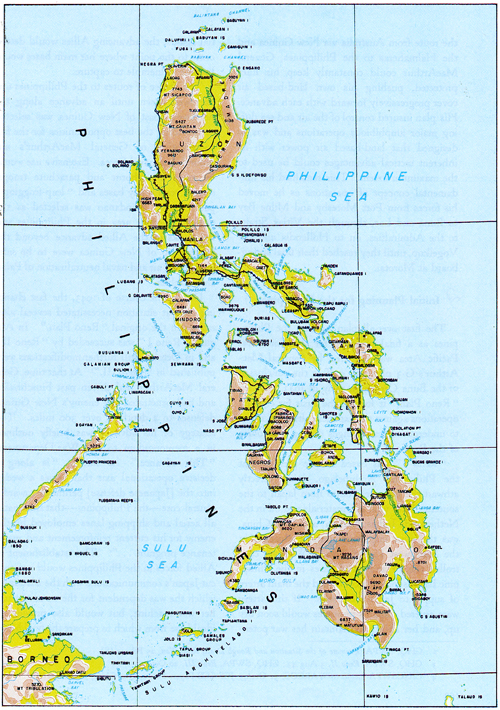

CHAPTER VII The Philippine Islands constituted the main objective of General MacArthur's planning from the time of his departure from Corregidor in March 1942 until his dramatic return to Leyte two and one half years later.1 From the very outset, this strategic archipelago formed the keystone of Japan's captured island empire and therefore became the ultimate goal of the plan of operations in the Southwest Pacific Area. (Plate No. 48) After the Philippines were liberated, they would form the main base for the final assault against the Japanese Homeland. As the Allies advanced westward along New Guinea and across the Central Pacific, a wide divergence of opinion developed among international planners and military strategists on the methods of defeating Japan, but General MacArthur never changed his basic plan of a steady advance along the New Guinea-Philippine axis, from Port Moresby to Manila. This plan was conceived as a forward movement of ground, sea, and air forces, fully co-ordinated for mutual support, operating along a single axis with the aim of isolating large Japanese forces that could be attacked at leisure or slowly starved into surrender. By choosing [166] PLATE NO. 48 [167] the route from Australia via New Guinea and the Halmaheras to the Philippines, General MacArthur could constantly keep his lines protected, pushing his own land-based air cover progressively forward with each advance. His plan insured control of the air and sea during major amphibious operations and was so designed that land-based air power with its inherent tactical advantages could be used to the maximum extent. This remained his fundamental concept of operations as he moved his forces from Port Moresby and Milne Bay to Buna and Lae, through the Vitiaz Straits to the Admiralties, on to Hollandia and the Vogelkop, until they reached their final springboard at Morotai. Initial Planning for the Philippines The first over-all plan naming the Philippines as a final objective for the Southwest Pacific Area was prepared by General MacArthur's G-3 planning staff at the conclusion of the Buna Campaign early in 1943. Called " Reno Plan," it formed the basis for ensuing operations against the Japanese although it was to undergo several changes during the course of the Pacific War. " Reno I " was based on the premise that the Philippine Archipelago, lying directly athwart the main sea routes from Japan to the sources of her vital raw materials and oil in the Netherlands Indies, Malaya, and Indo-China, was the most important strategic objective in the Southwest Pacific Area.2 Whoever controlled the air and naval bases in the Philippine Islands logically controlled the main artery of supply to Japan's factories. If this artery were severed, Japan's resources would soon dry up, and her ability to maintain her war potential against the advancing Allies would deteriorate to the point where her main bases would become vulnerable to capture. The choice of routes to the Philippines was narrowed down until an advance along the northwest coast of New Guinea was selected as providing the best opportunities for the full coordination of General MacArthur's air, ground, and naval forces. Extensive use would be made of airborne and parachute troops, seizing certain key bases and " leap-frogging " past others. Mindanao was selected as the tactical objective area in the Philippines and the flanks of the Allied advance beyond the western tip of New Guinea were to be safeguarded by air and naval neutralization of Palau and Ambon. During the course of 1943, the fast changing combat situation necessitated several alterations in the original " Reno Plan." In August, " Reno I " was succeeded by " Reno II " and in October still further modifications were published in " Reno III."3 At that time, General MacArthur had driven past Finschhafen and had penetrated the enemy's New Guinea defenses to a depth of over 300 miles. The strategy of his advance was briefly outlined in a memorandum to the War Department. " This advance," he stated, " is along a decisive operational axis that drives a wedge into the [Japanese defense] perimeter toward a central core-the Philippines-that dominates all aerial and shipping lanes employed by the enemy for his current reinforcement and maintenance program. . . ."4 The establishment of Allied forces in the Philippines would not only cut Japan's communications with the islands on which she was dependent for the means to run her war machine, but would also provide an ideal base from which to prepare the final blows [168] against Tokyo itself. General MacArthur continued his analysis with an appraisal of the various approaches to the Philippines. He considered that an attack from the Southeast Asia Command would be fontal in nature, pushing the Japanese back upon successive lines of defense which they could readily keep supplied. " A major effort along this line of action," he concluded, " is undesirable both tactically and logistically." An attack across the Pacific would also have to be delivered against a position organized in great depth. It would have to be supported entirely by carrier-based aircraft as opposed to land-based air cover, and it would not sufficiently cut the enemy's lines of communication nor seriously curtail his war potential.5 A drive from the Southwest Pacific Area, on the other hand, possessed several advantages which General MacArthur explained as follows:

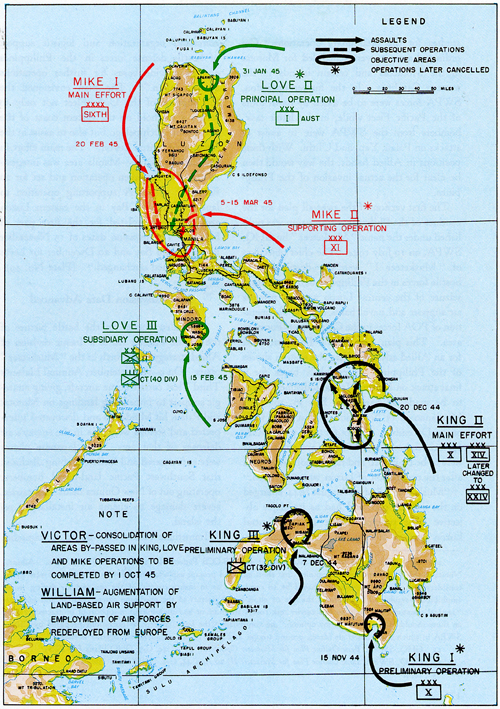

He agreed that if the forces were available it would be advantageous to attack in force along each line of advance, but he maintained that the paucity of means in the initial stages, particularly in amphibious craft, should limit the Allies to a single drive in full strength. " To attempt a major effort along each axis," he stated, "would result in weakness everywhere in violation of cardinal principles of war, and would result in failure to reach the vital strategic objective at the earliest possible date, thus prolonging the war." Concentration on the most advantageous route of advance, with a powerful drive forward, was in General MacArthur's view the surest way to an early victory.7 By March of 1944, SWPA forces had landed in the Admiralties and Central Pacific forces had won positions in both the Gilberts and the Marshalls. Parallel drives converging upon the Philippines and Formosa from both the Southwest Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas appeared to be possible. The strategic objectives, set forth under a new " Reno IV " plan, were expanded to include the securing of land, naval, and air bases in the southern Philippines from which to launch an attack upon Luzon in the north. Bases in Luzon would in turn be used for the support of subsequent Allied assaults against the Formosa-China coast area.8 The spring and summer of 1944 saw accelerated action in the war against Japan as the Allied advance gathered greater momentum. In the latter part of March, naval task force strikes were carried out against Palau, Yap, and Woleai, and at the end of April a heavy and damaging carrier raid was made on Truk. SWPA forces meanwhile invaded Aitape and Hollandia and during May assaulted Wakde and Biak. On 15 June, Central Pacific forces invaded Saipan in the Marianas to begin construction of a base for the mighty B-29 bombers. The Allied forces were fast reaching tactical positions from which to launch a powerful offensive into Japan's main lines of defense. [169] Again the question arose as to the best points of attack and the most advantageous routes of approach. Various proposals were put forth for bypassing certain previously planned objectives or for by-passing all objectives short of the Japanese Home Islands themselves. Other plans advocated the use of long-range bombing from the Marianas to force the Japanese into surrender. Still others considered bases in China necessary to accomplish the task, with landings to be made along the China coast from positions in the Philippines. The suggestion was made that western New Guinea, Halmahera, and the Palaus be by-passed for an immediate blow at the Philippines; another plan advocated the capture of airfields in the southern Philippines and then striking directly at Formosa; and finally, a proposal was put forth to take the Philippines as a base for an assault straight into Kyushu, the southernmost of the four Japanese Home Islands. Certain of these proposals were discarded upon further study as entailing too great a risk, with the possibility that failure would delay the conclusion of the war by many months. Other suggestions appeared to be more time-consuming and costly in men and materials than substitute objectives which might be found. The plan to force Japan to surrender by strategic bombing would undoubtedly require supplementing with actual territorial conquest of numerous vital areas. Throughout the strategic planning on ways and means to defeat Japan, General MacArthur held firmly to his original concept. In view of the over-all situation in the summer of 1944, he considered that the route through Halmahera and the Palaus into the southern Philippines, and thence to Luzon was the most feasible approach to the Japanese Homeland. It permitted an advance that could move under the cover of land-based air power from start to finish, with a minimum of risk and with every assurance of success. This route would also take advantage of the large Philippines guerrilla forces which were already furnishing valuable intelligence and which were waiting impatiently to assist in ousting the enemy. Aside from military considerations, moreover, the liberation of the Philippines was a duty that General MacArthur felt had to be fulfilled as soon as possible. He outlined his views in a radio to the War Department a few days after completing the final draft of his "Reno V" plan:

General MacArthur's views regarding the approach to the Philippines met with general acceptance, and early in July 1944, joint staff conferences were held with representatives of the Central Pacific Area to prepare detailed [170] PLATE NO. 49 [171] studies for the preliminary operations.10 Coordinated assaults were scheduled for Morotai in the Moluccas and certain islands in the western Carolines. In the former operation, SWPA forces were to be aided by naval units of the Pacific Fleet while, in the latter task, bombers from the SWPA were to assist in attacks on Palau, Yap, and Ulithi. With these positions in Allied hands, the way would then be clear for the actual invasion of the Philippines. The first version of the over-all plan for the conduct of the Philippines Campaign was published under the name " Musketeer " by GHQ, SWPA, on 10 July 1944. The chief objectives of " Musketeer I " were the destruction of hostile forces in the Philippines and the prompt seizure of the central Luzon area to provide air support and naval bases for possible operation of POA forces in the China coast-Formosa area. This plan, like " Reno IV, " provided for an Allied advance along the eastern shores of the Philippines to establish bases for a final attack on Luzon. Initial lodgements were to be made at Sarangani Bay in southern Mindanao on 15 November and at Leyte Gulf on 20 December. Except for these preliminary operations, however, Mindanao and the Visayas were to be by-passed and not consolidated until after the occupation of Luzon was completed.11 "Musketeer II " of 29 August 1944, enlarged on the original plan and had as its major objective "the prompt seizure of the Central Luzon area to destroy the principal garrison, command organization and logistic support of hostile defense forces in the Philippines and to provide bases for further operations against Japan."12 The plan envisioned the full support of the U. S. Fleet not only to secure a foothold on the eastern coast of the Philippine Archipelago but also to assist in the invasion of central Luzon. The main effort in the Central Plains-Manila area was integrated into the Lingayen operation and set for 20 February 1945. A supporting operation to land at Dingalen Bay in the eastern Luzon area was contemplated for the first part of March. The invasion dates of 15 November for Sarangani Bay and 20 December for Leyte Gulf remained unchanged.13 (Plate No. 49) A sudden change in the battle picture of the Pacific Theater led to a drastic revision of Allied strategy as set forth in the " Musketeer " plans. On 9-10 September, Admiral Halsey's Third Fleet carrier-borne aircraft, giving strategic support to impending landings on Morotai and Palau, hit Mindanao and discovered unexpected and serious weakness in the enemy's air defenses of that area. Few Japanese planes were encountered and further probing disclosed that Southwest Pacific land-based bombers, operating out of New Guinea fields, had caused severe damage to enemy air installations on the island. Immediate orders were issued to capitalize [172] on the enemy's apparent aerial weakness. The Allies moved on beyond Mindanao and carrier task groups of the Third Fleet sortied northward to hit the Visayas on 12 and 13 September. Again enemy air reaction was surprisingly meager and heavy loss was inflicted upon Japanese planes and ground installations. It became more and more apparent that the bulk of the once mighty Japanese Air Force had been destroyed in the costly war of attrition incidental to the New Guinea operations. The disclosure of such great vulnerability in the enemy's air shield over the Philippines caused an immediate reassessment of the situation to ascertain whether an acceleration of the existing schedule would be possible by omitting certain previously planned operations designed mainly for air support. Intelligence sources indicated that the Japanese had been increasing their ground forces in the Philippines.14 With the enemy thus strengthening his positions to meet the anticipated Allied assaults, each month or week that could be cut from the Allied timetable for the Philippines would accordingly reduce the over-all cost of the campaign and help ensure its rapid accomplishment. On 13 September Admiral Halsey advised Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur that he believed the seizure of the western Carolines, including Palau, was no longer essential to the occupation of the Philippines.15 He suggested that Leyte could be seized immediately if all projected operations in the Carolines, with the exception of Ulithi, were cancelled and the landings were covered by carrier aircraft. Admiral Nimitz concurred in the proposal to by-pass Yap, but directed that the Palau and Ulithi operations be carried out as scheduled, the former being needed as an air base and the latter as a fleet anchorage.16 Admiral Halsey's recommendation was relayed to the Joint Chiefs of Staff who were then participating in the Quebec Conference between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill. General MacArthur's views were requested on the proposed change of the invasion date for Leyte and the reply came back as follows:

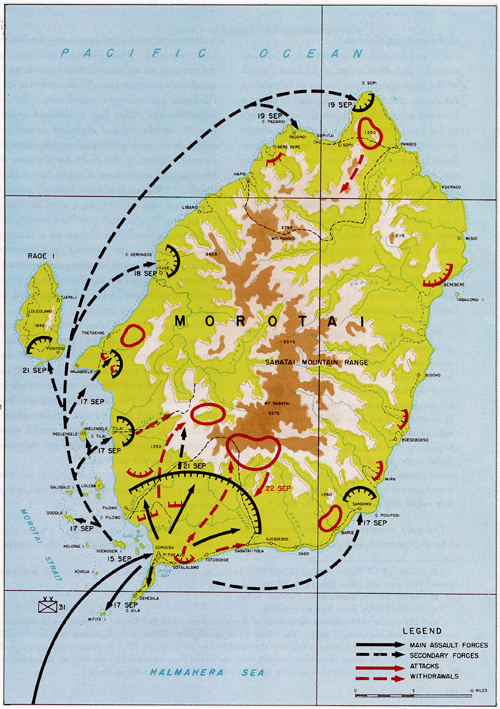

The advance planning and the preparation of alternative solutions which were standard operational procedure for General MacArthur's staff, again, as in the case of Hollandia, permitted the necessary flexibility for rapid change. Accordingly, with the assurance that the SWPA forces could conform to the proposed change in schedule, the target date for the Leyte landing was advanced fully two months ahead of the original schedule.18 [173] Other important decisions were made in rapid order. Preliminary operations, such as the seizure of Talaud, Yap, Misamis Occidental, and Sarangani, were cancelled. The Palau and Morotai operations, still considered necessary for air support and flank protection against thrusts from the Mandated Islands or from Halmahera and the Celebes, remained scheduled for 15 September. The landing on Ulithi, to secure a forward area logistic support base for the fleet, was planned for 23 September. The sustained air assaults of the Far Eastern Air Force against hostile bases in the Netherlands East Indies, together with Allied landings on Biak, Noemfoor, and Sansapor, had greatly weakened the enemy stronghold at Halmahera. His airfields there and at contiguous intermediate bases were almost wholly neutralized, his maritime forces largely interdicted, and his ground troops immobilized in almost static helplessness. The flexibility of the Halmahera base, from which he once funneled his forces to strategic outposts, was now completely destroyed. If he failed to retrieve his position, one of the main lines of defense protecting the Philippines and the Netherlands East Indies was gravely threatened.19 Intelligence sources revealed that, beginning in June 1944, the Japanese had displayed considerable interest in the defense of Morotai at the northern tip of Halmahera, but that little had been accomplished, presumably because other areas were placed higher on the list of probable Allied objectives. With its small garrison, Morotai offered an excellent opportunity for securing a base without prolonged fighting or heavy losses. It fitted well into General MacArthur's scheme of winning important positions by attacking weakly held but strategically valuable points. Additional information indicated that, while the Japanese strength on Morotai was relatively weak, the island could be substantially reinforced by barge and transport traffic with troops from Halmahera within forty-eight hours and from the Philippines within a week.20 The full weight of Allied air power was thrown against the Japanese to forestall any reinforcement efforts. Medium and heavy bombers of the Southwest Pacific Area struck airdromes on Mindanao, Halmahera, and the Netherlands East Indies, while fighters attacked and strafed defense installations, shipping, and troop concentrations. The fast carriers of the Third Fleet hit Chichi Jima and Iwo Jima in the Bonins, and Mindanao and the Visayas in the Philippines, with repeated raids between 31 August and 14 September. Hostile aircraft were confined to the northern Philippines and [174] PLATE NO. 50 [175] to the southern Celebes.21 Air and naval bombardment of shore positions on Halmahera, as well as Morotai, preceded the landings at Pitoe Bay on 15 September. An Alamo task force was composed of the 31st Division and 126th Regimental Combat Team of the 32nd Division plus supporting combat and service troops, directed by XI Corps. Seventh Amphibious Force convoys carrying the assault troops were protected by escort carriers and land-based fighters as they moved from Aitape and Toem. General MacArthur went with his troops and viewed the bombardment of Galela on Halmahera from aboard the cruiser Nashville and later went ashore on one of the beachheads. A description of the landing appeared that day in the communiqué of the Southwest Pacific Headquarters:

The main objectives on Morotai were reached by 16 September, and ground activities were limited to mopping up and extending the beachhead perimeter. (Plate No. 50) Air warning systems were set up, beach defenses coordinated, antiaircraft weapons brought into position and PT boats put on night patrol duty. By 21 September the Allies had established a firm position on Morotai and work was started immediately on facilities for pushing the offensive forward. Viewing the rapid development of Morotai with satisfaction, General MacArthur stated: '' We shall shortly have an air and light naval base here within 300 miles of the Philippines."23 An airstrip at Pitoe was opened operationally for fighter aircraft on 4 October and on that date the Morotai operation was officially terminated.24 Mopping up operations, however, were carried out for a long period against a stubborn enemy who continued to land troops by barge traffic. Strategically the Halmahera-Philippines line had been penetrated and the enemy's conquests to the south imperiled by an imminent threat of Allied envelopment. The rolling up of the remainder of this line would cut off in the Netherlands East Indies the Japanese Sixteenth and Nineteenth Armies, a force estimated at nearly 200,000 men, and would sever essential supplies of oil and other war materials from the Japanese mainland. General MacArthur commented on the enemy and the future trend of the war in the following words:

[176] PLATE NO. 51 [177]

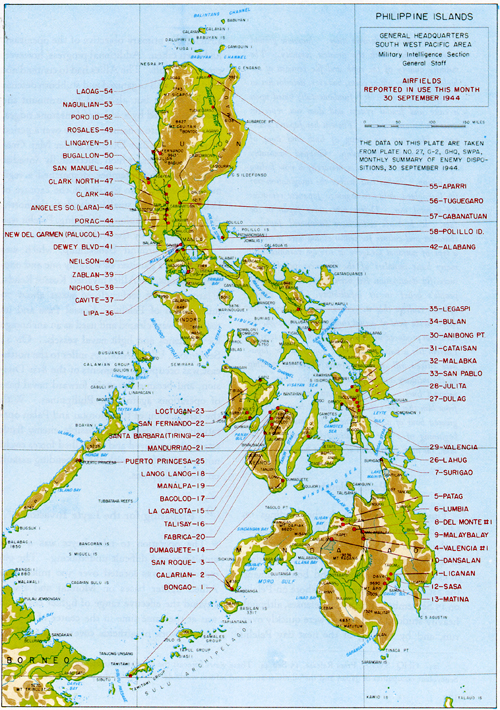

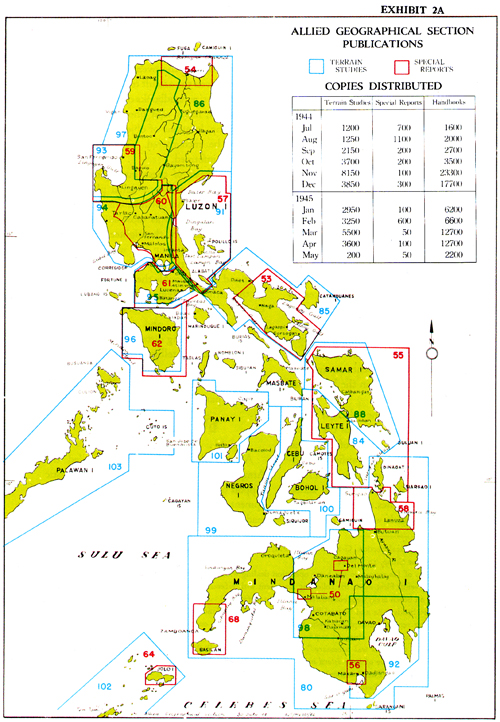

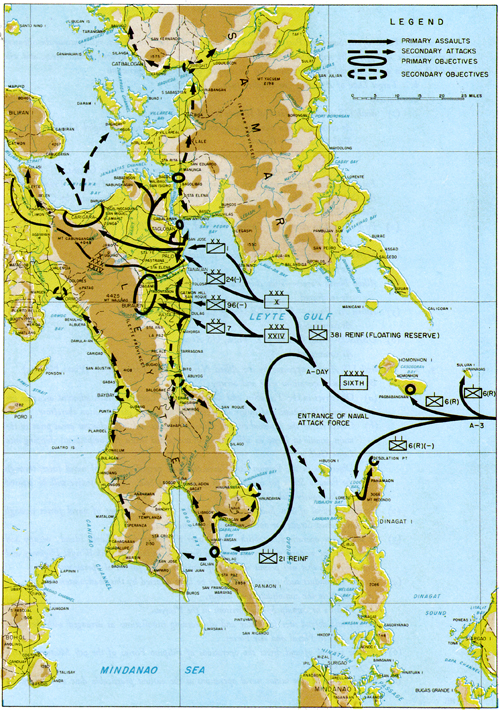

Timed to coincide with the landings on Morotai, assaults against Peleliu and Angaur in the Palau Islands were carried out by forces of the Central Pacific. Preceded by two days of extensive minesweeping and bombardment, the 1st Marine Division went ashore on Peleliu on 15 September. The beach defenses, although heavily studded with mines, were quickly overrun, and by evening of the next day Peleliu airfield, the primary objective of the operation, had been taken. Additional progress, however, proved difficult. The Allies had to contend not only with a well organized and stubborn defense by the enemy but also had to surmount the obstacles offered by a series of limestone ridges, transformed into a natural fortress over a period of years. The 81st Division under Maj. Gen. Paul J. Mueller, which successfully invaded Angaur on 17 September, dispatched a regimental combat team to assist in the capture of Peleliu and several smaller islands to the north. After heavy and prolonged fighting, Peleliu was finally subdued by the end of September. Sweeping around Babelthuap, which was defended by a garrison of roughly one and one-half divisions, the Allies invaded Kossol Roads, a large body of reef-enclosed water about 70 miles north of Peleliu. Kossol Pass and its roadstead were cleared and used as an anchorage for seaplanes and light naval vessels. On 23 September, Ulithi Atoll, 35 miles to the northeast, was occupied by elements of the 81st Division, and became the main forward naval base of operations against the Philippines. With the termination of the Morotai and Palau operations, the threat of a possible enemy flank attack was removed and the Allied forces could now proceed freely with the impending assault on the Philippines. Preparing for the Leyte Invasion The operation to take Leyte was a most ambitious and difficult undertaking. The objective area was located over 500 miles from Allied fighter bases on Morotai and Palau, beyond the effective range of fighter cover. It was at the same time in the center of a Japanese network of airfields covering the Philip- [178] pines. (Plate No. 51) The islands would doubtless be defended to the limit of the enemy's capabilities, probably even at the risk of losing his heretofore husbanded navy, since a successful Allied landing on Leyte would presage the eventual reoccupation of the entire Philippine area. The Japanese could reinforce their positions by bringing in troops and supplies from their rear lines whereas, without air bases in the vicinity, the Allied forces would have to rely on naval aircraft to prevent enemy supply and reinforcement convoys from reaching the area. Again, as at Hollandia, SWPA forces would advance beyond the range of their own land-based fighter cover and put themselves under the temporary protection of carrier planes for the assault phase. The success of the operation, even after a landing was secured, would depend on the ability of Allied naval forces to keep the enemy from building up a preponderance of strength on Leyte and adjoining Samar, and to prevent enemy naval craft from attacking shipping in the beachhead area. Careful study receded the selection of the landing beaches and the direction of the inland thrust on Leyte. A special report of the Allied Geographical Section detailing airfields, landing beaches, and roads was furnished to the planning staff months ahead of the actual invasion.26 Terrain studies covering all areas of the Philippines which were earmarked for invasion following Leyte gave necessary details on which to base the overall strategy. (Plate No. 52) Even the assault troops were supplied with pocket-size handbooks containing essential information, maps, and photographs on local topography, locations of objectives, and conditions to be encountered. The Allied forces were well informed. On the basis of these intelligence reports, confirmed by last minute aerial photographic reconnaissance, the northeastern coastal plain of Leyte was selected as most suitable for the assault.27 Seizure of the eighteen-mile stretch between Dulag and San Jose would permit the early capture of the important Tacloban Airfield and make possible the occupation and use of the airfield system under development at Dulag. It would permit domination of vital San Juanico Strait, and place the invading forces within striking distance of Panaon Strait to the south. Intelligence reports indicated that the beach area would not be heavily defended, although some fortifications were being prepared along the inland road net.28 An entirely new organization called the Army Service Command was set up for logistic support of the assault force and for base development and construction on Leyte. It was made a subordinate echelon of the United [179] PLATE NO. 52 [180] States Army Services of Supply, the organization which had furnished supplies to Allied troops in their drive from Australia to the Halmaheras. Maj. Gen. Hugh J. Casey, formerly General MacArthur's Chief Engineer, was given command of this new unit and directed to prepare and execute plans for the establishment and development of new bases in the Philippines in accordance with Services of Supply directives. Since the immediate problem was to develop an air base and transshipment port at Leyte, General Casey was instructed to plan and fulfill the combat logistical requirements for the operations of the Sixth Army after the Leyte landing was accomplished. To carry out this task as effectively as possible, the Army Service Command was put under direct control of General Krueger, meanwhile maintaining close liaison with Services of Supply from which it drew materiel and personnel.29 As soon as the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the advanced date of 20 October for the Leyte attack, the machinery for the organization of the vast task force was set in motion. (Plate No. 53) Under the original December invasion plan, it was intended that SWPA would furnish the entire troop complement necessary to carry out the assault. Australian forces were to take over combat responsibility in New Guinea and New Britain and free United States units for the Philippine action. The relief of the U. S. 37th and 40th Divisions in these areas, scheduled originally for October and November, could not be accomplished in time to meet the new target date. Consequently, the Central Pacific Area made the XXIV Corps available to General MacArthur as a substitute for these divisions. Southwest Pacific Area ground combat forces for the Leyte operation consisted of the X Corps, the major components of which were the 1st Cavalry and the 24th Infantry Divisions, both veteran units. This Corps was loaded on ships of Admiral Barbey's Seventh Amphibious Force, Task Force 78 of the Seventh Fleet, the same force which had so meritoriously conducted all previous major assault landings in the Southwest Pacific. Admiral Barbey's command was reinforced for the Leyte attack by shipping from Central Pacific sources. This augmented group, known as the Northern Attack Force, had the primary mission of landing the X Corps on beaches from Palo to Dulag on the eastern coast of Leyte. Part of the convoy carrying the X Corps Headquarters and Corps troops, the 24th Division, and the 6th Ranger Battalion, departed from Hollandia on 13 October. It rendezvoused on the 15th with the remainder of Admiral Barbey's fleet units which had carried the 1st Cavalry Division and reinforcing units from Manus Island.30 The XXIV Corps, less the 77th Infantry Division on Guam, had been combat loaded at Hawaii to be carried to Yap and Woleai by Vice Adm. Theodore S. Wilkinson's Third Amphibious Force, Task Force 33 of the Third Fleet. For the Leyte operation, Admiral Wilkinson's command was redesignated Task Force 79, the Southern Attack Force, and was transferred to the Seventh Fleet. The mission of the Southern Attack Force was to land and to establish the XXIV Corps, including the 7th and 516th Divisions, on beaches between San Jose and Dulag on the eastern coast of Leyte. [181] PLATE NO. 53 [182] The convoy, still loaded as for the Yap operation, left Hawaii on 15 September, resupplied at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands, and then proceeded to the Admiralties where some changes were made in the loading dispositions. The LST group left Manus Island on 11 October and the remainder of the convoy, consisting of the faster transports, departed on the 14th.31 Both X Corps and XXIV Corps were under the Sixth Army, commanded by General Krueger who had led the American ground combat echelons of the Southwest Pacific from New Britain to Morotai with unvarying sucess.32 Task Forces 78 and 79 were controlled by Admiral Kinkaid, Commander of the Allied Naval Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area and of the United States Seventh Fleet. In addition to responsibility for these two task forces, Admiral Kinkaid also had the over-all command of Task Force 77, the Central Attack Force. The battleships and cruisers of Task Force 77 were under Rear Adm. J. B. Oldendorf while the escort carriers were led by Rear Adm. T. L. Sprague. Many of these warships had seen long service and were borrowed for the occasion from units of the Central Pacific.33 Additional Fleet and Air Support The size and scope of the Leyte assault demanded the full utilization of all available resources in the Pacific Theater. Accordingly, Admiral Halsey's powerful Third Fleet was called upon to assist in the operation by providing tactical and strategic support and by protecting the forces involved in the amphibious landings. The Admiral's flag covered four great striking groups, each consisting of fast carriers, cruisers, destroyers and the newest American battleships. These ships were to cruise as far as the Ryukyus and Mindanao, striking heavy blows against Japanese installations, planes, and surface craft whenever the opportunity arose in order to weaken the enemy's expected counteractions. Since the Leyte landing beaches were beyond the range of land-based fighter protection, carriers of the Third Fleet were scheduled to be back in position before 20 October to support the assault phases of the operation and to cover the ground troops. Additional air support of [183] the landing and convoy cover was to be provided by escort carriers of the Seventh Fleet.34 This naval air strength was coordinated with General Kenney's Allied Air Force which was assigned a secondary role-the protection of the rear and the southern flank until airfields could be developed on Leyte. With the completion of new bases, General MacArthur's air umbrella would move forward once more to shelter his troops, but in the meantime the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces were to hit targets on Mindanao and in the Netherlands East Indies from their bases in New Guinea and Morotai. Working in close conjunction with the Thirteenth Air Force, the Royal Australian Air Force Command of the Allied Air Force, under Air Vice-Marshal William D. Bostock, was to protect the rear and assist in the preliminary neutralization of Japanese installations in the Netherlands East Indies. To further the offensive effort, search planes of the Allied Air Force were assigned to cover the eastern areas of the Indies, most of the Philippine Archipelago, and parts of the South China Sea in strikes against enemy air bases.35 The operations instructions detailing the responsibilities and missions of the forces involved were published on 21 September. They are characteristic of the GHQ orders that moved complex armies along an advance of thousands of miles. GENERAL HEADQUARTERS SOUTHWEST PACIFIC AREA A. P. O. 500 OPERATIONS INSTRUCTIONS 1. a. See current Intelligence Summaries and Annex No 3-Intelligence. b. Allied forces occupy the line : Marianas-Ulithi-Palau-Morotai and control the approaches to the southern and eastern Philippines. c. The Third Fleet, Admiral W. H. Halsey commanding, covers and supports the Leyte Gulf- Surigao Strait Operation by: (1) Containing or destroying the Japanese Fleet.

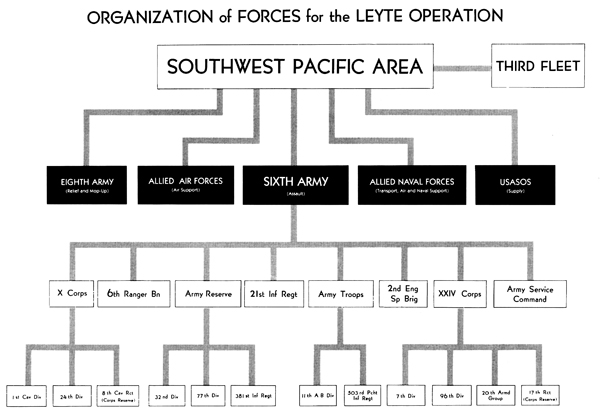

d. Coordination of operations of Third Fleet and Southwest Pacific Naval and Air Forces will be published later. e. I Time (Zone-9) or Z Time will be used during the operation. [184] PLATE NO. 54 [185] 2. a. Forces of the Southwest Pacific, covered and supported by the Third Fleet, will continue the offensive to reoccupy the Philippines by seizing and occupying objectives in the Leyte and western Samar areas, and will establish therein naval, air and logistic facilities for the support of subsequent operations. b. Target Date of A Day: 20October 1944. c. Forces.

3. a. The Sixth US Army, supported by the Allied Naval and Air Forces, will: (Plate No. 54) (1) By overwater operations seize and occupy

[186]

The Commanding General Eighth US Army, supported by the Allied Naval and Air Forces will:

c. The First Australian Army, supported by the Allied Naval and Air Forces, will continue: (1) The defense of naval and air installations within assigned areas of combat responsibility.

d. The Commander Allied Naval Forces, while continuing present missions, will:

[187]

e. The Commander Allied Air Forces, while continuing present missions, will: (1) Support the operation by

[188]

4 See Annex No 4-Logistics. (to be issued later) 5. a. See Annex No 5-Communications. b. Command Posts. Pacific Ocean Areas-Hawaii Third Fleet-Afloat General Headquarters, Southwest Pacific Area-Hollandia Rear Echelon-Brisbane

Sixth US Army-Leyte (as announced by Commanding General Sixth US Army)

First Australian Army-Lae Eighth US Army-Hollandia Allied Naval Forces-Hollandia Rear Echelon-Brisbane Allied Air Forces-Hollandia

United States Army Services of Supply-Hollandia

OFFICIAL:

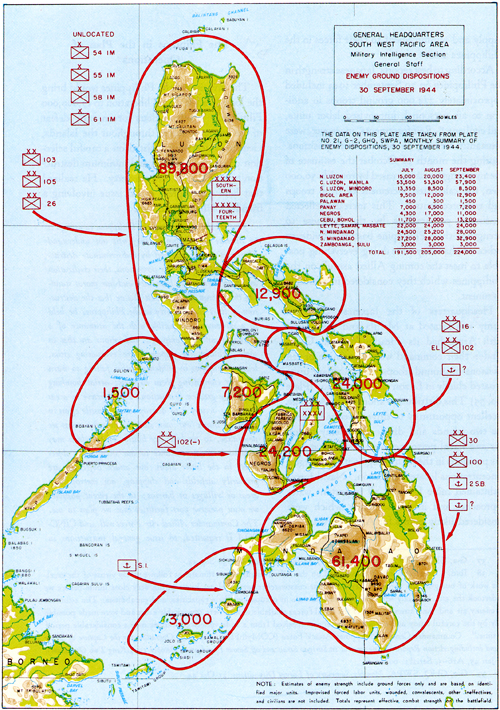

ANNEXES: (Omitted) The date for the invasion of the central Philippines had been advanced to strike the Japanese while their defense preparations were still generally incomplete. The original December target date would have given the enemy two more months to strengthen his positions and redeploy his forces.36 By seizing the opportunity to strike him at a disadvantage, however, the already considerable logistic problems inherent in operations conducted over great water distances were further complicated by the fact that the change in schedule came only thirty-four days prior to the new assault date. The cancellation of the landings on Mindanao which were originally intended to provide land-based air cover for the operation, altered the whole system of logistical support. These initially scheduled landings were to have been supplied from New Guinea bases. The Leyte operation, however, was partially supported directly from ports on the west coast of the United States. Coordination of the loading of supplies and equipment in two such distant areas necessitated the utmost care and timing. An added logistic difficulty was presented with the decision to employ the XXIV Corps in the Leyte operation. This corps was a Pacific Ocean Areas corps and, at the time, was actually aboard ship ready to sail for the operation against Yap which was cancelled. Shipping for the support of this Corps had been loaded to accord with the plans of the Pacific Ocean Areas, which did not fit well into the plans of the Southwest Pacific for the support of the Leyte operation. This shipping was in fact suited only for the specific support of the XXIV Corps, and it lacked the flexibility of standard loading, employed by the Southwest Pacific, which would have made it suitable to support any troops without regard to type or composition. Utilization of the XXIV Corps shipping during the critical phases of the operation was extremely difficult, and for a time its use was postponed in favor of the more flexible standard-loaded ships. Japanese Forces in the Philippines An examination of Japanese shipping routes and facilities for supply and reinforcement disclosed substantial transport traffic between Japan proper and the Philippines. While their shipping potential was considerably reduced from the level of the previous year, the Japanese were still in a position to give ready [190] supply and reinforcement to their forces in the Philippines area.37 According to best reports, Japanese strength in the Philippines on 30 September 1944 included approximately 224,000 ground troops in addition to air personnel, improvised labor units, and civilians.38 Reinforcements, moreover, were constantly arriving to bolster their positions. During the month of October the estimate of enemy strength was increased by roughly 50,000 men, the calculated increment of fresh troops and reinforcements.39 This increase reflected continued preparations by the Japanese to strengthen their Philippine bastion. Evidence indicated that they were doing everything possible to meet the coming Allied assault on the Philippines which they considered increasingly imminent. Headquarters of the Japanese Southern Army was located at Manila and the Thirty-Fifth Army had its Headquarters at Cebu. Under their command were some nine or ten divisions of ground troops, plus auxiliary units situated chiefly in Luzon and Mindanao. (Plate No. 55) This distribution afforded the Allies an excellent opportunity to drive a wedge between the two islands and divide the enemy forces. Air and naval personnel were scattered at various positions in the archipelago with the largest concentrations located in Luzon. Naval forces maintained mine fields at all important water approaches and inland sea areas which were considered likely points for Allied thrusts. The Filipinos in the Plan of Operations The invasion of the Philippines would bring the long-awaited day of liberation to 17,000,000 Filipinos. While anxious for an early defeat of the Japanese forces throughout the Islands, General MacArthur insisted on a careful selection of attack objectives and minimum destruction to Filipino life and property. He realized that here was a great moral issue involving a friendly civilian population:

[191] PLATE NO. 55 [192]

Aside from the matter of physical destruction of Filipino life and property, General MacArthur was well aware of the importance of restoring to the Philippines a degree of freedom at least equal to that in existence before 1942. In a letter to Maj. Gen. John Hilldring, Director of the Civil Affairs Division of the War Department, General MacArthur stated:

As the Leyte invasion date approached, the Allies increased the intensity of their air raids against important Japanese positions. Planes of the Far Eastern Air Force and the Third Fleet ranged over the western Pacific horn Borneo to the Bonins and continued to pound the enemy's ground and harbor installations. The Seventh Air Force, from freshly built bases on Peleliu Island, searched the Palau area and raided the Bicol Provinces of Luzon. The Fourteenth Air Force, based in China, joined in the all-out assault with intermittent blows against Hong Kong and Formosa, in diversionary operations. From 10-16 October, the U. S. Third Fleet launched its planes against Okinawa and Formosa in the greatest carrier strike of the war. The Japanese reacted violently to this intrusion into their inner perimeter and expended their planes on a lavish scale to counter the Allied attack. The resultant clash was one of the greatest air battles between carrier and landbased air power of the Pacific War. The Allied forces won a telling victory in the Formosan strike and inflicted great losses on the Japanese both in planes and in trained pilots.42 Without a pause, successive attacks were then directed against Luzon and the Visayas as the Allied invasion forces put the finishing touches on their amphibious preparations. In addition to the actual physical destruction inflicted on the Japanese in the Formosa attack, the Third Fleet's carrier raid had other important and far-reaching results. Formosa was an important arsenal for the supply and repair of the enemy air forces assigned to the protection of the Philippines, and the damage effected by the Allied strike seriously hampered the maintenance of subsequent air operations in Leyte and Luzon. Then, too, the approach of Admiral [193] Halsey's Third Fleet so close to Formosa led the Japanese High Command into a series of strategical errors.43 The prospect of finishing off a major portion of the U. S. task force was too inviting to resist. As a result, the Japanese diverted 150 and the last of the trained pilot strength of Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa's Third Fleet to accomplish this foredoomed mission.44 This attacking force was almost entirely destroyed, stripping the Japanese of any effective carrier plane power for use against the Allied landings in Leyte and influencing their defensive naval strategy in the Philippines. At this time, too, a naval task force under Adm. Kiyohide Shima was detached on the same futile task of destruction, additionally denuding Admiral Ozawa's fleet of cruiser and destroyer strength which it badly needed. This task force, instead of fulfilling its original mission as part of the Japanese Third Fleet's striking arm, was destined to play a lone and insignificant role in the forthcoming battle for Leyte Gulf. The subsequent enemy exaggerated damage reports caused the Japanese to reassess the probable date of the coming Allied invasion of the Philippines. Figuring that it was impossible for the Allies to replace their losses and repair the estimated damage to their fleet units before the end of November, the Japanese thought they had at least another month in which to strengthen their defensive measures in the Philippines.45 The " softening-up " operations were now finished and there remained only the final shore bombardment prior to the actual landing. Well over 1,000 enemy aircraft of all types had been destroyed by Allied air and naval forces during the preceding two weeks. Vast amounts of enemy shipping had been sunk or damaged. The enemy's most likely sources of reinforce- [194] ment for planes and men-Luzon, Formosa, and the Ryukyus-had been severely pounded. Whether Japanese communications had been sufficiently crippled to prevent an effective reinforcement of the troops on Leyte would soon be revealed. Guerrilla reports and other intelligence sources had given the Allies a good picture of what they would meet after their landing, but the enemy, on the other hand, had little precise information concerning Allied invasion plans. From the standpoint of strategy the Japanese calculated that the Allies would strike the Philippines soon after the Morotai and Palau landings. Tactically, however, they did not know precisely where, when, or in what strength the blow would fall. Estimates varied considerably both as to time and place. It was generally anticipated that the Allies would invade Mindanao first, then the central Philippines, and finally Luzon.46 The stage was set and the Allies were ready. In the Philippines, the people were eager to assist in the long-awaited battle for their liberation. After two and one half years of planning and fighting, General MacArthur could now fulfill his promise and reopen the gates of the Philippines to freedom.

[195]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||