoner's property, it was to be marked to show the prisoner's name, rank, serial number, nationality and branch of service, as well as the name of the camp where he had been confined. The belongings were then to be delivered to the headquarters of the major Allied military force occupying the zone or district where the items were found. After delivery was made, a report was to be sent to SCAP. This report was to include a roster showing all information listed above for every deceased prisoner of war and civilian internee.79

In a further effort to account for all missing prisoners of war, not located in camps by the recovery teams and not listed among the dead in camps, the Adjutant General's Office sent another memorandum to the Imperial Japanese Government on 26 November 1945 requesting additional information.80 Recovery teams also attempted to acquire all possible information on deceased prisoners who had been cremated. The customs of the Japanese did not allow for the proper burial of the dead, and consequently the problems were much greater than anticipat-

[114]

ed. The varied problems confronting the Quartermaster Section in this task included the investigation of prisoner of war camps, the recovery of air crashes; and the disposition of the remains of all deceased persons. Diaries of prisoners, conferences with prisoner camp commanders, and interrogations of other Japanese were chief sources of information for lists of the dead and their location. For personnel not accounted for, further investigation was carried on by Graves Registration personnel.81 This search for the dead was carried out simultaneously with the evacuation of the living.

Final Processing of Prisoners of War

in Manila

Evacuees from Japan were processed in Manila before leaving for home. From the moment these former prisoners came under the control of American forces everything possible was done to add to their comfort. They were given an enthusiastic and warm welcome, and an attempt was made to comply with all of their requests.

The mission of receiving, processing, and looking after these people was given to the Replacement Command. Here recreation programs, a central registration file, and communication centers were established. Messages from home were delivered as quickly as possible.82 British, Australian, and Canadian male personnel and later the Dutch were assigned to the 5th Replacement Depot; women, children, and family groups were sent to the Women's Replacement and Disposition Center for processing. To provide adequate medical facilities and care for recovered Allied military personnel, a 1500-bed general hospital was attached to the Replacement Command. In addition, two infirmaries and a number of dispensaries were operated in two reception centers near Manila. A medical processing group was set up at Nichols Field for the preliminary separation of former prisoners into two groups: those needing hospitalization and those able to proceed directly to the depots.

Five thousand beds were held in reserve in the Manila area, 500 of them for women and children at the 12oth General Hospital at Santo Tomas University, and the remainder at the Mandaluyong Hospital Center. A total of 2,000 beds were also held in reserve at bases in northern Luzon. These bed credits were based upon the assumption that 45,000 freed persons would be processed through the Philippines. The allotment proved to be more than adequate.83 Clothing, equipment, and post exchange supplies were issued free; well earned promotions were given and decorations awarded; accrued pay accounts were settled; and entertainment and Red Cross recreation activities were provided. By utilizing air travel to the greatest possible extent, transportation to their homes was arranged with little delay.

Of the 28,786 evacuees received by 30 September 1945, 12,286 were repatriated. From October to December approximately 3,000 additional persons arrived. By this time repatriation shipments had progressed so satisfactorily that by the end of October there remained only a few hospital cases, together with 6,529 Dutch personnel. The latter remained only because of the uncertain political situation in the Netherlands East Indies. By

[115]

the end of the year a total of 31,879 former prisoners had been processed with but a few hundred still under the jurisdiction of the Replacement Command.84

Thus, in the short period of four months, most of the Allied prisoners of war and civilian internees had been restored to their families. Through careful preparation, the efficient execution of plans, and the full cooperation of all personnel concerned, "Blacklist's" rescue mission proved most successful.

[116]

Go to

Last updated 11 December 2006 |