CHAPTER XII

The Rhineland Campaign, 1945

On New Year's Day 1945, eight German divisions attacked south out of the Saar attempting to trap Eisenhower's thinned-out flank in Alsace. In the Ardennes, the Battle of the Bulge was at its height. During the next few days the fighting around Bastogne was as bitter as any since D-day. On the other hand, as for getting to his strategic objective, Antwerp, or anywhere near it, Hitler no longer had a chance. His chief of the Army General Staff, Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, had told him as much at Christmas and had also told him that the Russians along the Vistula were ready to unloose their most powerful offensive of the war. Calling the report on the Russians a colossal bluff, however, Hitler ref used for a week to concede that the breakthrough to Antwerp could not be made. He then waited five more days before taking his spearhead force, Sixth Panzer Army, out of the front in the Ardennes, and took another week making up his mind to dismantle the rest of the buildup in the Bulge.

When Hitler returned to Berlin from his Western Front headquarters on 15 January, the Vistula line in Poland was collapsing. Two weeks later the Russians were on the Oder River at Kuestrin, thirty-five miles from Berlin. On the 26th, Marshal Georgi K. Zhukov reportedly told Stalin he could be ready to attack toward Berlin in four days.1 In the west, the U.S. armies were barely back to the line in the Ardennes that they had held in December, and in Alsace the Germans were still fighting hard. Who would arrive in Berlin first seemed not to be a question anymore. At the speed they had moved in January, the Russians could have been first on the Rhine.

In and around Aachen the occupation was nearly four months old. Most of the civilians in the city were living in cellars, air raid shelters, or bunkers without heat, electricity, gas, or running water. The main thoroughfares had been cleared for military traffic; elsewhere the snow cover had softened but could not entirely conceal what was "a fantastic, stinking heap of ruins." 2 Cabbage soup and potatoes were the standard diet. On the ration, each adult was entitled to half a pound of meat and bones, a quarter pound of butter, and one loaf of bread a week, when available. In Stolberg, the second largest occupied community, three-quarters of the population was eating at soup kitchens and getting 900 to 1,000 calories a day. The few trucks owned by the cities were being used to collect food in the countryside. To pay for city services, such as they were, and make pension and relief payments, Aachen was selling off the abandoned property of evacuees.3

[178]

The economy was prostrate. In Stolberg no stores were open. The municipal labor office in Aachen had registered all able-bodied inhabitants for work at clearing rubble and repairing roads. The work was unpaid, and for one job on which 200 workers were called, seventeen appeared, a typical turnout. For all jobs the only workers to be found were boys under sixteen or old men. Military government was under orders not to concern itself with reviving the German economy, but it had an interest in coal, which in winter ranked next to food as a necessity of life. The Aachen mines had formerly employed 20,000 men. In February 1945 there were 1,000 working in the mines; and they had a 33-percent rate of absenteeism, because the ration was not enough to sustain a man at heavy work in the mines, and miners could not buy anything with their pay. The workers easiest to secure and most reliable were those employed by the Army. Army employees received a noon meal-something which was going to prove a major attraction for many Germans in the coming months and years. The meal was prepared and served on the job partly for the sake of economy but also because if the worker was allowed to take the food home, it usually went to his family.

The civilians' feeling of relief at being out of the war was beginning to give way under the hardships of the winter to a subdued resentment. 4 But the resentment was not at a level approaching resistance to the occupation. Of 487 cases tried in Ninth Army military government courts up to the end of January, three-quarters were for minor circulation and curfew violations. In the two most serious cases, one defendant got twenty years for spreading rumors prejudicial to Allied interests and the other got fifteen years and a 10,000 Reichsmark fine for disobedience to military government orders. The other cases were sometimes interesting but hardly evidence of a threat to military security. Even harboring German soldiers, a serious crime, usually turned out not to have been motivated by malice. In one instance a mother wanted to keep her son at home ; in another a homeowner needed someone to fix his house and the soldier was handy with tools ; and in a third a soldier turned himself in after a lovers' quarrel with the woman with whom he was living. He went to a prisoner of war camp, she to jail for fifteen months. In Schaffenberg, outside Aachen, a man was sentenced for holding a public meeting. He had hired a carpenter to repair his house and a crowd had gathered to watch the carpenter work. In Brand a summary military government court fined a civilian 100 marks for calling the Buergermeister a thief and a Nazi. The review board reversed the sentence on the ground that civilians should be encouraged to comment on public officials.

Nonfraternization cases against civilians continued to trouble the courts. In Stolberg, a summary court found three women guilty of acting in a manner prejudicial to the good order of members of the Allied forces. The military policeman who made the arrest stated he had entered an apartment and found the three listening to a phonograph with two US soldiers. The review board took the position that the soldiers might have been guilty of fraternization, but in the absence of immoral conduct, the women could not be charged. In Aachen, a summary court found two girls guilty of inviting two American soldiers into a house marked "off limits." A

[179]

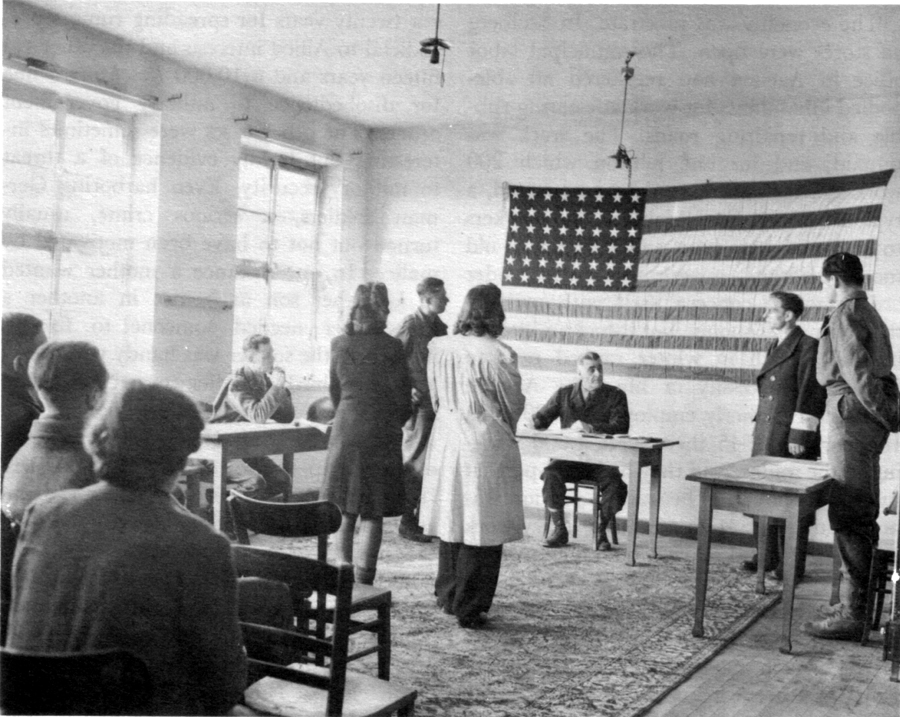

TRIAL IN A MILITARY GOVERNMENT COURT. The two German women were convicted of illegal border crossing.

review board set aside the convictions because the off-limits signs had been posted solely to prevent fraternization and therefore constituted an attempt to shift responsibility for nonfraternization from the military to civilians.5

In January, Aachen became the first city in the occupation to have a licensed newspaper, the Aachener Nachrichten. Partly for the experience and partly in the belief that it was time to get on with re-educating the Germans, the Psychological Warfare Division sent a press control team into Aachen to set up a plant and find a licensee. The plant did not prove to be much of a problem. The building and press of the former Aachen newspaper had survived the battle fairly well, and some newsprint was on hand. Finding a publisher was

[180]

more difficult. The press control officers interviewed every newspaperman in Aachen but could not come up with one who, besides being professionally qualified, had an unclouded political past. Determined not to compromise politically for the sake of competence, they finally settled on a 70 year-old ex-composing room foreman, Heinrich Hollands, who had been unemployed since 1933 because he was a Social Democrat. Hollands had no experience at writing or editing and neither did the other Germans on the staff ; so for the first months the paper was mostly a product of the US and British officers on the press control team. SHAEF eased its restrictions on what could be printed to permit local news but not features or editorials, which nearly confined the paper to the stereotype format of Die Mittedungen. Hollands had other troubles as well. The electricity went on and off, and when it went off the metal in the typesetting machines hardened and had to be reheated; furthermore, the curfew interfered with distribution and newsgathering. The local news helped military government to stifle rumors but sometimes inadvertently increased discontent. The people of Stolberg, for instance, began to complain when they found out that the curfew in Aachen was an hour later than theirs and when they read that the Aachen residents were getting extra sugar and marmalade rations.6

Oberbuergermeister Oppenhoff entered his third month under the occupation in Aachen in January. So far he had survived the threatened Nazi vengeance and had become almost a hero by volunteering to stay in the city through the worst of the Ardennes offensive, an act that may have been more dangerous than he imagined since Hitler at one time was close to switching the objective from Antwerp to Aachen. But Oppenhoff had also become a political liability. His appointment ranged back to the days when a recommendation from the Catholic clergy was the best a man could have, and he had the backing of the Bishop of Aachen. But a closer look revealed that the Church had been not so much anti-Nazi as neutral and, having so survived Hitler, was inclined to remain the same during the occupation. 7 Oppenhoff and his fourteen department heads, all his choices, proved to have a similar bent. Except for one nominal party member, they had not been Nazis, and like Oppenhofff, the Gestapo had from time to time had an eye on them; but they had apparently not sacrificed or risked very much during the Nazi regime. In fact, all of them had prospered. Several, including Oppenhoff, prided themselves on having rejected the war and avoided military service. Their method, however, had not been one to inspire in American minds much confidence in their motives. They had helped each other-as they sometimes seemed to be doing again in the city government-into draft-exempt managerial jobs in the Nazi-owned Veltrup armament works in Aachen.8

Politically the men in the Aachen city administration baffled and chagrined the

[181]

Americans who had come into Germany expecting to decide a clear-cut issue-democracy versus Nazi totalitarianism. These Americans felt that every German who was anti-Nazi must be either a democrat, a willing convert to democracy, or at worst a Communist-the last, in the spirit of the wartime alliance, being equated with a democrat. Oppenhoff, by his own definition, was anti-Nazi, but he was also quite frankly antidemocratic, and he admitted to having chosen a staff and appointed city workers whose views agreed with his own.9 He was an authoritarian, apparently of the Bismarckian school. Some of his colleagues were proponents of the Staendestaat, a semifacist class state of the kind the Austrian chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss had organized in Austria in the early 1930s. Oppenhoff disliked fanatical Nazis but saw nothing wrong with employing those who had changed their minds or who had joined the party for business or professional reasons.10

Although disenchantment with Oppenhoff's administration set in early, the sometimes peculiar circumstances of the time gave him a surprisingly solid hold on his office. Competent non-Nazis were among the rarest commodities everywhere in Germany, not only in Aachen ; in the managerial and professional groups they were practically nonexistent. In Strassburg, 6th Army Group captured the personnel files of the Deutsche Aerztebund (medical association) of Land Baden. Of its membership, which comprised all of the doctors and dentists and many of the public health officials in Baden, less than a quarter had no or only slight party connections.11 The medical profession had one of the highest percentages of Nazis, but law, teaching, and public administration were not far behind. Bona fide political opponents of the regime, if they had survived at all, were generally old men, like Hollands. Oppenhoff and his colleagues were competent, perhaps irreplaceable, and consequently appeared indispensable, to the Americans more than to the Germans. To their fellow Aacheners they represented a new elite, not of money (Oppenhoff's salary was 450 marks a month) or real power (the Americans held the power) but of survival. They had eluded the Nazis painlessly and somewhat profitably and they seemed to be handling the consequences of defeat in the same way. They were not living elegantly but they fared a great deal better than the average cellar or bunker dweller. To the occupation forces, they represented stability. The tactical commands in Aachen changed from week to week and, in crises such as the Bulge, sometimes from day to day. Within six weeks in December and January, the over-all command shifted from First Army to Ninth Army and then back again; the military government detachment had three commanders before the end of December. By the time Oppenhoff had been in office three months, he knew more about running Aachen under the occupation than any of the Americans.

Oppenhoff himself was no problem. He and all the Germans who worked under him served entirely at the pleasure of military government and, whatever their politics, executed only American policies. He was, however, a reminder that despite all planning, the purpose of the occupation

[182]

was still obscure and the method of achieving it in doubt. To destroy the Nazi regime was an often stated United Nations war aim dating back to the Atlantic Charter; but did this policy mean the elimination of every party member, even at the price of inconvenience to the occupation forces? Military government had assumed that as long as hostilities continued, its first responsibility was to the combat commands, which would benefit most from an orderly and efficient civil administration. Was denazification to be pushed to the point where it might impair military government's effectiveness and so affect the interests of the troops? Men like Oppenhoff and his colleagues raised a still more difficult question : Was it the business of the occupation to bring democracy to Germany? The Americans considered themselves individually and collectively as natural apostles of democracy. The occupation plans were devised to demonstrate, in the court system for instance, the differences between totalitarian and democratic methods. Neither the policy nor the plans, however, provided for an active democratization program. On the other hand, democratization was so compellingly logical an objective, so much what the war ultimately was all about, that it was bound to become the standard against which the occupation was measured.

The Psychological Warfare Division, SHAEF, did not have the same priorities and responsibilities as military government. Its job was to create an image of the occupation in the German mind, and to do so PWD wanted to get on with the business of democratization. For this purpose, the Oppenhoff administration was not ideal raw material. In January, three captains from Psychological Warfare, Saul K. Padover, Paul Sweet, and Lewis F. Gittler, investigated the Aachen city government and were dismayed. Their report charged military government with having allowed a new elite to emerge-one "made up of technicians, lawyers, engineers, businessmen, manufacturers, and churchmen," and one which was perhaps not Nazi but certainly did not fit the American picture of democracy.12 The report, according to Padover, reverberated throughout the European Theater of Operations.13 The three captains from PWD had signaled the arrival of a powerful ally for radical denazification, the traditional American democratic idealism.

On a staff tour in January, however, Brig. Gen. Eric F. Wood, director of the Prisoner of War and Displaced Persons Division, US Group Control Council, found the trend in 12th Army Group G-5 to be away from a rigid interpretation of the denazification provisions of JCS 1067. The G-5 believed that some Nazis would have to be used because otherwise the field commanders could not be given what they wanted most from military government, an efficient civil administration. Experience so far, the G-5 officers pointed out somewhat ruefully, had shown that most local Nazi officials had acquired their positions through experience and ability, not by virtue of party membership alone.14 The trend noted by General Wood was short lived. The Aachen experience had demonstrated how difficult it was to defend the appointment of even some non-Nazis. The newspaper correspondents were still concentrating on the fighting war, but at least

[183]

one, Max Lerner, writing for the New York paper PM, had already echoed the criticism expressed in the PWD's report on Aachen.15 In early March, 12th Army Group ordered all Nazis removed from public offices and other positions of trust and influence. A few weeks later, 6th Army Group followed suit.16

In Aachen, First Army began weeding out the city's administration after it resumed control in February. Oppenhoff was regarded as being of dubious value but was not dismissed.17 On Sunday night, 25 March, while Oppenhoff was visiting his neighbor, Herr Faust, whom the Americans had recently removed as Buergermeister for Industry, three men dressed in German paratrooper coveralls entered Oppenhoff's house. They awakened the maid and ordered her to fetch him home. When he returned with Faust, they told him they had jumped from a plane, were on their way back to the German lines, and needed food and shelter. According to Faust, Oppenhoff objected that aiding them would jeopardize his position with the Americans and urged them to surrender. When an argument developed, Faust slipped away-to get help, he said. The next morning Oppenhoff's body was found crumpled up in the hallway. He had been shot through the head. During the same night, a tank destroyer unit billeted near Oppenhoff's home discovered that its telephone had gone dead. Two men sent out to look for a break found the line had been cut. The officer in charge then sent out a third man to stand guard while repairs were made. While the first two were working, the guard saw three men walking toward him from Oppenhoff's house. When he ordered them to halt they turned, ran into some bushes at the side of the road, and disappeared. A search the next morning turned up a German belt and a musette-bag hanging from a fence nearby, apparently abandoned after it became entangled in the wire.18

Oppenhoff died as many Germans did that spring, unmourned and without many questions asked. The Americans found it hard to see Oppenhoff as an anti-Nazi martyr, and one favorite theory was that his disgruntled and recently discharged colleagues, of whom Faust was one, had committed the murder.19 Six months later, after the war was over and Oppenhoff nearly forgotten, intelligence investigators uncovered the true story. The order for the murder had come from Himmler and been carried out by border police to set an example for the Werfwolf, the allegedly spontaneous, Nazi-sponsored, German guerrilla and underground resistance organization.20 The staged killing, ordered in January and planned by an SS general as if it were a major operation, was probably the Werwolf's most sensational achievement.

For the detachments sidetracked in the army military government centers, the winter seemed worse than the previous one in

[184]

Shrivenham. The front had not advanced any farther into Germany after November. Meanwhile, the pinpoint assignments had changed so often to keep pace with shifts in plans that it was hard to believe anyone was going anywhere. The latest strategy gave the priority to Montgomery's army group which included only the US Ninth Army. Third and Seventh Armies apparently might be parked on the German border indefinitely, and First Army's prospects were not much brighter. In the third week of February, Ninth Army, the one with the most substantial mission, was standing on the bank of the Roer River waiting for the water to go down. The Germans had opened the dams upstream and flooded the valley down to the Meuse. First Army had taken the dams, but the Germans had done their work well and blown the gates in time to get maximum effect from the millions of tons of water pouring into the valley.

Nevertheless, the dams were no longer a threat. The flood crested, and when it began to recede, the war changed. In the early morning darkness, behind a 2000-gun barrage, Ninth Army crossed the Roer on 23 February. Nine days later the army had a spearhead on the Rhine opposite Duesseldorf. First Army joined in on the south and at the end of the first week in March got what Ninth Army had wanted and not found, a bridge on the Rhine, at Remagen. Against crumbling German resistance, Third and Seventh Armies then cleared the southern Rhineland during the first three weeks of March.

Ninth Army found scarcely a soul in the first ten miles east of the Roer but had uncovered half a million civilians by the time it reached the Rhine. Except for the evacuated zone along the Roer and the cities where the bombing had caused many inhabitants to seek safer places, more Germans were staying home this time, with Nazi party blessings. The Nazi leadership did not even try to conceal its nightmare a refugee wave raised by the Russians in the east meeting a similar wave from the west somewhere between the Rhine and the Oder. If such a meeting took place, nothing would move in Germany, military or civilian. The Gauleiters had encouraged the civilians, women and children especially, to stay, excepting only those whose skills could give advantage to the enemy.21

Ninth Army, advancing from Aachen northeastward toward the Rhine, had the first look at the Germany of 1945, and it was a dismal sight. Detachment I3G2 entered Juelich on the third day. Lying on the right bank of the Roer, the city had been bombed from the air and blasted by artillery. The people were gone. The physical destruction was put at 100 percent, probably a wartime record for cities in Germany. What the bombs had spared, the shells had churned into complete uselessness. With nothing to govern, the detachment turned to directing traffic. The other communities less than ten miles beyond the Roer were in a similar, if not quite as bad, condition.

Muenchen-Gladbach, about halfway between the Roer and the Rhine, was a different case. It was a study in contrasts-some districts badly damaged, others almost intact except for the windows-the work of the air bombardment. Craters in the streets showed where recent bombs had hit. Gravel patches revealed where older craters had been. Buildings were sliced in two, and frequently where a wall had col-

[185]

lapsed, the furniture could be seen in place in rooms on upper floors.22 The walls left standing were covered with slogans: Dein Gruss-Heil Hitler! (Your Greeting-Heil Hitler !) ; Tapfer und Treu! (Brave and Loyal) ; Die Front fuer die Heimat! Die Heimat fuer die Front! (The front for the Homeland ! The Homeland for the front !) ; Erst jetzt Recht! (Now more than ever !) . Here and there, grim-faced older civilians could be seen painting out the slogans with whitewash.

In Krefeld on the Rhine, 100,000 of the 169,000 population had stayed behind in the huge concrete air raid shelters to await the invaders. As soon as the front passed, more inhabitants began drifting in from the countryside. The local newspaper, the Rheinische Landeszeitung, had published its last issue on 1 March, the day before the Americans came. Its headline had read, "Enemy Attempts at Breakthrough in the West Repulsed." The Landeszeitung building was among the few still standing in the center of the city, and its roof was gone. The local Labor Front chief had had an apartment inside. He had obviously left in a hurry-, The breakfast table was set, and his personal stationery was in place in his desk. The street outside had been called the Adolf Hitlerstrasse since 1939. Within hours the residents had reverted to calling it Rheinstrasse. In some places, civilians looting abandoned stores and homes fell to arguing among themselves, oblivious to the American tanks and trucks rolling east. 23

Ninth Army's Psychological Warfare Section took the first of innumerable public opinion samplings in Muenchen-Gladbach a few days after the occupation began. The Germans professed to be relieved that the Americans had come, because the occupation meant an end to the bombings. One fifteen-year-old boy added that for him it meant he could play soccer and not have to attend Hitler Youth meetings; and he liked American chewing gum. Many inhabitants also professed to be anti-Nazi for various reasons. Some claimed religious objections. Others seemed simply to be unhappy that after all their sacrifices, Hitler had lost the war. Some wanted to reserve judgment until they saw how the Americans treated them. Nearly all said they expected hard times. Nevertheless, they complained about the rations they were getting and about having to give up their homes to troops.24

The workhorses of military government on the move were the I detachments, composed of three or four officers apiece, five enlisted men, and two jeeps with trailers. Except in the big cities, these detachments represented the occupation to the Germans, at once the harbingers of a new order and the only stable influence in a world turned upside down. They arranged for the dead in the streets to be buried, restored rationing, put police back on the streets, and if possible got the electricity and water working. They provided care for the displaced persons and military government courts for the Germans. If troops needed to be billeted, they requisitioned the houses. If the army needed labor, they secured it through the labor office. Under the more stringent denazification directives put out in March, they were responsible for getting everything done without using Germans who were

[186]

U.S. OFFICER SWEARS IN A BUERGERMEISTER AND FIVE POLICEMEN

tainted by nazism. "Busy" was the word that described these detachments best-busy with getting local government running again and with streams of Germans reporting to be registered, wanting favors, wanting passes, or reporting rapes and looting, confident that the omnipotent military government would be able to ferret out the guilty from among thousands of soldiers.25 For the civilians, living and eating and staying out of jail all depended on a military government officer's signature on their registration cards and on any passes they

might need to be out during the curfew hours or to travel beyond the three-mile limit. One detachment commander claimed to have signed his name 540,000 times in less than a month.26

Since, in an opposed advance, predicting when specific localities would be reached was impossible, the armies sent out spearhead detachments in the first wave -I detachments whose pinpoint assignments were east of the Rhine. Their job was to move with the divisions in the front, stopping only long enough to post the procla-

[187]

A SPEARHEAD DETACHMENT AT WORK

mations and ordinances, issue circulation and curfew orders, and remove the most obvious Nazis. They sometimes appointed an acting Buergermeister who would then frequently have to be left to struggle with the new rules on his own until the next unit came along and, as often as not, dismissed him for incompetence.

One spearhead detachment was I11D2, commanded by Capt. Lloyd La Prade and pinpointed for Landkreis Friedburg north of Frankfurt. In the first week of March, I11D2 crossed the Roer River behind First Army. On the 9th, the detachment took over Bruehl outside Cologne, appointed a Buergermeister, received orders on the same day to double back to Euskirchen, and on the way was diverted to Linz am Rhein in the Remagen bridgehead. Sunday morning, 11 March, the detachment ran the "hot corner" at Remagen and crossed the bridge safely, becoming the first detachment across the Rhine. La Prade set up his headquarters in the town hall at Linz, which happened to be a mile upstream from the bridge and directly in line with it. The German planes on bombing runs came in low overhead, and on the second day one dropped its bombs short, wounding one officer and an enlisted man. On the

[188]

29th, having counted 200 bombing sorties and evacuated some thousands of Allied prisoners of war and displaced persons to the west side of the river, I11D2 turned Linz over to its assigned detachment and headed south to join Third Army, which was then closing in on Frankfurt. Four days later, after helping to quell riots among political prisoners at Diez and Butzbach near Frankfurt, the detachment moved to its station at Friedburg.27

In the big cities the pinpoint detachments moved in immediately, sometimes before the fighting ended. First Army began clearing Cologne, the largest city in the Rhineland, on 6 March, and Detachment E1H2 arrived on the 9th. At the last minute before the Americans came, the Nazi Gauleitung had sent criers through the streets directing the women and children and men over sixty to cross over to the east side of the Rhine ; but, except for party big shots who left wearing Wehrmacht greatcoats over their party uniforms, few followed the directions because they would have had to go on foot with only the possessions they could carry in their hands. Some, women and children in particular, had left earlier either to escape the bombing or avoid the occupation. First estimates put the number who stayed at 100,000 to 150,000, but for weeks there was no way of telling how many were living in cellars or hiding in the outskirts. The most significant change in comparison with communities occupied earlier was a great increase in Wehrmacht deserters, Volkssturm men, and policemen who had stayed behind in civilian clothes. According to a strong rumor, a hundred Gestapo agents, called "die raechende Schar" (the avenging band) , had also stayed, to kill anyone who collaborated. If the rumor was true, the agents must have put caution before vengeance, because they were never heard from.

The first Americans into Cologne pronounced their welcome "terrific." They had not seen anything like it in Germany. The days were bright and sunny. Beerhalls and restaurants offered free beer and wine; people on the streets looked at the troops as if they were heroes; and to those who could understand German and to the many who could not the civilians said, "Endlich seid Ihr gekommen. Seit Jahren haben wir auf Euch gewartet." (At last, you have come. We have waited years for you. ) When the weather became dreary two or three days later, the mood appeared to fade, and the Americans decided upon reflection that the joy had been "patently false" anyway.28

Finding the city a wreck and over 70 percent destroyed was no longer a surprise, but the cellar life that had sprung up under the constant threat of air raids continued to astonish the Americans. The average citizen seemed to find spending his life underground entirely normal. A typical cellar contained bedding, a stove, a cabinet, and some decorations to give the place a homey touch. In the cellars, the inhabitants had even developed a brisk trade and social life. Many were hesitant about coming up into the daylight and facing the new risks of the occupation, but most were out in a few days scavenging among the ruins. The military government officers observed, as they had elsewhere, that the first reaction seemed to be to regard all unguarded property as free for the taking.

For E1H2 and its commander, Lt. Col.

[189]

IN THE WAKE OF BATTLE a German woman surveys the wreckage of her property.

R. L. Hyles, the big problem was to rebuild the city administration under 12th Army Group's recent and rigid directive against employing Nazis and without letting a clique like the one in Aachen emerge. The detachment had to do more of the work of running the city, handpicking the officials at all levels, not only at the top, and supervising those who did qualify since, if they were up to the new standard of political purity, the chances were their other qualifications were weak. Hyles' prize appointee was Dr. Konrad Adenauer, who had been Oberbuergermeister of Cologne from 1915 to 1933 when the Nazis forced him out. He had been in jail for several months after the 20 July 1944 attempt to assassinate Hitler and, after his release, was prohibited from returning to Cologne. To wait out what was left of the war, Adenauer had settled in Rhoendorf on the right hank of the Rhine five miles downstream from the Remagen bridge. In his seventieth year, he had done poorly at choosing a refuge from the war but brilliantly in setting the stage for a late political career. When the bridgehead front passed Rhoendorf, military government brought him to Co-

[190]

logne and reinstalled him as Oberbuergermeister, in secret for the first two months because his three sons were in the Wehrmacht.29

Cologne demonstrated on an ominously large scale something that had been observed earlier at Aachen : the helplessness and hopelessness of a city cut off from its lifelines to the outside. The city administration, German and American, could do practically nothing about getting the railroads, the power grid, or the food distribution system functioning again. Fortunately, the breakdowns in these services antedated the occupation, and the civilians had adjusted to them. The cellars contained stocks of food and coal, and the city had seventy-five wood-burning trucks. Electricity came in sporadically over the German grid. When it was on, the civilians could tune in their radios and hear the German stations across the Rhine broadcasting that the new chief of police in Cologne was a "cocky Jew," that the Americans were forcing women to bury the dead dug out of the rubble, and that hundreds of Negroes were standing guard over German civilians and forcing them to clean up the streets.30 The detachment believed that the population benefited by being able at last to compare the Nazi propaganda with reality.

Third Army's 10th Armored Division entered Trier on 1 March, and Detachment F2G2 moved in two days later. Lying close to the West Wall, Trier had been under artillery fire and air bombardment for months. The people, except for about 4,000 of the normal 88,000, had either moved east or gone into hiding. Electricity and water were out. When the detachment, under Lt. Col. S. S. Sparks, arrived they found that most life had settled in the Kemmel Caserne (barracks) on the heights above the city, which was beginning to fill up with displaced persons filtering in from the east. In the first week, Sparks appointed Friedrich Breitenbach as civil leader in Trier-avoiding the more dangerous title of Buergermeister-and registered the population, which by the time the registration was completed had risen to nearly six thousand. As long as the count did not go above ten thousand, the city promised to be in relatively good shape for the time being. People who stayed had stocked up on food in advance, and although the city was 80 to 90 percent destroyed, the housing was adequate. The big problem, as it would be in most heavily bombed cities, was water. The only reliable sources were three Army chlorination tanks and a trickle still running in an ancient Roman aqueduct. When the detachment discovered it could get a little electricity by tapping the German power grid, it began work on getting the big pumps that served the city water system back in operation. The reservoir and the pumps were in good condition, but troubles soon began to multiply. First the electric lines serving the pumps were dead. The trouble was eventually traced to a switch house that an Army photo group had decided to convert into a baggage room. When the pumps were turned on, the leaks began to show. The geysers in the streets were spectacular, but worse were the breaks deep underground which were hard to locate and repair. Restoring the water system would take months. For a while, what was left of the city seemed likely to burn up before the water was

[191]

COBLENZ, MARCH 1945. In the background the forts at Ehrenbreitstein.

turned on. Careless soldiers and roving displaced persons caused so many fires that the army had to send in the 1240th Fire Fighting Platoon to help the local volunteer fire department. The first day without a fire was 29 March which, Sparks noted in his report, was also the first day the displaced persons had not been allowed to leave the Kemmel Caserne.31

The detachments at Cologne and Trier did not have to contend with enemy shellfire or counterattacks. At Coblenz, on the Rhine at the mouth of the Mosel, the situation was different. Lt. Col. M. W. Reed took Detachment F3G2 in behind the assault troops on 20 March. He opened his headquarters in a hospital on the bank of the Mosel near where the assault boats landed and moved to the city hall in the afternoon after it was secured. The inhabitants were even less a problem than at Trier. In the first place there were only about 4,000 people in the city, and few ventured out to bring their complaints or requests for passes to the detachment. Ger-

[192]

MILITARY GOVERNMENT HEADQUARTERS, COBLENZ

man forts on the heights at Ehrenbreitstein across the Rhine kept nearly the whole city under observation, and anything that moved, even individual persons, drew artillery or sniper fire. At night, from the gun platform of Fort Constantine in the city, the detachment could watch one artillery duel going on downstream between First Army and the Germans around the Remagen bridgehead and another closer at hand upstream between Third Army's artillery and the guns at Ehrenbreitstein. Overhead the tracer and mortar fire, accompanied by the thunder of the American howitzers firing farther back, made a permanent fireworks display. On the 25th, a German patrol raided downtown Coblenz and sent some civilians and a smaller US patrol running to the city hall for safety.32

Before the end of March, 150 detachments were deployed in Germany, almost two-thirds of the total EGAD strength. Ninth and Third Armies had committed all the detachments assigned to them, except for some E detachments. Not all of these detachments would be needed perma-

[193]

nently in the Rhineland, but all were busy. H and I detachments were holding areas three and four times the size they had been designed for, and an average small town was getting only about four or five days of actual military government in a month. To help the detachments keep order, among the troops and displaced persons as much as among the Germans, the armies converted field artillery battalions to security guard duty and began authorizing them to appoint Buergermeister and post the proclamations and ordinances.33 The speed of the advance threatened to make ECAD's predicted personnel shortage an imminent reality; and the War Department's temporary overstrength allotment, which reached SHAEF in late February, did not reach EGAD until March. Then the officers and enlisted men still had to be found, trained, and organized into detachments. One modest piece of good luck helped. On 22 February, EGAD opened a school at Romilly Sur Seine to give Air Force and airborne officers two weeks' training in military government liaison. At the end of the first course, nineteen graduates requested transfers into the division, having been advised "without proselytizing or promises" how to go about it. In the second course the school shifted to training both officers assigned to EGAD and EGAD enlisted men nominated for field commissions as second lieutenants under the recent allotment. 34

Shorthanded or not, military government was propelled onto center stage in March 1945. The war would not wait. Training and practice were over and the real occupation was on. The nation that had almost conquered Europe was being brought as low as any of its victims had been. Germany's long-range future, if it had one, was undecided; the immediate future was in the hands of the G-5's and military government detachments, and even they were unsure of what it was to be. For the moment, what they saw most clearly were the approaching shadows of two relentless companions of war, disease and hunger.

The Germans were not starving, yet. In the cities, reduced populations and cellar stocks combined to make the short-term outlook deceptively bright. Searches in the basements of abandoned dwellings regularly turned up small reserves, mostly potatoes and home-canned vegetables. In Germany flour milling was still a local industry, and the mills usually had some unground grain on hand, which could be extended by setting the extraction rate up to 90 percent. Some places had lopsided surpluses. Alzey, in the fertile Rhine plain, had 5,000 excess tons of potatoes but no meat other than horse meat and not much of that. One thing was certain everywhere: the Germans were better off in March 1945 than they were likely to be again any time soon. The Rhineland, like all western Germany, was a food deficit area. Normally, the half of the Rhineland south of the Mosel imported a half million tons of food every day, equivalent to one fifty-car trainload ; but no trains were running, nor was there enough transportation to ensure the movement of local produce. A survey

[194]

showed sufficient livestock to provide half the minimum monthly meat tonnage; enough chickens to supply one egg per person per month, "provided 300,000 people do not like eggs" ; enough milk to give each child under ten a pint a week; and enough butter to provide each consumer with a half pound a month.

The statistics, however, were less chilling than what the detachments had reported during their march to the Rhine. In the countryside, fields were unplowed and practically no one was at work on the farms. The young men were gone ; the registrations showed that 90 percent of the males were over fifty years old. The foreign workers and prisoners of war who had made up the bulk of the agricultural labor force quit and took to the roads as soon as the front passed. There were too few horses. They, like the men, had been drafted into the Wehrmacht. Finally, thousands of acres of land were mined and too dangerous to work.

Famine lurked in the unplowed fields. Military government told the Germans that what they expected to eat during the next winter they would have to raise themselves. For what it was worth, the armies ordered the troops not to use local food, and military government tried to persuade the foreign workers to stay on the farms. In a more practical vein, SHAEF instructed the army groups to restrict the farmers' movements as little as possible. As a result, most units limited the curfew to the hours between sunset and sunrise, and in the Landkreise many allowed free circulation throughout the Kreis during daylight. The speed of the drive to the Rhine brought one unexpected dividend : the retreating Germans did not have time to get all their horses across the river. By the end of the the armies had rounded up several thousand and were turning them over to the farmers.35 Under the pressure of the war and existing policy restrictions, military government could not do more. To provide f or acute emergencies and for the displaced persons, 12th Army Group moved 80,000 tons of relief supplies into Germany during March; by the end of the month Third Army alone had issued over 7,000 long tons of food to displaced persons.36

In cold logic, hunger was the Germans' problem. It could be argued that whatever befell them was their own doing. But the rickettsia microorganism, which causes typhus, did not trouble itself to distinguish between victor and loser. It accompanied war but was not concerned with justice or with causes, any more than was the body louse on which it traveled. On the drive across the Rhineland all the armies discovered cases of typhus. The 6th Army Group found several in a camp for Russian forced laborers near Saarbruecken. Some inmates had wandered off, and, predictably, the disease also began appearing in surrounding DP camps. In Cologne a small epidemic had begun from two separate sources before the Americans arrived. In January, a doctor and several SS guards escorting political prisoners eastward had f alien ill and entered the hospital in Cologne. In the confusion of war and the continuous bombing, they were at the hospital two weeks

[195]

DP BEING DUSTED WITH DDT

before their cases were diagnosed as typhus. By then they had infected several nurses and others on the hospital staff. The second source was the Klingelputz prison where, owing to overcrowding and neglect, the Germans did not detect the disease until after it had passed from the prisoners to the guards and been carried outside the walls. Having seen at first hand what the disease could do, the army and army group G-5's reported that they could not prevent its spread to the troops with the resources they had, and SHAEF issued orders making public health a command responsibility and the concern of all US medical officers in Germany. SHAEF also began shipping in enough vaccine to inoculate all displaced persons. ETOUSA, charged with maintaining the communications zone across France, set up a cordon sanitaire on the Rhine from the Netherlands to the Swiss border and allowed no civilians to cross without an examination and DDT dusting. Persons going west into France were dusted with DDT at the border control stations. At the end of the month authorities were far from certain that the disease was being stopped. Cologne still had 185 suspected cases, and there was no way to isolate carriers among the displaced persons, short of

[196]

a rigid and probably unenforceable stand- fast order.37

Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives

The Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives branch (MFA&A) had not developed even to the modest proportions envisioned in early 1944. SHAEF and 12th Army Group had MFA&A sections in the G-5, and each "E" detachment had space for one MFA&A officer. In the advance in March and April 1945, the armies employed one officer apiece on detached service from the E detachments.38 On the other hand, the monuments multiplied as the front moved into Germany. The monuments, including archives, in the SHAEF official list totaled 1,055 for all Germany. By late March, 12th Army Group had identified 600 in the path of its advance alone. SHAEF had listed 15 monuments in Aachen. After the city was captured, the number rose to 66. The list made no provision at all for art collections, libraries, and archives evacuated from the cities and deposited in remote places to keep them safe during the bombing; and 12th Army Group had found or knew about 115 items in this category before the end of March.39

Because of the nature of the war, even having many more MFA&A officers could not have prevented the most extensive losses. The bombs had generally done their work days, weeks, or months before the first Americans appeared on the scene, and MFA&A had left to itself the sad task of assessing what had survived and what was gone for good. In the old city of Trier, for instance, the only structures found undamaged were the Roman ruins. The bombers had obviously tried to avoid the churches but were only partially successful. The cathedral, the oldest Romanesque church in Germany, had taken one direct hit, and the bell had shaken loose and fallen through the tower. The Liebfrauenkirche, an early Gothic structure dating from the thirteenth century, was badly damaged, and the eighteenth century Paulinuskirche had a hole in its roof. In both structures, all the windows were blown out. The most that could be done was to make the buildings weather-tight to prevent added damage from the elements. In buildings so old, whatever was left was valuable, and close inspection revealed that some things, such as the paintings in the interior pillars of the Liebfrauenkirche, had survived practically intact.40

Muenster, fifty miles east of the Rhine, was the only city in Ninth Army's path on the first leg of its march across the north German plain. It was bombed and burned on Sunday, 25 March 1945. Capt. Louis B. LaFarge, Ninth Army MFA&A officer, wrote its epitaph:

The greater part of the old city of Muenster is gone for good. It is little better than rubble with the towers of the medieval churches alone standing to mark what the city once was. All the fine fourteenth to eighteenth century buildings are gone. The cathedral sustained direct hits on the western porch and the nave, and an unexploded bomb lies near the sacristy door. The nave is roofless, and much of the north wall is gone. The south face remains standing and

[197]

is surprisingly untouched. The towers have lost their roofs. The more precious moveable property is bricked up in the bottom story of the towers. The approaches to both towers are so covered with rubble that the treasures are as safe as they can be. There is little that can be done at present. The Domprobst [prior] responsible for the treasure is dead, and a new one has not been appointed. The architect is old, ill, absent, and useless; and a new appointment must be made. The bishop and the vicar general have migrated to the village of Sendenhorst, and the only resident canon who had concern in the matter is an old man of somewhat defeatist views.41

Probably the least necessary casualties were the castles, of which the Rhineland had a large number. Most, generally located in isolated spots, had come through the bombing well; but castles have military associations, and sometimes the artillery could not resist laying in a few rounds. Castles also were rumored to have fabulous wine cellars, which made them magnets for thirsty troops. They also made attractive command posts and billets, often the only ones for miles around. Unfortunately, because they were generally safe from bombing, the Germans had done nothing to protect the castles or their contents and had used them to store art work and archives evacuated from the cities. From experience, MFA&A officers ranked them as the least safe depositories, after ordinary country houses and far below churches, monasteries, and hospitals. After the experiences at Rimburg Castle and a castle of the Deutschorden at Siersdorf near Aachen, where a division had set up its command post and moved valuable carved panelling from the Aachen Rathaus (city hall) out into the weather, units had been ordered to inventory all valuables and store them under lock and key; but such orders were notoriously hard to enforce in a fluid situation.42

One castle which had not escaped the air raids was the Schloss Augustusburg, located in Bruehl. Augustusburg had been a fine example of baroque architecture, complete with a grand staircase, chapel, gardens, and outlying lodge. On 10 October 1944, a single bomb destroyed the north wing. On 28 December, several bombs had hit near the chapel, and the concussions smashed the plaster baroque and rococo interior. On 4 March, two days before the castle fell into American hands, three artillery shells struck the main building. Testimony taken later indicated that no German troops had been in or near the building. One shell blew a corner off the roof. The other two detonated inside and did extensive damage. Before the military government detachment arrived in Bruehl, troops bivouacked in the Schloss and caused more damage. Again it was a case of trying to salvage something from the wreckage. Detachment I1D2 found an architect, a master carpenter, and a dozen carpenters and laborers and put them to work patching the roof, shoring up the walls, and putting cardboard in the windows. Material had to be scavenged from other ruins in the city. The detachment stationed two German policemen on the grounds, but they had no authority over US soldiers who continued to go in and out as they pleased.43 Augustusburg seemed likely to suffer the same treatment as Rimburg. Ninth Army G-5 had inspected Rim-

[198]

MFA&A POSTS ROOM IN WHICH MUSEUM PIECES ARE STORED

burg Castle again in late February and found the furniture and art work scattered about, some thrown into the moat, and the locked rooms broken into and rifled.44

Lt. Col. Webb, SHAEF's MFA&A adviser, toured the two British armies and US Ninth Army in March. Pillage and wanton destruction, he concluded, were at least a combined effort, being as prevalent among the British and Canadians as among the Americans. At juelich, he saw slashed pictures and cases of books from the Aachen library broken open and their contents strewn about by souvenir hunters. Aware that the prevailing mood was not one of kindliness toward Germans or their property, he pointed out that the German collections also contained looted art work which the Allies had pledged to restore to their rightful owners, and these pieces too were threatened. SHAEF G-5 forwarded Webb's report, adding, "It is appreciated that a certain amount of `toughness' may be desirable in occupied territory and it is not suggested that we should instruct our troops to act in Germany as they have usually in liberated territory; nevertheless, it

[199]

is important that Allied troops should not desecrate churches and should not destroy works of art looted from our allies." 45 It was, in fact, not a good time to attempt to convert the troops into guardians of German culture. General Smith passed the Webb report on to the army groups with the slightly equivocal comment that looting had to be considered a less despicable offense on enemy territory than on liberated territory but ought to be discouraged for the sake of the restitution policy and "to impress on the inhabitants the fact that their conquerors are superior to them not only in military prowess but in their moral standards." 46

In January 1945, the twenty-nine Poles in the camp at Brand were the only displaced persons held by SHAEF in Germany. On 31 March, the army groups reported 145,000 on hand in centers and 45,000 shipped out to France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg, the latter mostly repatriated citizens of these countries but also including eastern Europeans. Many thousands more had not reported to the centers or had not yet been evacuated from the division areas. The number of DPs on hand had doubled in the last week of the month and, wherever the Rhine was crossed, multiplied with every mile that the front moved east. By the time the Remagen bridgehead attained an area of fifteen square miles, it contained 3,500 DPs, 235 for every square mile taken.

The intelligence reports of the previous fall had been correct. The Germans had moved many forced laborers out of the Rhineland. The number of persons recovered, therefore, was less than half the total that had been there as late as September 1944, which was lucky, since the DP problem even with those who were left was bigger than had been anticipated. Nobody was hugely surprised when the DPs ignored SHAEF's appeals to stand fast. The DPX, however, had expected those on farms, where lodging and food were assured, to stay at least several weeks; they had not. Like the others, they had taken to the roads as soon as they knew they were liberated. On bicycles, on wagons, and on foot, displaced persons streamed away from the rural districts at the same time others were leaving towns and cities-many, the Russians and Poles especially, heading no place in particular other than away from where they had been. Cut loose from the German economy and unable to provide for themselves, they became the charges of the first U.S. unit they met. In a fairly typical instance, the 5th Infantry Division, on one day, 27 March, found 190 DPs in three towns in its sector, 400 more on the roads behind the front, and another 300 in the area uncovered in the day's advance-together, enough to fill a good-size camp. Assembly centers run by the armies quickly reached populations of 10,000 or more. Western Europeans could be kept moving toward home, but on 12 March SHAEF closed the border to the Poles, Russians, and other eastern Europeans for fear of wrecking the already weak French economy. The eastern Europeans, who made up more than half of all the DPs, hereafter became an unanticipated long-term respon-

[200]

RUSSIAN DPS PREPARE MEAL IN CAMP AT TRIER

sibility of the occupation forces. Unanticipated too was the amount of care and supervision they needed. Homeless, without jobs, knowing neither English nor German, elated at being free but uncertain about the future, sometimes restless, sometimes apathetic, they caused problems in more than just feeding, housing, and road-clearing, as the DPX sadly discovered. SHAEF had proposed to turn the DPs over to UNRRA teams, but in March only seven teams appeared. The H and I detachments did the work; they were sometimes reorganized with a doctor, US or French welfare workers, and Allied liaison officers attached, and often operated without assistance and as a sideline to their military government assignments.

The two largest DP assembly centers established during the Rhineland campaign were at Brand, outside Aachen, and at Trier. Both were in former German army barracks. The Brand camp, after being used in the fall of 1944 for German refugees, had later been used as a hospital. Kemmel Caserne, outside Trier, had been a German Stalag (prisoner of war camp) . It had no water supply, and when First Army surveyed it on 7 March it was pronounced too foul for anything but emer-

[201]

gency use; by then, however, the DPs were arriving by the hundreds and there was no other place to put them. Some came on foot; most were brought back by supply trucks returning from the front. Within days Brand reached a population of 15,000, Trier 12,000. The Belgians, Dutch, and French could be sent across the border toward home as fast as they arrived, and 700 to 1,000 a day were processed through the camps. After SHAEF closed the border to eastern Europeans, the Russians and the Poles became permanent inmates. Maj. Melvin B. Vorhees, who was with F 1 G2 in Aachen, remembered them vividly when he wrote the detachment's report a year later:

In Aachen there were thousands of Russian DPs . . . . They lived in a huge

caserne, and it must be said they were filthy in the highest degree. They ruined

the light wires every time they were installed; telephones were ripped out;

windows were broken as soon as they were installed ; fires broke out

"accidentally" ; a liaison officer was murdered ; and the camp was in a constant

state of chaos. The tactical troops assumed "responsibility" for the camp. They

issued passes every afternoon for a group of DPs to visit the town. The visits

were looting expeditions. The DPs would leave the camp with empty baskets and

briefcases and return at nightfall loaded down like camels with all manner of

goods.

Murders, rapes, and robberies abounded. Several Russians were put in prison,

but they caused so much trouble they had to be turned over to the penitentiary

in Ebrach. Everything was run on a hands-off kidglove policy, which was not

conducive to discipline.47

Third Army began phasing out the camp at Trier after it captured Baumholder, which had once accommodated 50,000 German troops, and other Casernes in the Mosel and Rhine valleys. S. Sgt. C. M. Tipograph saw the camp at the height of the campaign before better accommodations were found:

The Camp

High on a hill overlooking the blighted city of Trier, the camp consists of a

number of bleak greystone barracks disposed around a parade ground. At a

distance the buildings still seem to retain some of their former military

primness and neatness. However, on closer inspection they present a spectacle of

confusion and human degradation which is difficult to describe.

Literally thousands of former German slaves of all nationalities are

constantly arriving or departing. The camp is administered only by three

officers and six enlisted men, aided by two female members of the French Army.

Sanitary Conditions

Appalling. As soon as I arrived I became unpleasantly aware of the stench of

human excrement. I myself witnessed occupants of the camp who in plain view

were defecating in the shrubbery in their barracks. No facilities for bathing

or washing existed except for water hauled in containers from nearby tanks and

pumps. The interiors of the buildings, except one-where French PWs are housed-are

indescribably filthy and disorderly; all sorts of litter from broken bottles

to articles of clothing lie strewn about on the floor. The occupants live in

extremely crowded and unsanitary conditions and there exists a grave danger

of disease of epidemic proportions-a danger not only for them, but also for

American troops in the city where the occupants are allowed to circulate.

The occupants for the most part have no change of clothing and pitiably few

other belongings. I assume from the fact that many of them continually scratched

themselves that the existence of body lice is widespread.

It must be admitted that the DPs themselves do little or nothing to alleviate

their own miserable situation. With a bit of initiative and organization, having

plenty of time, they could easily tidy up the place. Yet, just this spark of

initiative and organization seems to be lacking. It must be recognized that the

[202]

camp is only a very temporary makeshift stopping place, with which none of the occupants identifies himself, each hoping to be off on his way home in a day or so. Even so, the sanitary conditions are such that they could only be tolerated by people who have lost their sensitivity for the niceties of civilization and have had their powers of self-reliance undermined.

The Russians

The Russians seem to have suffered the worst degradation of all the DPs in the camp. They apparently are often drunk in the daytime as well as at night, and they are not above vomiting on the passageways or in the sleeping quarters. They loll around in the sun, conduct love affairs, or go down the hill and wander through the city, of which they have free run. They take delight in pillaging or destroying German property. I saw one Uzbek in the town who was systematically slashing an upholstered sofa. When I asked him, in my halting Russian, why he was doing it, he smiled and said, "Nyemitsky (German)," and continued industriously at his work.48

SHAEF's policy was to guarantee the DPs and RAMPS (recovered Allied military personnel) , the latter in the Rhineland mostly French and Russian prisoners of war, adequate food, shelter, and medical care-at the Germans' expense to the maximum extent, and out of Army resources whenever necessary. Military barracks provided the most efficient housing, but where there were no barracks, military government requisitioned hotels, schools, factory buildings, or private homes. At a small place called Lauterecken in the Third Army area, the Buergermeister failed to arrange space for DPs its ordered. One night a truckload of thirty-five arrived, and military government moved them in with him.49 The DPs received 2,000 calories subsistence per day; the RAMPs received a U.S. private's ration, 3,600 calories. Local German officials were told how much food was needed and that if they did not provide it, military government would step in and take what was needed from stores, warehouses, or any place else it could be found. The Germans got what was left, on the average about 1,100 calories. The camp at Brand used 300,000 rations in its first ten days, consisting of two-and-one-half tons of vegetables obtained from the Germans locally and captured Wehrmacht stocks trucked in from a depot at Liege. The two meals a day each took four hours to serve. Two smaller camps at Duisdorf issued a quarter million rations in March, and six thousand blankets and eight tons of Red Cross clothing.50 At Krefeld, a military government private, first class, Irving Stern, ran a camp for 3,000 DPs in a prison. To feed them he supplied flour to the Krefeld bakers and made them hake bread and secured coffee from the troops, milk for children from farms, meat from German warehouses, and potatoes and barrels of sauerkraut from the prison cellar.51 Possibly the most elegantly appointed camp was at anrath in the Ninth Army area. It was situated in a large former prison and supervised by an I detachment and a sanitary collecting company. The 3,000 DPs were fed from captured stocks that included butter, honey-butter, flour, rice, prunes, macaroni, spaghetti, meat, ersatz coffee, cocoa, sugar, soup stock, and dried vegetables. The prison farm a short distance away sup-

[203]

plied potatoes and milk. A bed factory delivered mattresses, and in a crockery factory, the detachment turned up enough cups, bowls, and plates to feed 20,000 persons.52

The care and feeding of the Russians was carried out from the beginning-as it would be to the end-to the accompaniment of nightmarish political overtones. Before D-day, knowing that the Germans had recruited captured Russians into collaborator military units, SHAEF had asked the Soviet government what it wanted done with its nationals captured in German uniform. Moscow had blandly replied that the problem would not arise because there were no such persons. In France, the armies had begun picking up Russians serving with German units, but it was October 1944 before the Soviet Military Mission at SHAEF admitted their existence.53 Having made the admission, it demanded that the Russians no longer be regarded as prisoners of war and be segregated and accorded special status as "liberated Soviet citizens." When SHAEF complied, the Soviet desires concerning ration scales, pay and privileges, and working conditions became progressively more exacting, culminating after the turn of the year in a demand that Soviet civilians, of whom some thousands were in SHAEF's hands, be given identical treatment with the prisoners of war. In the meantime, owing to constant Soviet interference, discipline had become almost impossible to maintain among the "liberated Soviet citizens," and in January SHAEF asked the War Department to assign two 3,000-space troopships to take the Russians home.54 But they were not going to be disposed of that easily. On a closer look, the SHAEF Provost Marshal concluded that the United States did not have a right under the Geneva Convention to transfer Russians captured in German uniform to Soviet custody. Under the convention, the uniform, not a man's actual nationality, determined his right to prisoner of war status; consequently, if any of the Russians were later killed or mistreated, the United States could be held responsible and its troops subjected to German reprisals. That the Russians would not be given such preferential treatment at home as their government demanded for them from SHAEF was readily deducible from a recent British experience. The British had repatriated about 10,000 Russians captured in the Mediterranean theater and had seen them marched away under heavy guard as soon as they landed on Soviet soil.55

By early February, when the Big Three met at Yalta, the Soviet armies had overrun camps holding Western prisoners of war, including Americans and British, in Poland and eastern Germany. The main objective of the American and British negotiators thus became to secure good care and a safe and speedy return for their own men. The chief Soviet interest was to get all of its citizens back whether they wanted to return

[204]

or not. The Soviet negotiators demanded that all their nationals-those captured in German uniform, liberated prisoners of war, and civilian DPs alike-be regarded as forming a single group of "liberated Soviet citizens" for repatriation and for treatment while under SHAEF's control. In a protocol signed on 11 February the Russians had their way : they would get back all their citizens in a trade for a much smaller number of Western prisoners of war liberated by them. The meaning of the article on repatriation did not have to be faced right away but the meaning of the article on treatment did. Strictly interpreted, the article appeared to entitle former Soviet military personnel, either prisoners of war or those captured in German uniform, to treatment equal to that given US troops of the same rank and entitled Soviet DPs to at least the standard of living of US privates.56

Since SHAEF was already practically committed to giving the former Soviet military personnel treatment comparable to its own troops, the most remarkable feature of this aspect of the agreement was the provision linking the Soviet DPs to the scale for privates which, SHAEF told the Combined Chiefs of Staff, would impose impossible supply requirements. In terms of food alone, raising the rations for an estimated 1.4 million Soviet DPs from the planned 2,000 calories to the 3,600 calories of a US private would require an additional 110,000 long tons of supplies. Furthermore, to raise the ration for Russians and not for other DPs would be administratively difficult and politically dangerous; but to guarantee all DPs 3,600 calories would require at least half a million additional tons of supplies.57 As it was, SHAEF was having trouble getting shipping for the supply commitments it had and was not certain it could maintain a 2,000-calorie scale for DPs.58 The DP ration stayed at 2,000 calories, which appeared to be consonant with the protocol after SHAEF decided that the sense of the agreement had been to provide for adequate food, clothing, housing, and medical treatment not to establish a fixed standard.59

SHAEF conceded that the DPs had a special claim on SHAEF resources and, as the most numerous and obvious victims of Nazi exploitation, on German resources as well. They were to be among the first to witness the dawning new age promised in the Atlantic Charter. In the plans the DPs were a convenient abstraction ; dealing with them in the flesh, however, quickly proved to be an altogether unanticipated experience. For one thing, the designation "DP" turned out to be almost synonymous with "Russian" (with an admixture of Poles and other eastern Europeans) . They were the majority, the real slave laborers, the ones most in need of care, and the most

[205]

exasperating to care for. PWD investigators sent out during the campaign pronounced them "astonishingly well-behaved" and dismissed German complaints of looting and unruly behavior as "a mixture of hypocrisy, impudence, and subtle propaganda." 60 The military government detachments dealt with them more intimately, and their judgments uniformly ran along the lines cited earlier from Brand and Trier and the following from a camp for Russians at Neustadt:

Lacking direction the majority of these DPs live voluntarily in the dirtiest conditions imaginable, and it is difficult to induce them to clean their quarters. In the camp at Neustadt a "mayor" and a "police force" were appointed and the "mayor" was instructed to have the place cleaned up before they were fed. Looting of wine cellars and the resulting drunken orgies have created trouble . . . . Heated arguments and loss of tempers have caused two murders to be committed here. The bodies were thrown out of the building, and it was only after specific orders were given that they were buried. It is impossible to find out which Russians killed the others.61

The dawn of the bright new world was clearly not going to be serene.

In the third week of the campaign SHAEF G-5 Forward canvassed 12th Army Group and its armies and concluded, "The strictly tactical theory of military government has broken down of its own weight under pressure of practical considerations . . . ." The armies, the intended chief beneficiaries of the tactical system, conceded that an area as large as the Rhineland could not be administered for long within arbitrary unit boundaries, which sometimes divided cities in two, as the First Army-Ninth Army boundary did at Aachen. The detachments were being showered with regulations by tactical commands above them and could find themselves simultaneously taking orders from platoon commanders and army headquarters or any staff in between. One I detachment was under two corps and three divisions within five days. However, some functions, mainly agriculture and food distribution, were too broad for the armies to control. The 12th Army Group was having to take a hand in co-ordinating the armies' operations, and SHAEF G-5 expected the early result to be a compromise between the tactical and territorial systems, probably to lie achieved by installing the regional E detachments.62 At the end of the month, however, after the front had moved across the Rhine, the compromise was achieved without abandoning the principle of tactical control. Headquarters, Fifteenth Army, which SHAEF had been using for odd jobs, moved in to set up a blocking line on the river and assumed territorial G-5 responsibility for the Rhineland.

The field survey also found a deficiency in political guidance which it predicted could have "calamitous results in the not too distant future." All military government activities had political implications, lout the guidance from the top was so meager that policy development-such as it was-was being left to the detachments in the field. The SHAEF policy so far was all negative: to destroy nazism and milita-

[206]

rism. Nothing had been decided about what to put in the place of nazism: yet, just by appointing people, military government was creating a political complexion. Without guidance, the detachments were following their own political likes and dislikes or relying on the German clergy, which meant that in the Rhineland the political outlook of the Catholic Church was becoming predominant. 63

[207]

Return to the Table of Contents