CHAPTER XXIV

Neither an End Nor a Beginning

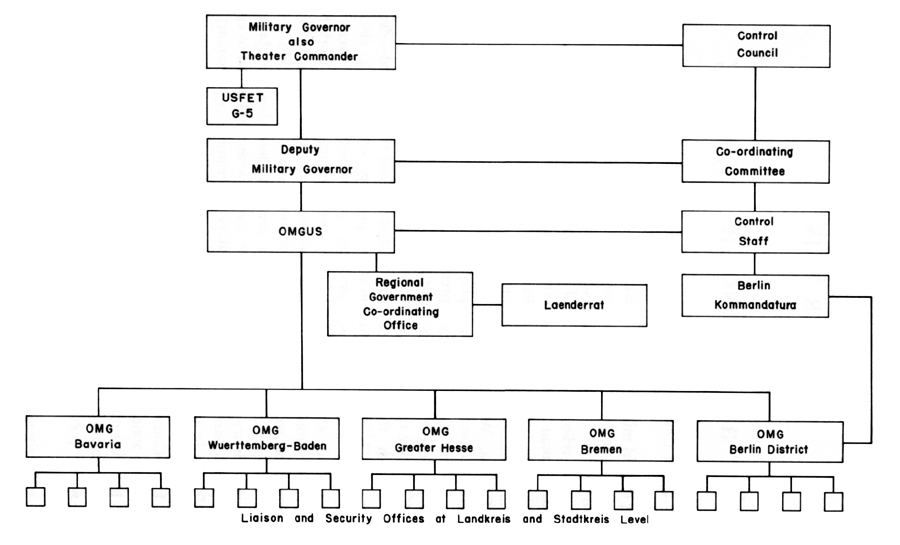

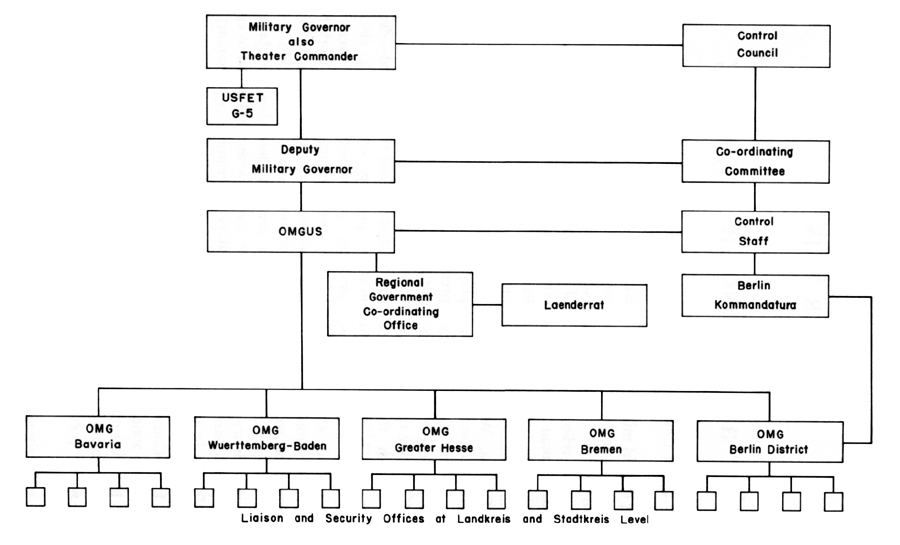

The dismantling of field military government was accomplished in less than two months. The Kreis and Regierungsbezirk (regional) detachments relinquished most of their functions to German appointees in November and December 1945, and on 1 January 1946, the Offices of Military Government for Bavaria, Wuerttemberg-Baden, and Greater Hesse became independent commands reporting directly to the Office of Military Government (U.S. Zone) and to OMGUS. By then only four functions remained with the Office of Military Government (U.S. Zone) in Frankfurt: legal, public health and welfare, public safety, and civil administration. When the Land offices of military government became independent commands, the army-military district commands lost their authority to supervise military government; and in January, Headquarters, Seventh Army, began transferring its personnel and functions to Third Army, which would take command of the U.S. Constabulary and all tactical troops in the zone. 1 (Chart 3)

As an OMGUS historian observed later, the German civil government did not break down as had been widely predicted earlier, but the burden of occupation on the Army was not much lightened either. The civilianization program, which was to have accompanied the transfer of functions, was barely getting off the ground. The offices of military government had established civilian personnel sections, but the job allotments were enmeshed in civil service procedures. Meanwhile, officers eligible for civilian appointments were choosing redeployment when their numbers came up in preference to the uncertainties of the occupation.2 The detachments had given up most lout not all of their functions, and the three out of the four they retained-denazification, property control, and elections (military government courts were the fourth)-were increasing their work loads as redeployment diminished their strengths. Denazification cases under Law No. 8 were at their peak in December and January; property control alone threatened to engulf the military government organization; and the detachments were having to observe the campaigns and screen the candidates and voters in the forthcoming elections.3

Whether the Germans were able or willing to assume responsibility for their own affairs remained the big question. One detachment report described the transfer of functions and the elections scheduled for

[425]

CHART 3-U.S. MILITARY GOVERNMENT RELATIONSHIPS AFTER 1 APRIL 1946

[426]

January as constituting for the German people "a bum's rush into what passes for democracy." 4 The Office of Military Government for Wuerttemberg-Baden detected "a glorification of disinterest in politics among large sections of the population." 5 The chief obstacles were what the Germans themselves described as their "burnt finger complex," resulting from their earlier excursions into politics, and the known inability of German parties or officials to influence decisions on the real issues of the time, such as denazification or the economic and political future of the country. In the weeks just before the election, the word "apathy" cropped up in almost every report on the reaction to the campaigns. As the Office of Military Government for Greater Hesse reported:

The leading posts in the parties are held by former minor political figures who, because of their insignificance, were not accorded by the Nazis the distinction of being exterminated. They have retained the political mannerisms of pre-1933. Negotiations, blocs, and conferences are all being widely indulged in. This continual activity, however, involves only a few with the masses still keeping their distance.6

The January elections were for local councils in 10,429 communities with less than 20,000 people. Beforehand, the military government detachments checked the 4,750,000 names on the voting lists for Nazis (and disqualified 326,000) and reviewed the Fragebogen of all the candidates for the nearly 70,000 seats on the councils. The Germans went to the polls on the last Sunday in January, and they went in astonishingly large numbers-86 percent of those eligible voted.

In Bavaria, the CSU, with 43 percent of the vote, was the strongest party, and the Social Democrats were a poor second with less than 20 percent. The CDU, with 31 percent of the vote, outstripped the Social Democrats in Wuerttemberg-Baden by a third, while the Social Democrats in Greater Hesse took 40 percent of the vote to the CDU's 30 percent. The Communists and the liberal parties each polled less than 5 percent. Throughout the zone, the CDU-CSU's 37 percent of the vote made them the leading parties. In rural districts they were by far the strongest parties, and their lead would undoubtedly have been greater if all candidates in the small rural communities had announced party affiliations.7

The heavy turnout for the January elections was a surprise that OMGUS found "particularly gratifying" because it put local administrations, until then entirely appointed by military government, "on a basis of some popular support and understanding." 8 Whether the vote represented an awakening of interest in democratic self-government, however, was doubtful. The success of the CDU and CSU, in spite of their leniency toward Nazis, seemed vaguely ominous to many military government officers, and the parties' close ties to the Catholic Church suggested that their constituents were voting as they were told from the pulpit and not from inner conviction. The Social Democrats, however, seemed to have attracted a large part of their vote

[427]

simply as an anti-Catholic protest. Some observers believed the Germans had voted mainly "to convince themselves and their neighbors that the stigma of Nazism had been eradicated not because it was their patriotic duty to elect men who could lead them to democracy." 9 The Office of Military Government for Greater Hesse made the following analysis:

The striking impression that observers received of the elections was the fantastically high percentage of eligible voters participating. Whether it resulted from a lively interest in the issues and in the opportunity to share in the democratic process, whether it was the desire to do what military government expected of them, or whether it was another example of obeying their superiors it is difficult to say. One thing became clear, however . . . the German people had not suddenly shaken off the past and embraced democracy. They had voted, but the political principles were obscure and the faith of the people frail and uncertain.10

Similarly, OMGUS itself concluded, "While the voting in the recent elections was gratifying, the fact remains that the average German does not yet recognize the personal responsibilities which go with political freedom." 11 The least optimistic analyses came from Bavaria. From there the regional detachment for Upper Bavaria reported, "In this situation a minority of political opportunists, with little actual popular support, organized a disinterested public into political parties and encouraged them to vote in the first election." Spontaneous political interest, the report concluded, was no more apparent after the election than it had been before.12

Alongside politics, denazification held its place as a sore subject. From the beginning Americans had been of two minds: officially they regarded nazism as an unmitigated evil and anyone tainted with it as corrupted beyond redemption; however, more than a few believed that the fine mesh of the Nazi party's net had snared too many Germans for them all to be judged by a single standard. Some actions, such as the use of the 1 May 1937 cutoff date in distinguishing between active and nominal party members, tended to reflect the second point of view. But the dominant trend in the summer and fall of 1945, culminating in Military Government Law No. 8, was toward elevating the idea of permanent taint to the status of doctrine and applying it to broader segments of the population: first to those in public employment, then to businesses with a public aspect, and finally to all private business. For the Germans in all categories who were affected, U.S. policy provided just two possibilities: exclusion from public and private employment above the level of common labor or, if they were important enough to rate automatic arrest, exclusion with a prospect of some punishment yet to be decided.

Denazification had made the Army the warder for dozens of internment camps and made military government the custodian of thousands of Nazi properties, piled up backlogs of Fragebogen and appeals cases in detachment offices, and left to military government officers the jot) of tutoring inexperienced German officials while keeping track of the discharged Nazis. Clay later

[428]

VOTERS CAST THEIR BALLOTS

described the total result as an "administrative problem," which it undeniably was, and more.13 As has been indicated, trying only the Nazis who might be implicated in criminal organizations could have occupied a battalion of judges for months or even years. As long as Military Government Law No. 8 and the exclusion of Nazis from public and private employment had to be enforced by Americans, military government strength in the field would have to be maintained at levels that even in the fall of 1945 were not feasible; and as the Schaeffer and Patton incidents had demonstrated, as long as the Americans retained the entire responsibility for' denazification, the whole occupation was fused for a political explosion.

In his address to the first meeting of the Laenderrat (17 October 1945) , Clay hinted that the judging of Nazis would eventually be left to German tribunals. During a session on 4 December, he told the minister presidents that the German people should take denazification into their own hands and directed each of them to have a denazification plan for his Land; and after the Minister President of Greater

[429]

Hesse, Dr. Karl Geiler, recommended that the regulations be uniform in the three Laender, the Laenderrat appointed a committee to write a statute for the entire zone. Clay's advisers, Lt. Col. Fritz Oppenheimer, Dr. Walter Dorn, and Dr. Karl Loewenstein, assisted the Germans.

From the beginning the German approach differed from the American in two fundamental respects. While the Americans had in the main only distinguished between active and nominal Nazis, the Germans recognized several gradations, particularly within the group the Americans had regarded as active, and eventually settled on five: major offenders, offenders, lesser offenders, followers, and exonerated. Secondly, where the Americans had imposed presumably permanent exclusion from positions of influence in public or business life on all active Nazis, the Germans adopted a scale of sanctions keyed to the offense.14

In the Germans' hands the meaning of denazification also changed. Under military government it had meant the removal of party members from positions of influence in the government and private occupations. To the Germans it meant removal of the Nazi stigma from the individual and his reinstatement in society. The early drafts of the German law would have imposed employment restrictions and loss of voting rights on major offenders and lesser restrictions or none at all on followers. The OMGUS advisers, however, although they appear not to have objected to seeing ex-Nazis denazified and restored to social and political equality, insisted that nazism be regarded not merely as a serious lapse in judgment but as a crime and demanded that the Germans include a schedule of punishments in the law: up to ten years imprisonment for major offenders, five years or less for offenders, fines to 10,000 marks for lesser offenders, and fines to 1,000 marks for followers. The fines, the Americans undoubtedly knew, would be paid in inflated money and hence have small punitive effect, but they would, by forcing a hearing in every case, prevent blanket acquittals.15 The negotiations on the German law almost broke down in January and February 1946, when the Americans also insisted that it conform with Control Council Directive No. 24 of 12 January 1946. The drafts of the German law had categorized as major offenders only persons who had held relatively significant posts in major Nazi organizations or general officer rank in the military and had been "activists." 16 Control Council Directive No. 24 listed ninety-nine categories of persons who would be classed as major offenders and offenders and recommended very close scrutiny of all career military officers, persons "in the Prussian Junker tradition," and members of university students corps, as well as various others.17 But the time had not yet come when German officials could stand out against the occupation authority.

On 5 March 1946, in Munich, the minister presidents, without enthusiasm, signed Law No. 104 for Liberation from National

[430]

Socialism and Militarism. More comprehensive than anything military government had attempted, the law would in some degree affect 13.5 million persons, that is, every resident of the U.S. zone over eighteen years old, all of whom would be required to submit a Meldebogen, a shortened form of the military government Fragebogen. Those with chargeable associations (eventually 3.6 million) would have to appear before Spruchkammer, tribunals of local, non-Nazi citizens somewhat similar to U.S. draft boards. The Spruchkammer, after hearing evidence on both sides, would place the defendants in one of the five categories and assess the penalties accordingly. Those who were exonerated or paid fines were considered denazified and recovered their full civil rights.

The Law for Liberation from National Socialism and Militarism, like other earlier important changes in occupation policy, burst as a surprise on both the German population and military government in the field. General Clay has described the decision to turn denazification over to the Germans as "controversial when it was made." 18 He was right. As a first reaction, the regional detachment at Kassel reported, "Greater confusion never existed in the denazification program." 19

The German man on the street construed the law as a wholesale indictment of the German people and expressed fears that it would provoke unrest, strip the country of its most qualified people, and permanently undermine the economy. The political leaders were caught with a law to which they were committed and, hence, could not criticize openly but which they could not defend either without seeming to subscribe to the collective guilt theory.20 Some American observers, however, believed the Germans were less apprehensive about the law then they appeared to be. The detachment in Landkreis Laufen reported, "The average man is of the opinion that the denazification task was turned over to Germans for the sole purpose of clearing the Nazis. The usual remark when the news of the new German denazification law was released was, 'Thank God. In two or three months I'll have my old job or my business back!' " 21

Military government opinion on the German law ranged from skeptical approval to outright condemnation. As the Office of Military Government for Wuerttemberg-Baden reported:

The new denazification law, with its provisions for the certification of all

German males and females of eighteen years of age and over, and for

classification of the population into political categories, bore a revolutionary

character. It established a judicial process for the purging of a people and

ridding it of the destructive elements which brought disaster upon them in the

course of three successive generations. It was obvious that in order to

accomplish its purpose, the new law had to become the manifesto of a strong,

popular, anti-Nazi movement, much stronger and more popular than had existed

heretofore.

But . . . only relatively few groups in the area had evinced

the moral courage and historical insight necessary for the carrying of the

denazification program to its logical conclusion.22

The Office of Military Government for Bavaria dismissed the law as "legislatively

[431]

and politically foredoomed to failure." The parties, the Bavarian assessment continued, were aware that the ex-Nazis would comprise a formidable voting bloc and, therefore, would, while giving lip service to denazification, manipulate the law to attract the Nazi votes.23 The CSU was already refusing to nominate a candidate for the Land ministry charged with administering the denazification law and at the same time demanding representation on the appeals boards in full proportion to its electoral strength. The regional detachment for Upper Bavaria added that the law was unenforceable because military government could never do more than spot check the millions of cases and because "incorruptible administrators are impossible to find in Germany today." The regional detachment concluded, "The best thing to do is to wash our hands completely of it and tell the Germans that from now on it is up to them whether they denazify." 24

While the elections and the Law for Liberation from National Socialism and Militarism touched off squalls of controversy in Germany, one of the chief reasons for their existence -the projected shift to State Department control of the occupation- was having even rougher going in Washington. On 18 December, Secretary of War Patterson talked about the shift with Acting Secretary of State Dean Acheson and Assistant Secretaries of State James Dunn and Donald Russell. Patterson reviewed the War Department's reasons for wanting the transfer, and the State Department representatives proposed that the responsibility remain with the War Department on a civilianized basis or that it be lodged with the SWNCC or that it be moved to a new agency -"anywhere," Patterson later declared, "but in the State Department." 25 During the next several weeks both Patterson and Eisenhower attempted to convince Secretary of State Byrnes that the State Department should assume control of civil administration in occupied areas. Other solutions, such as setting up a new agency, Patterson argued, would not work because the State Department would still be responsible for policy, and civilian administration under the War Department would not be "forthright civilianization." 26 But on 21 January Eisenhower cabled to McNarney:

My best efforts and those of Sec. War have been devoted to forcing a decision that State Department assume control of administration of military government in Germany on or before 1 June. So far efforts have been completely unavailing. War Department will continue to press . . . however, am without hope that issue will be settled to our satisfaction in the near future.27

On 1 April, the Office of Military Government (U.S. Zone) closed in Frankfurt. Headquarters, USFET, was therewith divorced from military government, and control would henceforth be exercised exclusively by OMGUS in Berlin; but the next step, appointment of a civilian high commissioner, was in the distant future. At the end of the month the Secretaries of State, War, and Navy endorsed a memorandum on principles and procedures for administration of occupied areas which reaffirmed

[432]

the division of policy-making and executive responsibilities between the State and War Departments made in August 1945, adding only a somewhat enhanced role for the SWNCC and a Directorate for Occupied Areas to be formed under the SWNCC. 28 In its last paragraph, the memorandum provided for consultation between the War Department and the State Department concerning the appointment of a high commissioner, "In the event that it is decided to reconsider the pattern of American control machinery during the period of War Department responsibility . . . ."

Spring came early to Germany in 1946 but brought no renewed hope, either for the people or the nation. On 5 March at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, Churchill talked about the iron curtain that had descended across the European continent from the Baltic to the Adriatic. Out of office, he could say what those in office knew but could not yet tell to nations which still expected a better reward for their wartime sacrifices: the world was divided and would likely remain so for years to come. Nowhere was the division clearer than in Germany.

The one substantive step toward putting into effect the Potsdam decision to treat Germany as an economic unit was the level of industry plan. Completed on 26 March 1946, the plan proposed to reduce the German industrial capacity to about 55 percent of the 1938 level and cut the standard of living (in comparison with 1938) by 30 percent.29 In the U.S. zone, 185 plants had been earmarked for reparations and more were being surveyed, but the real problem, in the view of U.S. authorities, was not to keep Germany down to the contemplated levels but to restore the country's ability to support itself. Since Germany imported food during the best of times, the one way to restore the import flow was to secure sufficient exports to pay for essential imports. In December 1945, OMGUS had submitted a draft agreement, based also on a Potsdam decision, for an export-import program to be operated by the Allied Control Authority for Germany as a whole.30 After the British had accepted the proposal with some reservations and the French with more, the Russians, in the first week of April 1946, rejected it outright, declaring they would "adhere to the principle of zonal foreign trade and individual responsibilities of the countries for the results of the occupation in their zone." 31 On 3 May, citing the interrelationship of the level of industry plan and the export-import program Clay announced in the Control Council Co-ordinating Committee that, except for two dozen plants already allocated, the United States would halt all dismantling for reparations in its zone "until major overall questions are resolved and we know what area is to compose Germany and

[433]

whether or not that area will be treated as an economic unit." 32 (Map 3)

The division was in the open. War rumors, which had never quite died out, again swept across the country. Some Germans seemed to welcome the thought of a war, because they envisioned an East-West clash as a chance for Germany's salvation or, simply, because it would give them an opportunity to say, "I told you so." The more sober minds, however, were painfully aware that Germany could only suffer from any controversy between the Allies, military or otherwise. 33

In the spring OMGUS launched an export-import program for the U.S. zone and secured orders for $16 million worth of hops, salt, potash, filtration sand, and lumber while simultaneously making commercial import commitments (the first in the zone since the surrender) for vegetable and field seeds. The Economics Division put on a Bavarian export show in Munich in May, and in June sent samples of dolls, toys, chinaware, cameras, and Christmas tree ornaments by air express to the U.S. Commercial Company, a subsidiary of the U.S. Commodity Credit Corporation, for display in New York. In June, also, the Economics Division arranged with the Commodity Credit Corporation to import 50,000 tons of American raw cotton, which was to be paid for by exporting 60 percent of it as finished textiles, leaving 40 percent for the Germany economy. But the program was small and bound to remain so for a long time. The deficit, however, in terms of food and other items that military government was importing for the benefit of the Germans, was large and growing. Between 1 August 1945 and 30 June 1946, the dollar-based import commitments for Germany amounted to $242,285,000, and the total value of exports actually chargeable against this sum was $7,277,000. 34

Owing chiefly to increased coal receipts, industrial output in the zone rose measurably during the first quarter of 1946, reaching an estimated 31 percent of the 1936 level. The hold on even this much of a gain was precarious, however, and the obstacles in the path of further progress were formidable. The most important obstacle was the country's lack of a currency. Except for purchases of a small and dwindling selection of rationed items, the Reichsmark had no domestic value and was worthless internationally. With military government sometimes protesting and sometimes promoting, barter had become the norm in business transactions. Nothing moved in trade, not the farmer's potatoes nor the output of factories, except in exchange for some other commodity. The worker found it profitable-and often essential for survival-to spend more time trading on the black market than working on his job, since his salary bought nothing but the daily ration. Clay, in March 1946, appointed Joseph M. Dodge of OMGUS and Gerhard Colm and Raymond Goldsmith, borrowed from Washington, and a staff of economists to devise a currency reform. They had a plan ready in six weeks, but owing to Soviet and French opposition in the Control Council, two years more would pass before Germany had a working currency. 35

[434]

Meanwhile, the zone was supporting a permanent population of half a million DPs, as the Germans being expelled from eastern Europe flooded in. An average of 45,000 of these expelled Germans came each week in May and June totaling 920,000 by the end of June.36 Only 12 percent could be classified as fully employable; 65 percent needed relief. Contrary to agreements made before the movement to keep families together, the countries expelling Germans were holding back the young, able-bodied men. Of the arrivals, 54 percent were women, 21 percent were children under fourteen years, and only 25 percent men, many of them old or incapacitated.37

An additional, significant obstacle to German economic self-sufficiency, in Clay's view, was the occupation force, which had pre-empted a large share of the zone's industrial output-as much as half in the case of building materials such as glass and cement. While the costs were presumably being charged to the Germans, Clay pointed out to McNarney, they were actually being borne by the U.S. taxpayers at the rate of over $200 million a year for relief supplies, and this situation would continue until the German economy could produce enough to pay for imports. In a statement that Colonel Hunt would have thoroughly approved, Clay told McNarney:

Difficulties in discipline, fraternization, disposal of surplus property, guarding of internees, and similar problems, while difficult to solve now, have little if any bearing on history. The bringing of a measure of self-sufficiently to the German people and the institution of self-government under democratic principles, if successful, will stand out in history and perhaps will bring a major contribution to the peace of Europe and the world. 38

For the average German, however, the most pressing concern in the spring of 1946 was food. The daily ration for the normal consumer in the British zone dropped to 1,042 calories a day in March and in the French zone to 980 calories; the newspapers predicted a cut by as much as 50 percent in the U.S. zone. Grain imports for the zone, which at 100,000 tons a month in the last quarter of 1945 had not been enough to support the 1,550-calorie ration indefinitely, fell below 50,000 tons in February 1946. 39 Germany was feeling the impact not only of its own but of a worldwide food shortage. The war had converted large areas in Asia and the Pacific, which had been self-sufficient and had exported vegetable fats and oils to Europe, into food deficiency areas and had reduced European production by an estimated 25 percent. 40 With almost the whole world waiting in line, the Germans could easily guess that they would not be at the head. On 21 March Brig. Gen. Hugh B. Hester of OMGUS went to Paris to see former President Herbert C. Hoover who was in Europe on the first of his postwar relief missions for President Truman. Hoover said he felt as he had in 1918, that "We will have to feed the Germans"; but he would not go to Germany or make any commitments for it until he had visited the liberated countries. Asked how he would stretch out feeding the Germans, Hoover replied: "General, I would give as much

[435]

A 1,275 CALORIE DAY's RATION, displayed here as a single meal.

as I could in April, a little less in May, a little less in June and hope the sunshine and flowers would keep you up through June. And maybe by that time we could do something for you." 41

Clay had no other choice than to do as Hoover advised. Accordingly, he reduced the ration in the U.S. zone on 1 April to 1,275 calories, which was still about a third more than the indigenous supplies could sustain. In the fourth week of May he had to reduce again to 1,180 calories. To meet these levels the Army in April and May released from its own stocks over 30,000 tons of cereals, canned goods (corn, peas, and tomatoes), dried skim milk, dehydrated potatoes, and dessert powder. 42 The introduction of corn and corn flour beginning in June into the German diet was taken by many Germans as a form of reprisal, since until then corn had been con-

[436]

sidered in Germany only suitable as feed for chickens. Many of the released Army supplies were, in fact, low in caloric value. When McNarney talked to Hoover in Frankfurt late in April he pleaded for shipments of wheat, arguing that Germany could not be democratized and would remain politically unstable as long as the people were forced to devote all their thought and effort to the daily search for food.43 Earlier in the month, after small disturbances had been reported in the British zone, Clay and McNarney had issued a press statement warning that the food crisis might "lead to unrest which may necessitate a larger army of occupation for a longer period of time." 44

After 83,000 tons of food arrived from the United States in the first three weeks of June and an almost equal amount was en route, Clay raised the ration to 1,330 calories per day on 24 June. Close to half the tonnage, however, was Army surplus food scoured out of depots around the world which, while helping to fill stomachs, could not increase the caloric value of the diet as much as an equal amount of grain would have. The crisis in any case was far from over. In Bavaria the bakers mixed 10 percent raw potatoes into the bread dough, and without continuing imports from the United States, there would lie no bread at all in four to six weeks.45 Short on fertilizer, machinery, and labor, the zone's agriculture was not likely to produce as good a crop in 1946 as it had a year earlier. To make matters worse, farmers were hoarding thousands of tons of food to sell on the black market, and the unemployed, many of them former white collar workers who feared a loss of social status, were refusing jobs as farm laborers. Meanwhile health checks, such as the one in Mannheim in which 60 percent of the infants showed signs of rickets, revealed increasing evidence of malnutrition among the city populations.46

To add to the strains on the unsettled and unhappy country, violence of all kinds, excepting resistance to the occupation authorities, increased in the early half of 1946. Incidents caused by U.S. troops, if no more numerous than they had been in the last months of 1945, were certainly no fewer; they included, as they had earlier, wanton killing, looting, and threats and assaults on German police and civilians. In May, Jewish DPs in big camps at Foehrenwald and Landsberg, Bavaria, rioted against both the Germans and the Americans for no better reason apparently than the unfounded rumors that some Jews had been kidnapped. Attacks by Germans on American soldiers, almost unheard of before, were increasing too, mostly because of fraternization between soldiers and German women. German men resented the women's willingness to consort with U.S. soldiers, the soldiers' affluence, and their own inability to rank even as minor competition for the

[437]

Americans. The Negro troops, who were making up an increasing proportion of the occupation force, were particularly resented by German men; and the Negroes, believing they were not getting an equal share of the women, nursed grudges against both the Germans and the white Americans.47

Evidence that the Edelweisspiraten and other underground clubs were growing and that the zone harbored what was becoming a permanent subculture of vagrant young people revived concern for the German youths. In April, the Munich police picked up over 900 vagrants less than twenty-one years old, nearly a quarter of them girls. The Bavarian Red Cross had 11,000 vagrants listed. It maintained Wanderhoefe (homes) for them, but few, especially those in the seventeen to twenty-one age group, stayed more than a few weeks. The director of one Wanderf described the boys as "completely cold and blase, entirely calculating in what they do. They have lost every feeling of relationship with their homeland and home with parents and relatives, even with their mothers. Memories mean nothing to them. Their only interests are food, sleep, money, and girls." 48 One example, certainly not typical but not unique either, was a 12 year-old boy whose father, an SS officer at Mauthausen concentration camp, had committed suicide. The father, according to rumor, had used concentration camp prisoners for rifle practice. The mother was interned at Dachau as a potential war crimes defendant. Placed in a children's home after having spent most of his life in far from edifying adult company, he adapted quickly and proved to be more clever than the average child; but his counselor observed, "He plays with others and laughs and romps with them but has no close ties with any of the children or the teachers." 49 The young people who had homes and families but lived in bombed-out cities and went to overcrowded, barely functioning schools were not much better off. Boys roved the streets, and girls in their early teens looked for soldier-boyfriends or experimented with amateur prostitution.50

In April, McNarney ordered all military government, divisional, and higher headquarters to assign mature officers to check into the youth problem "with a view toward correcting these conditions and increasing proper youth activities that will keep these young people out of trouble . . . . If we fail in this," he added, "we are simply making future trouble for ourselves." 51 During the next month, the Land offices of military government organized youth committees and sent youth activity liaison officers to the tactical units. In Bavaria, for a start, Lt. Col. Kenneth E. Van Buskirk, special youth adviser to the Office of Military Government for Bavaria, secured from captured Wehrmacht stores 4,000 pairs of skis, 3,000 jackets, 6,000 pairs of ski pants, 70,000 caps, and 40,000 knapsacks. By mid-June, when the youth advisers held a four-day meeting in Munich, Kreis youth committees had been organized in every Kreis in Wuerttemberg-Baden and Greater Hesse and in more than half of the Ba-

[438]

varian Kreise. By then military government had approved 2,500 youth groups with a total membership over 300,000; and the tactical units were supplying athletic equipment and instructors to teach American games and were releasing or sharing requisitioned gymnasiums, swimming pools, and sports fields.52

On 5 May every German in the U.S. zone over eighteen registered under the Law for Liberation from National Socialism and Militarism and filled out the required Meldebogen. Hearings were scheduled to begin ten days later, but in most places during the two months the law had been in effect, the military government detachments had not been able to find enough men to staff the tribunals and act as prosecutors. The law required tribunal members to be local residents, known opponents of nazism and militarism, personally beyond reproach, and fair and just. Detachment E-291 in Landkreis Wolfrats-hausen, Bavaria, reported that finding competent prosecutors and judges was impossible; no one, whether anti-Nazi or not, wanted to judge their own friends and the people they had lived with all their lives.53 People in Landkreis Dillingen, Bavaria, were convinced that men who accepted appointments as prosecutors or chairmen of tribunals would have trouble for the rest of their lives, and the local detachment recommended bringing in strangers who "could leave town after it was over." 54 Captain Boring, in Landkreis Laufen, drew up a list of twenty-one passive anti-Nazis. There were not twenty-one active anti-Nazis in the Kreis, he said. The prosecutor for Laufen declared outright that he expected to be a ruined man.55 Detachment G-297 in Landkreis Neuburg, Bavaria, said of its candidates: "They made a very poor impression. Some appeared to be semiliterate, others borderline mental cases. The ten most acceptable were selected and approved." 56

A tribunal at Fuerstenfeldbruck, Bavaria, held the first trial in the U.S. zone on 20 May 1946. Three defendants pleaded guilty to having beaten an anti-Nazi in 1933 and were sentenced to three years at hard labor, confiscation of property, and prohibition from working at anything but ordinary labor for ten years.57 In the first case tried in Wuerttemberg-Baden, at Heidenheim on 12 June, a former labor front official was found to be an offender and sentenced to imprisonment and loss of property.58 These two decisions were not enough, however, to lay to rest the doubts about the outcome of denazification in German hands. Detachment E-291 reported on tribunals it had observed, "Verbal evidence by the defense, and usually by Nazis testifying on behalf of another Nazi, is given more weight than documents submitted by the prosecution." 59 The Office of Military Government for Bavaria assessed the German responses as follows:

Those who had clear consciences were hoping the law would wipe out the compara-

[439]

tive wealth of the Nazis; those whose consciences were not so clear were sending their wives to bribe the wives of the members of the Spruchkammer, or trying to transfer property to persons politically clear, or preparing to move to some other zone where the laws were not so harsh, or just waiting for their fate. While the Nazis were scurrying to avoid trial, members of the Spruchkammer seemed just as eager to avoid prosecuting. They either disliked the "toughness" of the law or feared reprisals later. The Land political parties were paying lip service. Especially stubborn was the CSU which stood to lose the most by adopting a strong policy.60

But, once more, for denazification the time for discussion was past. On 14 June, OMGUS rescinded all existing military government denazification directives; the responsibility passed to the Germans.61

On 28 April and 26 May the Germans in the U.S. zone went to the polls to elect Landkreis and Stadtkreis councils. American reactions ranged from satisfaction in OMGUS with the still high turnouts-72 percent in the Landkreise and 83 percent in the Stadtkreiseand with the signs that the electorate were not reverting to their pre-Hitler habit of backing splinter parties (only the CDU and CSU and the Social Democrats drew significant percentages), to skepticism of German democracy at the lower military government levels and some apprehension over the heavy vote for the CDU and CSU. 62 Whatever the elections meant for the future of democracy in Germany, they spelled the end for local military government. The Landkreis detachments became liaison and security offices on 1 May, and the Stadtkreis detachments were redesignated on 3 June.

Within military government, the withdrawal of the detachments was accompanied by an eleventh-hour drive to civilianize before the end of June. The 194 liaison and security offices, each composed of two officers and two enlisted men, were not affected since they were to remain military personnel for the psychological effect of the uniform. These offices had personnel problems of their own, however: more than a few were in the condition of D-357 in Landkreis Neumarkt, Bavaria, which consisted of two officers, neither trained in military government and both several months overdue for redeployment, and two 19 year-old privates, both also untrained.63 Clay reported at the end of June that the ratio in OMGUS was two civilians to one officer, and he expected to reach similar ratios in the Land offices in sixty days.64 But as of 30 June, the personnel situations in Bavaria and Greater Hesse were probably not much different from that in Wuerttemberg Baden where only 90 out of a total of 560 workers were civilians.65 The military government officer was going to be in evidence for a while yet; and in April, the School for Military Government, which

[440]

had graduated its last class at Charlottesville in February and had not trained any officers for Europe since 1944, reopened at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, to give four-week courses to the estimated 3,000 replacement officers that military government in Germany would need in 1946.66

Fully divorced, finally, military government and the tactical commands in the spring of 1946 were again experiencing friction with each other or, at least, what McNarney described as "a definite loss in friendly co-operation." In the field, the friction stemmed, as it had in the past, from the disparity in ranks and in higher echelons, in part, from civilianization. Owing to redeployment, the military government officers in the field were, if anything, even more junior to their counterparts in the tactical commands than they had been in 1945. At the higher levels, Clay complained, "Many times U.S. civilians and military do not look at each other . . ." 67 On the one hand, the tactical commands from USFET on down did not relish being in a support role where they had once been in command. Recognizing this feeling, Clay told the OMGUS divisions they should not "send cables to USFET telling them what to do . . . [but] call for help instead." 68 On the other hand, it did not seem in OMGUS that the tactical commands had correctly assessed their part in the occupation. On this score, Clay wrote to McNarney;

My philosophy . . . envisions the Army of Occupation as having a dual

responsibility in Germany. First, to provide such force as necessary to ensure

carrying out the objects of the occupation, that is, support of military

government. Second, since military government itself is a responsibility of the

Army, it is most important that the Army handle this civil responsibility of its

own accord with somewhat the same relation between tactical troops and military

government as exists at home and in our prewar overseas stations.

A civilian high commissioner should not show later a more zealous interest in

safeguarding the German economy in the interests of the U.S. budget and in the

interest of our object to bring democracy to Germany than does the Army now.

If this is a sound philosophy, then your position as theater commander is separate

and distinct from your position as Military Governor, and the proper balanced

relationships between your staffs are essential.69

The balance that needed to be found was between a victorious army living in a conquered nation and an army becoming increasingly concerned for the welfare of its former enemy. In OMGUS opinion the area in which the most serious imbalance existed in the spring of 1946 was that of housing requisitions. The Land offices of military government all complained that there was an inverse ratio between the redeployment of troops and the number of rooms occupied by the troops. The Office of Military Government for Wuerttemberg-Baden, for instance, found that while troops had occupied 29,394 rooms in the Land in November 1945, the number rose to 42,002 in December and 43,361 in January. 70 However, when Clay expressed surprise that after a reduction from over three

[441]

million troops to less than half a million, the Army was still requisitioning houses, General Barker, USFET G-1, explained that the troops were now living in smaller groups.71 The Land offices of military government, on checking, also learned that large parts of the increases were belated formal requisitions of houses occupied months before, but they still complained that too many requisitioned buildings were being left vacant or underoccupied. In April, USFET authorized military government to "act as a buffer between the communities and the tactical commanders" and empowered it specifically to prevent houses from being taken from U.S. appointees (which had been a recurring embarrassment to military government) or from Germans who had put much personal effort into repairing their homes.72

For the tactical commands the problems in the spring of 1946 and after, as the renewed tension with military government evidenced, were to overcome the shock of redeployment and settle into the status of a permanent occupation force. When Headquarters, Third Army, moved from Munich to Heidelberg on 1 April and became the ground forces command for the U.S. zone, the troop shipments out of the theater still by far exceeded arrivals, and the reinforcements coming in were overwhelmingly recent draftees with only accelerated basic training. Surveys in reinforcement depots in May showed 85 percent of enlisted assignments and 64 percent of officer assignments to the Ordnance and Quartermaster Corps had been made without regard to capabilities.73 The U.S. Constabulary, projected as an elite force, was having to accept the average spread of reinforcements and had authority only to reject illiterates, men who did not speak English, and outright undesirables.74 While military government reported improvement in troop conduct and discipline in May, the rate of incidents was still high in proportion to troop strength; and the currency control program was fast becoming a disaster. The modest favorable balances produced by the currency control books in December and January evaporated in February when the troops sent home $10 million more than they received in pay. Thereafter the movement was all downhill as $14 million more went out than came into the theater in March, $17 million each month in April and May, and $18 million in June. The British, in March, went to military scrip, which was not convertible into marks, and the War Department and USFET were considering doing the same in the U.S. zone but were concerned about the effects on commands stationed in other areas and troublesome reactions from the Soviet Union.75 The clearest symbol of the change from wartime to occupation status was the opening on 1 March in Giessen of the first military community to house military dependents and U.S. civilians, as the directive read, "in a manner comparable to that on U.S. posts in 1937." 76 USFET expected eventually to have 90,000 dependents ac-

[442]

commodated in ninety-seven communities, providing PX's, commissaries, barbershops, beauty parlors, dispensaries, and houses and apartments requisitioned from the Germans. The first special dependents' train arrived from Bremerhaven on 10 May.77 Between 1 June and 1 July, Third Army entered the final phase of the ground forces reorganization and conversion to the police-type occupation. The U.S. Constabulary became operational in an on-the-job training status because three-fourths of the enlisted men were recent arrivals and the three-division tactical force moved into permanent stations and began training as a tactical and limited strategic reserve.78

Army-administered military government would continue in Germany for another three years, the occupation for nine years, and the U.S. military presence for a generation or more; nevertheless, the month of June 1946 marked the crossing of a major divide. Behind lay two world wars and a trail of by then meaningless ambitions and anxieties. The future was far from certain, but one thing was apparent: it would not be anything like what had been expected a year ago or less. The world had changed, Germany had changed, and the rationale of the occupation had changed. The troops who had imposed the Allied will on the conquered country had gone home, as had all but a few of the military government officers and men who had accompanied them. The Morgenthau Plan was an embarrassing memory. JCS 1067 continued as the statement of U.S. policy, as much as for any other reason, because no one wanted to tackle the job of organizing the jigsaw pieces of subsequent policy and practice into a new directive.79 The United States was committed to reconstruction, currency reform, and economic reunification in Germany; and to accomplish these goals, Clay would offer, on 20 July 1946 in the Control Council, to enter into agreements with any or all of the other occupying powers. Secretary of State Byrnes would make the same offer publicly in Stuttgart in September. U.S. policy had come full circle. FM 27-5, in its first version, had advocated making friends out of former enemies. JCS 1067 had wanted brought home to the Germans that "Germany's ruthless warfare and fanatical Nazi resistance have destroyed the German economy and made chaos and suffering inevitable." 80 Byrnes, speaking to Germans in Stuttgart, said, "The American people want to help the German people win their way back to an honorable place among the free and peace-loving peoples of the world." 81

[443]

Return to the Table of Contents