2

LT. GEN. MARK W. CLARK

Commanding General, Fifth Army, United States Army

3

4

Introduction

BEFORE DAWN ON THE MORNING OF 13 OCTOBER 1943, American and British assault troops of the Fifth Army waded the rain-swollen Volturno River in the face of withering fire from German riflemen and machine gunners dug in along the northern bank. Water-soaked and chilled to the bone, our troops fought their way through enemy machine-gun pits and fox holes to establish a firm bridgehead. This crossing of the Volturno opened the second phase of the Allied campaign in Italy. Five weeks earlier the Fifth Army had landed on the hostile beaches of the Gulf of Salerno. Now it was attacking a well-defended river line.

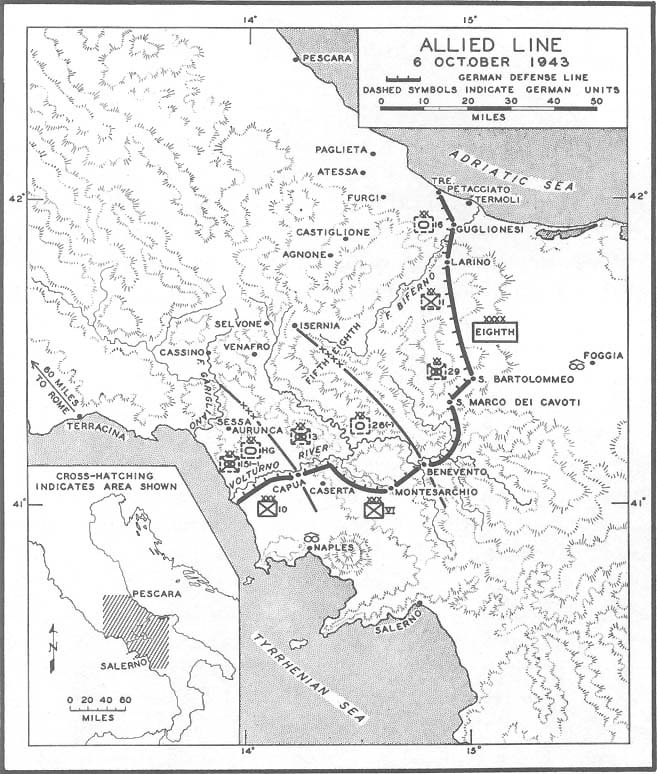

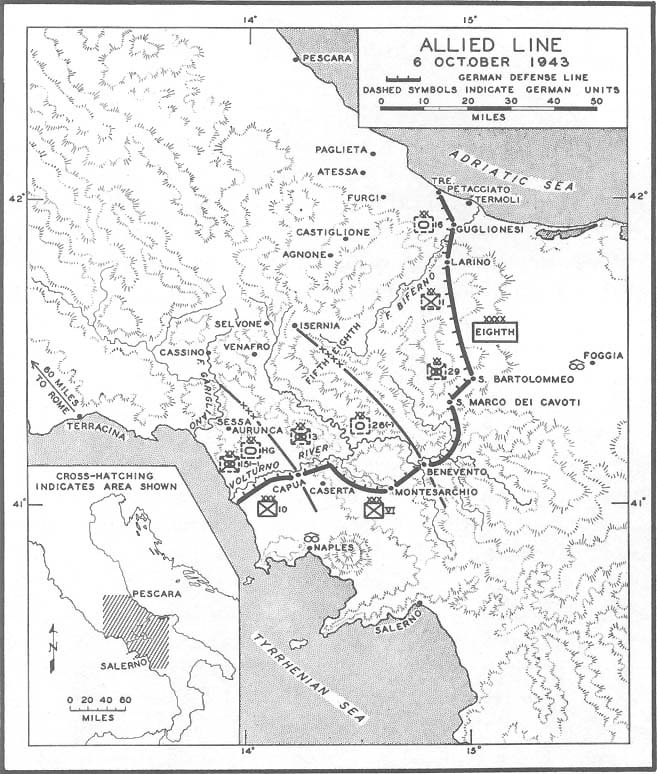

Along the Volturno the Germans had entrenched themselves in the first good defensive position north of Naples (Map No. 2, page 2). At Salerno they had fought for each foot of sand and counterattacked repeatedly, but after our beachhead was secure, they had carried out an orderly withdrawal. Under pressure from the Fifth Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark, their rearguards had relinquished the great port of Naples with its surrounding airfields, providing us with the base necessary for large-scale operations west of the rugged Apennine mountain range, backbone of the Italian peninsula. East of the Apennines the British Eighth Army, under General (now Field Marshal) Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, had reached the mouth of the Biferno River during the first week of October. The Eighth and Fifth Armies now held a line across the

1

peninsula running south from Torre Petacciato on the Adriatic Sea for some sixty-five miles, then west to a point on the Tyrrhenian Sea just south of the Volturno. Along this line of rivers and mountains the Germans clearly intended to make a stubborn stand, hoping to delay, perhaps to stop, our northward advance.

Fifth Army Prepares for the

Second Phase of the Italian Campaign

On 15 September, 15th Army Group, under General Sir Harold R. L. G. Alexander, instructed Fifth Army to cross the Volturno

2

LT. GEN. MARK W. CLARK

Commanding General, Fifth Army, United States Army

3

4

River and drive the enemy some thirty miles northward into the mountains which extend from Sessa Aurunca, near the Tyrrhenian coast, through Venafro to Isernia, the point of junction with the Eighth Army (Map No. 3, opposite page, and Map No. 30, inside back cover). For the task of carrying out army group instructions General Clark had U. S. VI Corps, commanded by Mal. Gen. John P. Lucas, and the British 10 Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Sir Richard L. McCreery. VI Corps was composed of three of the finest battle-tested divisions in the U. S. Army: the 3d Division, under Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr.; the 34th Division, under Maj. Gen. Charles W. Ryder; and the 45th Division, under Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton. The British 10 Corps was also composed of three seasoned divisions: the 46 Division, under Maj. Gen. John L. I. Hawkesworth; the 56 Division, under Maj. Gen. Gerald W. R. Templer; and the 7 Armoured Division, under Maj. Gen. George W. E. I. Erskine. Together with their supporting units the two corps constituted a force of over 100,000 fighting men. (See chart, page 118.)

To oppose the Fifth Army, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commander of the German Tenth Army, had the 3d and 15th Panzer Grenadier Divisions, the Hermann Goering Division, and elements of the 26th Panzer Division. Kesselring's force was smaller than Fifth Army, but it was fighting a delaying action in terrain and weather which gave every advantage to the defense.

The western part of the area from which Fifth Army had to drive the enemy in order to reach the line of mountains designated as its objective is a broad stretch of level farm land fifteen to twenty miles wide extending northwest along the coast approximately thirty miles from Naples to the Mount Massico ridge line. It is a fertile region of vineyards, olive groves, and carefully tilled fields, dotted with towns. This coastal plain was the zone of advance assigned by General Clark to 10 Corps. The Volturno River, flowing west across it, provided the enemy with a strong defensive position. General Clark ordered 10 Corps to drive to the Volturno, force a crossing of the river, and continue through the plain to seize the Mount Massico ridge.

To VI Corps was assigned the area of mountains and valleys stretching some thirty-five miles east from the coastal plain to include the eastern slopes of the massive Matese range, watershed of the peninsula. This mountain country varies from low hills covered with olive

5

orchards and terraced fields to barren rocky peaks about two thousand meters high. Villages of tightly crowded gray stone houses cling to the steep slopes, and crumbling ruins of ancient castles here and there look down on the green valleys below. The rugged mountains are a formidable obstacle to the movement of troops, and the Volturno and Calore rivers reinforce the barrier. The Volturno, rising in the high mountains north of Venafro, follows an erratic course southeast to Amorosi, where it is joined by the Calore. Then, turning west, it cuts through a narrow gap in the mountains at Triflisco and flows out into the coastal plain. The Calore rises in the mountains southeast of Benevento and flows generally westward to its junction with the Volturno. The lower reaches of the Volturno and Calore form a continuous obstacle, almost sixty miles long, lying directly in the path of any advance on Rome from the south. If the Fifth Army should breach the river defenses, the enemy would have to fall back to the range of mountains behind Sessa Aurunca, Venafro, and Isernia. There the Germans were already building even stronger defenses later known as their "Winter Line." Time was vital. Delay favored the enemy. He had more time to improve his defenses, and the continual autumn rain, swelling the river and turning the valleys to mud, made his defenses more difficult to approach.

A preliminary objective of VI Corps was Benevento, which it was ordered to capture with one division. This division was then to drive north and west twenty-two miles down the Calore Valley to the Volturno, turn northwest up the valley of the Volturno, and advance some thirty miles to the mountains behind Venafro. The two remaining divisions of the corps were to cross the Volturno on a 15-mile front between the junction of the rivers and the Triflisco Gap. Then they were to push northwest through the hill mass lying between the upper Volturno and the coastal plain to the army's immediate objective, the mountain complex just north of Sessa Aurunca. General Clark's orders to the two corps under his command established the over-all plan for the second phase of the Italian campaign.

Getting Into Position

Before detailed plans for an attack on the river line could be worked out it was first necessary to capture Benevento, the key road and ran center on Fifth Army's right flank, and to bring all units up to the

6

7

Volturno (Map No. 4, page 7). The enemy made no serious effort to hold the ground south of the river. His tactics were to delay the advance of our troops with small mobile units while his engineers mined the roads and blew every culvert and bridge. Each day that he gained gave him additional time to strengthen his position north of the Volturno River.

The task of capturing Benevento and securing Fifth Army's right flank was shared by the 34th Division (132d, 135th, and 168th Regimental Combat Teams) and the 45th Division (157th, 179th, and 180th Regimental Combat Teams). On 2 October, General Lucas ordered the 34th Division to capture the city. At 1200 a platoon of the 45th Reconnaissance Troop carrying out routine patrol duties entered Benevento. The debris-littered streets, filled with the rubble from our bombing and German demolition, were silent. The enemy had withdrawn across the Calore River. It was not necessary to capture Benevento; the city had only to be occupied. Early the next morning the 133d Infantry, after completing a difficult night march through a drizzling rain, entered the city and established a bridgehead across the river. That same day the 34th Division was placed in corps reserve and the task of expanding the bridgehead passed to the 45th Division. While the engineers set to work clearing the roads through Benevento and repairing the bridges destroyed by the Germans before they withdrew, the infantry drove the enemy back through the rolling hill country lying to the north. By 9 October, the 45th Division had completed the work of securing the army's right flank and was ready to drive west down the Calore Valley to the Volturno.

General Lucas assigned the 3d Division (7th, 15th, and 30th Regimental Combat Teams) the task of pushing northwest to reach the Volturno on a front extending from the junction of the Volturno and Calore rivers to the boundary with 10 Corps, just to the west of the Triflisco Gap. On 2 October, when the order was received, the division was in the vicinity of Avellino, some thirty miles southeast of the river and deep in the mountains. The troops took immediately to the road.

The 15th Infantry on the left flank drove west down Highway 7 Bis to the coastal plain, Then skirting the edge of the mountains, it entered the light gray limestone hills lying north and east of Caserta.

8

ROYAL PALACE AT CASERTA

On the west side of the town, troops of the 1st Battalion passed by the royal palace of Caserta built by King Charles III of Naples in the eighteenth century. A huge structure containing nearly twelve hundred rooms, the palace is large enough to have housed the whole 3d Division, but the troops had no time to enjoy the luxuries of a royal estate. Pushing on across the formal gardens, which extend back for a mile and a half to the hills, the 1st Battalion, on 6 October, occupied Mount Tifata, a sharp-peaked mountain overlooking the Triflisco Gap where the Volturno enters the coastal plain. The next day the 2d Battalion, fighting through the hills east of Caserta, reached the rocky crest of Mount Castellone. From their excellent observation posts on Mount Tifata and Mount Castellone 15th Infantry observers could look down on the brush-covered banks and turbulent waters of the river across which they would soon fight their way.

On the division's right flank the 30th Infantry was engaged in clearing the V-shaped valley lying between the hills east of Caserta and the junction of the rivers. The broad belt of farm land on the south side of the Volturno offered no covered routes of approach to the river; on the north side, however, brush-clad hills come down almost to the

9

river bank, giving the. enemy concealment as well as excellent observation over the whole valley. After two days of hard fighting, the 30th Infantry on 8 October completed the work of driving the last enemy rearguard units across the river.

While the 45th Division was expanding its bridgehead across the Calore River at Benevento and the 3d Division was working its way through the mountains to the Volturno, 10 Corps had been driving north across the coastal plain. By 7 October it had reached the Volturno and had cleared the whole area from the mountains to the sea. Before withdrawing across the river, the enemy destroyed what was left of the bridges. The important bridges had already been knocked out in September by our air force, blocking the enemy supply lines to the south. With all bridges out, the 200- to 300-foot-wide river, swollen by the almost daily rains of the first week of October, presented a formidable obstacle. A pause in the operations was necessary so that the Fifth Army could bring up bridging equipment and prepare for a coordinated attack.

Orders Are Issued for the Attack on the Volturno

With 10 Corps and the 3d Division holding the ground on the south bank of the river, General Clark, on 7 October, issued his orders for the attack on the Volturno (Map No. 4, page 7). VI Corps was instructed to force a crossing of the river on the night of 9/10 October in the vicinity of the Triflisco Gap and drive along the ridge line running northwest from Triflisco in the direction of Teano. 10 Corps was to attack the next night. In working out the details of VI Corps' part in the attack General Lucas was faced with the fact that the 3d Division was holding a front of almost fifteen miles extending from the Triflisco Gap to the junction of the Volturno and Calore rivers. If the 3d Division was to launch an effective attack at Triflisco, concentration of its forces was necessary. Accordingly, General Lucas ordered the 34th Division, which was in corps reserve, to take over the sector held by the 30th Infantry and to make immediate preparations to join the 3d Division in a coordinated assault on the enemy defenses across the river. The 45th Division also had an important role to play. If it could drive the enemy down the Calore Valley as far as the upper Volturno Valley, it would be in position to threaten

10

the flank of the enemy opposing the 34th Division. By 8 October the over-all plan of attack was set. There remained only the question of how quickly the 34th Division could move into line.

The 34th Division Moves Into Line

After the 133d Infantry had taken Benevento on 3 October, the 34th Division had been ordered to assemble in the vicinity of Montesarchio, eighteen miles to the cast of Caserta (Map No. 4, page 7) Although the march to this new area involved no fighting with the enemy, combating the weather and the rough mountain roads was a battle in itself. Beginning with a terrific thunderstorm which struck the area on the evening of 28 September, rain followed day after day. The curse of rain and mud dogged the footsteps of our troops all the way to the Volturno. When VI Corps orders for the relief of the 30th Infantry reached General Ryder, the 34th Division was still in the process of assembling its troops around Montesarchio.

A BRIDGE NEAR MONTESARCHIO was wrecked by the withdrawing enemy. Demolitions have reduced the stonework to rubble; the rails remain hanging in mid-air. Orders to the Goering Engineers were comprehensive, "Destroy: bridges, stations, water, gas and electricity works, factories, mills. Mine: roads, houses, and entrances to villages."

11

MONTESARCHIO, ON HIGHWAY 7, has a narrow plain intensely cultivated.

The trees support vines above

the stubble of a grain field in this view near a 34th Division bivouac.

Mount Taburno, with olive trees terraced

on its lower slopes, rises in the background.

At 1510 on 8 October the 30th Infantry, in the valley east of Caserta, received the news that it was to be relieved. Any shifting of troops until after dark was impossible as German artillery fired on anything that stirred in the valley. Blown bridges and muddy roads further complicated the task of getting men and equipment out of the area. At 0720 the next morning the 1st Battalion reported that, with the exception of about eight jeeps, all its transportation, including signal equipment, was bogged down. The battalion had suffered heavy casualties from enemy artillery fire and the wounded had to be moved out on stretchers. The tasks of clearing out the Germans, patrolling the river banks for crossing points, and trying to keep dry and warm in the rainy weather were impossible. When the regiment was relieved, the first two tasks were nearly completed, but not the third. The men had not yet received their barracks bags which, owing to lack of shipping space, had been left in Sicily. Still dressed for summer weather, they shivered through the cold, rainy fall nights. Col. (now Brig. Gen.) Arthur H. Rogers, the commander, reported on

12

the afternoon of 8 October that four of his officers had just been evacuated "mainly due to overexposure." Fortunately, the relief of the 30th Infantry gave the men an opportunity to dry out and to eat a hot meal. Instructions were issued that in the new bivouac area west of Caserta each battalion was to occupy one public building in which the men could dry their clothes.

The task of relieving the 30th Infantry was assigned by General Ryder to the 135th Infantry. All the difficulties of rain, mud, and poor roads which slowed the work of drawing the 30th Infantry out of line delayed the advance of the 135th Infantry. For the 34th Division to launch an effective attack across the river, more time was needed than original plans allowed. Since 10 Corps also required further time to get set, General Clark postponed the crossing to the night of 12/13 October. This shift gave the 34th Division an additional three days in which to complete the assembling of troops, reconnoiter the river line, and work out the details of its plan of attack.

Preparations by 3d Division

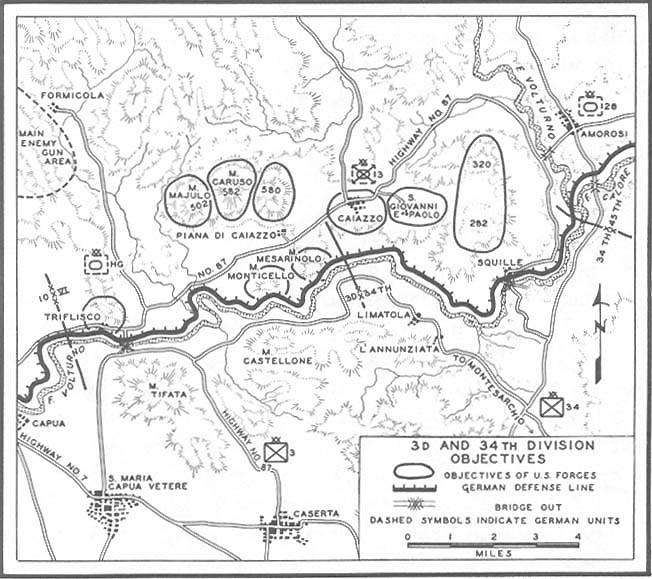

After the orders had gone through for the relief of the 30th Infantry on the afternoon of 8 October, General Truscott called a meeting of his regimental commanders and outlined his plan of attack (Map No. 5, page 14). The plan was built on a careful appreciation not only of the obstacle presented by the river but of the terrain over which his troops would have to fight on the north bank in order to secure a necessary bridgehead.

The critical terrain feature in the 3d Division zone was the ridge line running northwest from Triflisco. The ridge is actually an extension of Mount Tifata broken by the narrow gap formed by the Volturno River in forcing its way through the mountains to the coastal plain. The gap is so narrow that troops of the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry, dug in on the northern slopes of Mount Tifata, were exchanging small-arms fire with enemy troops hidden in the stone quarries and olive orchards on the north side of the gap. As long as the enemy held the ridge line, he would be in position to dominate the valley lying to the east and to command the best site for a bridge in the 3d Division zone. Highway 87, running northwest from Caserta along the east and north sides of Mount Tifata, crosses the

13

river within the Triflisco Gap and then cuts east across the valley toward Caiazzo. The natural site for the engineers to build a bridge for heavy vehicles was somewhere within the gap where the road parallels the river on both sides.

Of almost equal importance with the Triflisco ridge was the hill mass to the east, Mount Caruso. It overlooks the Volturno Valley stretching two miles south to the river and dominates the narrow valley leading northwest along the 3d Division's axis of advance. Just north of the river on the division's right flank are two smaller hills, Mount Monticello and Mount Mesarinolo. Rising from the level valley like solitary outposts, they serve to guard the approach to the Mount Caruso hill mass, Air photographs indicated that these two hills, as well as the nose of the ridge at Triflisco, were strongly defended by the enemy. Almost surrounded by the hills, the fertile valley of the lower Volturno, through which the river follows its winding course, presents a peaceful scene of cultivated fields and pink or blue farmhouses. It is a beautiful valley, but for the soldier trying to work

14

THE VOLTURNO VALLEY stretches out below the forward slopes of Mount

Tifata. In the foreground Highway 87 runs parallel to the river as far

as Triflisco Gap, then doubles back along the north bank. In the central

background

is the Mount Caruso hill mass.

his way forward under the fire of enemy machine guns and mortars there was only an occasional stone wall, sunken road, or stream bed to offer protection. A rapid advance into the hills overlooking the valley was therefore essential to the success of the 3d Division attack.

Aware that the enemy would be well prepared for any attack made across the Triflisco Gap, General Truscott planned to fake an attack on the left flank while making his main effort across the valley in the center. To effect this deception, the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry, and the heavy weapons companies of the 30th Infantry were to concentrate all their available fire power on the enemy defenses across the gap. The demonstration was to start at midnight, two hours before the main assault, and continue for the remainder of the night. If the enemy showed any sign of withdrawing, the 2d Battalion, 30th Infantry, was to cross the river, but, until such time as the enemy could

15

be cleared from the ridge line, it was to be kept blanketed with smoke. While the enemy was being diverted by the demonstration on the left, the big push was to be made in the center by the 7th Infantry, under the command of Col. (now Brig. Gen.) Harry B. Sherman, crossing the river at 0200 and attacking through the valley with Mount Majulo as its first objective. Company A of the 751st Tank Battalion and Company C of the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion were to cross the river at daylight to support the 7th Infantry attack. Sufficient materials were available to waterproof the tanks and tank destroyers of these two companies, and it was expected that they would be able to ford the river. On the division right flank, the 15th Infantry (less the 1st Battalion), under the temporary command of Brig. Gen. (now Maj. Gen.) William W. Eagles, was to attack north from Mount Castellone. Its first objectives were the German strongpoints on Mount Monticello and Mount Mesarinolo. Once these hills were taken, the regiment was to capture the high ground above the village of Piana di Caiazzo, secure the division right flank, and move west behind the 7th Infantry.

The key to the strategy of the 3d Division attack was surprise. Only the 15th Infantry had units along the front chosen for the division attack. The 7th Infantry had been kept in its concealed bivouac area east of Caserta, and the 30th Infantry had been in contact with the enemy only in the area now assigned to the 34th Division. The strength of the artillery, which was to fire a massed concentration for an hour before the infantry jumped off, was also unknown to the enemy. Instructions were issued on 9 October that the artillery was to fire each morning for an hour but that not more than half of the guns were to be used. Every effort was being made to keep the enemy from knowing where the blow would fall and the amount of punch behind the blow. Once the attack was started, however, there was to be no pause. As General Truscott expressed it to his officers, "This is undoubtedly going to be our first real battle-we must have the men imbued with the idea that they have to get to their objective and they won't stop."

The decision to delay the attack to the night of 12/13 October gave the regiments time to make a detailed study of the river. Although air photographs proved an invaluable aid in locating enemy defenses and in selecting possible sites for bridges, the only sure method of

16

finding the depth of the river, locating good crossing points, and feeling out the enemy defenses along the river banks was to send out patrols. With the enemy guarding the river along the north bank and often sending his own patrols across the river into our lines, almost every one of our patrols encountered enemy fire at some point, and few came back intact.

A patrol from the 2d Battalion, 7th Infantry, sent out on the night of 11/12 October, may be described as typical of dozens of others which probed the river for crossing points. After reaching the river a short distance upstream from the hairpin-shaped loop in the center of the division zone, the men waded out into the dark, swirling

17

stream. Although the water was not over chest deep, the current was very swift, and the men found it impossible to get rope across. The bank on the south side was sloping. The bank on the north side was ten feet high, straight up, and lined with bushes and trees. Moving downstream to the bend in the river just below the hairpin loop, the patrol again waded out into the river. Before the men were across, enemy troops on the far bank opened fire. One man fell. The patrol succeeded in getting back to the south bank, and a fire fight ensued between our machine guns and enemy machine guns and mortars located on both sides of the hairpin loop. Nevertheless, the bend in the river appeared to be a good place to cross since vehicle tracks leading into the water suggested that the enemy had once operated a ferry or a raft there. Although two possible crossing points had been tested, the patrol moved farther downstream and made yet a third effort to cross. The patrol report states simply that "one man was across when fired on point-blank. He did not return but crossing by wading is possible." Seven members of the patrol were casualties, including three missing in action. The men who patrolled are the real heroes of the Volturno crossings: men who waded alone across a flood-swollen river 200 feet wide, never knowing when they might sink over their heads in the icy water or when the crack of an enemy rifle would spell sudden death; men who had to lie helpless and shivering on a muddy bank and watch a comrade be shot as he struggled with the current and who could then themselves move downstream and wade out into the river. It was grim work, but for every man who lost his life searching for crossing points and probing the enemy defenses the lives of hundreds of other men were saved when whole battalions had to fight their way across the river.

Back at battalion, regimental, and 3d Division Headquarters the patrol reports were fitted together with the information gained from other sources, such as aerial photographs, the excellent observation posts established on the high ground south of the river, enemy prisoners, Italian civilians, and our own men who escaped from German prison camps and filtered through the enemy lines. The essence of these reports may be summarized briefly: open fields giving no covered approaches to the river, high and steep mud banks often covered with brush and small trees, water waist-to-chest deep, current swift, Ger-

18

man patrols equipped with rifles and machine pistols guarding the north bank, and German machine-gun emplacements all along t he river. There was one bright spot in the picture: despite the increased depth of the water caused by the continual rains, it was still possible for infantry to ford the river at points within each regimental sector.

In the bivouac areas the infantry was assembling equipment needed for the assault battalions. The most important item proved to be rope for guide lines, but there were a number of other items, some standard, some improvised. Nearby a thousand Italian kapok life-preserver jackets were found in a local warehouse, and rubber life rafts were borrowed from the Navy. The engineers provided assault boats and rubber pneumatic floats. Some of the units constructed improvised rafts from the wooden bows and canvas covers of 3/4-ton weapon carriers to be used to ferry machine guns, mortars, and ammunition across the river. While this equipment was being assembled, the engineers were selecting sites for the bridges which were to carry vehicles and supplies across behind the attacking infantry.

The 34th Division Prepares To Attack

By 10 October the 34th Division had completed the relief of all 3d Division troops in its sector of the front and was working out the details of its plan of attack (Map No. 5, page 14). Ahead of the division lay a jumbled mass of low hills resembling a clenched fist thrust out toward the high mountains to the southeast. At the foot of this hill mass the Volturno River flows in an irregular half circle like a moat protecting a medieval fortress. With the 34th Division troops in the valley and the enemy holding the hills behind the river, all the advantages of observation lay with the enemy. He would have to be driven back from the forward line of hills before it would be possible to put in bridges or even to make use of the roads leading to the bridge sites.

General Ryder's orders for the attack, issued on 11 October, divided the division front of approximately eight miles between the 168th Infantry, which was to make the main effort on the left toward Caiazzo, and the 135th Infantry, which was to attack on the right. The 133d Infantry was to be held in division reserve, with one battalion prepared to move whenever directed. Since the high ground directly

19

north of the river prevented any immediate use of tanks, the 756th Tank Battalion was ordered to remain in its assembly area.

The plan of attack of Col. (now Brig. Gen.) Frederic B. Butler, commanding officer of the 168th Infantry, called for a crossing by the 1st and 2d Battalions with the first objectives of capturing the high ground around San Giovanni. From there they were to move northwest through Caiazzo to contact the 3d Division. Crossing sites were selected on the basis of the experience gained from two nights of patrol reconnaissance. On the night of 10/11 October a 1st Battalion patrol consisting of two officers and seven enlisted men probed the area west of Limatola. The patrol followed a ditch between two rows of trees to within fifteen feet of the river bank. Three enlisted men, roped together, went on to wade the river. As they crossed, four enemy machine guns started firing bursts of tracer ammunition. The fire appeared to be high as though coming from the second floor of a building. They saw two lights in a nearby building and heard German voices. As the patrol left the scene, snipers inland and downstream fired at the deployed men. The patrol reported that this was a good place to ford the river, but that it was well guarded. The next night a patrol, accompanied by engineer officers, reached the river six hundred yards downstream from the ford. The engineers located a place where assault boats could be used to ferry the infantry across the river, and it was decided that the 1st Battalion, less one company, would cross at this point, the remaining company to cross at the ford. The 2d Battalion located a good ford north of L'Annunziata where the engineers planned to build a bridge. During the day Of 12 October men of all companies of the 1st and 2d Battalions were given dry-land practice with assault boats.

Foot troops of the 135th Infantry on the right flank of the division also found points to ford the river. In most places the steep muddy banks and the sandy bottoms made use of vehicles impractical though at one spot near an old dam it appeared that waterproofed vehicles could cross. Col. Robert W. Ward, commanding officer of the regiment, ordered the 1st Battalion and E Company to lead the assault to their objective, the high ground behind the village of Squille. When this objective was taken, the 2d Battalion was to pass through and continue the advance. To assist the men in keeping together in the darkness, all troops were directed to wear a strip of white tape down the center of their packs.

20

21

Drive to the West by the 45th Division

After the 45th Division had won control of the area north of Benevento on 9 October, General Middleton ordered the 180th Infantry to leave one reinforced battalion to guard the right flank while the remainder of the division drove west down the Calore Valley (Map No. 6, page 21). There was no "zero hour" for the 45th Division. It was rather a continuing race against time. The nearer the division could come to reaching the Volturno before the 3d and 34th Divisions attacked, the more effective would be the combined VI Corps assault.

The valley down which the 45th Division had to advance some fifteen miles to reach the Volturno is a corridor four to five miles wide, bounded on the north by the towering peaks of the Matese range and on the south by the Mount Taburno hill mass. Unlike the Volturno Valley, which is almost as level as the coastal plain, the Calore Valley is a succession of rough hills and open fields. The enemy took advantage of the numerous ravines which cut through the hills to conceal machine-gun and mortar positions, and enemy engineers blocked the roads by destroying every bridge. Even where the bridges were small, it took hours of work to replace them or to construct bypasses through fields turned into sticky mud by the continual rains.

On 9 October the 157th Infantry, which had borne the brunt of the fighting to open the way for the swing to the west, was placed in division reserve and the 179th Infantry passed through it to clear the northern half of the valley. By 12 October it was nearing the last line of hills barring the approach to the upper Volturno Valley. The 1st Battalion reached the lower slopes of the Matese range and proceeded down the valley of the Titerno Creek, a small stream flowing west along the base of the mountains. The battalion's task was to break through the narrow gorge between Mount Monaco, the most southern peak of the lofty Matese range, and Mount Acero, a wooded round-topped mountain only four miles from the upper Volturno. The 3d Battalion marched cross-country to attack Mount Acero from the east and from the south.

The 1st and 2d Battalions, 180th Infantry, following the road which runs along the north bank of the Calore, also made good progress. On 12 October the 2d Battalion reached the line of low hills lying south of Mount Acero. For a moment it appeared that the drive to the Volturno would beat the schedule, but it was only for a moment.

22

SOUTH OF AMOROSI and east of Castel Campagnano the Calore and Volturno

rivers join in this plain. The

45th Division, on the east of the Volturno, encountered the Germans

in dug-in positions and supported by tanks protecting river crossings already

mined.

Shortly after 1400 the enemy poured small-arms, machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire into the positions of the 2d Battalion and then threw approximately two hundred men against the battalion's right flank. Capt. Jean R. Reed, 2d Battalion commander, was wounded. He was the third battalion commander lost by the regiment in twelve days of almost continual fighting. The attack was beaten off before dark with the able assistance of the artillery and the 645th Tank Destroyer Battalion. The 27th Field Artillery Battalion alone fired three thousand rounds during the engagement, and reserve ammuni-

23

24

tion of the 158th and 160th Field Artillery Battalions had to be brought up to relieve the shortage. No ground had been lost, but the power behind this German attack indicated that the 45th Division would not reach the Volturno without a fight.

Fifth Army Is Poised To Strike

When the decision was made to postpone the date of the attack to the night of 12/13 October, it became possible to launch a coordinated attack by 10 Corps and VI Corps striking simultaneously along the whole extent of the forty-mile-long Volturno-Calore line (Map No. 7, opposite page). 10 Corps had originally planned to concentrate its main attack at Capua near the 3d Division left flank. As reports came in that this was a difficult place to cross the river, it was decided that the attack should be made along a wide front with the main effort on the left, where tanks loaded on LCT's (Landing Craft, Tanks) were to make an amphibious landing north of the river mouth. The assault was to be made with one brigade (equivalent to U. S. regiment) of the 56 Division attacking on the corps' right flank at Capua, one brigade of the 7 Armoured Division in the center at Grazzanise, and two brigades of the 46 Division on the left at Cancello. The amphibious tank landing was to assist the 46 Division. Thus, 10 Corps, as well as VI Corps, was attacking with a three-division front. Together they made Fifth Army a powerful striking force.

On the north side of the Volturno, Kesselring's troops were waiting for the impending battle. During the days when Fifth Army was moving up to the river and completing preparations for the attack, the enemy had been hard at work laying mines, digging gun pits, and organizing a system of machine-gun emplacements to cover the river banks with interlocking bands of fire. Enemy artillery was zeroed in on the most likely sites for the construction of bridges, and mobile units, held back from the river line, were prepared to move to any threatened sector. Near the coast, in 10 Corps zone, concrete pillboxes and road blocks, built by the Italians as part of a system of fixed coastal defenses, served to reinforce the more hastily constructed German field works. Finally, before our men could reach the enemy defenses, they must first battle their way across the swift waters of the

25

Volturno and up the steep mud bank on the far side. Their only advantage lay in their numerical superiority; and their hope of quick success lay in surprise. The enemy did not know at what time or at what point the blow would come.

On the evening of 12 October as darkness settled over the Volturno, a full moon rose, lighting up the sharp peak of Mount Tifata and spreading an eerie glow over the open fields in the valley. For once there was to be no rain. The enemy had no reason to suspect that a major battle was impending. Our customary night patrols worked their way down to the river, drawing an occasional burst of machinegun fire from the enemy bank or causing a nervous German outpost to shoot off a colored signal flare. This had been going on for days and signified nothing out of the ordinary to the enemy troops in their fox holes and gun emplacements. Back in our rear bivouac areas, it was a different story. Here was all the bustle and ordered confusion which accompany the movement of troops. Tank drivers warmed up their motors, engineers loaded rubber pontons onto trucks, artillerymen studied their fire plans, and long lines of infantrymen marched out to their forward assembly areas. The preparatory phase of the Volturno crossing was over; Fifth Army was ready to strike.

26

page created 17 September 2001