Conclusion

THE WINTER LINE campaign ended in mid-January with Allied gains on both

sides of the Apennines. To the east, the British Eighth Army had crossed

the Sangro and Moro rivers and made a thirteen-mile advance, principally

in the area near the Adriatic coast. On a thirty-five mile front, Fifth

Army had forced the enemy back into his Gustav Line and reached the edge

of the Liri Valley, main corridor for advance to Rome from the southeast.

In both zones, a stubborn and skillful enemy had limited the Allied success,

and his defense had never disintegrated; neither Fifth nor Eighth Army

had been given an opportunity to make the hoped-for breakthrough, either

by opening up the Liri Valley or by a northeast flanking maneuver past

Ortona toward Rome.

Nevertheless, in view of difficulties faced, Fifth Army's accomplishment

was notable. Measured in miles of advance the gain may not seem great for

two months of fighting. But this progress had been made against an enemy

who was defending with his main forces the strongest system of fortifications

yet encountered in Italy. The enemy had been defeated on ground of his

own choosing, whatever difficulties this ground presented. He would have

plenty of opportunity, in the rugged mountains of central Italy, to stand

and fight on other organized defensive systems, but the Allies had shown

their determination to assault such lines, and their ability to carry them

under the most adverse conditions of weather and terrain.

Winter, ideal defensive ground, and the enemy's hard fighting made the

Winter Line operations not only slow but costly. Combat units paid heavily

for local successes, which they could not exploit fully because reserves

were never sufficient to force a breakthrough.

113

Fifth Army battle losses from 15 November to 15 January were 15,930

men. Over half this numberó8,844ócame from American divisions and represented

a casualty rate of ten percent. Non-battle casualties were much higher,

numbering nearly fifty thousand for all the American elements of Fifth

Army.

Enemy strength had been even more severely taxed, the two thousand prisoners

taken in this campaign by Fifth Army representing only a small part of

German losses. Their local reserves had been used to the point where the

Germans could not mount a counteroffensive; moreover, their defense of

Rome and central Italy became

increasingly difficult, however strong the defensive lines. The value of the

Allied effort and the damage done to German military strength became clearer

in the course of 1944. In the larger background of the European theater, every

victory by the Allies in Italy, every increase in pressure on the Germans holding

the Italian front, made it less and less possible for Hitler's high command

to draw from Kesselring's twenty-two divisions for reinforcement of other fronts

against the mounting Allied threat. The enemy having decided to fight it out

in Italy, Allied armies were waging offensive warfare calculated to make him

pay a maximum price for his decision.

114-115

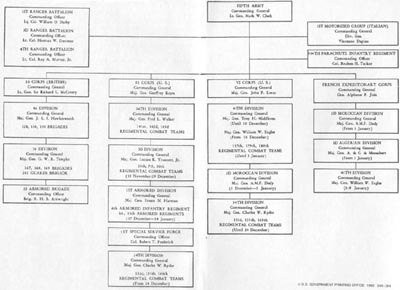

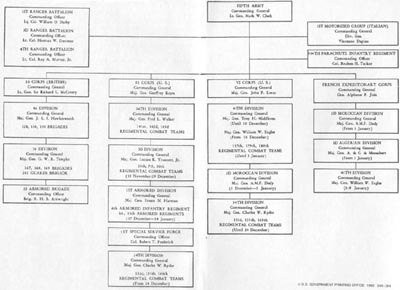

ORGANIZATION OF FIFTH ARMY

(15 November 1943 - 15 January 1944)

116-117

page created 20 July 2001

Return to the Table of

Contents

Return to CMH

Online