CHAPTER XXII

The Turning Point

Military Government in the Static Phase

After the carpet was taken up, the area in Germany remaining under U.S. military government control was about the size of the state of Kentucky but with five times the population.1 The withdrawal into the zone had reduced the US -administered area by more than two-thirds and the number of people by at least as much; however, the consolidation and additions of new personnel raised military government strengths at all levels. Between August and October 1945, although they were already under the shadow of redeployment, the detachments experienced a personnel explosion. The Land detachment for Bavaria went from a hundred officers and men (in May) to nearly five hundred. Detachment E2C2, which had taken over Hesse-Nassau in July with 35 officers and 36 enlisted men, had 94 officers and 134 enlisted men in September. A typical Land and Stadtkreis detachment, 17E3 at Ingolstadt, Bavaria, started out with 3 officers and 5 men and in September reached a strength of 10 officers and 30 men.

Although the planning at least as far back as the Standard Policy and Procedure in early 1944 had envisioned indirect control through German agencies, military government was still functionally locked in at all administrative levels. The stage when the detachments would supervise rather than operate seemed no closer than it had when Captain Goetcheus and I4G2 ran Monschau as an island between the German and American front lines. The main difference was that the number of functions and the scope of responsibilities had increased. When the Production Control Agency went out of existence in August 1945, its entire array of concerns passed from G-4 to G-5 and was shifted to military government down the line. Seventh Army G-5, for example, reorganized into two main branches, Economics and Industry and Internal Affairs. Economics and Industry was further subdivided into two sections: the Economics section (with subsections for labor; transportation; supply, food and agriculture; and trade and industry) and the industry section (with subsections for requirements and allocations; reports and statistics; oil; public utilities; building materials; construction; housing; forestry; and industrial control, which was further subdivided into machinery and equipment, metals, electrical equipment and instruments, chemicals, consumer goods, and coal and nonmetallic mines). Internal Affairs had ten subsections: civil government; public safety; posts, telephone, and telegraph; education and religious affairs; legal and prisons; finance

[396]

and property control; displaced persons, refugees, and liaison; public welfare; public health; and monuments, fine arts, and archives.2 Not all upper echelon functions were also functions of the Kreis detachments; but the Kreis detachments bore almost the entire burden of denazification and property control, which they could neither pass upward nor delegate to the Germans. The detachments were also experiencing no decline in the military government court cases. Black marketeering, DP crimes, and Fragebogen falsifications more than outbalanced a tapering off of circulation and curfew cases. By November, the military government courts in Munich had a backlog of 26,000 cases. Nearly all of the detachments were providing some direct services. In Munich, the detachment's public utilities experts, Maj. Elmer W. Price and Capt. Louis Wask, restored the city's gas service, which had been out since July 1944 when a bombing raid damaged the gas works and cracked the mains. Between May and August, using horse-drawn cars at first, they also put the streetcar system into good enough shape to transport 400,000 people a day.3 In Bremen, the detachment's officers in charge of fisheries sent the first two trawlers out on 19 July with dust coal in their bunkers (which gave them a top speed of six knots, two knots less than the speed of an average fish). Two months later, twenty-one trawlers were operating out of Wesermuende with good coal and twenty-nine more were being reconditioned.4

Among the busiest men of the occupation were the MFA&A officers. The art treasures required painstaking care, and the monuments above ground had to be protected against weather damage, theft, and vandalism. In Nuremberg, Detachment B-211 used discharged Nazis who had artistic knowledge to sort through the rubble for fragments of old stone and iron work. The regulations against Germans having weapons or holding foreign currency posed a constant threat-from overly zealous or acquisitive U.S. troops--to antique arms and armor and to coin collections. New finds were still being made. Underground vaults in Nuremberg uncovered during the summer held the Neptune Fountain, which the Wehrmacht had looted from the grounds of the imperial palace in Leningrad, and the great fifteenth century Viet Stoss altar from St. Mary's Church in Cracow, Poland. Two months of detective work brought to light, buried behind two-foot-thick concrete walls and encased in airtight copper containers, the crown, the orb, the scepter, and the two swords of the Holy Roman Empire. Two Nuremberg city officials who had stubbornly lied that SS troops had taken the imperial regalia out of the city in April 1945 received 25,000 mark fines and five-year prison sentences. By late summer, inquiries were coming in from experts and societies all over the world concerning the welfare and whereabouts of libraries and collections, the state of various castles and buildings, and in one instance, the condition of a unique specimen of an Indian shark preserved in a museum in Stuttgart.

The immense task of restoring looted treasures to their proper owners began in September when Seventh Army's special MFA&A team at the Heilbronn salt mines brought to the surface and turned over to

[397]

French representatives the stained glass windows from the Strassbourg Cathedral. Thereafter, freight-car loads of books, art objects, and museum pieces were moved out of the mines, sometimes directly to their owners in France, Belgium, Holland, or Italy but more often to collecting points in Munich and Wiesbaden where they were photographed and identified before being returned to their owners. A special collecting point at Offenbach handled Jewish archives, books, and religious objects. Some two hundred of the most valuable German paintings were shipped to Washington in November for safekeeping, but they and all other German-owned works would be restored to their owners when they could be adequately housed.5 A noteworthy example was the Stuppach Madonna by Mathias Gruenwald, a small work worth two million dollars, which MFA&A found in the Heilbronn mines and returned to its owner, a village parish church in Bavaria.6

Black marketeering and currency manipulation, no doubt, tempted military government personnel as much as the occupation troops, and military government had some temptations that ordinary soldiers did not. There is no reason to believe that the degree of resistance in military government ranks was markedly higher than in the US forces at large, but instances of such complete capitulation as in the following account were rare. When Capt. Norman W. Boring and Lt. Arnold J. Lapiner became the military government officer and deputy in Landkreis Laufen, Bavaria, in early 1946, they were flooded with claims for requisitioned jewelry, cameras, silverware, and radios, none of which could be traced since the detachment until then had kept practically no records of any kind. Among the detachment's civilian employees were typists who could not type and interpreters who knew no English. The detachment had been popularly known as the American Gestapo. In the monthly reports, the denazification sections were blank. An enlisted man in the detachment had held up the local post office for 35,000 marks. When asked why the theft had not been reported, the postmaster said the soldier had threatened to have him thrown in jail if he did and the general behavior of the detachment was such that he believed the threat.7

The detachments attempting to do their work conscientiously had, not surprisingly, various complaints, among which they unanimously agreed on two. One was the seemingly insatiable appetite of the upper echelons for reports. Every new development, such as the licensing of political parties and Law No. 8 added requirements for monthly, biweekly, and special reports. An average Landkreis detachment submitted 109 regular reports during the month of October 1945 and dispatched a total of 305 communications, or, as one detachment figured, 1.3 communications an hour, eight hours a day including Sundays.8 More important, because it affected the detachments' image of themselves and their

[398]

LOADING VEIT STOSS ALTAR for return to Poland.

prestige in the eyes of the Germans, was the not unfounded belief that they were the last ones to know about important decisions. Although not always, as some military government officers contended, but certainly too often, the Germans heard the news on the radio before the detachments received any official word; Law No. 8 was probably the most egregious instance. A good part of the trouble lay in the split between information control and military government. ICD received its information at USFET and, not having to co-ordinate with military government, could have it on the air almost immediately. The same information going to the detachments had to pass through several intermediate headquarters, sometimes being revised along the way.9 The existence of an essentially military government information agency that was separate from military government proved by the fall of 1945 to be a sufficiently glaring organizational weakness to become the subject of a report to the Presi-

[399]

dent.10 However, the most embarrassing episodes, the announcement of Law No. 8 and the licensing of political parties, probably owed less to organizational lapses than to high-level efforts to exploit policies for publicity before they were ready to be put into effect.

Typically, military government did not lack critics in the summer and fall of 1945. The New Republic viewed the Schaeffer affair as demonstrating "the inability of the Army to run the civil affairs of an occupied country." 11 Raymond Daniell of the New York Times charged the officers responsible for denazification with having lost sight of the reasons for which the war was fought.12 The Harrison report maintained that military government officers were timid about inconveniencing the Germans and more interested in getting German communities working soundly again than in caring for the DPs; furthermore, Truman told Eisenhower that the proper policies were not being carried out "by some of your officers in the field." 13 In October, during the aftermath of the Patton and Schaeffer incidents, the Army was completely on the defensive. Eisenhower wrote to Marshall about the "growing storm of discontent, even anger, among columnists and editors" that was giving the Army "a bad name when it is doing an overall good job." 14 Truscott talked to reporters about their "questioning the ability of the military mind to conduct civil affairs in occupied territory"; and Smith declared himself convinced that "the American people will never take kindly to the idea of government exercised by military officers." 15

In trouble with the press and publicly rebuked by the President (the White House released the President's letter to Eisenhower and the Harrison report on 31 August), military government's future was indeed murky-and that of the German people even more so. The important question of whether the Army was adequately performing its mission in Germany was being answered emotionally; and the more important question, in human terms, of what was going to happen to millions of Germans, both good and bad, was in danger of not being considered at all. Fortunately, on the day before he released the Harrison report, the President had sent Byron Price, who had been the Director of Censorship and who was an experienced newspaper man and former executive editor of the Associated Press, to Europe to "survey the general subject of relations between the American Forces of Occupation and the German people." After ten weeks in Germany, Price submitted a summary of what the occupation had done and not done since the surrender and a review of the problems ahead: hunger, economic reconstruction, and democratization. Concerning what had been done so far he concluded:

Taken altogether it [military government] seems to me a notable record of progress, whatever may be said by noisy backseat drivers. No one who knows the facts can fail to give General Eisenhower, his Deputy General Clay, and the staff of Military Government generally his continuing confidence and commendation. In no other zone of Germany

[400]

has greater progress been made toward the declared objectives of the Allied occupation.

As to the future, he warned, "The United States must decide whether we mean to finish the job competently, and provide the tools, the determination and the funds requisite to that purpose, or withdraw." 16 On 28 November, the President released Price's report to the press together with a letter to the Secretaries of State, War, and the Navy in which he directed them to "give careful consideration to this report, with a view to taking whatever joint action may be indicated." 17

At his first meeting with the Army commanders on 21 June 1945, Clay told them that the War Department believed military government was "not a job for soldiers" and should, therefore, be "turned over to the political as soon as practicable." 18 President Truman had said, more than a month before, that he wanted control in Germany shifted to civilian hands as quickly as possible because he believed it was in the American tradition "that the military should not have governmental responsibilities beyond the requirements of military operations." 19 The President said he wanted the transfer made "as soon as the rough and tumble is over in Germany." Apparently he and Eisenhower felt that time was growing short when they met at Eisenhower's headquarters in Frankfurt in late July and agreed that Eisenhower should organize the military government in Germany so as to facilitate turning it over to civilian authority "at the earliest moment." 20

The idea of organizing military government for a changeover to civilian control was of course not a new one. From the beginning the US Group Control Council had been considered more a vehicle for future civilian authority than an element of Army-administered military government. In April 1945, in his first outline for military government organization, Clay proposed also to bring civilians into the theater G-5 so that both it and the US Group Control Council could be "carved out of" the military command when the shift to civilian responsibility occurred. 21 A month later, in the organizational directive for military government, Clay stated, "This organization must become civilian in character as rapidly as consistent with efficient performance so that it may become at the earliest possible date a framework for the administration of political control in Germany by the appropriate US civil agencies. 22 He told the army commanders at the 22 June meeting that he was "infiltrating highly qualified civilians" into the US Group Control Council and the theater G-5 ; writing to McCloy three days later, he said he understood the creation of a supervisory body for Germany composed of civilians "to be my mission." 23

Until the war ended in the Pacific, the

[401]

numbers of military personnel available for military government assignments made civilianization below the top levels of the US Group Control Council and USFET SGS G-5 an unnecessary luxury. Even in the US Group Control Council, where the number of civilians increased from 83 on 1 May to 326 on 1 September, the relative progress in civilianization was slight since the numbers of officers and enlisted men went from 417 to 1,424 and from 553 to 4,012. 24 In the next two months, however, redeployment altered the proportions rapidly, and the military strength dropped by nearly 2,000 men while the civilians increased to 429. In the first week of September, Clay announced a program to induce officers in particular to convert to civilian status in Germany. On 1 October he initiated a civil service analysis of all military government jobs; and Eisenhower ordered the army commands not to "place any obstacles in the way of these people." 25

The power struggle between the theater G-5 and the US Group Control Council ended in June on Clay's terms. He and General Adcock, the theater G-5, agreed to integrate their staffs; the staff divisions would be located either in Frankfurt or Berlin depending on where they would be most effective. Adcock became in effect Clay's deputy. Clay indicated to McCloy on 25 June that he contemplated as the next step combining the two staffs into a single office of military government.26 Since the merger would remove the top military government echelon from the tactical command channels, it would logically do the same with military government down the line and would constitute a piece of radical surgery on a not entirely willing patient. The USFET and military district G-5's, having no functions that were not duplicated either in the US Group Control Council or the Land detachments, would suffer most.

In mid-September, Clay made a choice between two directives: one would have immediately designated the US Group Control Council as the military government authority and removed the G-5's from the chain of command; the other, which Clay approved, cut as deep but not as fast. As of 1 October, the US Group Control Council became the Office of Military Government (US) (OMGUS) and USFET G-5 became the Office of Military Government (US Zone). The Land detachments became offices of military government for their Laender-Third Army G-5 merging with the Bavarian Land detachment to form the Office of Military Government, Bavaria-and Seventh Army G-5 became the Office of Military Government (Western District ).27 For USFET and the armies, however, and thus for the tactical concept of military government, the end was in sight. Other directives issued later in September and the first week of October ordered the armies to cease all military government activity after 31 December. USFET G-5, as the Office of Military Government (US Zone), became the rear echelon of OMGUS upon notice that its functions and personnel would be gradually

[403]

shifted from Frankfurt to the OMGUS headquarters in Berlin. Ironically, by then, since the Control Council had failed to establish even the most rudimentary German central authority, Frankfurt was a much better site for the zone military government headquarters than Berlin; however, having the headquarters in Frankfurt would have necessitated either withdrawing most of the personnel from Berlin, thus seeming to accept the division of Germany as permanent, or maintaining a large staff in Berlin without anything to do.28

The day after he approved the directive establishing OMGUS and the other offices of military government, Clay wrote to McCloy that the object was to convert military government to a civilian operation and separate it from the military forces as soon as possible.29 On 1 October, Eisenhower told the army commanders "The Army must be prepared to be divorced from military government responsibilities on twenty-four hours' notice." 30 Clay did not anticipate quite so much speed; and when he read the preliminary draft of Byron Price's report to the President, which recommended as did the final report, complete civilianization and the appointment of a civilian high commissioner, he pointed out that the other three Allied governments would have to be consulted and that the complete conversion would probably take until 1 July 1946.31 No doubt, however, considering the official and press criticism, the Army would have liked to get out sooner. Smith directly expressed this view when he told Price that he frankly doubted whether civilians could do a better job than the military, but "from a purely selfish point of view, the sooner the Army is out of this very controversial job the better it will be for the military service." 32

In Washington on 23 October, Secretary of War Patterson and Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal met with Secretary of State James F. Byrnes.33 The subject was civilian control in Germany, which Patterson said he believed should be a State Department responsibility. They agreed that the shift, when it was made, should be to a single department; but Byrnes thought the Army had the best organization and that "it would be a great mistake to make the change now." If the State Department had to take over, he suggested postponing the "bad news" for eight or nine months.34 Three days later in a letter to Truman, Eisenhower reminded the President of their conversion in July and, pointing out that the four occupying powers would have to agree, proposed making the transfer to civilian control no later than 1 June 1946.35 On the 31st, the President released Eisenhower's letter to the press and announced that the shift from military to State Department civilian control in Germany would be made by 1 June 1946. 36

"We Don't Want the Low Level Job"

Expecting in mid-September to have to reduce military government in the field from its peak strength of close to 13,000 officers and men to around 4,000 by early 1946, Clay directed Adcock and USFET G-5 to work out a means of reducing military government supervision below the Land level. "We cannot," he said, "expect the Germans to take responsibility without giving it to them. We don't want the low level job; we want the Germans to do it." He added, "We are going to move a little fast . . . ." 37

On 5 October, USFET announced:

It has always been the purpose of the US Forces to permit the German people

to develop a free government, shaped to fit the needs of Germany. Moreover,

it is manifestly simpler to control Germany through German administrative machinery

than by undertaking direct operating responsibilities . . . .

"In order to carry out this conversion," USFET ordered the Landkreis and Stadtkreis detachments to divorce themselves from direct supervision of the German civilian administrations by 15 November 1945 and the Regierungsbezirk detachments to do so by 15 December. After the last elections (and no later than 30 April 1946 in the Landkreise and 30 June in the Stadtkreise) , the directive added, the Landkreis and Stadtkreis detachments would be disbanded and replaced with two-officer liaison and security detachments, which would observe and report on the German governments and act as the link between them and the occupation forces but have no authority, except in emergencies, to intervene in their operations.38

OMGUS, the Land offices of military government, the German Land governments, and a Laenderrat (council of ministers), consisting of the Land minister presidents and the Oberbuergermeister of Bremen, were to be the vehicles of authority in the US zone. Bavaria had had a Land government since June. One Land government was installed in Wuerttemberg-Baden on 24 September and another in Greater Hesse on 8 October. On the 17th, Clay opened the first meeting of the Laenderrat in Stuttgart. Clay indicated, on the one hand, that he regarded the Laenderrat as a zonal substitute for the central authority that the Control Council had failed to establish. On the other hand, to avoid seeming to have accepted the Control Council's failure as final, he pointed out that the Laenderrat was neither a legislature nor a zonal executive but was only charged with co-ordinating legislation in areas where zone-wide uniformity was necessary.39 The Laenderrat began to function officially at its second meeting on 6 November. By then a joint coordinating staff composed of representatives of the Land ministeries, a permanent secretariat, and a US advisory group the Regional Government Coordinating Office (under Dr. James K. Pollock)-was established.

From the field, USFET survey teams described the reaction of military government officers as "100 percent" against the impending removal of the local military government detachments. Some officers saw

[404]

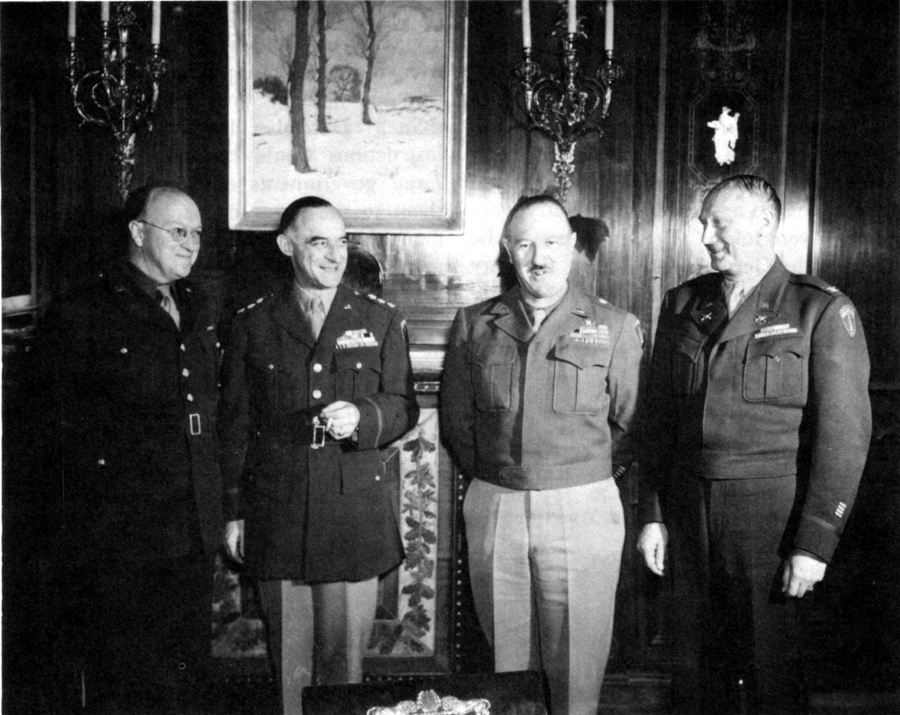

GENERAL CLAN (Second from left) AT LAENDERRAT MEETING. On his right Regional Government Co-ordinator, Dr. Pollock. On his left General Muller and Colonel Newman, Military Government Directors for Bavaria and Greater Hesse.

the move as a kind of trick to reduce their staffs without reducing the work loads. Others protested that the German officials were too recently appointed and too inexperienced to have any idea of how to operate the governments on their own initiative. Many believed the Germans "would quickly revert to their old political, economic, and social customs"; and the Germans themselves reportedly feared a resurgence of Nazi elements and doubted the ability of the civilian officials to run the governments or to maintain public peace and order. OMGUS hoped that such pessimism could be written off as the natural reaction of a large organization threatened with a drastic reduction in its scope and activities, and Clay let the withdrawal of control from the Kreis detachments go ahead in mid-November. The organization was not going to be there much longer in any event. The detachments had lost an average of 50 percent, and in some instances as much as 80 percent, of their enlisted men in October. The officers, if held to the letter of their commitments, could

[405]

have been retained six or eight months at most.40

On 21 November, USFET granted full executive, legislative, and judicial authority to the Land governments individually and extended to them all the powers formerly exercised by either the Land or the national governments. The offices of military government were told, "The initiative must be taken by the German authorities: the duty is theirs." All legislation issued by the Land governments was to be on their authority alone and "contain nothing to indicate that it was issued in the name of or having the approval of military government"; however, it was still subject to prior clearance through military government. Not later than 31 December 1945, US orders and instructions would be issued only to the Land governments and would pass from them to the lower elements through German channels. Similarly, military government would intervene to correct mistakes or deal with violations only at the Land level. 41 Military government as conceived at Charlottesville, shaped at Shrivenham, and deployed under the Carpet and Static Plans had served out its time.

[406]

Return to the Table of Contents