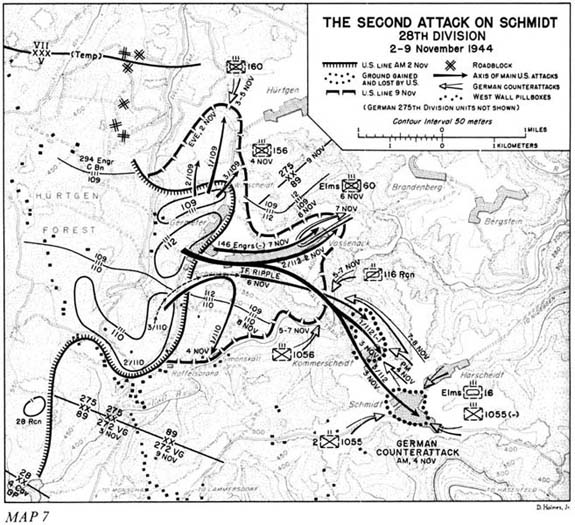

CHAPTER XV The Second Attack on Schmidt As October neared an end, Genera Hodges set a tentative target date of 5 November for renewal of the First Army's big push to the Roer and the Rhine Additional divisions soon were to arrive to bolster the front. The Ninth Army was reorganizing hastily in the old XIX Corps zone, preparing to share responsibility for the coming offensive. The divisions near Aachen brought in replacements and readjusted their lines. The critical shortage of artillery ammunition was easing as stockpiles grew.1 [341] into the corridor, the armor was to drive northeast from the vicinity of Monschau. Thus the stubborn West Wall positions in the Monschau Corridor, which had defied the 9th Division in September, would be hit by a double assault, front and rear.2

Again as American commanders readied an attack on Schmidt, they made no specific plans for the objective which was in reality the ripest fruit that could be plucked as a corollary of an attack on Schmidt the Roer River Dams. (See Map 5) Even though the First Army drive which was to follow the preliminary thrust might be punished severely should the Germans make tactical use of the waters of the Roer reservoirs, neither the V Corps nor the First Army made any recorded plans for continuing the attack beyond Schmidt to gain the dams. The commander of the regiment that made the main effort of this second drive on Schmidt said later that the Roer River Dams "never entered the picture."3 This is not to say that the Americans were totally unaware of the importance of the dams. After the war, General Bradley noted, "It might not show in the record, but we did plenty of talking about the dams."4 Earlier in the month of October the V Corps staff had studied the dams, and on 27 October the V Corps engineer had warned it would be "unwise" for American forces to become involved beyond the Roer at any point below the Schwammenauel Dam before that dam was in American hands.5 Nevertheless, not until 7 November, six days after start of the second attack on Schmidt, was the First Army to call for any plan to seize the dams. On that date, General Hodges' chief of staff, General Kean, told the V Corps to prepare plans for future operations, one of which would be "in the event First Army is ordered to capture and secure the [Schwammenauel] dam ......."6 Even as late as 7 November, General Hodges apparently had no intention of ordering an attack to the dams on his own initiative. All signs seemed to indicate that American commanders still did not appreciate fully the tremendous value of the dams to the enemy. As late as 6 November, for example, one of the divisions that would have to cross the Roer downstream from the dams assumed the Germans would not flood the Roer because it might hinder movement of their own forces.7 [342] Though General Gerow seemingly had no plans in regard to the Roer River Dams, he chose nevertheless to reinforce the 28th Division strongly for the attack. [343] The problem facing General Cota was how best to use such limited freedom as was left him in trying to circumvent three obstacles which always exercise heavy influence on military operations but which promised to affect the attack on Schmidt to an even greater extent than usual. These were: terrain, weather, and enemy. The overbearing factor about the terrain in this region is its startlingly assertive nature. Ridges, valleys, and gorges are sharply defined. The Roer and subsidiary stream lines, including the little Kall River, which cut a deep swath diagonally across the 28th Division's zone of attack, slice this sector into three distinct ridges. In the center is the Germeter Vossenack ridge. On the northeast is the Brandenberg Bergstein ridge, which gives the impression to the man on the ground of dominating the Vossenack ridge. Except for temporary periods of neutralization by [344] artillery fire, the 28th Division would have to operate through the course of its attack under observation from the Brandenberg Bergstein ridge. The third ridge line runs between the Kall and the Roer, from the Monschau Corridor through Schmidt to the Roer near Nideggen. A spur juts out northwestward from Schmidt to Kommerscheidt. Because this ridge represents the highest elevation west of the Roer, the 28th Division would be under dominant enemy observation all the way to Schmidt.

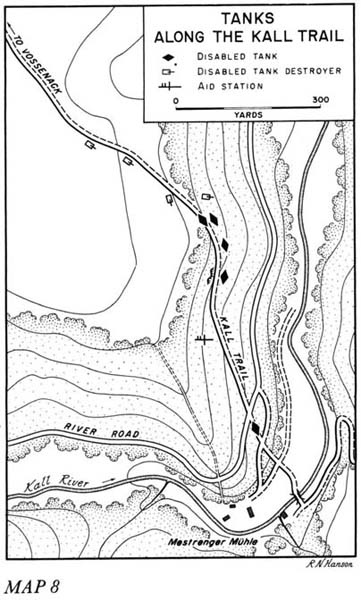

Though the 9th Division had pierced the Huertgen Forest to the Germeter-Vossenack clearing, the 28th Division still would be enmeshed among the thick firs and undergrowth. Both the regiment attacking north from Germeter to gain the woods line overlooking Huertgen and the regiment attacking south through Raffelsbrand would have to fight in the forest. The regiment making the main effort toward Schmidt would pass in and out of the woods. Along the route to be taken the trees hugged the lines of the streams for about 600 yards on either side, while the ridges were bald. Along the bald high ground ran the roads. A dirt road linked Germeter and Vossenack. From Vossenack to the southeast, the map showed a narrow cart track dropping precipitously to the Kall River, then rising tortuously to Kommerscheidt and along the spur to Schmidt. Through Schmidt passes a highway linking the Monschau Corridor to Nideggen and another leading downhill to Hasenfeld and the Schwammenauel Dam. General Cota could only hope that the cart track across the Kall, which had to serve as a main supply route, would prove negotiable: on aerial photographs parts of the track did not show up. (Map 8) He also could do little but hope for the best in regard to those places where the track crossed the exposed Vossenack ridge and the bald spur leading to Schmidt. The factor of weather assumed tyrannical proportions, primarily because of the problem of getting tanks across the Kall gorge from Vossenack to Schmidt. Rain obviously would lessen chances of traversing the treacherous cart track across the Kall gorge, but more important still, rain would mean grounded aircraft. This might prove calamitous, for the planes had a big assignment. They were to isolate the battlefield to prevent the Germans from committing tanks and other reserves particularly in the crucial zone beyond [345] the Kall River where American tanks probably could not go.

Even assurance of fair weather would not have afforded peace of mind to the airmen. Few could cite an example where air power had been able to isolate such a small battlefield. In this instance, isolation would require destruction of bridges spanning the Roer, and bridges are difficult targets for planes. To compound the problem, the weather augury was anything but encouraging. In considering the enemy, General Cota must have noted with some alarm that his would be the only U.S. attack along more than 170 miles of front, from the thumbshaped corridor west of the Maas beyond Roermond all the way south to the Third Army near Metz. Whereas the 28th Division G-2 estimated the enemy had little more than 5,000 troops facing the division, these already had proved their mettle against the 9th Division. Although the same grab bag assortment under General Schmidt's 275th Division that had opposed the earlier attack still held the front, nothing in the 9th Division's experience showed that the slackness of the enemy's organization appreciably lessened the vigor of his defense. Indeed, the 275th Division's organization of the various Kampfgruppen under three regiments the 983d, 984th, and 985th had been progressing steadily. The 275th Division remained a part of General Straube's LXXIV Corps under General Brandenberger's Seventh Army. Although intelligence officers long had known that the 89th Infantry Division held the line farther south in the Monschau Corridor, they had not ascertained that a date for relief of the 89th by a volks grenadier division was fast approaching. The 89th's relief might provide a reserve close at hand to influence the battle for Schmidt. As the 28th Division moved into the Huertgen Forest, the Germans knew an attack was imminent. They had identified the division, though they had failed to detect the shift in boundaries that had assigned this sector to the V Corps. One thing the Germans recognized now without question: the importance of the Vossenack Schmidt sector. Not only did it represent the key to the Roer River Dams; by holding its dominating ridges, the Germans also might forestall any threat to the road and communications center of Dueren while at the same time keeping the Americans bottled up in the Huertgen Forest. Those officers near the top of the German ladder of command recognized also that loss of Vossenack and Schmidt would pose a serious threat to plans already under way for a counteroffensive in the Ardennes.11 Unaware of the full value of Schmidt to the enemy, General Cota nevertheless did not like the idea of splitting his division in cruel terrain on three divergent missions. Moving with his men into the former 9th Division positions on 26 October did nothing to help matters. They found themselves in a dismal forest of the type immortalized in old German folk tales. All about them they saw emergency rations containers,. artillery stripped trees, loose mines along muddy firebreaks and trails, and shell and mine craters by the hundreds. The troops they relieved were tired, dirty, unshaven, and nervous. [346] Everywhere the forest scowled wet, cold, and seemingly impenetrable.

By 29 October General Cota was ready to enunciate his plan. The attack was to open with a preliminary thrust northward by the 109th Infantry (Lt. Col. Daniel B. Strickler). Attacking through Wittscheidt and across the same wooded terrain that earlier had seen defeat of Colonel Wegelein's counterattack, the 109th Infantry was to advance about a mile to gain the woods line on either side of the Germeter Huertgen highway overlooking Huertgen. From that point the regiment was to prevent any repetition of Colonel Wegelein's counterattack. Meanwhile, a battalion of the 112th Infantry (Lt. Col. Carl L. Peterson) was to attack from Germeter through Vossenack to occupy the northeastern nose of the Vossenack ridge. From here this battalion was to help protect the division's north flank. Subsequently, at H plus three hours, the remainder of the 112th Infantry was to drive for the main objective. Passing through the road junction at Richelskaul, the bulk of Colonel Peterson's regiment was to move cross country through the woods south of the Vossenack ridge, ford the Kali River, seize Kommerscheidt, then move on to Schmidt a total advance of more than three miles. Coincident with this main effort, the 110th Infantry (Colonel Seely) was to attack southward to take a nest of pillboxes at Raffelsbrand and be prepared to continue on order southward into the Monschau Corridor. Colonel Seely was to withhold one of his battalions from offensive assignment to provide the division commander a small infantry reserve. Reflecting concern about counterattack from the direction of Huertgen, artillery units planned the bulk of their concentrations along the north flank. Except for one company of tanks to assist the 112th Infantry in the attack on Vossenack, attached tanks and self propelled tank destroyers were to augment division artillery fires. Of the supporting engineers, one battalion was to assist the 112th Infantry by working on the precipitous cart track across the Kali gorge, another was to support the 110th Infantry in the woods south of Germeter, and the third was to work on supply trails in the forest west of Germeter. During the planning, General Cota charged the engineers specifically with providing security for the Kali River crossing. Because both ends of the gorge led into German held territory and no infantry would be in a position to block the gorge, this was an important assignment. Nevertheless, as it appeared in the final engineer plan, the assignment was one of providing merely local security.12 North of the 28th Division, engineers of the 294th Engineer Combat Battalion had taken over the job of holding roadblocks in the Huertgen Forest generally along the Weisser Weh Creek. Southwest of the 28th Division's main positions, the division reconnaissance troop screened within the forest and patrolled to positions of the 4th Cavalry Group along the face of the Monschau Corridor. After advancing the target date for the attack one day to V October, General Gerow had to postpone it because of rain, fog, and mist that showed no sign of abatement. This was a matter of serious concern in view of the vital role planned for air support in the 28th Division's attack; yet by the terms of the First [347] Army's original directive, the attack had to be made by 2 November, regardless of the weather. Much of the reason behind this stipulation the hope that the 28th Division's attack might divert enemy reserves from the main First Army drive, scheduled to begin on 5 November-ceased to exist on 1 November when the main drive was postponed five days. Yet General Hodges, the army commander, apparently saw no reason to change the original directive. The 28th Division was to attack the next day, no matter what the state of the weather. H Hour was 0900, 2 November.13

The weather on 2 November was bad. As the big artillery pieces began to fire an hour before the jump off, the morning was cold and misty. Even the most optimistic could not hope for planes before noon. The squadrons actually got into the fight no sooner than midafternoon, and then the weather forced cancellation of two out of five group missions and vectoring of two others far afield in search of targets of opportunity. Perhaps the most notable air action of the day was a mistaken bombing of an American artillery position in which seven were killed and seventeen wounded. Though mist limited ground observation also, both V Corps and VII Corps artillery poured more than 4,000 rounds into the preliminary barrage. Fifteen minutes before the ground attack, direct support artillery shifted to targets in the immediate sector. By H Hour the 28th Division artillery had fired 7,313 rounds. At 0900 men of the 109th Infantry clambered from their foxholes to launch the northward phase of the operation. Harassed more by problems of control in the thick forest than by resistance, the battalion west of the Germeter Huertgen highway by early afternoon had reached the woods line overlooking Huertgen. Yet, consolidation proved difficult. Everywhere the Germans were close, even in rear of the battalion where they infiltrated quickly to reoccupy their former positions. Advancing along the highway, another battalion had tougher going from the outset. After only a 300 yard advance, scarcely a stone's throw from Wittscheidt, the men encountered a dense antipersonnel mine field. Every effort to find a path through proved fruitless, while German machine guns and mortars drove attached engineers to cover each time they attempted to clear a way. The next day, on 3 November, the battalion along the highway sought to flank the troublesome mine field. This was in progress when about 0730 the Germans struck twice with approximately 200 men each time at the battalion on the other side of the road. Though both counterattacks were driven off, they gave rise to a confusing situation on the American side. Misinterpreting a message from the regimental commander, the battalion near Wittscheidt sent two companies to assist in defeating the counterattacks. As these units became hopelessly enmeshed in the other battalion's fight and the depths of the forest, the day's attempt to outflank the mine field and occupy the other half of the 109th Infantry's woods line objective ended. Though the regimental commander, [348] Colonel Strickler, I still had a reserve, attempts to thwart enemy infiltration behind the front had virtually tied up this battalion already. By evening of 3 November, the mold of the 109th Infantry's position had almost set. The regiment had forged a narrow, mile deep salient up the forested plateau between the Weisser Weh Creek and the Germeter Huertgen highway. But along the creek bed the Germans still held to a comparable salient into American lines. For the next few days, while the men dug deep in frantic efforts to save themselves from incessant tree bursts, Colonel Strickler tried both to eliminate the Weisser Weh countersalient and to take the other half of his objective east of the highway; but to no avail. Every movement served only to increase already alarming casualties and to ensnare the companies and platoons more inextricably in the coils of the forest.

Coincident with the 109th Infantry's move north on 2 November, the 112th Infantry had attacked east from Germeter to gain Vossenack and the northeastern nose of the Vossenack ridge. The 2d Battalion under Lt. Col. Theodore S. Hatzfeld made the attack. The presence of a company of tanks with this battalion clearly demonstrated why the Germans wanted to keep the Americans bottled up in the Huertgen Forest. By early afternoon Colonel Hatzfeld's men had subdued Vossenack and were digging in almost at leisure on the northeastern nose of the ridge, though with the uncomfortable certainty that the enemy was watching from the Brandenberg Bergstein ridge to the northeast and from Kommerscheidt and Schmidt. The 28th Division's main effort began at noon on 2 November in the form of an attack by the two remaining battalions of Colonel Peterson's 112th Infantry. Heading east from Richelskaul to move crosscountry through the woods south of Vossenack and cross the Kall gorge to Kommerscheidt and Schmidt, the lead battalion came immediately under intense small arms fire. For the rest of the day men of the foremost company hugged the ground, unable to advance. Though this was the divisional main effort, Colonel Peterson still did not commit the remainder of this battalion or his third battalion, Neither did he call for tank support nor make more than perfunctory use of supporting artillery. What must have occupied his mind was the ease with which his 2d Battalion had captured Vossenack. Why not follow that battalion, he must have reasoned, and strike for Kommerscheidt and Schmidt from the southeastern tip of Vossenack ridge? At any rate, that was the plan for the next day, 3 November. Even as the 112th Infantry launched this irresolute main effort, Colonel Seely's 110th Infantry had begun a frustrating campaign in the forest farther south. One battalion was to take the pillboxes near Raffelsbrand while another drove through the woods to the east to the village of Simonskall alongside the Kall River. Seizure of these two points would dress the ground for advancing south along two roads into the Monschau Corridor, opening, in the process, a new supply route to Schmidt. If any part of the 28th Division's battleground was gloomier than another, it was this. Except along the narrow ribbons of mud that were firebreaks and trails, only light diffused by dripping branches of fir trees could penetrate to the forest floor. Shelling already had made a debris littered jungle of the floor [349] and left naked yellow gashes on the trunks and branches of the trees. Here opposing lines were within hand grenade range. The Germans waited behind thick entanglements of concertina wire, alive with trip wires, mines, and booby traps. Where they had no pillboxes, they had constructed heavy log emplacements flush with the ground. No sooner had troops of the two attacking battalions risen from their foxholes than a rain of machine gun and mortar fire brought them to earth. After several hours of painful, costly infiltration, one battalion reached the triple concertinas surrounding the pillboxes, but the enemy gave no sign of weakening. In midafternoon, the battalion reeled back, dazed and stricken, to the line of departure. With the other battalion, events went much the same. Platoons got lost; direct shell hits blew up some of the satchel charges and killed the men who were carrying them; and all communications failed except for spasmodic reception over little SCR 536's. The chatter of machine guns and crash of artillery and mortars kept frightened, forest blind infantrymen close to the earth. In late afternoon, the decimated units slid back to the line of departure. The 110th Infantry obviously needed direct fire support. Though the 9th Division's 60th Infantry had used tanks to advantage in the woods about Raffelsbrand, Colonel Seely bowed to the density of the woods, the dearth of negotiable roads, and the plethora of mines. Again on 3 November the infantry attacked alone. If anything, this second day's attack proved more costly and less rewarding than the first. One company fell back to the line of departure with but forty two men remaining. Failure of this second attack and more favorable developments in the 112th Infantry's main effort prompted General Cota in early evening of 3 November to release Colonel Seely's remaining battalion, the one he had earmarked as division reserve. Before daylight on 4 November, this battalion was to move to Vossenack and then drive due south into the woods to Simonskall. This might bring control of one of the 110th Infantry's assigned objectives while at the same time creating a threat to the rear of the pillboxes at Raffelsbrand. What had to be chanced in this decision was the possibility that after commitment of this reserve before dawn, something disastrous might happen elsewhere in the division zone say, at daylight on 4 November, perhaps at Schmidt. [350] had crossed the Kall gorge, and not until after midnight did the infantry have any antitank defense other than organic bazookas. At midnight a supply train of three weasels got forward with rations, ammunition, and sixty antitank mines. These mines the men placed on the three hard surfaced roads leading into the village. Weary from the day's advance, the men made no effort either to dig in the mines or to camouflage them.

The other battalion of the 112th Infantry, commanded by Maj. Robert T. Hazlett, had in the meantime followed Colonel Flood's battalion as far as Komerscheidt. Because Major Hazlett had left one company to defend an original position far back at Richelskaul, he had but two companies and his heavy weapons support. These he split between Kornmerscheidt and a support position at the woods line where the Kali trail emerges from the gorge. Major Hazlett's battalion was to have joined Colonel Flood's in Schmidt, but the regimental commander, Colonel Peterson, had decided instead to effect a defense in depth in deference to his regiment's exposed salient. General Cota must have approved, for he recorded no protest.14 Because inclement weather on 3 November again had denied all but a modicum of air support, the need of getting armor across the Kali gorge to Schmidt grew more urgent. The spotlight in the 28th Division's fight began to settle on the precipitous trail leading through the gorge. An erroneous report prevalent in Vossenack during most of the day of 3 November that the bridge spanning the Kali had been demolished served to discourage any real attempt to negotiate the trail until late in the afternoon. After two engineer officers reconnoitered and gave the lie to this report, a company of tanks of the 707th Tank Battalion under Capt. Bruce M. Hostrup made ready to try it. The trail, the engineer officers said, was a narrow shelf, limited abruptly on one side by a dirt wall studded with rock obstructions and on the other by a sheer drop. A weasel abandoned on the trail by a medical unit blocked passage, but once this was removed tanks might pass by hugging the dirt bank. At the Kali itself, a stone arch bridge was in good condition. In gathering darkness, Captain Hostrup left the bulk of his tanks near the point where the Kali trail enters the woods, while he himself continued in his command tank to reconnoiter. About a quarter of the way from the woods line to the river, the trail became narrow and slippery. The left shoulder, which drops sharply toward the gorge, began to give way under weight of the tank. The rock obstructions in the dirt wall on the other side denied movement off to the right. The tank slipped and almost plunged off the left bank into the gorge. Returning to the rest of his company, Captain Hostrup reported the trail still impassable. His battalion commander, Lt. Col. Richard W. Ripple, radioed that the engineers were to work on the trail through the night and that Captain Hostrup's tanks were to be ready to move through to Schmidt at dawn. Under no apparent pressure except to get the trail open by daylight on 4 November, the 20th Engineer Combat Battalion, which was assigned to support the 112th Infantry, made a notably small outlay for [351] a job of such importance. Only two platoons worked on the trail west of the river and but one on the east. Because no one during the original planning had believed that vehicles could get as far as the Kall, the engineers had with them only hand tools. Not until about 0230 in the morning did a bulldozer and an air compressor reach the work site. The bulldozer proved of little value; after about an hour's work, it broke a cable. The only vehicular traffic to cross the Kall during the night was the three weasel supply train which carried the antitank mines to Schmidt.

Despite failure of tanks to cross the Kall and no evidence of clearing weather, the map in the 28th Division's war room on the night of 3 November showed that prospects were surprisingly good. While Colonel Strickler's 109th Infantry had attained only half its objective, the regiment nevertheless was in position to thwart counterattack from Huertgen. By commitment of the reserve battalion of the 110th Infantry before daylight to seize Simonskall, stalemate in the woods south of Germeter might be broken. Enemy units encountered were about what everyone had expected: the three regiments of the 275th Division, representing, in fact, consolidations of numerous Kampfgruppen. Albeit the weather had limited observation, no one yet had spotted any enemy armor. Most encouraging of all, the 28th Division had two battalions beyond the Kall, one in Kornmerscheidt and the other astride the division objective in Schmidt. Capture of Schmidt meant that the main supply route to the German forts in the Monschau Corridor was cut. The Germans would have to strike hard and soon or the 28th Division would be in shape to start a push into the corridor. Division and corps commanders all along the front had begun to telephone their congratulations to General Cota, so that despite his reservations he was beginning to feel like "a little Napoleon."15 Had General Cota and his staff considered two facts about the enemy, one of which they did have at hand, no one in the 28th Division could have slept that night, no matter what the elation over capture of Schmidt. First, the relief from the line in the Monschau Corridor of the 89th Infantry Division by the 272d Volks Grenadier Division had begun on 3 November. Indeed, when the first of Colonel Flood's troops had entered Schmidt, two battalions of the 89th Division's 1055th Regiment had just passed through going northeast. They stopped for the night between Schmidt and the village of Harscheidt, less than a mile northeast of Schmidt. The remaining battalion of the 1055th Regiment found upon nearing Schmidt after midnight that the Americans had cut the route of withdrawal. This battalion dug in astride the Schmidt-Lammersdorf road just west of Schmidt. A little patrolling by Colonel Flood's battalion might have revealed the presence of this enemy regiment deployed almost in a circle about Schmidt. Even without patrols, the 28th Division might have been alert to the likely presence of the 89th Division, for during the day of 3 November other units of the V Corps had taken prisoners who reported the division's relief. This information had [352] reached the 28th Division during the day.16 The second fortuitous occurrence on the enemy side had as far reaching effects for the Germans as the other. At almost the same moment that the 28th Division attacked at H Hour on 2 November, staff officers and commanders of Army Group B, the Fifth Panzer and Seventh Armies, and several corps and divisions, including the LXXIV Corps, were convening in a castle near Cologne. There the Army Group B commander, Field Marshal Model, was to conduct a map exercise. The subject of the exercise was a theoretical American attack along the boundary of the Fifth Panzer and Seventh Armies in the vicinity of Huertgen. The meeting had been in session only a short time when a telephone call from the LXXIV Corps chief of staff told of the actual American attack. The situation, the chief of staff said, was critical: the LXXIV Corps had not enough men even to plug the gaps already opened; Seventh Army would have to send reserves. Directing the LXXIV Corps commander, General Straube, to return to his post, Field Marshal Model told the other officers to continue the map exercise with the actual situation as subject. Continuing reports of further American advances then prompted a decision to send a small reserve to General Straube's assistance. A Kampfgruppe of the old warhorse, the 116th Panzer Division, was to leave immediately to assist local reserves in a counterattack against the 109th Infantry's penetration north of Germeter. Like the counterattack Colonel Wegelein had tried against the 9th Division, this was designed to push through to Richelskaul and cut off that part of the 112th Infantry which had penetrated into Vossenack. Without a doubt, chance presence of the various major commanders at the map exercise facilitated German reaction against the 28th Division's attack. [353] Division's 1055th Regiment were to counterattack at both Schmidt and Kommerscheidt. At the same time Waldenburg's 60th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, en route to Huertgen, was to launch a new counterattack after the old plan against the 109th Infantry. [354] eled at night, neither armor nor infantry had encountered American planes and were arriving in good shape.17 Before daylight on 4 November, two events were happening on the American side that were to bear heavily on the outcome of the day's action. First, General Cota was committing his only infantry reserve, a battalion of the 110th Infantry, to drive south from Vossenack through the woods to Simonskall in an effort to turn the stiff enemy line at Raffelsbrand. Launched before dawn, the attack met negligible resistance. By 0900 the battalion had seized Simonskall, a commendable success but one which failed to weaken resistance at Raffelsbrand and served to occupy the only infantry reserve which General Cota might have used as the day's events developed. Second, after a somewhat feeble effort by attached engineers through most of the night to improve the Kali trail, tank crewmen under Captain Hostrup warmed their motors an hour or so before daylight for another try at crossing the Kali. The lead tank under 1st Lt. Raymond E. Fleig had just entered the woods along the slippery Kali trail when it struck a mine. A track disabled, the tank partially blocked the trail. By using a winch, the tankers finally got four tanks past. Lieutenant Fleig then boarded the lead tank and by tortuous backing and turning finally reached the Kali to begin the toilsome last lap to Kommerscheidt just as day was breaking. Behind him Fleig left the shoulder of the trail torn and crumbling. Only with the utmost difficulty and caution did the remaining three tanks of his platoon make their way. The tankers encountered a particular problem at one point where a giant outcropping of rock made it impossible to hug the right side of the trail. Near the bottom of the gorge, the last of the three tanks stuck in the mud and threw a track. Only two tanks now were following Lieutenant Fleig's toward Kommerscheidt. Trying to maneuver the rest of the tank company across the Kali, Captain Hostrup first met difficulty at the tank which Lieutenant Fleig had abandoned after hitting a mine. Here one tank in attempting to pass plunged off the left shoulder of the trail. Using the wrecked tank as a buffer, two more tanks inched past; but near the rock outcropping both these slipped off the trail and threw their tracks. As battle noises from the direction of Schmidt began to penetrate to the gorge, three tanks under Lieutenant Fleig were beyond the river on the way to Kommerscheidt; but behind them, full on the vital trail, sat five disabled tanks. Not even the dexterous weasels could slip through. In Schmidt, as daylight came about 0730 on 4 November, the crash of a German artillery barrage brought Colonel Flood's battalion of the 112th Infantry to the alert. About half an hour later the peripheral outposts shouted that German tanks and infantry were forming up in the fringe of Harscheidt. For some unexplained reason, American artillery was slow to respond; not until 0850 did the big guns begin to deliver really effective defensive fires. By that time the fight was on in earnest. Infantrymen from the battalion of the 1055th, Regiment [355] KALL TRAIL, showing the Konimerscheidt side of the gorge in the background. that had found their route of withdrawal cut by American capture of Schmidt charged in from the west. The other two battalions of the regiment and at least ten tanks and assault guns of the 16th Panzer Regiment struck from the direction of Harscheidt.18 As the German tanks clanked methodically onward in apparent disdain of the exposed mines strung across the hard-surfaced roads, the defenders opened fire with bazookas. At least one scored a hit, but the rocket bounced off. The German tanks came on, firing their big cannon and machine guns directly into foxholes and buildings. Reaching the antitank mines, the tanks merely swung off the roads in quick detours, then waddled on. Such seeming immunity to the bazookas and mines [356] Confusion mounted. As rumor hummed about that orders had come to withdraw, individually and in small groups those American infantrymen still alive and uncrippled pulled out. The overwhelming impulse to get out of the path of the tanks sent the men streaming from the village in a sauve qui Peut. About 200 fled into the woods southwest of Schmidt, there to find they actually were deeper in German territory. The others tore back toward Kommerscheidt. The dead lay unattended. Because the battalion's medical aid station had not advanced any farther than a log walled dugout beside the Kall trail west of the river, the only comfort for the wounded was the presence of company aid men who volunteered to stay with them.

By 1100 most Americans who were to get out of Schmidt had done so. By 1230 the 28th Division headquarters apparently recognized the loss, for at that time the first air support mission of the day struck the village. For the third straight day fog and mist had denied large scale air support. No more solid proof than the German attack on Schmidt was needed to show that the attempt to isolate the battlefield had failed. In Kommerscheidt and at the Kall woods line several hundred yards north of Kommerscheidt, the men of Major Hazlett's understrength battalion of the 112th Infantry were exposed fully to the sounds of battle emanating from Schmidt. By midmorning small groups of frightened, disorganized men began to filter back with stories that "they're throwing everything they've got at us." By 1030 the numbers had reached the proportions of a demoralized mob, reluctant to respond to orders. Some men wandered back across the Kall to Vossenack and Germeter. Yet within the mass a few frantic efforts to stem the withdrawal had effect. When the enemy did not pursue his advantage immediately, groups of Colonel Flood's men began to reorganize and dig in with Major Hazlett's. About 200 joined the Kommerscheidt defenses. Despite air attacks against Schmidt and round after round of artillery fire poured into the village, the reprieve from German tanks and infantry did not last long. In early afternoon a posse of at least five Mark IV and V tanks and about 150 infantry attacked. Imitating the tactics they had used at Schmidt, the enemy tankers stood out of effective bazooka range and pumped shells into foxholes and buildings. The day might have been lost save for the fact that Major Hazlett had an ace which Colonel Flood had not had in Schmidt. He had Lieutenant Fleig's three tanks. From right to left of the position Fleig and his tanks maneuvered fearlessly. Spotting a Mark V Panther overrunning positions in an orchard on the eastern fringe of Kommerscheidt, Lieutenant Fleig directed his driver there. Although the lieutenant got in the first shots, his high explosive ammunition bounced off the Panther's tough hide. All his armor piercing rounds, Fleig discovered, were outside in the sponson rack. When Fleig turned his turret to get at these rounds, the Panther opened fire. The first shot missed. Working feverishly, the lieutenant and his crew thrust one of the armor piercing rounds into the chamber. The first shot cut the barrel of the German gun. Three more in quick succession tore open the left side of the Panther's hull and set the tank afire. By 1600 the Germans had begun to fall back, leaving behind the hulks of five [357] tanks. A bomb from a P-47 had knocked out one, a bazooka had accounted for another, and Lieutenant Fleig and his tankers had gotten three. The presence of the lieutenant and his three tanks obviously provided a backbone to the defense at Kommerscheidt that earlier had been lacking at Schmidt.

In midafternoon General Cota ordered that the units in Kommerscheidt attack to retake Schmidt, but no one on the ground apparently entertained any illusions about immediate compliance. When the regimental commander, Colonel Peterson, and the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. George A. Davis, arrived in late afternoon to survey the situation, they must have realized that the question was not of retaking Schmidt but of holding Kommerscheidt. As the men on the ground soon came to know, it was a difficult position to hold, situated as it was under direct observation from the higher part of the Schmidt Kommerscheidt spur and from the Brandenberg-Bergstein ridge. Not all the day's events brought on by entry of German reserves took place beyond the Kall. No one, for example, was more conscious of major additions to enemy artillery strength than the men of Colonel Hatzfeld's battalion of the 112th Infantry on the bald Vossenack ridge. Both Army Group B and Seventh Army had sent several artillery, assault gun, antitank, and mortar battalions to the sector, and General Straube committed a portion of the artillery and antitank guns of the three of his LXXIV Corps divisions not affected by the American attack.19 Subject as Colonel Hatzfeld's troops were to dominant observation from the Brandenberg Bergstein ridge, they found it worth a man's life to move from his foxhole during daylight. Even if he stayed he might be entombed by shellfire. The companies began to bring as many men as possible into the houses during the day, leaving only a skeleton force on the ridge. Still casualties mounted. In the western end of Vossenack, troops carried on their duties while traffic continued to flow in and out of the village. Someone entering Vossenack for only a short time, perhaps during one of the inevitable lulls in the shelling, might not have considered the fire particularly effective. But the foot soldiers knew differently. To them in their exposed foxholes, a lull was only a time of apprehensive waiting for the next bursts. The cumulative effect began to tell. [358] Division on three sides. In and south of the Monschau Corridor, continuing relief by the 272d Volks Grenadier Division made available the 89th Division's second regiment, the 1056th. The 89th Division commander, Generalmajor Walter Bruns, ordered the 1056th Regiment into the woods to hold a line between Simonskall and the 1055th Regiment, which was attacking Kommerscheidt.20 Also during the day of 4 November, the remaining regiment of the 116th Panzer Division, the 156th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, arrived at Huertgen. The division commander, General von Waldenburg, ordered the regiment into the woods north and northeast of Vossenack. He told attached engineers to build a road through the woods so that tanks might assist the panzer grenadiers in taking Vossenack, though eventually he had to abandon this venture.21

As ordered by the Seventh Army commander, General Brandenberger, German plans to restore the situation which had existed on the opening day of the American offensive now were definitely formulated. The 275th Division was to ensure that the wings of the American salient were held against further widening. Renewing the attack against Kornmerscheidt on 5 November, General Bruns's 89th Division was to clear the east bank of the Kall with the assistance of the bulk of the 16th Panzer Regiment. Continuing to punch at the 109th Infantry with one panzer grenadier regiment, General von Waldenburg was to maneuver the rest of the 116th Panzer Division into position for a concentric attack on Vossenack. Both to gain a position from which to assist the attack on Vossenack from the south and also to cut off the Americans in Kommerscheidt, the 116th Panzer Division's Reconnaissance Battalion was to drive on 5 November down the Kall gorge from the northeast to effect a link with the 89th Division. The Germans did not realize that the 28th Division had taken virtually no defensive measures in the Kall gorge.22 Although the spotlight from the American side was focused on the Kall gorge, the 28th Division was concentrating not on defending the gorge but on getting the precarious Kall trail open so that armor might cross to Kommerscheidt. Only three weasels and three tanks had crossed the Kall, and five disabled tanks now blocked the way. Despite the urgency of opening the trail, only a company and a platoon of engineers worked there during 4 November. For fear of damaging the disabled tanks, the engineers hesitated to use explosives on the main obstacle, the giant outcropping of rock. Indeed, everybody appeared to treat the disabled tanks with the kind of warm hearted affection an old time cavalryman might lavish on his horse. Why not sacrifice the five disabled tanks by pushing them off the trail into the gorge? This tank company under Captain Hostrup still had six more tanks, and the 28th Division had two other companies of tanks and almost a battalion of self propelled tank destroyers available to cross the Kall. Yet all [359] through the day of 4 November and far past midnight the tankers worked at the frustrating task of righting the tracks on the tanks, inching the vehicles forward a few paces, and watching the tracks jump off again.

Part reason for dalliance no doubt lay in the fact that General Cota all day long was ill informed about the condition of his vital main supply route across the Kall. Most reports reaching 28th Division headquarters repeatedly asserted that the trail was open. Neither the 112th Infantry nor General Cota had liaison officers on the spot. Not until approximately 0230, 5 November, did the tankers desist in their admirable but illogical struggle to save their tanks. At that time General Cota gave them a direct order either to have the trail clear by daybreak or to roll the immobilized tanks down the slope. As the engineers blew the troublesome rock outcropping, the tankers threw all their vehicles off the trail except the one stuck in the mud near the bottom of the gorge. That one might be bypassed, someone had discovered, by following a circuitous cutoff provided by two smaller trails. The first vehicular traffic to cross the Kall after removal of the tanks was a convoy of 5 weasels carrying rations and ammunition. Later, soon after daylight on 5 November, 9 self propelled MIO tank destroyers of the 893d Tank Destroyer Battalion and the 6 remaining tanks of Captain Hostrup's company crossed the river. By noon of 5 November the Americans had 9 tanks and 9 tank destroyers east of the Kall. They needed these and more. Even before the first of these reinforcements arrived, the Germans struck again at Kommerscheidt. Weak from cold, rain, and fatigue, the remnants of the two battalions of the 112th Infantry had no recourse but to huddle miserably in their foxholes, awaiting whatever the Germans might throw at them. Enemy observation from Schmidt was so damaging that men dared not emerge from their holes, even for sanitary reasons. As everywhere in the 28th Division sector, casualties from combat fatigue and trench foot were on the rise. The only real comfort the infantrymen had was the knowledge that their artillery was punishing the Germans with "terrific" fires. Lieutenant Fleig and his three veteran tanks saved the day against the first German attack soon after dawn on 5 November. When they immobilized one of five enemy tanks, the others gradually withdrew. Although the Germans made several more strikes during the day, their tanks participated only by fire from covered positions in Schmidt. No doubt they hesitated to emerge because for the first time since the offensive had begun, American planes had good hunting. Clearing weather permitted the first planes to take to the air as early as 0835 and remain out all day. The pilots claimed at least 10 enemy armored vehicles destroyed, but only 2 or 3 of these at Schmidt.23 In the meantime, the Germans had taken up arms against another group of [360] American infantrymen whose detailed story may never be told. These were the men, perhaps as many as 200, who had fled from Schmidt on 4 November into the woods southwest of that village. On 5 November the enemy's I055th Regiment noted the first prisoners from this group. Before dawn on 9 November three from the trapped group were to make their way to American lines but with the report that when they had left two days before to look for help, the remaining men had neither water nor rations. The three men doubted that on 9 November any still survived. They probably were right. The 89th Division reported that on 8 November, after the Americans had held out for four days, the Germans captured 133 Presumably, these were the last.24

A definite pattern in the fighting now had emerged. The battlefields of the 112th Infantry at Kommerscheidt and Vossenack, while separated in locale by the fissure of the Kall gorge, were wedded in urgency. For even as the fight raged at Kommerscheidt, the inexorable pounding of the bald Vossenack ridge by the enemy's artillery went on. Not even presence overhead of American planes appeared to silence German guns. Casualties of all types soared. So shaky was the infantry that the assistant division commander, General Davis, ordered at least a platoon of tanks to stay in Vossenack at all times to bolster infantry morale. Action on the other two battlefields, that of the 109th Infantry on the wooded plateau north of Germeter and of the 110th Infantry to the south at Sinionskall and Raffelsbrand, ebbed and flowed with the fortunes of the center regiment. On 5 November the 109th Infantry held against continued counterattacks by the 60th Panzer Grenadier Regiment. The 110th Infantry made virtually no progress in persistent attempts to close the pillbox-studded gap between the battalions at Sinionskall and Raffelsbrand. Not for some days would the fact be acknowledged officially, but the 110th Infantry already was exhausted beyond the point of effectiveness as a unit. As these events took place on 5 November, another act was about to begin along the Kall trail. When the assistant division commander, General Davis, had traversed the trail the afternoon before en route to Kommerscheidt, he had noted that the engineers had no one defending either the bridge or the trail itself. Encountering a company of the 20th Engineers, General Davis told the commander, Capt. Henry R. Doherty, to assume a defensive position where the trail enters the woods southeast of Vossenack. Captain Doherty was also, General Davis said, to "guard the road near the bridge."25 At the bridge, the engineer officer stationed a security guard of three men under T/4 James A. Kreider, while the remainder of the engineer company dug in at the western woods line. Except for Kreider's small force, the defensive positions chosen were of little value, for a thick expanse of woods separated the engineers from the bridge and from the main part of the Kall trail. The first indication that the Germans might accept the standing invitation to sever the 112th Infantry's main supply route came about midnight on 5 November. Bound for Kommerscheidt, an antitank squad towing a gun with a weasel [361] was attacked without warning near the bottom of the gorge. Even as this ambush occurred, engineers were working on the trail not far away, and two supply columns subsequently crossed the Kall safely.

A few hours later, at approximately 0230 on 6 November, two squads of engineers working on the trail near the bridge decided to dig in to protect themselves against German shelling. As they dug, these two squads and the four man security guard at the bridge represented the only obstacle to uninterrupted German movement along the Kall gorge. The engineers still were digging when a German appeared on the trail some fifteen yards away, blew two shrill blasts on a whistle, and set off a maze of small arms fire. Taken by surprise, the engineers had no chance. Those who survived did so by melting into the woods. At the Kall bridge, Sergeant Kreider and the men of his security guard saw the Germans but dared not fire at such a superior force. Another group of Americans was in the Kall gorge at this time. They were medics and patients who occupied a logwalled dugout alongside the trail halfway up the western bank. The dugout was serving as an aid station for both American battalions in Kommerscheidt. About 0300 several Germans knocked at the door of the dugout. After satisfying themselves that the medics were unarmed, the Germans posted a guard and left. At intervals through the rest of the night, the medics could see the Germans mining the Kall trail. At about 0530, as two jeeps left Vossenack with ammunition for Kornmerscheidt, a platoon of Germans loomed out of the darkness on the open part of the trail southeast of Vossenack. Firing with machine guns and a panzerfaust, the Germans knocked out both jeeps. The lieutenant in one vehicle yelled to an enlisted man riding with him to fire the jeep's machine gun. "I can't, Lieutenant," the man shouted; "I'm dying right here!" These events clearly demonstrated that local security, as enunciated in the engineer plan, was not enough to prevent German movement along the Kall gorge. Indeed, these incidents indicated that the 20th Engineers had an unusual conception of what constituted security. Except at the woods line where Captain Doherty's company held defensive positions, soldiers of the 116th Panzer Division's Reconnaissance Battalion controlled almost every segment of the Kall trail west of the river. Erroneous reports about the status of the supply route through the hours of darkness on the morning of 6 November forestalled any last minute attempt to defend the trail. Not until about 0800 did the engineer group commander, Colonel Daley, get what was apparently accurate information. He immediately ordered the 20th Engineers to "Get every man you have in line fighting. Establish contact with the Infantry on right and left . . . ." No one did anything to comply with the order. By this time another crucial situation arising in Vossenack had altered the picture. The first step taken by the 28th Division to counteract the enemy's intrusion into the Kall gorge actually emerged as a corollary of a move made for another purpose. It had its beginning in late afternoon of 5 November when General Cota announced formation of a special task force under the 707th Tank Battalion commander, Colonel Ripple. Task Force Ripple was to cross the Kall and assist the [362] remnants of the 112th Infantry to retake Schmidt. Thereupon, the task force was to open the second phase of the 28th Division's attack, the drive southwest into the Monschau Corridor.

Task Force Ripple looked impressive on paper. Colonel Ripple was to have a battalion of the 110th Infantry, one of his own medium tank companies and his light tank company, plus a company and a platoon of self propelled tank destroyers. Yet, in reality, Task Force Ripple was feeble. The stupefying fighting in the woods south of Germeter had reduced the infantry battalion to little more than 300 effectives, of which a third were heavy weapons men. The company of medium tanks was that of Captain Hostrup, already in Kommerscheidt but with only nine remaining tanks. The company of tank destroyers was that in Kommerscheidt, reduced now to seven guns. The other platoon of tank destroyers and the company of light tanks still had to cross the mined and blocked Kall trail. So discouraging were prospects of passage that no one ever got around to ordering the light tanks to attempt it. The platoon of tank destroyers contributed to passage of Task Force Ripple across the Kall, though the destroyers themselves never made it. Moving along the open portion of the trail southeast of Vossenack, the destroyers dispersed the Germans who earlier had knocked out the two jeeps with machine guns and panzerfaust. When the depleted infantry battalion arrived at the entrance of the trail into the woods about 0600 on 6 November, the tank destroyer crewmen asked at least a platoon of infantry to accompany their guns down the Kall trail. Colonel Ripple refused. Considering his infantry force already too depleted, he intended to avoid a fight along the trail by taking instead a firebreak paralleling the trail. Almost from the moment the infantry entered the woods at the firebreak, they became embroiled in a small arms fight that lasted all the way to the river. Not until well after daylight did the infantry cross the Kall and not until several hours later did they join Colonel Peterson's troops at the woods line north of Kommerscheidt. In the crossing the battalion lost seventeen men. Yet in getting beyond the Kall, Colonel Ripple in effect had made a successful counterattack against the 116th Panzer Division's Reconnaissance Battalion. The enemy had fallen back along the river to the northeast. Though the Americans did not know until later in the day, the Kall trail as early as 0900 on 6 November was temporarily clear of Germans.26 The scene that Task Force Ripple found upon arrival beyond the Kall was one of misery and desolation. Though one artillery concentration after another prevented German infantry from forming to attack, the enemy's tanks sat on their dominating perch in the edge of Schmidt and poured round after round into Kommerscheidt. Maneuvering on the lower ground about Kommerscheidt, the American tanks and tank destroyers were no match for the Mark IV's and V's.27 By midday on 6 November, only 6 American tanks remained fully operational and only 3 of an original 9 destroyers. The clear weather of the day before had given [363] way to mist and overcast so that the enemy tanks again had little concern about American planes.

After seeing Task Force Ripple's battered infantry battalion, the 112th Infantry commander, Colonel Peterson, could divine scant possibility of success in retaking Schmidt. He nevertheless fully intended to go through with the attack. But as the officers reconnoitered, one adversity followed another. In a matter of minutes the battalion of the 110th Infantry lost its commander, executive officer, S-2, and a company commander. Canceling the proposed attempt to retake Schmidt, Colonel Peterson told the men of the 110th Infantry to dig in along the woods line north of Kornmerscheidt in order to strengthen his defense in depth. The lonely despair of the men east of the Kall by this time must have deepened, for surely they must have heard that the main drive by the VII Corps had been postponed to 11 November and that even this target date was subject to the vagaries of weather. That higher commanders were concerned as evidenced by visits to the 28th Division command post on 5 November by Generals Hodges, Gerow, and Collins was scarcely sufficient balm for the bitter knowledge that theirs would remain for at least five more days the only attack from the Netherlands to Metz. Though dreadful to the men involved, the retreat from Schmidt and the trouble at Kommerscheidt had posed no real threat to the 28th Division's integrity. As dawn came on 6 November, at the same time Task Force Ripple was unwittingly clearing the Germans from the Kall gorge, another crisis was arising that did spell a threat to the very existence of the division. [364] ing equipment, the men raced wild eyed through Vossenack. Circumstances had evoked one of the most awful powers of war, the ability to cast brave men in the role of cowards.

Dashing from the battalion command post near the church in the center of Vossenack, the battalion staff tried frantically to stem the retreat. It was an impossible task. Most men thought only of some nebulous place of refuge called "the rear." By 1030 the officers nevertheless had established a semblance of a line running through the village at the church, but in the line were no more than seventy men. Even as the retreat had begun, a platoon of tank destroyers and a platoon of tanks were in the northeastern edge of Vossenack. Although both stayed there more than a half hour after the infantry pulled out, crewmen of neither platoon saw any German infantry either attacking or attempting to occupy the former American positions. First reports of the flight brought four more platoons of tanks racing from Germeter into the village. Not until midmorning did the last of the tanks leave the eastern half of Vossenack to join the thin olive drab line near the church. On the enemy side, General von Waldenburg's 116th Panzer Division had planned an attack on Vossenack for 0400, 6 November. The 156th Panzer Grenadier Regiment and some portions of the 60th Panzer Grenadiers were to have struck from the woods north and northeast of the village. But something had happened to delay the attack; either the infantry or the supporting artillery was not ready on time. No positive identification of German troops in Vossenack before noon developed. It was safe to assume that the rout of Colonel Hatzfeld's battalion had resulted not from actual ground attack but from fire and threat of attack.28 As the chaotic situation developed in Vossenack, the highest ranking officer on the scene, the assistant division commander, General Davis, found himself torn between two crises: that at Vossenack and that in the Kall gorge. He could not have known at this time that Task Force Ripple's advance through the gorge already had cleared the Germans from the Kall trail. His only hope for a reserve to influence either situation was the 1171st Engineer Combat Group. Despite some contradictory orders and a lack of liaison between General Davis and the engineer commander, Colonel Daley, a pattern of commitment of the engineers as riflemen had emerged by midafternoon of 6 November. Into Vossenack went the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion (minus a company on detached service). To the Kall gorge went the remnants of the 20th Engineers and two companies of the 1340th Engineer Combat Battalion. A third company of the 1340th Engineers remained in support of the 110th Infantry. In the Kall gorge the engineers happily discovered that the Germans had gone. By nightfall a company of the 1340th Engineers was digging in at the Kall bridge while another company and most of what was left of the 20th Engineers assumed Captain Doherty's old positions at the western entrance of the trail into the Kall woods. [365] In Vossenack the two companies of the 146th Engineers were committed so quickly that the men still wore hip boots they had been using on road repair work. They moved immediately to take responsibility for the thin infantry line near the church.29

The crisis in Vossenack had repercussions all the way back to headquarters of the V Corps. Upon first news of the catastrophe, General Gerow hurriedly alerted the 4th Division's 12th Infantry. Beginning that night, the 12th Infantry was to relieve Colonel Strickler's 109th Infantry on the wooded plateau north of Germeter. Upon relief, the 109th Infantry was to be employed only as approved by General Gerow. Even though this regiment had been mutilated in the fight in the woods, freeing it would decrease somewhat the apprehension over the recurring crises within the 28th Division. General Gerow must have recognized that should the Germans push on from Vossenack past Germeter, they would need only a shallow penetration to disrupt the First Army's plans for the main drive to the Roer by the VII Corps. During the night of 6 November both the 146th Engineers and the 156th Panzer Grenadier Regiment laid plans for driving the other out of Vossenack. Both attacks were to begin about 0800.30 As daylight came the Americans started their preparatory artillery barrage first. When the barrage had ended and the two engineer companies moved into the open to attack, German fire began. Although this shelling hit one of the companies severely, both charged forward, one on either side of the village's main street. They had beaten the Germans to the draw. Despite relative unfamiliarity with an attack role and a lack of hand grenades, radios, and mortars, the engineers attacked with enthusiasm and energy.31 Where particularly stubborn resistance formed, a tank platoon advancing along the southeastern fringe of the village went into action. By early evening the engineers in a superior demonstration had cleared the eastern end of Vossenack at a cost to the 116th Panzer Division of at least 150 casualties. A battalion of the 109th Infantry that had been relieved in the woods north of Germeter took over from the engineers. This time the infantry heeded the lesson demonstrated at such a price by Colonel Hatzfeld's battalion and holed up in the village itself rather than on the exposed nose of the ridge. Though patrol clashes and heavy shelling continued, the tempo of fighting at Vossenack gradually slackened. The situation in the Kall gorge was neither so quickly nor so decisively set right. To be sure, events along the trail had taken a turn for the better on 6 [366] November when passage of Task Force Ripple had driven away the enemy's 116th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion and when the 1340th Engineers had moved one company to the Kall bridge and another to the western woods line. Yet even as the engineers dug in, the Germans were planning a new move in the Kall gorge.

Commanded by Capt. Ralph E. Lind, Jr., the engineer company at the Kall bridge had a strength of not quite a hundred men. Splitting his force, Captain Lind put one platoon east of the river and the remainder on the west. About a half hour before midnight on 6 November, the Reconnaissance Battalion began to move back into the gorge. Behind heavy shelling, about a platoon attacked that part of Captain Lind's company west of the river. Some of the engineers left their foxholes to retreat up the hill toward the other engineer positions at the woods line. For the rest of the night the Germans again roamed the Kall gorge almost at will. Unaware of this development, a supply column carrying rations and ammunition to Kornmerscheidt started from Vossenack about midnight. Once the men in the column thought they heard German voices, but no untoward incident occurred. On the return journey, the vehicles were loaded with wounded. Again the column crossed the river successfully but near the western woods line had to abandon two big trucks because of a tree that partially blocked the trail. By daylight on 7 November, the situation along the Kall trail was something of a paradox. The Germans claimed that despite "considerable losses" the 116th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion again had cut the trail and established contact with the 89th Division in the woods to the south.32 Yet an American supply column had crossed and recrossed the Kall during the night. The Americans thought their engineers controlled the trail, but by midmorning of 7 November, the only force in position to do so that of Captain Lind was down to the company commander and five men. The rest of the engineers had melted away into the woods. Upon learning in early afternoon that the engineers had deserted the bridge, the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Truman H. Setliffe, ordered his third company that had been supporting the 110th Infantry to move to the bridge and "stay there." Commanded by Capt. Frank P. Bane, this company moved down the firebreak paralleling the Kall trail, left a platoon near the foot of the firebreak, and then moved to the bridge. Considering his force too small to justify positions on both sides of the river, Captain Bane remained on the west bank and echeloned his squads up the trail to the west. They made no effort to contact the infantry forces east of the Kall. Thus only a portion of the Kall trail west of the river was secure. One more effort on 7 November to get a firm grip on the elusive Kall trail emerged as a corollary to another commendable but feeble plan to retake Schmidt. Banking on a battalion of the newly relieved 109th Infantry as the main component, General Cota ordered formation of another task force under the assistant division commander, General [367] Davis, to recapture Schmidt. As had Task Force Ripple, Task Force Davis looked impressive on paper. In addition to the battalion of the 109th Infantry, General Davis was to have the 112th Infantry (minus Colonel Hatzfeld's destroyed battalion), the battalion of the 110th Infantry that had gone to Kommerscheidt as a part of Task Force Ripple, two companies of tanks, and two companies of self propelled tank destroyers. Of this force only the battalion of the 109th Infantry in reality had any offensive potential, and that based primarily upon arrival of green replacements the night before. Half of the armor still would have to cross the perilous Kall trail. Four of the tank destroyers tried that in early afternoon of 7 November, only to wreck on the open ridge southeast of Vossenack while shying at enemy shellfire.

Both General Cota and General Davis nevertheless intended on 7 November to proceed with the attack on Schmidt by Task Force Davis. To ensure passage of the task force across the Kall, General Cota ordered another battalion of the 109th Infantry to go to the gorge and secure the bridge and the trail. An hour or so before dark on 7 November this battalion reported being in position, but the next morning General Cota was to learn that in reality the battalion had got lost in the forest and ended up a thousand yards southwest of Richelskaul in rear of the 110th Infantry. By daylight of 8 November, General Cota still had issued no movement orders for Task Force Davis. At the task force command post a belief gained credence that the orders might never come. For by 8 November events at Kommerscheidt already had dictated a more realistic appraisal of the 28th Division's capabilities. During the evening of 6 November, while the issues at Vossenack and in the Kall gorge remained in doubt, the commander of the enemy's 89th Division, General Bruns, had convened the leaders of his 1055th and 1056th Regiments and the attached 16th Panzer Regiment. The inertia at Kommerscheidt, General Bruns said, must end. At dawn on 7 November the 89th Division was to strike in full force.33 As daylight came, a cold winter rain turned foxholes and shellholes into miniature wells and lowered a gloomy backdrop for the climax of fighting at Kommerscheidt. A solid hour of the most intense artillery and mortar fire left the gutted buildings in flames and the fatigued remnants of Colonel Flood's and Major Hazlett's battalions of the 112th Infantry in a stupor. Through the rain from the direction of Schmidt rolled at least fifteen German tanks. With them came a force of infantry variously estimated at from one to two battalions. In the pitched fight that followed, American tank destroyers knocked out five German tanks, while an infantry commander, Capt. Clifford T. Hackard, accounted for another with a bazooka.34 Still the Germans came on. They knocked out three of the tank destroyers and two of the American tanks. By noon German tanks were cruising among the foxholes on the eastern edge of the village. Enemy infantrymen were shooting up buildings and systematically reducing each position. The Americans began to give. Individually and in small groups, the men [368] broke to race across the open field to the north in search of refuge in the reserve position along the Kall woods line. Before the 112th Infantry commander, Colonel Peterson, could counterattack with a portion of his reserve from the woods line, a message arrived by radio directing him to report immediately to the division command post. Colonel Peterson did not question the message for two reasons: (1) he believed the situation at Kommerscheidt had been misrepresented to General Cota, and (2) he had heard a rumor that a colonel recently assigned to the division was to replace him as commander of the 112th Infantry. Designating Colonel Ripple to command the force east of the Kall, Colonel Peterson started the hazardous trip westward across the Kall gorge. Wounded twice by German shellfire, Colonel Peterson was semi-coherent when engineers digging along the firebreak west of the Kall came upon him in late afternoon. When medics carried him to the division command post, General Cota could not understand why the regimental commander had returned. Not until several days later did General Cota establish the fact that, by mistake, a message directing Colonel Peterson's return had been sent. In the meantime, at Kommerscheidt, Colonel Ripple found the situation in the village irretrievable. Reduced now to but two tank destroyers and three tanks, the armored vehicles began to fall back on the woods line. The last of the infantry took this as a signal to pull out. In withdrawing, two of the tanks threw their tracks and had to be abandoned. Only two destroyers and one tank remained. Aided immeasurably by steady artillery support, Colonel Ripple's battered force held through the afternoon at the woods line against renewed German attack. Yet few could hope to hold for long. Expecting capture, one man hammered out the H that indicated religion on his identification tags. Bearing the dolorous tidings that the Germans had ejected his forces from Kommerscheidt, General Cota talked by telephone during the afternoon of 7 November with General Gerow, the V corps commander. Cota recommended withdrawal of all troops from beyond the Kall. Concurring, General Gerow a short while later telephoned the tacit approval of the First Army commander, General Hodges. The army commander had kept in close touch with the 28th Division's situation and was "extremely disappointed" over the division's showing.35 On 8 November during a conference at the division command post attended not only by Hodges but by Generals Eisenhower, Bradley, and Gerow, General Hodges drew General Cota aside for a "short sharp conference." He particularly remarked on the fact that division headquarters appeared to have no precise knowledge of the location of its units and was doing nothing to obtain the information. Hodges later told General Gerow to examine the possibility of command changes within the division.36 Certain conditions went with General Hodges' approval of withdrawal from beyond the Kall. In effect, the conditions indicated that the army commander would settle for a right flank secured along the Kall River instead of the Roer. [369] WEASEL (M29 Cargo Carrier), similar to those used for evacuating wounded, pulls jeep out of the mud. General Gerow ordered that the 28th Division continue to hold the Vossenack ridge and that part of the Kall gorge west of the river, assist the attached 12th Infantry of the 4th Division to secure a more efficacious line of departure overlooking Huertgen, continue to drive south into the Monschau Corridor, and be prepared to send a regiment to work with the 5th Armored Division in a frontal drive against the Monschau Corridor. As events were to prove, these were prodigious conditions for a division which had taken a physical and moral beating. After locating the battalion of the 109th Infantry that had become lost en route to the Kall gorge, General Davis on 8 November directed the battalion to continue to the Kall. With the battalion went a new commander for the 112th Infantry, Col. Gustin M. Nelson, who was to join what was left of the regiment beyond the river and supervise withdrawal.37 Nearing the Kall bridge, the battalion of the 109th Infantry dug in along the [370] firebreak paralleling the Kall trail. Why a position was not chosen which would include the medical aid station in the dugout alongside the trail went unexplained.

Assisted by a volunteer patrol of four men, Colonel Nelson continued across the river where in late afternoon he reached his new, drastically depleted command. Preparations for withdrawal already were in progress. Soon after nightfall, while supporting artillery fired upon Kommerscheidt to conceal noise of withdrawal, the men were to move in two columns westward to the river. In hope of consideration from the Germans, a column of wounded and volunteer litter bearers was to march openly down the Kall trail. The column of effectives was to proceed cross country along the route Colonel Nelson and his patrol had taken. The night was utterly black. Moving down the eastern portion of the Kall trail, the column of wounded at first encountered no Germans; but enemy shelling split the column, brought fresh wounds to some, and made patients out of some of the litter bearers. At the bridge the men found four German soldiers on guard. A medic talked them into letting the column pass. With the effectives, Colonel Nelson found the cross country route through the forest virtually impassable in the darkness. Like blind cattle the men thrashed through the underbrush. Any hope of maintaining formation was dispelled quickly by the blackness of the night and by German shelling. All through the night and into the next day, frightened, fatigued men made their way across the icy Kall in small irregular groups, or alone. More than 2,200 men had at one time or another crossed to the east bank of the Kall. A few already had returned as stragglers or on litters; little more than 300 came back in the formal withdrawal. In the confusion of withdrawal, the litter bearers carried the wounded no farther than a temporary refuge at the log walled aid station alongside the western portion of the Kall trail. Situated in a kind of no man's land between the Germans and the battalion of the 109th Infantry along the firebreak, the medics for several days had been able to evacuate only ambulatory patients. Their limited facilities already choked, the medics had to leave the new patients outside in the cold and rain. After the Germans had turned back three attempts by weasels to reach the aid station, the medics decided early on 9 November to attempt their own evacuation. Along the Kall trail they found two abandoned trucks and a weasel. Though they loaded these with wounded, they found as they reached the western woods line that only the weasel could pass several disabled vehicles which partially blocked the trail. With instructions to send ambulances for the rest, the driver of the weasel and his load of wounded proceeded to Vossenack. By the time the ambulances arrived, a German captain and a group of enemy enlisted men had appeared on the scene. They refused to allow evacuation of any but the seriously wounded and medics with bona fide Red Cross cards. The two American surgeons and two chaplains that were with the aid group also had to stay behind. For the next two days, these officers and the remaining wounded stayed in the aid station, virtual prisoners. Not until late on the second day, 11 November, when a German medical officer at the bottom of the gorge requested [371] a local truce to collect German dead, did the American surgeons find an opportunity to bypass the enemy officer at the western woods line and evacuate their remaining patients.