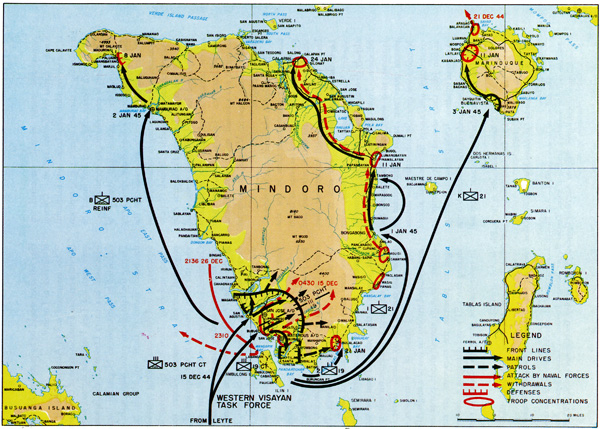

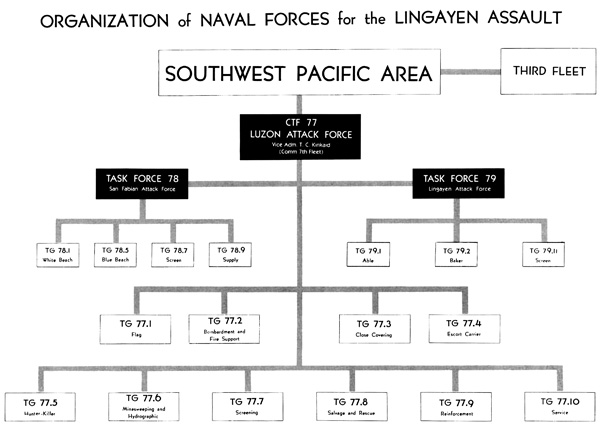

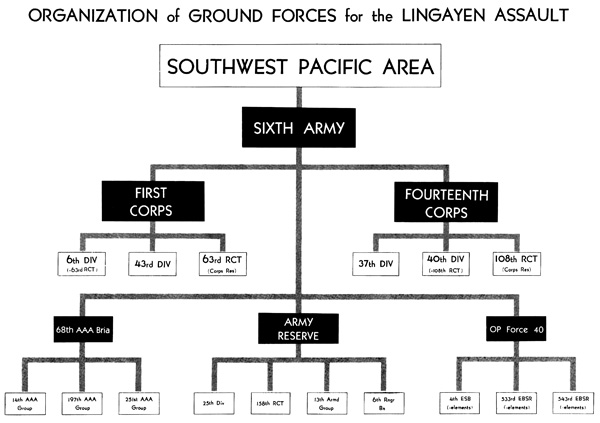

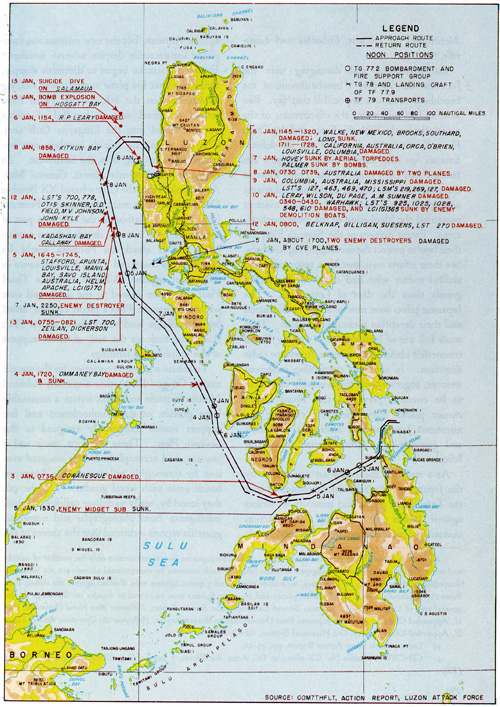

CHAPTER IX Plans for the Northern Philippines The curtain was raised on another stage of the Philippine theater while the concluding act of the Leyte operation was still in progress. This time the scene was set in Mindoro-the last steppingstone to the island of Luzon. The occupation of Mindoro as an immediate prelude to the main assault on Luzon was outlined in the final " Musketeer " plan of the Southwest Pacific Area. The sudden advancement of the date for the Leyte invasion had necessitated certain revisions in General MacArthur's original scheme of maneuver for the recapture of the Philippine Islands. To include the latest developments in the fast-changing picture, a third "Musketeer " plan was prepared on 26 September, covering operations to take place as soon as the seizure of Leyte was successfully accomplished.1 Under "Musketeer III," the first operation scheduled to follow the initial entry into the Philippines was the seizure of southwest Mindoro, contemplated for 5 December 1944. (Plate No. 67) The full-scale invasion of Luzon with landings along Lingayen Gulf was projected for 20 December, when it was expected that the airfields on Mindoro would be ready for use. Contingent provision was also made to support the Lingayen landing, if necessary, by an assault at Dingalan Bay on the east-central coast of Luzon. To provide for a fluctuating tactical situation, a preliminary attack at Aparri, in northern Luzon, was also tentatively outlined. This last operation, however, would take place only if carrier-borne aircraft could not insure uninterrupted transit of naval assault shipping around northern Luzon should such an alternate route be chosen. Concurrently with these operations, all other available Southwest Pacific forces were to undertake the consolidation of the Visayas, Mindanao, Palawan, and the Sulu Archipelago. It was planned that the Eighth Army would conduct these mop-up campaigns with such assistance as could be obtained from guerrilla units organized throughout the central and southern Philippines.2 Approval of " Musketeer III " by the joint Chiefs of Staff was dependent upon a final decision on the next major operation to be undertaken after Leyte. General MacArthur's plans called for an immediate invasion of Luzon as soon as success on Leyte was assured. Other ideas were being studied for by-passing Luzon and shifting the main effort of the Allies farther north.3 For some time, a direct attack on Formosa had been advocated to eliminate that island as an enemy assembly area and advance air transfer point. Allied occupation of Formosa would enable the utilization of its [242] airfields for heavy bombers to operate in conjunction with the newly acquired bases in the Marianas; at the same time the island would provide a staging area close to the heart of Japan. In addition, it was pointed out, Formosa could be used by the Allies to assist operations in China and prevent the consolidation of the Chinese coastal regions by the Japanese.4 General MacArthur did not believe that any operation should be undertaken against Formosa until the northern Philippines were firmly in Allied hands. Without Luzon, an invasion of Formosa would be logistically precarious in view of its great distance from the nearest available Allied bases, necessitating the movement of forces over extremely long and attenuated lines of supply.5 On the other hand, he felt that the Central Plain-Manila area on Luzon could be cleared of organized enemy units by February 1945 if the Lingayen landings were made on schedule, permitting operations north of the Philippines to be carried out earlier and with less risk than would otherwise be feasible since it was generally agreed that an assault against Formosa could not be prepared before February. Then, too, General MacArthur estimated that, with the obvious tactical and strategic advantages inherent in the establishment of extensive air and supply bases on Luzon, an invasion of Formosa would become unnecessary. Another major consideration in the choice of targets was the general shortage of service troops in the Pacific Theater. An invasion of Formosa would undoubtedly necessitate a large-scale transfer of service personnel from the Southwest Pacific Area. Already critically short for operations in progress, General MacArthur was unable to commit any service units from his command to an assault on Formosa. In this respect, he pointed out that the native population was an important factor in planning future operations. In Luzon, the Allies could depend upon thousands of loyal Filipinos to augment service troops by working as stevedores, engineers, carpenters, drivers, and in other fields of skilled and semi-skilled labor; the guerrillas, too, would undoubtedly play a large part in assisting a Luzon assault. In any event, General MacArthur contended, an invasion of Luzon as the next step in the Allied advance would be the most logical development in the strategy of Pacific operations since Formosa would not be a secure and satisfactory base so long as Luzon remained in enemy hands. On 3 October 1944, after careful examination of all the complex factors involved, the Joint Chiefs of Staff made their decision. In accordance with the general outline of SWPA's "Musketeer III" plan, General MacArthur was instructed to occupy Luzon with a target date of 20 December 1944. (Plate No. 68) He was also to establish bases on northern Luzon to support further Allied advances, including an assault by the Central Pacific forces against the Nansei Shoto (Ryukyu Islands), an operation set tentatively for 1 March 1945.6 Directives for possible operations against Formosa were withheld, pending further developments in the Philippine Campaign. As the Leyte operation progressed and the enemy's Kamikaze attacks became more damaging, some questions again arose as to the advisability of a direct approach from Leyte to Luzon. Naval commanders feared that an Allied convoy passing through the narrow, [243] PLATE NO. 67 [244] PLATE NO. 68 [245] restricted waters of the central Visayas would be subject to heavy air attack from the many enemy airfields in the surrounding islands. It was proposed that the alternate plan for the prior seizure of positions on Aparri be carried out to insure fighter cover for resupply ships which could then be routed around northern Luzon where more open seas permitted greater protection and safer passage.7 General MacArthur and his staff were in favor, however, of moving the Seventh Fleet and the necessary amphibious forces to Luzon along the southern route from Leyte via Mindoro. Although the danger of enemy air attacks would have to be faced during the initial invasion of Mindoro and the subsequent supply of forces located there, it was felt that once the new airfields were established, the Allies would have a much shorter route to Lingayen Gulf with greater air-protection and less exposure to the vicissitudes of typhoon weather than the suggested route around northern Luzon. In addition to these considerations, there was the added factor that an invasion of Aparri would delay the all-important Lingayen operation by at least a month.8 After a series of conferences between members of General MacArthur's and Admiral Nimitz's staffs early in November, it was generally agreed that the major amphibious forces would approach Lingayen Gulf through the Visayan waters while the powerful ships and carrier planes of the Third Fleet operated north of Luzon in cover and support missions; it was also decided that the Aparri operation need not be undertaken.9 Final Plans for the Mindoro Landing Even before the Sixth Army had left Hollandia for the Leyte assault, General Mac Arthur had issued instructions to General Krueger to prepare tentative field orders for the Mindoro invasion. Many of the details for the projected landings were worked out aboard ship, while the convoy was en route to the Leyte beaches. To conduct the ground operations on Mindoro, General Krueger constituted the Western Visayan Task Force, under the command of Brig. Gen. William C. Dunckel.10 The initial plan contemplated a landing on 5 December in a combined airborne and amphibious maneuver which would secure the San Jose area near the southwest coast in order to make [246] immediate use of its airstrips for the support of the Luzon operations11 and to counter the many Japanese airfields located on Luzon. (Plate No. 69) The delay in the development of Leyte airdromes and the continuing need for air support of the Leyte ground forces caused several changes in this original Mindoro plan. Fighters and bombers occupied all available space on the Leyte airstrips, and there was no room for the large transports which would have to carry the paratroops to Mindoro. Consequently, the airborne phase was cancelled and, instead, arrangements were made to transport the parachute regiment by water in LCI's.12 The status of airfield construction on Leyte also made it questionable whether land-based planes would be in position by 5 December to cover the dangerous interim period between the landings and the activation of new strips on Mindoro. The peculiarity of weather conditions in the Philippines further complicated the problem. Fifth Air Force planes based on Leyte were handicapped by the seasonal bad Weather common to the eastern Visayas, while flying conditions prevailing over enemy airfields in the Sulu Sea area were usually excellent. Hostile aircraft flying in from the west would thus be permitted to attack Allied convoys at Mindoro with little fear of counteraction by grounded Allied planes. After thoroughly considering the airfield construction problem, various naval recommendations, and the relatively low level of supplies on Leyte, General MacArthur decided to postpone the Mindoro operation for ten days to 15 December.13 The interlude was used to good advantage. While the Leyte airstrips were being developed and repaired, the Allied landings at Ormoc sped the Leyte operation to a successful culmination. In addition, the orders for the Mindoro assault were amended to include the seizure of the Calapan area on the northern coast and the occupation of Marinduque Island, to the northeast, to help foster an illusion that the next major Allied strike would be against the Batangas-Bicol region of Luzon. On r 2 December j944, the Western Visayan Task Force, escorted by warships of the Seventh Fleet, sailed from the Dulag area of Leyte and set a course for Mindoro via Surigao Strait. The voyage through the restricted waters of the Philippines was not without incident. The Japanese were quick to spot the convoy and, although most of their efforts were relatively minor, one strike was particularly damaging. In the early afternoon of 13 December, a single-engine Kamikaze plane, swooping in from the direction of Siquijor Island, skimmed swiftly across the glassy waters of the Mindanao Sea and crashed headlong into the super-structure of the Nashville, the flagship of the Task Force.14 Losses in the resultant explosions were heavy, with estimated casualties of 131 killed and 158 wounded. General Dunckel and several of his staff were hit by flying fragments and the Nashville itself was put out of action and forced to return to Leyte.15 As the amphibious forces sailed through the Sulu Sea, powerful groups of the Third Fleet threw a neutralizing blanket of carrier planes over Luzon from the east. Continuous air [247] PLATE NO. 69 [248] PLATE NO. 70 [249] patrols over enemy airfields prevented any sizeable sorties by Japanese aircraft. Control of the air corridors over Luzon was held until the evening of the 16th when a raging typhoon struck with devastating effect and forced the Third Fleet to postpone its air operation.16 Although the direction and timing of General MacArthur's next move after Leyte was, in general, correctly estimated by the Japanese, an actual landing in force on Mindoro was not considered probable. In early November, the staff of the Japanese Fourteenth Area Army judged that the U.S. Sixth Army would achieve tactical control over Leyte by the first part of December. General MacArthur's next assault, it was assumed, would be made somewhere in the western Visayas, probably on Panay or Negros.17 This conclusion was based upon the supposition that any amphibious force of the size needed to invade an island as large as Luzon would require air bases farther advanced and better situated with regard to weather than Leyte was able to provide. Air sites in the western Visayas, especially on Panay, were already developed and far superior to those on Mindoro. From the point of view of the Japanese, who were without bulldozers and pierced steel mat runways, the terrain of Mindoro was generally unfavorable for airbase construction and, except for the small airfield at San Jose, there seemed little to tempt an American invasion. It was presumed, therefore, that one of the islands in the western Visayas would be General MacArthur's next target and that Mindoro would be by-passed on his route of advance to Luzon.18 So unexpected was an American assault on Mindoro prior to a main invasion of Luzon that even when the Task Force was sighted in the Mindanao Sea on 13 December, the Japanese estimated its destination as Negros or Panay. During the 14th, enemy patrol planes searched the beach waters of these two islands, fully expecting to find American landing operations already under way. Even when the convoy had progressed beyond the western Visayas, there were still some elements in the Japanese High Command, especially in the naval and air forces, who held that a landing directly on Luzon was in the offing.19 Only when the American convoy was finally anchored off San Jose did the Japanese discover that Mindoro was the ultimate objective of the amphibious assault forces. On 15 December, after sailing past Negros and Panay with further interference from the enemy limited to weak raiding missions, the assault ships of the Western Visayan Task Force drew close to the beaches of southwest Mindoro. Following a short naval bombardment, troops of the 19th RCT and the 503rd Parachute Regiment went ashore without opposition and pushed rapidly inland. (Plate No. 70) The landing phase of the invasion was accomplished without the loss of a single Allied soldier, although several suicide planes managed to penetrate the transports' air cover, sinking two LST's and damaging a destroyer. In order that the convoy be exposed to enemy [250] air attack for as short a time as possible, some 1200 combat troops of the 77th Division had accompanied the assault forces, to be utilized at the beachhead for the sole purpose of unloading the necessary equipment. The innovation, improvised to overcome the shortage of service troops, was highly successful and all materiel was transferred to the beaches before nightfall. Their work completed, the 77th Division troops were then returned to Leyte with the emptied ships.20 By noon of the invasion day, the town of San Jose had been occupied and work was begun on its airstrips. Australian construction troops assisted in the conditioning of the airfields, two of which were already in use by 23 December. Mindoro was but lightly defended by the Japanese, and Sixth Army operations in the objective area consisted mainly of patrolling and light skirmishing. The main efforts of the Japanese to interfere with the Mindoro operation were confined primarily to actions by their air and naval forces. Allied resupply convoys ran a gantlet of determined and damaging Kamikaze attacks as they traversed the dangerous waters en route to the Mindoro beachhead. For a time the destruction wrought by these suicide assaults created a serious problem, especially with regard to aviation gasoline and air force technical supplies. Troops ashore were also subjected to sporadic and fatiguing night raids by hostile aircraft.21 During the evening of 26 December, a Japanese naval task force, consisting of 2 cruisers, 3 destroyers, and 3 destroyer-escorts, attempted an ambitious bombardment of Allied shore installations, but the enemy plan fell far short of its purpose. In its approach to the beachhead, the Japanese task force lost the destroyer Kiyoshimo to Allied air attack, and the damage suffered by the other ships limited the accuracy and power of its gunnery. The total effect of the bombardment was negligible and the damage was easily repaired. Several attempted torpedo strikes against ships at anchor were similarly abortive. This was the last time that major surface units of the Japanese Fleet interfered with Allied shore operations in the Philippines. The primary purpose of the seizure of Mindoro was to establish airfields from which land-based aircraft could bomb selected targets on Luzon and at the same time protect the assault and resupply shipping en route to Lingayen Gulf. Supplementing this aim was an extensive deception plan to obfuscate Japan's military leaders as they tried to anticipate General MacArthur's next target after Mindoro. This plan was twofold in intent. From a broad strategic viewpoint, it attempted by means of extensive naval operations in nearby waters to direct the enemy's attention to a possible Allied threat against Formosa and southern Japan. Tactically, it aimed to undertake such measures as would lead the enemy to believe that the main thrust of any Allied offensive on Luzon would be launched against western [251] Batangas or the Bicol Provinces. Ground operations in furtherance of this plan were directed by the Eighth Army which took over control of Mindoro from the Sixth Army on New Year's Day, 1945. As the first step in the tactical deception effort, one company of the 21st Infantry of the 24th Division moved on Bongabong along Mindoro's east coast on 1 January. Other troops of the same regiment then advanced by shore-to-shore movement to Calapan, the main town on northeastern Mindoro, while enemy-held villages on the northwestern side were also cleared. In all of these actions substantial assistance was rendered by organized guerrilla forces. Occupation of Marinduque Island, situated close to southern Luzon's Bicol Peninsula, was the next operation undertaken. On 3 January, a small force of the 21st Infantry landed unopposed at Buenavista, on the island's southwestern shore, and consolidated positions for the establishment of radar installations. Concurrently with these ground operations, additional steps were taken to conceal the Lingayen invasion plan from the Japanese. While United States bombers struck carefully selected targets on Luzon, other aircraft flew photographic and reconnaissance missions over the Batangas-Tayabas region and transport planes made dummy drops over the same area to simulate an airborne invasion. At the same time, Seventh Fleet motor torpedo boats patrolled the southern and southwestern coasts of Luzon as far north as Manila Bay from new bases on Mindoro, and mine sweepers cleared Balagan, Batangas, and Tayabas Bays. Landing ships and merchantmen also approached the beaches in these areas until they were fired upon by the enemy and then slipped away under cover of darkness. On instructions from GHQ, the guerrillas in lower Luzon intensified their activities and conducted ostentatious operations designed to divert Japanese attention to the south. Although it is not clear exactly to what extent these deception measures influenced the operational plans of the Japanese Fourteenth Area Army, it is certain that, in the period during and immediately after the Mindoro assault, the Japanese centered their attention on southwestern Luzon. To guard against the double threat of the Mindoro convoy either continuing on to Batangas or being the forerunner of a second strike destined for Luzon, additional forces were sent southward. On 14 December, the Japanese 71st Infantry was dispatched to Batangas and the 39th Infantry, reinforced, to Bataan. There is little doubt that, until General Yamashita began the actual deployment of his troops in accordance with his Luzon defense plan of 19 December, he remained greatly concerned over the possibility of an imminent invasion of the southern area of the island.22 In addition to providing an advanced base [252] PLATE NO. 71 [253] for airfields and for deceptive operations, the invasion of Mindoro broke the enemy's final link with the Visayas; his communication lines with the southern and central Philippines were completely disrupted, and any further efforts to move his troops from Luzon to the Leyte area were now utterly out of the question.23 The enemy was also compelled to make major changes in his transport routes between Japan and the southern areas. With the loss of Mindoro, Japan halted shipments of additional reinforcements to the Philippine Islands. Manila Bay was abandoned as a main stopping point for convoys moving to and from the Netherlands East Indies region, and all remaining shipping lanes were pushed toward the China coast.24 General MacArthur's campaigns in the Southwest Pacific Area now neared their climax. The battle for Luzon was at hand. In many respects the scheme of maneuver and organization of forces for the invasion of Luzon paralleled the plan of the Leyte operation.25 Naval forces were divided into three main sections with Admiral Kinkaid in over-all command. (Plate No. 71) The Bombardment and Fire Support Group and the Escort Carrier [254] PLATE NO. 72 [255] Group were under Admiral Oldendorf and Admiral Berkey, respectively; the San Fabian Attack Force under Admiral Barbey; and the Lingayen Attack Force under Admiral Wilkinson.26 The Third Fleet would again provide strategic support for the operation by neutralizing enemy airfields, and at the same time it would be prepared to give direct support whenever necessary. The Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces' land-based planes were to protect the flanks and rear by overwater searches and by strikes against enemy installations in the southern Philippines and the Netherlands East Indies. In addition, army aircraft were to give protection to convoys moving through central Philippine waters and, as far as possible, lend air support to ground operations. As at Leyte, the Sixth Army, under General Krueger, was to land two corps abreast, this time I and XIV Corps, containing the 6th, 37th, 40th, and 43rd Divisions in the assault phase, and the 25th Division, 158th Regimental Combat Team, 13th Armored Group, and 6th Ranger Battalion in reserve.27(Plate No. 72) The postponement of the Mindoro operation to 15 December caused a corresponding delay in the Lingayen Gulf landing, originally set for 20 December. A new target date, 9 January 1945, was chosen to give time for the reorganization of forces and for the establishment of airfields on Mindoro and also to take advantage of the favorable moon and tide conditions. The few extra days were used to replenish and repair fleet units, conduct landing rehearsals, and further co-ordinate plans for air and naval support. The Third Fleet struck its first blows in support of the Lingayen operation on 3 January 1945 in the Formosa and Nansei Shoto regions. Bad weather hampered most of the carrier strikes, but moderate successes were achieved against the enemy's airfields and harbor shipping. On 6 January, the Third Fleet moved back into position to begin its neutralization strikes against Japanese installations on Luzon, preparatory to the imminent Sixth Army landings. It was fairly certain that the Japanese would throw their remaining air power in the Philippines against General MacArthur's Luzon invasion forces, and it was also anticipated that the major portion of their air effort would consist of the suicide technique so effectively introduced at Leyte. Both these expectations were soon realized. The passage of the advance echelons of the bombardment and fire support units of the task force from Leyte to Lingayen Gulf was marked by persistent and damaging Kamikaze attacks. (Plate No. 73) One day after Admiral Oldendorf sailed forth on his voyage to Luzon, Japanese planes began to plummet down from the sky into his ships. On 4 January, the Ommaney Bay, an escort carrier, was damaged so badly that it had to be sunk. The following afternoon, the Louisville, Stafford, Manila Bay, Savo Island and HMAS Arunta and Australia suffered hits or damaging near misses. On 6 January, off Lingayen Gulf, the fire support groups were again attacked by the "largest and most deadly group of suicide planes encountered during the operation."28 At least sixteen vessels were struck during the course of the day resulting in extensive casualties both to ships and personnel. Admiral Oldendorf's flagship, California, received serious damage, as did the battleship New [256] PLATE NO. 73 [257] Mexico and the cruisers, Columbia and Louisville.29 So determined and damaging were the Japanese attacks that a bombardment of the beachhead areas was impossible that day. Bad weather had minimized the effectiveness of the air attacks by the Fifth Air Force and the Third Fleet, thrusting the brunt of the air defense mission on the escort carrier planes. An attempt had been made by the Third Fleet to maintain a continuous air patrol over all enemy airstrips during 6 January, but a solid overcast prevented the blanketing of the more northerly areas. Escort carriers of the Seventh Fleet did their best to protect the accompanying warships, but their efforts were met by a resourceful and skillful enemy who had improved his tactics greatly since the days of Leyte Gulf. The Japanese pilots were now relatively well trained and their deception measures excellent. They made full use of land masses, "window", and counterfeit identification devices to escape radar detection. In addition, continuing inclement weather, together with the relatively large area to be covered, prevented the Third Fleet's carrier planes from effectively covering the numerous Japanese-held airdromes on Luzon and grounded the army aircraft based on Mindoro. As a result of the heavy air opposition by the Japanese, Admiral Kinkaid requested that the Third Fleet repeat and intensify its strikes against Luzon on 7 January. This action necessitated cancellation of a planned sortie against Formosa, but the new mission was completed satisfactorily despite adverse weather.30 Enemy air attacks began to diminish sharply, indicating that his plane strength was nearing exhaustion; on the 8th, as the Third Fleet retired to refuel, only a handful of enemy aircraft sortied into the Lingayen Gulf area. The few remaining suicide bombers now appeared to be coming from the northwest. To eliminate this potential threat, General MacArthur asked that the China-based XX Bomber Command shift its main effort against Formosa from Keelung Harbor to the southern part of the island.31 It was also decided that a carrier-borne aircraft attack on Formosa would be preferable to continued Third Fleet presence in the Luzon region. Admiral Halsey's Third Fleet thereupon moved to the north and west while the Seventh Fleet's escort carriers, aided by all available land-based planes of the Fifth Air Force, took up the task of direct support of the amphibious landings. To insure adequate protection for the assault troops, General MacArthur requested Admiral Nimitz to retain in Luzon waters a reasonably large portion of the bombardment and fire support vessels temporarily assigned to the Seventh Fleet. These warships, on 7 and 8 January, had accomplished their assigned mission by thoroughly pulverizing the Lingayen beach areas with naval gunfire. On the 9th they stood by, ready to deliver call-fire. Initial intelligence from photographs and numerous guerrilla reports indicated that the shores of the [258] Gulf had been fortified by the Japanese.32 Enemy gun installations were found only on the eastern side of the Gulf, however, and a relatively small amount of counterbattery fire was required. Since the Japanese had withdrawn from the beach areas, an accurate assessment of the effectiveness and value of the naval gunfire was difficult to make. The work of mine sweepers, operating in close conjunction with the bombardment and fire support units, was highly successful. Few mines were found in the area and sweeping progressed well ahead of schedule, thus making the Gulf safe for shipping and amphibious craft. The assault convoys, meanwhile, proceeded through the Visayas and up the west coast of Luzon with only sporadic interference from the enemy. One notable attack took place on 5 January when the Boise, with General Mac Arthur aboard, became the target of two torpedoes from a Japanese midget submarine. Fortunately, both torpedoes were avoided by prompt and skillful maneuvering and the submarine was rammed and depth-charged immediately by a covering destroyer.33 In the early morning hours of 9 January all amphibious shipping arrived in Lingayen Gulf. Japanese suicide boats succeeded in sinking or damaging several of the LST's and LCI's but the landings proceeded smoothly. The entry plan for Task Forces 78 and 79, transporting I and XIV Corps, respectively, was so well co-ordinated that the four attack groups, one for each division participating in the assault, were in position off their designated beaches almost simultaneously along a front of twelve miles. I Corps under Maj. Gen. Innis P. Swift, consisting of the 6th and 43rd Divisions, landed on the left flank near San Fabian. XIV Corps, under Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold and made up of the 37th and 40th Divisions, went ashore on the right, in front of Lingayen and Dagupan towns. (Plate No. 74) The scheduled landing hour was 0930 and by 0940 all landing waves had hit the beach. Initial opposition on the beaches was limited to mortar fire from the hills in the San Fabian region which damaged some of the landing craft. By late afternoon, the four division commanders had assumed control ashore. The Luzon landing operation was announced in a communique of 10 January:

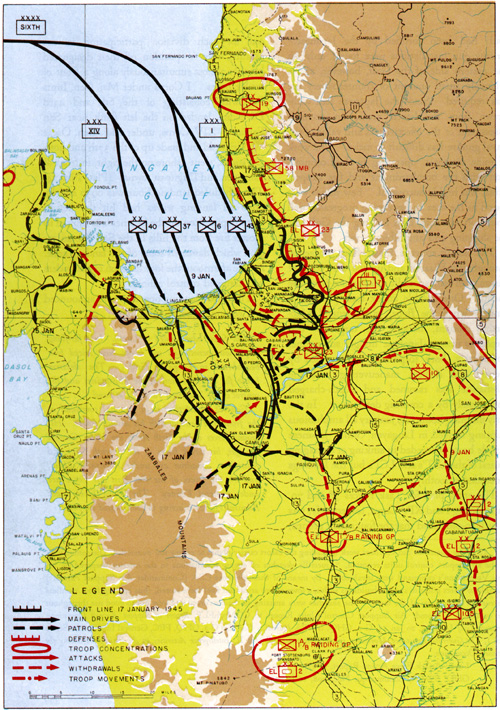

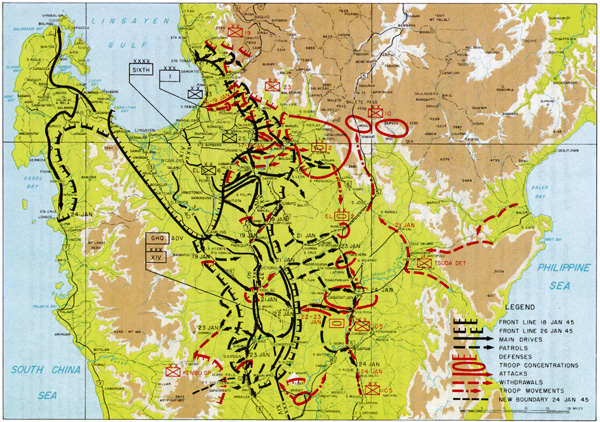

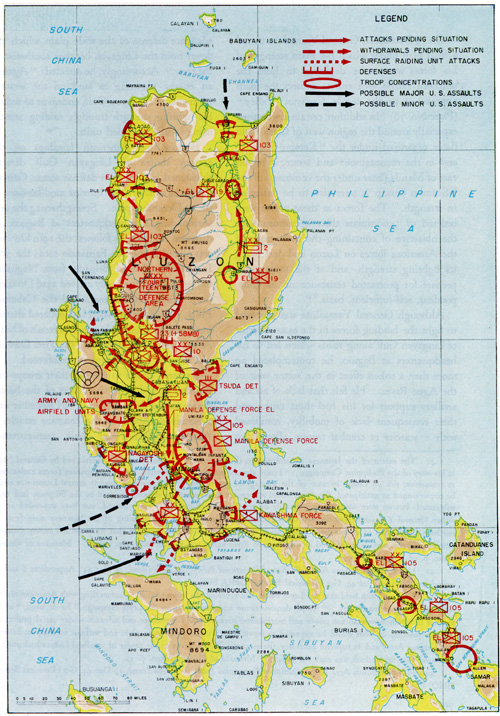

[259] PLATE NO. 74 [260] The strongest opposition to the initial inland progress of the Allied invasion force was met in the I Corps zone of action. As the five regimental combat teams35 moved into the mountains north and east of the San Fabian Damortis beachhead, they encountered a long arc of well-emplaced enemy positions covering all avenues of approach to Baguio and to the Cagayan Valley. This line of defense, built along a series of ridges beginning at Damortis, ran eastward and then southward through Rosario, Binalonan, and Urdaneta to anchor itself in the precipitous and rugged ground of the Cabaruan Hills. Again the Japanese had skillfully utilized the advantages of the terrain to protect the strategic passes and roadways with heavily fortified and mutually supporting cave and tunnel systems, fully supplied with all types of automatic weapons, mortars, and artillery. Most of these caves were self-sufficient strong holds containing enough materiel and food to withstand a protracted siege. Although artillery fire could be directed against positions located in the hillsides and ravines, it accomplished little toward neutralizing the powerful guns which were installed within the caves themselves. By the morning of 10 January, troops of the 43rd Division were in positions from San Jacinto to Rabon. After containing and then by-passing a strong concentration of Japanese entrenched in the Binday area, the division, reinforced on 11 January by the 158th Regimental Combat Team, began an arduous, stubbornly-resisted advance along the Damortis-Rosario road. The Japanese had done a thorough job of demolition to impede the progress of the American forces. Engineers were called upon to perform herculean tasks in the face of accurate enemy artillery fire, clearing the roads, removing cleverly constructed obstacles, throwing temporary bridges across streams, and, in one case, even ripping up twenty miles of railroad track to convert the roadbed into a motor highway. Rabon fell on the 12th; Damortis was entered on the 13th. By 16 January, troops of the 43rd Division and the 158th RCT had taken positions north and south of the Damortis-Rosario road near the Apangat River and continued to press against strong enemy defenses along the Rosario-Pozorrubio-Binalonan line. The 6th Division, on the right flank of the I Corps sector, was similarly slowed down in its move from the landing beaches. Strong enemy positions were met on the outskirts of the Cabaruan Hills, about twelve miles inland, southeast of the beachheads. The Japanese had established their principal defense point along a horseshoe-shaped promontory a short distance west of the Cabaruan barrio. All ridges to the west and northwest which covered the approaches to the main defenses were also well fortified and so cleverly camouflaged that even close-range scrutiny failed to reveal their location. In addition to the conventional pillboxes, dugouts, and interlocking trenches, ingeniously concealed sniper posts were strategically placed to protect the road nets to those positions. On 11 January, the 25th Division moved into the I Corps zone between the 43rd and 6th Divisions and instituted a drive in the area north and east of Urdaneta. On the 18th, elements of the 25th Division attacked heavy enemy forces at Binalonan, a key town on the network of roads leading to Baguio and the Cagayan Valley. From Binalonan, the division pushed northeastward to assault San Manuel. The town was strongly defended by the main force of the Japanese 7th Tank Regiment (the [261] Shigemi Detachment) and during the initial phase of the attack the advance of the American troops was slowed by heavy casualties. Artillery pieces and mortars fired down from the hills on the northwest of the town while all approaches were covered by enfilading and cross-fire of well-placed automatic weapons and antitank guns. Despite these formidable obstacles, the division forces moved stubbornly and steadily ahead and on 28 January, after repulsing a fierce tank counterattack in which most of the enemy's armor was destroyed, San Manuel was occupied and secured. Throughout the I Corps sector, the enemy plan of defense revealed itself as an attempt to command key terrain positions and control strategic points on the main highways. In many places, tanks and other armored equipment were discovered buried deep in the ground with their turrets protruding, for use as pillboxes in close support of infantry positions. Hard as such installations were to destroy, this unorthodox employment of tanks was not without benefit to the American forces, since the Japanese were forced to sacrifice many excellent opportunities for more logical and effective maneuver.36 By mid January, it was evident that the enemy was concentrated in strength in the sector guarding the roads to Baguio and to the Cagayan Valley and that any progress in that direction would necessitate intensive and sustained effort by the I Corps forces. On the right flank of the Allied invasion forces in the XIV Corps zone, the open terrain and paved highways of the Luzon Central Plain permitted a rapid advance southward on the road to Manila. General Krueger's strategy called for XIV Corps to drive southward through the Central Plain while I Corps protected the left flank by containing the enemy in the mountains to the northeast.37 The Central Plain, formed by alluvial deposits flowing from the high ranges bordering on the east and west, cuts a swath 30-50 miles wide through Luzon from Lingayen Gulf to Laguna de Bay-a distance of about 120 miles. A highly developed irrigation system, fed by numerous streams coursing down from the surrounding mountains, turns this vast region into an immensely fertile valley for the profitable cultivation of rice, sugar, and other staples. With its extensive plantations and well-developed transportation system of railroads and motor highways, Central Plain constitutes the wealthiest and most important area in the Philippines. XIV Corps' 37th and 40th Divisions, moving in parallel columns southward from Lingayen into the Central Plain, were virtually unopposed by the Japanese. The 40th Division moved along Highway No. 13 while the 37th Division, about eight miles on the left, moved down a second highway that runs from Lingayen to San Carlos and Bayambang. On 12 January, [262] the front line of XIV Corps ran from Bayambang on the east flank to Aguilar on the west. By 15 January, the Agno River had been crossed and still the Japanese had not been encountered in any sizeable force. Advance patrols of the 40th Division, instead of meeting enemy machine guns and mortars were greeted by joyous civilians who lined the roads and shouted encouragement.38 In fact, the very rapidity of the advance, coupled with the conspicuous failure of the Japanese to employ their usual tactics of defending key road positions, created a suspicion that some trap was in the making based on the hope that the Allied forces would overextend their lines. XIV Corps, therefore, kept a wary eye to the east, since its left flank was somewhat exposed when I Corps to the northeast was blocked in its drive by the heavy enemy defenses in the Cabaruan Hills. To safeguard this open flank, XIV Corps turned temporarily westward to seize Paniqui and Anao before continuing in its southward movement. With both these positions in Allied hands by 19 January, the advance to Manila was resumed. (Plate No. 75) On 21 January, the 40th Division occupied Tarlac without opposition while the 37th Division to the east held the line at Victoria. The advance of the 40th Division continued unabated until it reached the Bamban River. The Japanese had left a small garrison at this point to delay the capture of the airfield near Bamban and a brief but sharp skirmish ensued before the troops of the 40th Division were able to move ahead. As the forward drive continued southward from Bamban toward Fort Stotsenburg, the American forces began to encounter increasingly strong pockets of resistance which indicated that they were approaching the first outposts of the Japanese defense line. On 24 January, XIV Corps regrouped its two divisions and prepared for a co-ordinated advance in full strength. By 26 January, just 17 days from the date of landing, XIV Corps had advanced 59 miles to reach forward positions extending 124 miles, with 77 miles held by the 40th Division and 47 miles controlled by the 37th Division.39 The lack of enemy opposition to the 40th Division's advance west of the Agno River was not a trap but part of General Yamashita's general plan of defense. Forced to dispatch the cream of his original combat forces to the bitterly contested operation on Leyte, he no longer saw any possibility of winning decisive victories on Luzon. At first he had hoped that if additional replacements were sent from Japan, he could strengthen his thinly spread lines sufficiently to allow an aggressive and full-scale battle against the expected invasion forces. By the end of November, however, the decimation of the Japanese troops on Leyte and the tardy arrival of reinforcements from Japan convinced him that his only course of action was one which embodied a delaying defense to postpone the inevitable destruction of his forces as long as possible and gain time for the other Japanese forces north of Luzon.40 [263] PLATE NO. 75 [264] PLATE NO. 76 [265] On 19 December, General Yamashita issued a final plan under which the main strength of his forces was to be deployed to hold the northern Luzon area and to protect the main approaches to the fertile Cagayan Valley.41 (Plate No. 76) In addition, certain key sectors, especially around the region west of Clark Field (later organized under the "Kembu Group") and in the mountainous and strategic region east of Manila (later under the command of the "Shimbu Group "), were also to be defended in strength. The forces at these points were ordered to "coordinate their operations with the objective of containing the main body of the American forces on Luzon and destroying its fighting strength, and at the same time, prepare for protracted resistance on an independent, self-sufficient, basis."42 Although General Yamashita was prepared to fight the landing forces in the eastern sector of Lingayen Gulf along roads which led to his headquarters at Baguio, he contemplated no more than a token effort in the sector west of the Agno River. He felt that lack of air and artillery support for his fuel-short tanks and their consequent lack of mobility, combined with a scarcity of combat troops, allowed no adequate defense of the wide plain which ran down from the Lingayen beaches southwest of the river.43 Accordingly, he directed: "Against an enemy planning to land on the western peninsula of Lingayen Gulf, endeavor to reduce his fighting strength through raiding attacks using locally stationed units. ..."44 Because the American landings on the eastern shores of Lingayen Gulf directly threatened his northern defense sector, General Yamashita made a few hurried modifications in the 19 December plan. Strengthening the area surrounding his headquarters at Baguio, he disposed his forces as follows: the 19th Division was placed in the San Fernando area; the 58th Independent Mixed Brigade, from Naguilian to Rosario; and the newly arrived 23rd Division, from Rosario to Urdaneta and the Cabaruan Hills. This last division had suffered shattering losses en route to Luzon as a result of heavy Allied attacks. Supporting the 23rd Division was the 7th Tank Regiment, reinforced. Japanese efforts to transfer their troops into position according to the orders of the hastily drawn Luzon defense plan of 19 December were seriously disrupted by the constant attacks of American aircraft on their transportation [266] systems. In addition, the ceaseless harassing tactics of guerrilla units played havoc with their communication lines. As a result, General MacArthur's invasion of Luzon on 9 January gave these forces little and, in some cases, no time for the proper preparation of their assigned defenses. Many units were caught in the process of reorganizing or before their transfer movement could be completed. Contact between field troops and headquarters was poor, and some elements were cut off entirely as soon as the American troops began to push inland from their beachheads. While XIV Corps battled its way into the Clark Field-Fort Stotsenburg area, General MacArthur moved another force to the shores of Luzon. On 29 January, XI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Charles P. Hall and consisting of the 38th Division and the 34th RCT of the 24th Division, landed on the west coast of Zambales Province to push an additional wedge toward the Central Plain and Manila.45 This landing was also intended to prevent the enemy from attempting to duplicate General MacArthur's successful strategy of three years before in withdrawing into Bataan Peninsula for a prolonged and stubborn defense. The assault force, carried by the Seventh Fleet from Leyte through the Sulu Sea and Mindoro Strait, went ashore in the San Felipe-San Antonio area and began its advance inland.46 (Plate No. 77) Acting upon information furnished by guerrillas of the Zambales Military District, the pre-arranged naval bombardment had been cancelled although naval support remained to assist with call-fire if necessary.47 There was no opposition at the beaches and, after securing the airstrip at San Marcelino and occupying Grande Island at the entrance to Subic Bay, the main body of XI Corps pressed southeastward toward Castillejos and the town of Subic. Progress was unimpeded, and by the evening of the day of invasion both of these positions were in American hands. During the next morning, XI Corps moved into Olongapo, and by 5 February the vital passes to the Dinalupihan-Hermosa Road were denied to the enemy by flanking forces of the 38th Division and advance elements of the 40th Division. Any hostile movement to or from Bataan Peninsula was now blocked. [267] PLATE NO. 77 [268] XI Corps resumed its attack along Highway No. 7 but began to meet stubborn resistance as it approached well-entrenched Japanese forces and the rough terrain in the mountains of the Zigzag region. Zigzag Pass was strongly defended by mutually supporting, concealed caves and excellently camouflaged concrete emplacements. A deadly stream of machine gun and mortar fire poured out from these defenses, taking a heavy toll of the probing advance elements of the 34th RCT. After severe fighting and with the timely aid of several napalm bombing strikes by Fifth Air Force planes, Highway No. 7 was finally opened to traffic by 14 February. XI Corps continued to the south and east to secure Bataan Peninsula and also to assist in the opening of Manila Bay.48 Recapture of Clark Field an Fort Stotsenburg While XI Corps to the southwest was advancing across Zambales Province and I Corps was still hammering away at the tenacious and deeply entrenched Japanese forces in the hills and mountain ranges northeast of the Central Plain, XIV Corps prepared to attack the Clark Field-Fort Stotsenburg defenses. It was apparent from the strength and disposition of the opposing forces that the advance of XIV Corps to Manila would be materially affected by the evident enemy determination to make any capture of the airfield area as costly as possible.49 The question arose whether to contain the defended region with the 40th Division and move on to Manila with the 37th, or whether to launch a combined assault with the full strength of both divisions. There were numerous indications that the Japanese occupied the hills west of the main highway in considerable depth. Enemy counterattacks in force against the 4oth Division, if it were left unsupported, could conceivably cut eastward to cross the highway and interrupt the XIV Corps' line of supply to any forward units. The Corps commander, General Griswold, decided therefore to throw the entire weight of the Corps into a drive which would push the enemy forces westward into the hills and away from the highway.50 With the immediate areas of Clark Field and Fort Stotsenburg secure, the 37th Division could then resume the advance to Manila; the 40th Division, meanwhile, would push southwestward to pinch off the enemy by a juncture with XI Corps advancing northeastward along Highway No. 7. On the night of 27 January, while the 4oth Division inched slowly across the rugged ground of the Bambam Hills on the west, the 37th Division launched a combined tank and infantry attack against Clark Field and Fort Stotsenburg from the east. The 37th Division moved steadily into the objective area against heavy automatic and artillery fire, thickly-sown tank mines, and numerous enemy counterattacks. By 29 January, despite this fierce resistance, both Clark Field and Fort Stotsenburg had been captured and occupied by XIV Corps troops. The next day, in response to an invitation from General Griswold, General [269] Krueger officiated at the flag-raising ceremony. With Japanese artillery shells still falling on the western edge of the military reservation, the "Stars and Stripes" were flown once again over the post where, a little over three years before, General Wainwright had received the first startling news of the attack against Pearl Harbor.51 In their hasty retreat into the mountains, the Japanese were forced to abandon huge quantities of supplies to the advancing troops of the Sixth Army. A communique of 29 January reported:

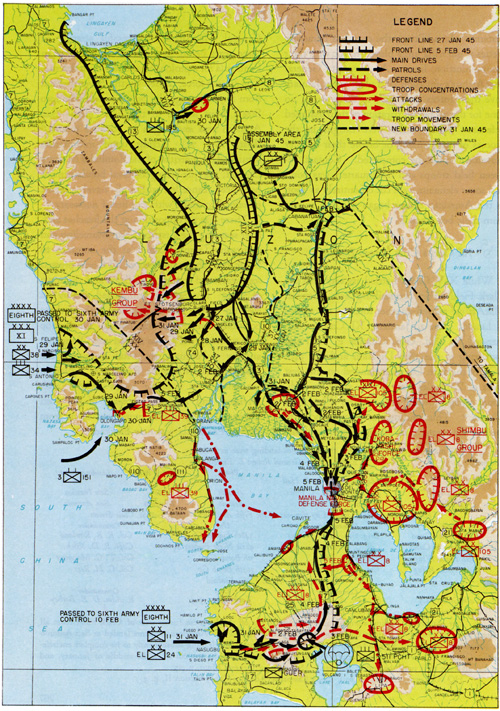

The 40th Division found it a difficult task to contain the enemy north and west of Fort Stotsenburg. The Japanese had chosen an ideal location from which to make their defense. The terrain in this region is characterized by steep ridges and isolated peaks interspersed with deep ravines and narrow, winding defiles which usually are the only paths of access to the main roads. Murderous machine gun and artillery fire from cave positions in the cliffs made any advance difficult and costly. At times the reduction of each cave individually was necessary before the American troops could move on to their next position. By the beginning of February, the advance elements of the 40th Division, XIV Corps, and the 38th Division, XI Corps, were in contact at Dinalupihan on Highway No. 7. The 37th Division, after securing the Fort Stotsenburg area was reforming in preparation for the drive to Manila. To the north, I Corps was moving slowly eastward. The 43rd Division had captured Pozorrubio on 18 January and pushed on against stiff resistance through Pimmilapil and Concepcion to improve its position on the Damortis-Rosario road. The 25th Division, battling courageously against a stubborn enemy southwest of Asingan, progressed toward Baligayan. On the right flank of I Corps, the 6th Division had driven through the Cabaruan Hills to occupy Urdaneta, and advance forces of the division were pressing southwest toward Talevera and Munoz. The final drive to Manila was initiated by General Krueger's Field Order No. 46 issued on 30 January 1945. This order fixed the boundary between XIV Corps and I Corps, putting the towns of Dagupan, San Carlos, Malasiqui, Carmen, and Victoria within the XIV Corps zone and the positions from Licab to Cabu and Tamala, in the I Corps zone. The line of demarcation on the southwest, between XIV Corps and XI Corps, ran from Purac on the west coast through Dinalupihan and Orani. The 1st Cavalry Division, which had landed on Luzon on 27 January, was attached to XIV Corps four days later with orders to approach Manila on the left flank of the 37th Division by initiating an advance across the Pampanga River to secure the line from Hagonoy through Sibul Springs and Cabanatuan.53 In the early morning hours of 11 February, the 1st Cavalry Division under Brig. Gen. Verne D. Mudge, moved out of its assembly area at Guimba and began an advance southward. The Pampanga River was quickly crossed, [270] and by evening advance elements of the division had penetrated as far as Cabanatuan.54 Here two squadrons of Brig. Gen. John H. Stadler's 1st Cavalry Brigade formed a "flying column" in conjunction with the 94th Tank Battalion and moved in swiftly to surprise the Cabanatuan defenders. The Japanese had placed a 3000-pound charge of dynamite to destroy the bridge across the Pampanga River and planned to detonate the explosives with mortar fire before the American troops could effect a crossing. Quick action by General Mudge in leading his men onto the bridge to throw the dynamite into the river even though the mortar shells had already begun to fall, foiled the enemy plan, preserved the bridge intact, and enabled the cavalrymen to proceed with little difficulty. Once the bridge was crossed, further progress was relatively unopposed as forward elements of the 1st Cavalry Division raced down Highway No. 5 to contact units of the 37th Division at Plaridel near the Angat River. The movement of the 37th Division along Highway No. 3 was greatly impeded by the thorough demolition work of the retreating Japanese as a result of which almost every important bridge along the route of advance had been destroyed. On 2 February, elements of the division passed through Calumpit and Malolos while other units engaged an enemy road block just north of Plaridel close by the Angat River where first contact was made with the cavalry patrols. After a bitter all-night battle, Plaridel and the river crossing were secured. The 1st Cavalry Division meanwhile forded this river at a point to the east and then continued on rapidly toward Novaliches. By evening, XIV Corps, fulfilling its assigned task, held the line from Hagonoy through Sibul Springs to Cabanatuan.55 General Krueger's strategy for retaking Manila involved an assault on the capital from two directions. The 1st Cavalry and 37th Divisions of XIV Corps would launch the main attack from the north, while a smaller but nonetheless strong effort would be carried out on the south by combined airborne and infantry forces.56 On 31 January, the Eighth Army landed troops of the 11th Airborne and 24th Divisions on Batangas Province to form the lower jaw of the Manila pincer movement. The 11th Airborne Division, less the 511th Parachute Infantry but reinforced by two battalions of the 24th Division, landed by water to establish a virtually uncontested beachhead at Nasugbu, a little over 30 miles southwest of Cavite.57 The suicide thrusts of small enemy [271] torpedo boats attempting to attack the landing craft were promptly and easily crushed. General MacArthur described the tactical implications of this landing as follows:

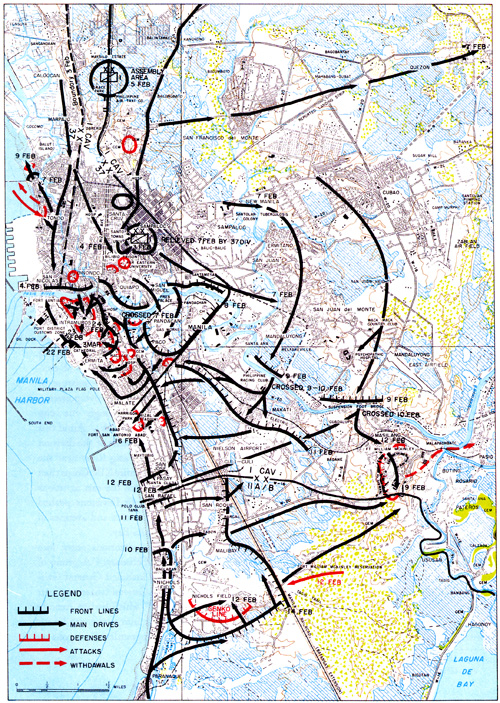

On 3 February, the remaining parachute regiment dropped on Tagaytay Ridge on the north shore of Lake Taal. A juncture of the two forces was quickly effected and the combined paratroop units moved northward along Highway No. 17 toward Manila. Opposition was slight and the troops drove rapidly ahead until they reached the permanent concrete and steel emplacements which guarded Nichols Field. Here the division halted to consolidate until heavy artillery could be brought in from XIV Corps.59 Both the northern and southern outskirts of Manila were now reached, but the relative ease of movement which had hitherto characterized the American advance down the Central Plain was by no means an indication of the nature of subsequent progress. Although General Yamashita had begun to evacuate the bulk of his forces and supplies from the Manila area in mid-December while the Allies were carrying out their invasion of Mindoro, American intelligence estimates listed between 15,000 and 18,000 enemy troops still remaining intrenched within the city.60 These troops, consisting mostly of naval base units, were intended not only to protect the removal of the rest of the vast quantities of supplies and equipment which had been stored in the capital, but also to deny the use of Manila's harbor facilities, airfields, and other important installations for as long a period as possible.61 Although the defenses inside the city were generally improvised and adapted to meet a rapidly shifting tactical situation, the tenacity and bitterness of the resistance encountered made the American seizure of central Manila an exhaustive and prolonged effort. As the forward elements of the 1st Cavalry Division advanced from the Angat River, word was brought that some 4,000 American and other Allied prisoners were interned at Santo Tomas University and that others might possibly be held at Malacanan Palace. The same "flying column" that had so effectively spearheaded the drive into Cabanatuan was immediately dispatched to free these internees lest they be harmed while the battle for Manila was in progress.62 At dawn on 3 February, the cavalrymen left Santa Maria and sped swiftly southward. The bridge at Novaliches [272] over the Tuliahan River was reached just in time to extinguish the still burning fuses of an enemy demolition charge. After the bridge was crossed, numerous small groups of Japanese in ambush along the road tried to delay the advancing troops with small arms fire. When the cavalrymen entered the northern suburbs of Manila, the hangars and airfield equipment at Grace Park were already ablaze and little could be saved. The "flying column" proceeded down Rizal Avenue to Santo Tomas University, meanwhile diverting one troop of cavalry and a platoon of tanks to Malacanan Palace. Resistance on the University grounds was stiff but, with tank support, the Americans forced the main gates and wiped out the enemy troops in the area. All internees were liberated with the exception of 221 who were held as temporary hostages and released the following morning.63 Malacanan Palace was also reached against sporadic rifle fire from across the Pasig River but only Filipino police guards and attendants were found to occupy the building. The bulk of the remaining cavalry units was assembled in the vicinity of Novaliches by 3 February. Further progress was temporarily interrupted while repairs were made on the bridge which the enemy had finally managed to destroy after the "flying column" had passed. The advance was soon resumed, however, and by 5 February, the cavalry troops had begun to gather in the Grace Park area. (Plate No. 78) After its brief contact with patrols of the 1st Cavalry Division at the Angat River, the 37th Division pushed along Highway No. 3 against constant automatic and mortar fire. The Japanese had blown the bridges at every stream crossing and progress was relatively slow. Malanday and Caloocan were occupied on 4 February, and Manila was entered on the same day. The division effected its own rescue mission when some of its units entered Bilibid prison and discovered 800 American prisoners of war who had been abandoned by their jailers. The brilliant record of the Sixth Army in the release of prisoners of war and internees on Luzon was described in a communique of 6 February:

As the 37th Division approached the Pasig River, it was met by a devastating enemy machine gun and rifle barrage. Incessant detonations and collapsing structures filled the air with deafening concussions. The entire sky was lighted with the roaring fires of conflagrant buildings and at times the mixture of smoke, heat, and dust became so overpowering that substantial progress through the city became an almost impossible task. Amid this holocaust and bedlam, elements of the division effected a crossing of the Pasig River near the Presidential Palace. The entire XIV Corps then began an envelopment from the east as troops of the 1st Cavalry and 37th Divisions pushed laboriously through the streets and avenues of the capital toward Manila Bay. General MacArthur's victorious entry into Manila was made on 7 February. A group of officers and men which included General Griswold, General Mudge, General Chase, and part of the " flying column " which had so recently distinguished itself, met him at the city limits. General MacArthur congratulated everyone on [273] PLATE NO. 78 [274] a job well done and then drove through the war-torn Philippine capital amidst the acclaim of a grateful populace. Sniping and artillery fire continued in almost every section of the city as he visited the Malacanan Palace and the front-line troops engaging the enemy along the Pasig River.65 On 10 February, control of the 11th Airborne Division, drawn up south of Manila, passed from the Eighth Army to the Sixth Army.66 On the same day, XIV Corps artillery poured a steady concentration from the north into the enemy concrete installations on Nichols Field, placing the shells with deadly accuracy in front of the forward paratroop positions. Under cover of this barrage the airborne division moved its tanks against the thick pillboxes. General Swing's plan was to circle northward and move on the west flank of the Japanese defense line. By the end of the day, the paratroops had seized positions to within r000 yards of the Polo Club-the main core of enemy resistance northwest of the airfield. Thus, in the first week of February, General MacArthur had three divisions inside Manila the 37th Division, attacking south across the Pasig River and on toward the Intramuros area; the 1st Cavalry Division, moving south-westward across San Juan Heights toward Neilson Field; and the 11th Airborne Division, pressing north and east across Nichols Field toward Fort McKinley. Despite this sizeable force, the occupation and clearing of Manila was an arduous task. The Japanese troops in the city fought bitterly, knowing that their chances of escape were small. Improvised positions were set up behind piles of fallen debris, barricaded windows, and sand-bagged doorways. Every vantage point was manned and fiercely defended with a solid curtain of machine gun and rifle fire. The heaviest fighting took place in the sector assigned to the 37th Division. The Japanese in this area struck out viciously from every position, fighting from building to building and from room to room without surrender. It was not until 17 February that the division was able to launch its assault on the Intramuros, the venerable XVI century citadel in western Manila near the mouth of the Pasig River. Even by modern standards this ancient "Walled City" was a formidable fortress, ringed with a stone wall 15 feet high and widening from 8 to 20 feet at the top to 20 to 40 feet at the base. Four of the main gates were covered by mutually protecting redoubts backed by a heavily fortified concrete building. Complicating the problem of breaching this massive bastion was the fact that many non-belligerents, mostly women and children, were within the city. Because of these helplessly imprisoned civilians, all thought of pulverization of the Intramuros area by air bombardment had to be abandoned. A plea was broadcast to the Japanese entrenched within, either to surrender or at least to evacuate the civilian population and prevent unnecessary bloodshed. No answer was received. There was no choice but to order a time-consuming infantry assault to move in, after the way had been prepared by artillery and mortars. The attack started with 105 mm and 155 mm howitzer shells blasting huge chunks out of the ancient walls. On the 19th, under cover of a heavy smokescreen, 37th Division troops began to pour through the breaches and over the rubble to meet the waiting Japanese. The enemy positions in the immediate vicinity of [275] the walls had been effectively destroyed by the terrific power of the preliminary bombardment, and the initial incursions of the American forces met with comparatively light losses. Resistance mounted swiftly, however, as the troops advanced. To add to the difficulty, movement became greatly impeded by the streams of refugees that swarmed out of the buildings and milled around the streets. Fire had to be withheld until these scattered masses of civilians could be removed from the battle zone. By 24 February, after a week of savage fighting characterized by numerous hand-to-hand engagements and room-to-room combat, the entire Intramuros was in Allied hands. On 28 February General MacArthur made the following address upon reestablishing the Commonwealth Government in the city of Manila:

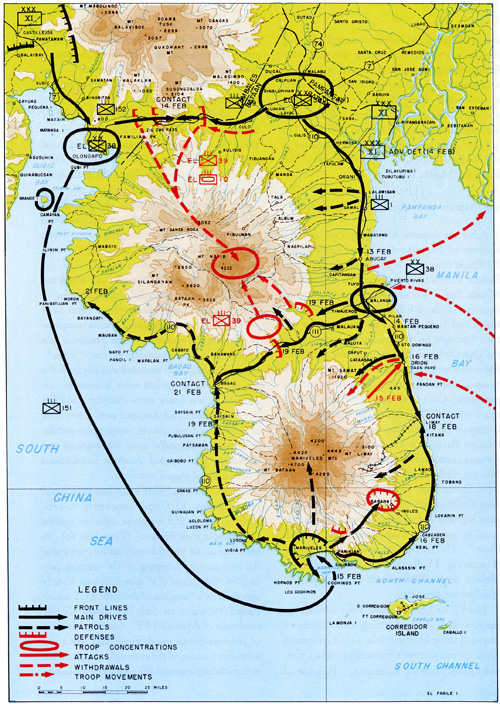

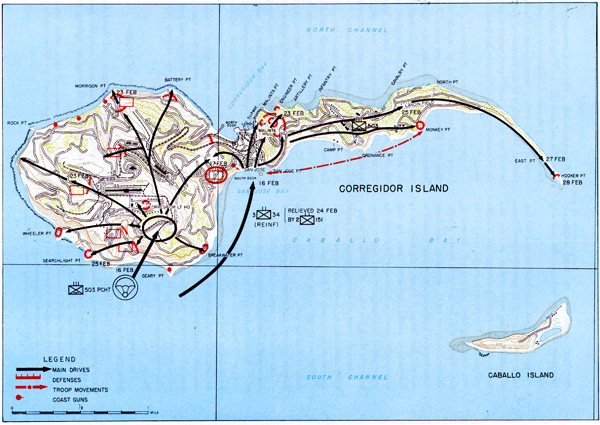

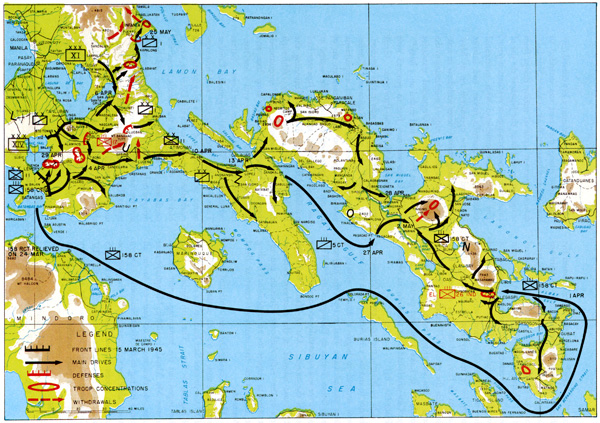

On 9 and 10 February, units of the 1st Cavalry Division crossed the Pasig River and fanned out in three directions-toward Manila Bay on the west, Neilson Field on the south, and Fort McKinley on the southeast. Elements of the 11th Airborne Division, meanwhile, swept the enemy from Nichols Field by the 13th and moved on to Neilson Field and Fort McKinley.68 Rather than be caught between the two advancing forces, the Japanese aban- [276] doned Neilson Field without a struggle. During the last two weeks of February, the enemy defenses throughout the city were reduced to widely scattered and rapidly shrinking pockets of opposition. Rizal Stadium, Fort McKinley, and the buildings along the harbor district were occupied after short but intense fighting. On 3 March, the last organized enemy defenses in the Welfare Park area were overcome. The battle for Manila was over. After the capture of Zigzag Pass and the opening of Highway No. 7 on 14 February, XI Corps continued on its mission to occupy Bataan Peninsula and clear the entrance to Manila Bay. To strengthen the Corps, one regiment of the 6th Division, the 1st Infantry which had been relieved at Urdaneta by the 25th Division on 18 January, was attached to the 38th Division. For the recapture of Bataan, two forces were designated to carry out simultaneous operations along both sides of the peninsula. On 15 February, a "South Force" of the 151st RCT, 38th Division, sailed from Olongapo on Subic Bay and landed at Mariveles on Bataan's south coast to take up the advance northward along Highway 110. (Plate No. 79) Meanwhile an "East Force" of the 1st Infantry, 6th Division, moved overland from Dinalupihan on the northern end of this same highway and advanced down Bataan's east coast to establish contact with the "South Force". The 1st Infantry also had the mission of securing Highway No. III which runs laterally across Bataan from Pilar on the east to Bagac on the west. The "East Force" seized Pilar without opposition and, after , diverting two battalions westward along Highway No. 111, it continued south against scattered resistance to take Orion and Limay in quick succession. Progress of the "South Force" was delayed only by a group of fortified enemy pillboxes in the mountains immediately northeast of Mariveles. This obstacle was quickly eliminated, however, and the advance was resumed. By 18 February, both forces had joined at Limay to occupy the entire length of highway along the east coast of Bataan. A co-ordinated attack by 38th Division forces, assisted by Fifth Air Force planes, dislodged the stubbornly resisting groups of Japanese infantry who were deeply entrenched near Bagac along Highway No. III. By 21 February, the 38th Division had secured all objectives on the peninsula. Thus, within the short space of seven days, Bataan was once more in American hands. Just as in the dark days of 1942 when the fall of Bataan had preceded the capitulation of Corregidor, so now, almost three years later with the roles of the opposing armies completely reversed, the recapture of the peninsula was a prelude to the recovery of the "Rock". Corregidor had been pounded steadily from the sea and air since the last week in January. In addition to the heavy naval shelling, the Fifth Air Force alone had dropped over 3,000 tons of bombs and napalm in some 2,000 sorties, shattering the island's outer fortifications and crumbling the exposed concrete installations into a mass of jagged rubble. On 16 February, after a last powerful naval bombardment, XI Corps launched a co-ordinated airborne and seaborne invasion against the strategic rock fortress. (Plate No. 80) A battalion of the 503rd Parachute Infantry made the first assault, dropping on the western portion of the island; it was followed shortly afterward by a battalion of the 34th RCT which landed by water on San Jose beach slightly southwest of Malinta Hill. Another battalion of airborne troops was dropped later that afternoon but because of the extremely rough terrain in the landing area and the increasing casualties [277] PLATE NO. 79 [278] PLATE NO. 80 [279] from heavy enemy fire, the third battalion of paratroops came in by water on the following day. The 503rd Parachute Infantry and the battalion of the 34th RCT quickly joined forces to eliminate the main system of cave and tunnel defenses running through the Malinta Hill district. The Japanese fought to the bitter end, defending each position with devastating fire. Rather than be dislodged by the irresistible onslaught of tanks, bazookas, and flame throwers, they blew up many of their tunnels in suicidal desperation. During the night of 23 February, a terrific explosion from the vast ammunition stores in Malinta Hill shook the entire island of Corregidor and sent its reverberations along the whole of Manila Harbor. Although these self-sealing tactics did cause many casualties to American troops caught in the immediate vicinity of the blasts, the over-all effect was to lighten the task of cleaning out each individual cave. By 27 February, the American forces had seized complete control of all commanding ground on the island, and on the next day Corregidor was pronounced secured. The twelve-day fight had been vicious and bloody. Virtually the entire Japanese force of 4,700 troops had been annihilated with only a handful taken as prisoners-somber and undeniable attestation to the tenacity of the enemy's resistance. Another chapter had been added to the long story of bitter battles that characterized the campaigns in the Southwest Pacific Area. The capture of Corregidor by United States forces marked a historic milestone in the war against Japan. The "Rock", after a hard and bitter three-year campaign which carried General MacArthur to Australia and back, was again in American hands. For the Commander-in-Chief this was more than a victory in arms over the enemy; it was the fulfillment of a personal crusade. In a stirring ceremony on 2 March, General MacArthur, in the presence of members of his pre-war staff,69 gave orders to raise the colors once more over the tiny, battle-scarred island.70 In the meantime the area of operation of XI Corps had been expanded to include the enemy's "Kembu" defense sector west of Fort Stotsenburg. On 21 February, the Corps assumed the responsibility for the direction of the 40th Division which had been engaged in the lone and difficult task of clearing large concentrations of well-equipped and tough Japanese troops from their strongly prepared hill positions in the Zambales Mountains. On 26 February, the exhausted troops of the 40th Division were replaced by the 43rd Division which, in turn, was relieved of its mission in the I Corps zone by the newly arrived 33rd Division. The 43rd Division was ordered to launch a co-ordinated frontal and enveloping attack to eliminate the main centers of resistance in the Zambales area. Substantial advances were made on all fronts and, on 7 March, the 43rd Division was again withdrawn, this time for action in the region east of Manila, while the 38th Division moved up from Bataan to continue the attack in Zambales and complete the detailed mopping-up of both provinces. Manila had fallen, Bataan and Zambales Provinces were occupied, and Corregidor had been recaptured, but the toughest fighting of [280] the Luzon campaign was still in the future. In consonance with his general plan of a protracted defense of the island, General Yamashita had grouped his forces in strategic positions to protect the approaches to the Cagayan valley and the mountain fastness of northern Luzon. There was still much action ahead for XIV Corps in the Batangas and Bicol regions but the "Yamashita Line," extending from Anti polo on the south through the hills around Montalban and Ipo Dams on to Cabanatuan and then into the northern mountains, was to prove the greatest obstacle to the battling forces of the Sixth Army. The portion of the "Yamashita Line" that ran east of Manila from Antipolo through Montalban to Ipo Dam was known as the "Shimbu Line" and was defended by a heterogeneous collection of Japanese combat and service units numbering approximately 30,000 troops. These troops were distributed among three enemy forces protecting the main positions east and northeast of Manila: the Kawashima Force in the northern Ipo sector, the Kobayashi Force in the central Marikina sector, and the Noguchi Force in the Antipolo sector to the south. In addition there were about 13,000 miscellaneous troops scattered through the rear areas and some 9,000 troops which had withdrawn from Manila during the first stages of the battle for the city. These Manila escapees comprised mostly naval units and took little part in the fighting, filtering through the lines toward Infanta and then melting into the mountains along eastern Luzon.71 The "Shimbu Line" presented a triple threat to XIV Corps since, potentially, the enemy could launch a counterattack against the extended left flank of the Corps or, by controlling the vital dams, dominate or destroy the water supply to Manila or, with long range artillery, lob shells into the capital itself. The 6th Division, transferred from I Corps to XIV Corps on 17 February, pressed against the central and northern sectors of the enemy's line of defense while the 1st Cavalry Division and later the 43rd Division moved against the Antipolo region. (Plate No. 81) On 5 March,72 after the fall of Manila, XIV Corps ordered a combined assault by the 1st Cavalry and 6th Divisions to cut between the Wawa and Antipolo areas and effect an envelopment from the south of the enemy's strong points on Mt. Mataba and Mt. Pacawagan. On 8 March, after a heavy two-day plane bombardment of enemy positions north of Antipolo, XIV Corps began the offensive to the east. Resistance was fierce and progress slow, but by 14 March considerable advances had been made. It was on this date that Maj. Gen. Edwin D. Patrick, commander of the 6th Division, was fatally struck by a sudden burst of enemy machine gun fire which raked his advance observation position.73 The formidable cave defenses in the Antipolo-Wawa line were well described in a GHQ communique:

[281] PLATE NO. 81 [282]