CHAPTER VII

Staffs for Germany

Although the COSSAC approach rejected the idea of national military government headquarters separate from the combat commands, the COSSAC planners themselves, before they were finished, found that they could not be entirely consistent in applying the Standard Policy and Procedure to Germany. The Moscow and Tehran Conferences had made the Allied administration of Germany after the war a certainty. Furthermore, of the three phases Colonel Troubridge identified in his report known as Slash 100, the second phase, coming between the end of hostilities and the assumption of control by an Allied commission, entailed a period of central administration by SHAEF in the western zones. How long the period would last could not be determined exactly, but the first SHAEF estimate, according to Troubridge, was six months. Consequently, the Supreme Commander would have to be prepared to conduct military government in Germany through the normal military command channels specified in the Standard Policy and Procedure until the fighting stopped, and through military government technical channels for some time thereafter.1 In his first proposal concerning the SHAEF civil affairs organization, Lumley included a German country unit which would prepare plans and eventually form the agency through which the Supreme Commander would control the British and American zones until the control commission took over.2

The SHAEF reorganization of February 1944, however, influenced by the AMGOT philosophy, disregarded the COSSAC separation of the two phases of military government and gave the German Country Unit responsibility for exercising control in Germany "from the time Allied military forces enter Germany until such control passes to an Allied High Commission," that is, during both the first and the second phases.3 Under the reorganization, the German Country Unit moved into the Special Staff under the DCCAO, McSherry, and on 16 February, Col. C. E. D. Bridge (British ) and Colonel Troubridge, assisted later by one other British officer and three U.S. officers, Lt. Col. Bernard Bernstein and Majors Galen Snow and L. J. Chawner, began laying out the missions and structure of the unit.4 They identified its tasks as being to plan for and later constitute the main military government headquarters for Germany, to write a handbook which would be a comprehensive military govern-

[80]

ment manual for Germany, and to provide advice and direction to the military commands and to the other civil affairs echelons. Lumley, trying to prevent the unit and its ambitions from expanding too rapidly, proposed limiting it at first to a 20- or 30-officer complement. The planning committee rejected his idea, however, and set the minimum initial strength at 102 officers with an anticipated progressive expansion of 400 to 600 officers.5 At conferences in late February, General McSherry approved the committee's action, and on 2 March the thirty-three officers then assigned to the unit began assembling for work in the Watson West building at Shrivenham. On the 5th, Col. Edgar Lewis was named Chief Planner and Head of the German Section with Colonel Bridge as his deputy.

Colonel Lewis's appointment brought into the unit one of the few American officers who had previously done work on military government organization for Germany. He was also apparently not an advocate of the AMGOT philosophy prevalent in the unit when he arrived. As chairman of a student committee at Charlottesville in the spring of 1943, he had directed the drafting of a plan for Germany that prefigured some later COSSAC and SHAEF concepts. Lewis's committee had envisioned a tactical military government to be used as long as hostilities continued ; some months later COSSAC planning included this same idea. Looking farther ahead than COSSAC did, however, the committee had also proposed retaining territorial military government, which would be installed after resistance ended, under the commanding generals of the field armies as military district commanders. Such an arrangement would limit the scope of the national control authority in Berlin to matters such as communications, transportation, and money and banking, which absolutely required central direction. The committee's report had further projected a pool of trained military government teams similar to ECAD.6

The bent of Lewis's previous thinking was probably somewhat related to his assignment to the German Country Unit, since the AMGOT-Mediterranean approach to the planning for Germany had run into trouble at higher levels even while it seemed to be having a triumphant inception in the SHAEF Special Staff. In February the British War Office had begun pressing for the early creation of a separate Allied control authority to take all post-hostilities planning away from SHAEF. The Director of Civil Affairs, War Office, pointedly asked to have explained the purpose of the German Country Unit as well as the "necessity for the institution" of such a group.7 General Morgan, the SHAEF Deputy Chief of Staff, found reasons to justify the existence of a German unit in SHAEF, but not one with as wide ranging a mission as the planners had set for themselves. Morgan emphasized the need for a handbook on Germany; he furthermore stressed both SHAEF's responsibility to provide advanced training for civil affairs officers and the belief that the "minor machinery" of SHAEF and the Allied control authority should be the same in order to avoid duplication.8 Morgan's explanations were not enough, however, to get prompt

[81]

War Office approval concerning British officer assignments to the German Country Unit, and as of mid-April, only eighteen officers out of the British quota of fifty-one were at work. By then, all the US officers were present plus twenty-four additional men temporarily filling spaces allotted to the British. The shortage on the British side persisted throughout the unit's existence.9 In the SHAEF G-5 reorganization in April the German Country Unit figured primarily as an embarrassment. The revised SHAEF thinking excluded it from military government before the German surrender, and because of the British opposition, its role after the end of hostilities was in doubt. The handbook was all that remained of the unit's original mission. As the planning papers delicately stated, it was "not possible to foresee the exact requirements" for the unit.10 Morale hit a phenomenal low in May when for nearly the whole month nothing was announced concerning the unit's place in the SHAEF scheme other than that the US personnel would henceforth constitute the 6911th ECA Unit in ECAD. When Brigadier Gueterbock on the 5th described the situation as "curious," he was giving voice to a sentiment already widely held in the unit. He did manage to decrease the curiousness somewhat by implying that, as SHAEF's organization for governing Germany after the surrender, the unit existed for an eventuality that was no longer expected to materialize.11 Morale in the unit again improved slightly after G-5, on the 29th, finally announced its designation as the German Country Unit, SHAEF, and its retention under the Operations Branch, G-5, for matters of policy, operations, and planning.12

On 7 June 1944, the day after the Normandy landing, the German Country Unit, having never really fitted into ECAD, began moving from Shrivenham to Prince's Gardens, London. Its arrival in the city coincided with the start of the German V-bomb campaign against England, and in early July, the unit's offices on Exhibition Row were wrecked by a near miss. The bomb hit early in the morning before anyone was in the offices, but five enlisted men were injured on the same day by a bomb that struck the enlisted billets some distance away. Nevertheless in June and July, working in partially demolished rooms without panes in the windows or plaster on the walls and ceilings, the German Country Unit seemed at last to have found its purpose in the war. The handbook had to be finished, not as an exercise but because within weeks detachments might be in Germany and would need it. The unit also became involved in the EGAD reorganization, the regional training program, the assignment of detachment pinpoint locations, and the various "north" and "south" plans for the British and US zones.13

At the same time, once the troops had landed in France and begun moving, no one really expected SHAEF's German Country Unit to last out the summer. The British government had never accepted the estimated six-month period of SHAEF control after the surrender and only very reluc-

[82]

tantly contemplated any SHAEF period at all. No doubt, in considerable part the British attitude stemmed from an unwillingness to see policy-making authority vested in an agency of SHAEF, which in turn took its direction from the Combined Civil Affairs Committee (CCAC) in Washington. By late spring, however, both the British and the Americans realized that getting the Soviet Union to participate in tripartite control in Germany would be more difficult if the United Kingdom and the United States pursued a combined policy in their zones. Brigadier Gueterbock had already strongly suggested to the officers of the German Country Unit in May that they might have a future as members of separate British and US country missions but very likely did not have one as part of SHAEF. For the US contingent in the unit, the denouement began on 17 August when G-5 reassigned some officers to the training cadre of ECAD and some to Headquarters, ECAD, leaving only slightly more than a third under Colonel Lewis to await transfer to the US Group Control Council soon to be formed.14

The one task the German Country Unit had throughout its existence was the writing of a military government handbook for Germany. The job, though a large one, was essentially routine, and the German handbook would have passed into obscurity along with its linear ancestor, the AMGOT "Bible" for Sicily and Italy, and the handbooks for the liberated countries of northwestern Europe had it gone as intended to the military government detachments and not made an unscheduled detour through the White House. Theoretically, the handbook was to be the only document a working military government officer would need in the field, compact enough to fit into a pocket but comprehensive enough to incorporate "all that . . . (he) requires in order to carry out his duty, and no more." 15 During March, April, and May, regardless of its organizational ups and downs, the German Country Unit worked on the handbook. It had completed the third draft by 15 June when an editorial board took over to co-ordinate the work on what was assumed to be the final draft. Several hundred copies of the third draft were mimeographed and distributed within SHAEF and to civil agencies in Washington and London.

The handbook differed from the related compilations, FM 27-5 and Standard Policy and Procedure, in that, while they were broad procedural guides used mainly by staffs in planning, the handbook dealt with concrete military government problems anticipated in Germany. Its outstanding virtue was that it would save the field officer the work and protect him from the pitfalls of having to adapt general procedures and policies to German conditions. This adaptation would be done for him on every foreseeable question in one or another of the three sections of the handbook. In the first section he would find descriptions of the probable conditions in Germany and of the organization and workings of military government. The second section, considered to be the heart of the handbook, contained a chapter each on the twelve primary civil affairs-military government functions, such as food, finance, and education and religion. For the functional specialists each chapter was expanded and issued separately as a manual. The third section contained sample report forms and

[83]

other basic information and the Supreme Commander's proclamation, ordinances, and laws.16

The proclamation, ordinances, and laws-also printed separately in large format for posting-would constitute the legal bond between the Germans and military government. Although not strictly required in international law, the proclamation was assumed to be accepted United States practice.17 Addressed to the people of Germany in the name of General Eisenhower as Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Forces, it declared his assumption of "supreme legislative, judicial, and executive power within the occupied territory"; suspended German courts and educational institutions; and required all officials and public employees to remain at their posts until further notice. The first of the three ordinances defined nineteen crimes against the Allied forces punishable by death. The second ordinance established military government courts, and the third made English the official language of military government. The laws, with gaps left in the numbering system to accommodate future legislation, fell into two classes : those necessary to establish and maintain military government control and those dealing with national socialism. Law No. 1 abrogated nine fundamental Nazi laws together with their subsidiary decrees and regulations and prohibited any interpretation of German law in accordance with Nazi doctrine. Other laws abolished the National Socialist Party, its auxiliary organization, and the use of its emblems.18

On 15 August the German Country Unit had a fourth draft of the handbook ready for final approval and publication. The foreward defined the scope as embracing "the objectives and policies to be pursued by commands and staffs in planning for an operating military government in Germany whether in the mobile, transitional, or static phase [that is, both before and after the surrender]." 19 At the time, CCS 551, restricted to the presurrender period, was still the only directive SHAEF had received, hence the handbook overstepped SHAEF's authority in some degree; but SHAEF had directed the country units to keep the handbook under constant examination and up to date with new policy if any came from the CCS.20 Until the Normandy landing and for some time thereafter, a German collapse or surrender before Allied troops had entered the Reich itself seemed likely; consequently, to develop elaborate plans and exclude this contingency from them would not have made sense.

Even though the CCAC had trouble composing agreed policy papers, there had been no fundamental philosophical disagreement over the treatment of the Germans in either CCAC, in SHAEF, or in the other British and American agencies directly concerned. The American officers, considering the newness of their specialty, had a remarkably homogeneous outlook fostered by The Hunt Report, the military government manual (FM 27-5) , and the schools, Charlottesville in particular. They all had read The Hunt Report, at least in its abridged wartime edition; many had

[84]

listened to lectures by World War I veterans; and the belief that the US administration in the Rhineland had been better than those of the British and French because it was the most benevolent and enlightened had become practically an article of faith. FM 27-5 as revised in December 1943 no longer stated the conversion of enemies into friends as an object of military government, but it predicted that properly conducted military government could "minimize belligerency, obtain co-operation, and achieve favorable influence on the present and future attitude toward the US and its allies. 21 On 15 August 1944 the Civil Affairs Division had a proposed postsurrender directive ready in which it instructed Eisenhower to maintain a "firm, just, and humane" administration. Under this directive, he would be required to destroy nazism and fascism but also to preserve law and order and "restore normal conditions among the population as soon as possible." The economic guide would have instructed him to prevent inflation, control prices, reduce unemployment, and provide emergency relief and housing.22

While the German Country Unit was strongly conscious of the dearth of combined guidance for the handbook, the basic lines of British and US policy appeared to be clear enough. The COSSAC planners had used both FM 27-5 and the Military Manual of Civil Affairs (British) in writing the Standard Policy and Procedure and had not found any glaring conflicts. At the very highest level the President and Prime Minister had made what appeared to be a clear and public statement of combined policy in the Atlantic Charter (14 August 1941) in which they promised the "final destruction of Nazi tyranny" but did not exclude the German people from the better world to be built after the war. CCS 551, the presurrender directive and the only concrete piece of agreed policy guidance that the German Country Unit had, except for its detailed instructions on dealing with nazism, read much like a version of FM 27-5 adapted specifically to Germany. In fact, except concerning nazism, militarism, reparations, and war crimes, the German Country Unit assumed that the policy toward Germany would differ in some degree from that for the other western European countries but would have essentially the same tendency, namely, to provide as much supervision as necessary and as little as possible. Toward midsummer 1944, postwar planning papers then beginning to circulate in the EAC took up the idea of German collective responsibility; however, this concept did not seem to require changes in

[85]

SHAEF's plans beyond the substitution of the term "military government" for all references in the handbook to "civil affairs," which was done by order on 28 July.23 FM 27-5 had already prescribed the term "military government" for use as the over-all designation for civil affairs in enemy territory but had not insisted on its being used exclusively.

In early August 1944, Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau, whose overt involvement in occupation planning had for two years been limited to financial matters and the nomination of occasional Treasury officials for civil affairs appointments, made a trip to Europe. He went to observe the effects of the Treasury's financial arrangements for liberated France; but, as he later said, on the flight over he chanced to read a State Department paper dealing with postwar policy for Germany, and he was filled with misgivings.24 In London he talked with the US representatives in the EAC and discussed the SHAEF plans for Germany with Colonel Bernstein, who had gone from the Treasury Department into civil affairs and had been associated with the German Country Unit from its inception. When Morgenthau returned to Washington he brought with him a copy of the German handbook which, with an accompanying list of his criticisms, he passed on to the President and thus, not unwittingly, precipitated the opening thunderclap of a storm in US policy that would be long in passing.

The errant handbook arrived in Stimson's office on the 26th accompanied by a presidential memorandum which began, "This so-called Handbook is pretty bad. I should like to know how it came to be written and who approved it down the line. If it has not been sent out as approved, all copies should be withdrawn and held until you get a chance to go over it." There followed passages from the handbook pertaining to economic rehabilitation that Morgenthau had singled out as particularly objectionable. "It gives the impression," the memorandum continued, "that Germany is to be restored as much as the Netherlands or Belgium, and the people of Germany brought back as quickly to their prewar estate." The President said he had no such intention. It was of "the utmost importance" that every person in Germany should recognize that "this time" Germany was a defeated nation. He did not want them to starve. If they needed food "to keep body and soul together," they could be fed "a bowl of soup" three times a day from Army soup kitchens. (The first version reportedly read, "a bowl of soup per day.") He saw no reason, however, for starting "a WPA, PWA, or CCC for Germany." The German people had to have it driven home to them that "the whole nation has been engaged in a lawless conspiracy against the decencies of modern civilization.25

The President's idea of what the coming defeat would mean for Germany was not very clear. A year hence most Germans

[86]

would have been happy to have three meals a day from Army soup kitchens, had the Army been able to provide them. In fact, his concept of the German postwar condition was probably no more austere than the authors of the handbook had assumed it would be and vastly brighter than it actually was. Nevertheless, Roosevelt set the whole US occupation policy off on a course that would be difficult to steer and for too long impossible to abandon.

On the afternoon of the 28th, General Hilldring telephoned Smith, Eisenhower's chief of staff, and told him to "get to work right away" suspending and withdrawing the handbook and recalling all copies of several draft postsurrender directives SHAEF had recently sent out for review. He said that "very strenuous" objections had been raised "at the very highest level on the US side." Since neither the War Department nor the Combined Chiefs of Staff had issued any postsurrender instructions, he added, it would be well "to bear in mind in General Eisenhower's own interest" that any instructions SHAEF issued could only apply to the presurrender period. "It appears to us," Hilldring concluded, "that there may be some considerable difference in what we do during the active operational period in the treatment of those who come under control of SHAEF and those measures which we will adopt which come through the defeat of the German Army. Is that philosophy clear to you?" 26 To Smith it was not at all clear, and he said so. The philosophy bothered him less than two practical matters which he bluntly called to Hilldring's attention: first, the troops were approaching Germany and might be there in a few days, and SHAEF could scarcely afford at this point to scrap the handbook; second, "on matters of such importance" SHAEF as a combined command had to receive its orders through the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS).27

A day later by urgent cable the CCS told SHAEF to defer further action on the German handbook pending instructions which would be issued "in the near future." 28 The agreement of the British members in the CCAC to hold up the handbook had been easily obtained. They were not bound to follow the President's wishes even if the memorandum had been shown to them, which it probably had not; but in the meantime, the War Office had expressed its own strong dislike for the handbook which it documented with a list of specific criticisms almost as long as the handbook itself. While the British reaction saved the CAD the trouble of having to engineer unilaterally an about-face on a combined project, the relief was mixed with dismay. The British comments, on close reading, proved to be chiefly concerned with demonstrating that the handbook should not have been assigned to the German Country Unit in the first place and now ought to be done over by the CCAC (L).29

The job of reworking the handbook, however, did not go to the CCAC (L) but to G-5, SHAEF, the German Country Unit having ceased to exist. SHAEF's compelling interest at the moment was to get the handbook cleared in some form and issued before the troops made their way into Germany. G-5 put out a hasty revision dated I September in which it attempted

[87]

to disarm further criticism by emphasizing the work's inconclusiveness with a statement in the preface that "portions should become inapplicable with changing circumstances" and by inserting a section of blank pages as a token of changes to come.30 Although the CCAC, after examining the handbook closely, found it to be far from a bad job and recognized SHAEF's urgent need for something to give to military government officers about to enter Germany, the US membership could not put its imprimatur on a document that did not show some clear and serious effort to incorporate the President's thinking. The solution settled upon was to allow Eisenhower to publish the handbook provided he affixed to the front of each copy a warning, like those on patent medicines, consisting of three principles composed by the CCAC, and had a number of specified revisions made in the text.31

In the list of required revisions, the CCAC tried to tailor the language of the handbook to the spirit of the President's memorandum and to the British criticisms, which in many instances were not compatible. At the same time, the CCAC tried to retain almost the entire substance of the original because it came closer to the current British and American views than another effort from scratch ever could. Since the handbook had no chance of being recognized as definitive of either British or United States policy, most of the revisions had no actual significance; whatever national policy they embodied would be stated more authoritatively elsewhere. Only a few, therefore, are of even moderate historical interest. Among these few, one stands out because it seemed at the time to get at the very heart of the problem with the handbook and because it still illustrates the semantic pitfalls to be encountered in this kind of writing.

In the original handbook version the first paragraph of the Supreme Commander's proclamation had referred to Germany as a "liberated" country and did not mention militarism among the evils that the occupation forces proposed to eradicate in Germany. This omission was easily corrected by inserting a sentence condemning militarism between one concerned with the Nazi party and its institutions and another pertaining to war crimes and atrocities. The use of the word "liberated" in addressing the German people, however, raised problems. The US and British planners were long accustomed to differentiating between "liberated" friendly and "occupied" enemy territory, but the Atlantic Charter promised the Germans, too, a kind of liberation, and the word "occupiers" was ruled out because it had come to be synonymous with "exploiters." Furthermore, the military commands, already feeling trapped by their governments' rhetoric in the unconditional surrender formula, wanted to avoid additional psychological handicaps. The answer found was the sentence, "We come as conquerors, but not as oppressors"-in English at once martial and pacific, forceful and vague. It had the kind of lofty ambivalence the Americans and British appreciated, but not so much the Germans. In German there is no way of muting the connotations of plunder and annexation of territory in the word Eroberer (conqueror) , which the Psychological Warfare Division, SHAEF, hurried to point out when the first copies of the proclamation came out in print.32

[88]

The search for a better word eventually went all the way to the Pentagon's top German translator who substituted ein siegreiches Heer (a victorious army), which to the Germans only emphasized the obvious.33 In English, "We come as conquerors" quickly found a place among the durable quotes of the war.

The three principles, as drafted in the Civil Affairs Division, were ready to be sent to SHAEF along with the revisions in the first week of September, but reconciling them with British views took almost another month. Point One in the CAD version read, "No steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany are to be undertaken except such as may be immediately necessary in support of military operations." Obviously meant to give effect to the President's strictures against any involvement by military government in restoring the German economy, it was also, in a more stringent form, something Eisenhower had asked for earlier in another context (see below, p. 100). On British insistence a second sentence was added in the final version which read, "In accordance with this policy, the maintenance of existing German economic controls and anti-inflationary measures should be mandatory upon the German authorities and not permissive as in the present edition of the handbook." One of the strongest British objections to the handbook had been to the use of the words "will be permitted to continue" with reference to rationing and price and marketing controls. Moreover, the British had not supported Eisenhower's request to be relieved of economic responsibility and had argued that as much of the German economy should be saved as possible.34 As a result, the first sentence of Point One ordered military government to do nothing to support the German economy and the second ordered it to require the German authorities to continue the controls that had sustained the economy through the war.

Point Two went as it was written by the CAD. It read, "No relief supplies are to be imported or distributed beyond the minimum necessary to prevent disease and such disorder as might endanger or impede military operations." Although the disease and disorder (more often unrest) formula was later frequently cited as the most inhumane feature of the occupation policy, no objection to it was voiced in the CC AC because it had long ago been accepted by both the British and the Americans. In its earliest relief planning the CAD had assumed, as the AT (E) Committee also had, that the Army would hold its relief activity to the minimum in liberated as well as enemy territory, not out of insensitivity or inhumanity but because winning the war had to come first.35 The COSSAC planners had proposed not to import relief supplies into enemy territory, "except where military operations or the health of our forces would otherwise be jeopardized." 36 Standard Policy and Procedure established the criteria for relief as "a general breakdown of civil life and spread of disease" for enemy

[89]

territory and "the development of conditions which might interfere with military operations" for liberated populations. CCS 551 used the disease and unrest formula in its text, but in the economic and relief guide, it made the standard of relief for Germany the same as for liberated countries.37

The first sentence of Point Three, written in the CAD, read, "Under no circumstances shall active Nazis or ardent sympathizers be retained in office for purposes of administrative convenience or expediency." The handbook had contemplated, as had anyone who had given thought to the subject, the necessary use of some Germans with unique technical skills even though they were Nazis. Point Three closed the door on "active Nazis and ardent sympathizers" without defining either one. The two concluding sentences, both British in origin, added : "The Nazi Party and all subsidiary organizations shall be dissolved. The administrative machinery of certain dissolved Nazi organizations may be used when necessary to provide certain essential functions as relief, health, and sanitation." 38 Point Three is notable as the first outright plunge into the semantic jungle of denazification. This point rejected expediency where individuals were concerned but appeared to condone it at least in the case of some organizations. (An attempt was made later to correct this apparent contradiction by establishing the second part as a separate fourth point.) The third principle also assumed that the categories "active Nazi'' and "ardent sympathizer" would be as self-evident on the ground in Germany as they were across the Atlantic in Washington.

When the CCS transmitted the three principles to SHAEF on 6 October, it pronounced the first SHAEF revision of the handbook "greatly improved but not yet satisfactory" and authorized a minimum distribution provided the principles were prominently attached at the front.39 A second revision was completed in mid-October, just in time to be put out of date by EAC decisions on the zones and control machinery which made another revision necessary in December.40 Once it had been printed and distributed in December, the handbook promptly faded from the higher echelons' view. As an officer in SHAEF stated during the controversy, ". . . nobody ever reads handbooks anyhow, except very junior officers whose subsequent actions can have very little effect." 41 The three principles, on the other hand, had a life of their own. They constituted, presumably, an expression of War Department policy based on the President's desires, and as a CCS document they became agreed combined policy, of which there was and would be very little. As such they had the force of a basic directive in all matters to which they applied. Viewed in this light, they appear severe, even harsh. Studied individually, however, they reveal an ambivalence almost too striking to be accidental; even aside from the British contributions, the severity was at least as much rhetorical as real.

[90]

With the invasion imminent in the late spring of 1944, no decision had yet been reached in the EAC on the mechanics of tripartite control in Germany after the surrender. Independently, the JCS in Washington and the British authorities in London had concluded early in the year that, initially at least, the three commanding generals would head a central authority to which the JCS gave the name "Control Council" and the British, "Control Commission." 42 Both had accepted the three phases used by SHAEF-a military phase during active hostilities, a transitional phase after the surrender, and a phase of permanent Allied control-but they tended to disagree on the duration and form of control appropriate to each phase. The JCS saw the first two phases as essentially military and possibly extensive; the British wanted them to be brief, even fleeting, and wished to move into permanent direct control by the governments almost immediately. The words "council" and "commission" became symbolic embodiments of these divergent views and adherence to them became, hence, almost a point of national honor.

As D-day approached and passed, Eisenhower had a problem. As Supreme Commander he had a military government organization that considered itself fully capable of governing as much of Germany as might fall to the British and American combined forces; however, as Commanding General, ETOUSA, he had not even an embryo organization to head military government in a US zone or to form the US element of a control authority. His own preference was for a permanent combined administration in the western zones, but in this opinion he was out of tune with both Washington and London.43 The JCS and the President were convinced of the necessity of separate zones to protect the national interest. The British had already begun planning their element of the Control Council/Commission in late 1943 and by early 1944 had set up one segment of it, the Control Commission (Military Section) (CCMS).44 In the EAC, the British delegation proposed on 2 May 1944 that the Control Commission be prepared to take over in the "middle" (second) period "at the earliest possible date" and that a British-American-Soviet team for the purpose be formed in London soon.45

The US delegation in the EAC began work in May on its own proposals for control machinery and presented a plan on 8 June in which it called for the early establishment of Control Council cadres.46 The planning committee of the US delegation also drafted principles relating to the nature and functions of a control council. On 19 June these principles began the process of clearance through the delegation's military advisers, submission to Washington, and eventual presentation in the EAC.47

[91]

SHAEF always followed what went on in the EAC closely and especially so beginning in May when the British showed themselves determined to set up their Control Commission as the principal posthostilities planning agency for Germany. In May, Eisenhower brought General Wickersham into SHAEF to assume the role of deputy chief of the European Allied Contact Section in addition to his duties as War Department adviser to Ambassador Winant in the EAC. (Wickersham had been transferred to Winant's staff in January.) The Control Council/Commission plans, especially in the British version, could easily result in another AMGOT, which by then was an anathema in SHAEF policy, though not necessarily to all of the individuals in G-5. As a practical matter, however, Eisenhower had also to consider that once the invasion had succeeded, the end for Germany might come fast; furthermore, as of June, his own authority to plan for the time after surrender as commander of the British and US forces was at best doubtful. Worse, as the prospective chief US representative in a tripartite administration, he had no resources for planning and none existed anywhere else other than in the EAC, which so far had produced very little.48

General McSherry, chief of the newly created Operations Branch, G-5, SHAEF, advocated immediate creation of a tripartite control organization, arguing that time was short. McSherry, who had earlier defended the AMGOT system, also believed that the military commanders ought to be relieved of all military government responsibilities as soon as the tripartite body could be established in Berlin.49 As Commanding General, ETOUSA, however, Eisenhower was less concerned with the need for a tripartite planning agency than with the possibility that the EAC might bring one into being before he had anything to contribute to it. The Russians were unpredictable. Their element might never appear-as in fact it did not-on the other hand, it might show up one day fully organized and ready for work. The British had the Control Commission (Military Section) (CCMS) and half a dozen groups in the Foreign Office and Cabinet Office waiting to be converted into control sections. ETOUSA had nothing.50

On 20 June, Wickersham left by plane on a special mission to Washington carrying with him a memorandum from Eisenhower to the JCS. The mission was a delicate one. More was involved than just creating another planning staff. SHAEF as yet had no authority to plan for the period after surrender. The EAC had such authority, but the surrender might very well come before the EAC completed its work; consequently, SHAEF was the logical and only body capable of instituting and conducting military government in Germany during the initial postsurrender period. To fulfill this potential, SHAEF would have to have a hand in the postsurrender planning and be the EAC's executive agency then, as it already was the CCS agency for the presurrender period. The trick was to find a place for the Control Council, which would be both a necessity and an inconvenience and which would have to be both fostered and restrained. How such a task would be accomplished was, no doubt, what Wickersham went along to explain. Eisenhower

[92]

implied that it would be done through controlled development. He asked to have appointed under him as Commanding General, ETOUSA, a deputy chief for the Control Council and a nucleus group to consist mostly of a counterpart of the British Control Council element, the CCMS. Except for a token military government staff the US element of the Control Council would concern itself exclusively for the time being with planning for German demobilization and disarmament.51

In Washington, Wickersham successfully shepherded Eisenhower's memorandum, which in the process acquired a JCS number (923/1) , through twenty-five offices including those of the President and General Marshall.52 After he returned to London in mid-July, Wickersham turned over his duties in the EAC to Brig. Gen. Vincent Meyer and worked full time on organizing a military section for the projected Control Council, modeled on the British CCMS. When Brig. Gen. John E. Lewis arrived at the end of the month, a cadre of US Army, Navy, and Air Force officers assembled in Norfolk House, London, which also housed the British CCMS.53 The two groups, though expecting to be merged, maintained a scrupulous separateness while awaiting a Soviet contingent. Later, however, when, on Wickersham's urging, the Soviet delegate to the EAC, Ambassador Gousev, sent a description of the organization and its personnel requirements to Moscow, the reply stated curtly that the Soviet Union could not spare officers from combat.54

Formal JCS approval arrived on 5 August. It authorized Eisenhower to set up a nucleus planning staff to be known as the US Group Control Council (Germany) and named Wickersham as the acting deputy to the chief US representative on the Control Council (not yet appointed) . The US Group's mission would be to plan for posthostilities control in Germany in accordance with EAC directives or, in the absence of such directives, in accordance with US views on subjects pending before the EAC. The US Group would belong to ETOUSA not to SHAEF, but in Germany, until the combined command terminated, it would be subordinate to SHAEF "in implementing on behalf of the US and U.K. governments policies agreed upon by the three governments." 55

The JCS gave Eisenhower more than he had asked for, in effect a directive to begin setting up a full Control Council element, not just a counterpart CCMS. Group Memorandum No. 1 of 10 August took this authorization restrainedly into account in creating three divisions within the US Group Control Council: the Armed Forces Division, charged with planning for German disarmament, disposition of the German armed forces, demilitarization, care and repatriation of Allied prisoners of war, and intelligence with respect to German research and inventions; Military Government Division A, to deal with economics

[93]

"in a broad general sense" ; and Military Government Division B, to handle political matters in the same fashion.56 The nucleus of the Armed Forces Division already existed at Norfolk House under General Lewis. The military government divisions did not come into being until later in the month when officers from the disbanded German Country Unit were assigned and chiefs were appointed, Brig. Gen Eric F. Wood for Division A and Brig. Gen. Bryan L. Milburn for Division B.57

From the moment of its inception the US Group Control Council constituted the wave of the future for military government in Germany. The United States accepted the principle of tripartite policymaking, and the JCS had assigned to the US Group, along with the British and the supposed Soviet groups, the mission of converting general policies drafted in the EAC into operational plans. Presumably, once the EAC began to produce and the Soviet element of the Control Council put in an appearance, there would not be much scope left for SHAEF. Already in mid-August the British Chiefs of Staff proposed that the US and British groups begin working together at once with what guidance was available and refer questions they could not resolve to the CCAC (L).58 The British proposal would in one sweep have taken postsurrender planning-and probably presurrender planning as well, since the two had to conform to each other-away from both the CCAC in Washington and SHAEF. Had the Russians come, some such development could hardly have been avoided. The actual events, however, prompted McCloy to move quickly in the CCAC to get an interim postsurrender directive for Eisenhower and thus affirm his and the CCAC's mandate for the duration of the combined command. (See below, p. 101).59

Henceforth the going would not be easy either for the CCAC or for SHAEF; but SHAEF had, no doubt, known from the start the risks associated with calling the Control Council even into shadow existence. Furthermore, SHAEF was itself a potent organization. It was the actor on the stage and the Control Council the understudy in the wings. Both were powers but not yet equal powers. In an agreement on 23 August, later nicknamed "the Treaty of Portsmouth" by the Control Council staffs, SHAEF established its relationship with the Control Council Staffs. Before the German surrender the British Control Commission Staff would be responsible to its own government and the US Group Control Council to Eisenhower as Commanding General, ETOUSA. After the surrender, until the combined command was terminated, both would function under Eisenhower as Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force. Before the surrender the control staffs would have no executive authority. SHAEF, however, would adjust its policies to conform with the long-term plans made by the Control Council/Commission in accordance with EAC directives.60

In September, when for a while the occupation of most of Germany, including Berlin, seemed likely, SHAEF also undertook to regulate the posthostilities relation-

[94]

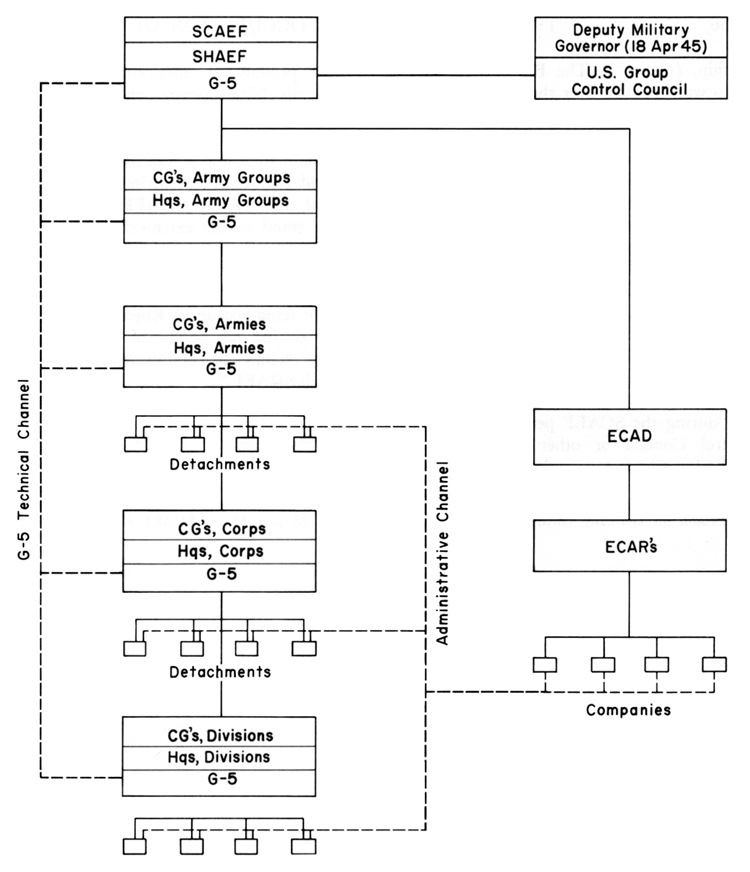

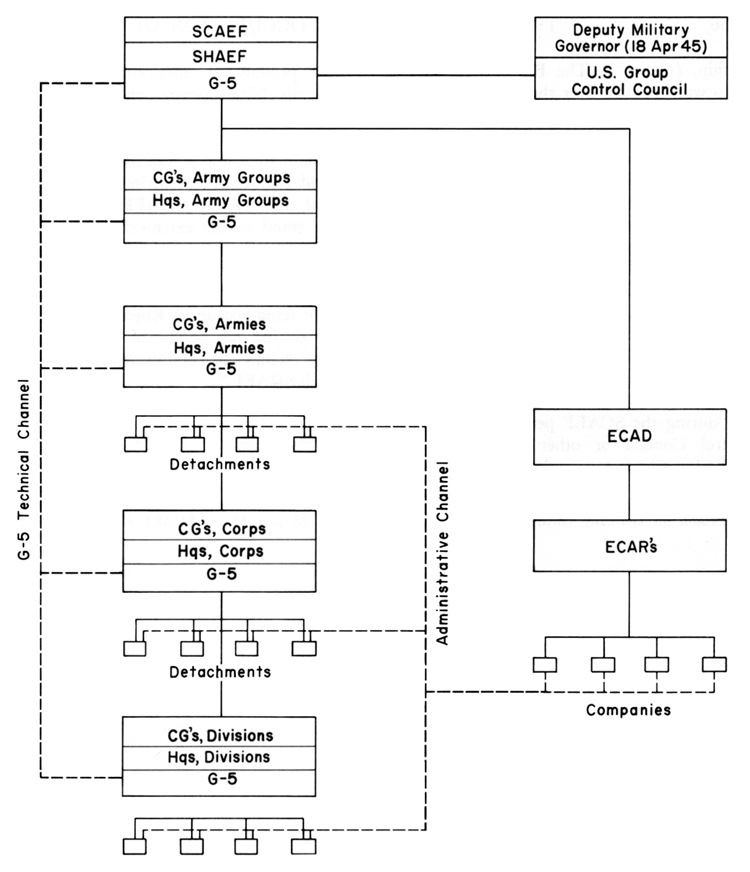

CHART 1-U.S. MILITARY GOVERNMENT RELATIONSHIPS MOBILE PHASE, SEPTEMBER 1944-JULY 1945)

[95]

ship. (Chart 1) The British were known to want to turn over the administration to the control bodies immediately. "The US Group Control Council," as SHAEF blandly stated, "it is believed . . , considers that both the military government of Berlin and the provision of necessary machinery at ministerial level are the responsibility of SCAEF during the initial period." SHAEF announced itself as sharing this opinion and added that the control staffs "must be integrated [including the Soviet element if British and US troops reached Berlin first], must be at SCAEF's disposal, and must be under his command . . . . At no time," SHAEF added, "during the SCAEF period will any Control Council or other committee be in Berlin that is not under his command." 61 British protests, if any, concerning the Americans' blithe assumption of authority over a separate British staff have not been found. Perhaps there were none; September was a tumultuous month in Washington and London. Nevertheless, toward the end of the month SHAEF relaxed its earlier stand to the extent of agreeing to permit a small ministerial control team of Control Council/Commission officers to enter Berlin with the SHAEF forces, provided it remained under Eisenhower's command during his period of responsibility and its channel of communications passed through SHAEF. 62

[96]

Return to the Table of Contents