Soldier Returns Home to His Child

The Army of the Persian Gulf war presented a vastly different profile from the Army of the Vietnam War era. While the force of the 1960s consisted mainly of eighteen- and nineteen-year-old male draftees, volunteers, both male and female, comprised the Army of 1990.1 Moreover, the average soldiers were older, better educated, more highly trained, and had greater skills than soldiers of the immediate past, making them more difficult and expensive to replace. They were also far more likely to be married homeowners with dependent children than were soldiers of the Vietnam years.2

In 1973 the United States abolished the draft. Throughout the rest of the decade the Army had difficulty drawing enough volunteers, and the quality of recruits, as measured by the Armed Forces Qualification Test, was low. To obtain the necessary number and quality of volunteers in the 1980s, the Army pursued an aggressive publicity campaign, "Be All That You Can Be," and offered high school graduates substantial education subsidies, job training programs, and potential career advancement. Young people without the money for their education and those in dead-end service jobs found the incentives appealing. The Army College Fund offered potential recruits $17,000 towards college in exchange for two years of active service, $22,800 for three years, and $25,200 for four. That inducement attracted able people. The Army College Fund Plus, designed to attract recruits into hard-to-fill military specialties, offered

208

even greater educational benefits for commitments of two years of active duty, followed by two years in the Army Reserve.3

Both programs attracted high-quality recruits. Young men and women from every sector of society, except the poor and illiterate and the extremely wealthy, joined the Army. The recruits were ambitious, intelligent, dedicated, and upwardly mobile. In 1990 almost 98 percent of enlistees had high school diplomas, compared with a graduate rate of 75 percent among civilians of the same age. And although fewer than 3 percent of enlisted soldiers had attended college, two-thirds of those between eighteen and twenty-one years of age expected to do so, compared to 57 percent of their civilian counterparts.4 In any case, new recruits soon found themselves in the classroom, because all Army military occupational specialties required specific training.5

Soldier Returns Home to His Child

Supporters of the volunteer Army believed that the young blacks who joined the service represented an able and ambitious group. Edwin Dorn of the Brookings Institution reminded critics that "the kind of young men and women going into the military are not the kind that...would (otherwise) end up

209

pushing drugs...." The ones who did well in the Army did so because they had the drive necessary for success in whatever career they chose. Richard L. Fernandez, a Congressional Budget Office analyst, added that "a young man from a community with family incomes 20 percent below average [was] only slightly more likely to enlist than one from an area with incomes 20 percent above the average." Essentially, the Army that went to Southwest Asia was middle class and happened to be both black and white. The black soldiers did not think of themselves as cannon fodder or victims. Instead, they saw themselves as professionals doing the jobs for which they had trained.7

Some analysts claimed resumption of the draft would create an Army more representative of the total population. Department of Defense spokesmen reminded critics that the Army did not want a pool of soldiers that was representative of the general population. The Army did not accept men and women who scored in the lowest third of the Armed Forces Qualification Test. Such individuals would be both expensive to train and difficult to place in an organization with very few "unskilled" jobs.8

No one denied that many young people, both black and white, entered the military with career advancement rather than warfare in mind. But no evidence has been found that such soldiers were less ready to fulfill their military obligations when called to do so. On the contrary, the well-educated, highly trained Army of the Persian Gulf war consisted of soldiers who were more mature than their cohorts of the past and who had fewer disciplinary problems. Married homeowners with dependent children, they had greater stakes in society and took fewer risks. Research indicated that they made more thoughtful, analytical soldiers who performed exceptionally well under battlefield stress.9

Sociologist Charles Moskos of Northwestern University agreed. He believed that women provided the "margin of success" for the all-volunteer force. Without women with superior formal education and mental test scores, the Army would have had to rely on less qualified male volunteers. Women, he said, allowed the United States to maintain the quality of its armed forces without conscription.11

In 1991 minorities and women constituted 49.1 percent of the Regular Army. The enlisted force was 41.3 percent minorities, with minority

210

women making up 56.4 percent of enlisted females. Black women comprised 49 percent of enlisted females. Minorities made up 16.4 percent of the officer corps, with 25.6 percent of female officers from minority groups. Women accounted for over 11 percent of the Regular Army and 8 percent of the regulars deployed to the Persian Gulf. Women also accounted for 20.5 percent of Army reservists and 17 percent of the reserve soldiers in Saudi Arabia at the height of the conflict. All told, over 26,000 women from active and reserve components went to Southwest Asia. Women represented over 8.6 percent of the Army's deployed force.12

Although federal law mandated that the Navy and Air Force prohibit women from serving in direct combat roles, no such law bound the Army to do so. Instead, the Army used its combat exclusion policy to regulate itself to conform to the intent of the federal laws that affected the other services. Thus, the Army's combat exclusion policy limited women from direct combat. That policy defined direct combat as "engaging an enemy with individual or crew-served weapons while being exposed to direct enemy fire, a high probability of direct physical contact with the enemy's personnel, and a substantial risk of capture." According to the Army, "Direct combat takes place while closing with the enemy by fire, maneuver, or shock effect in order to destroy or capture, or while repelling assault by fire, close combat or counterattack."13

The Direct Combat Probability Coding System implemented the combat exclusion policy. The coding system evaluated every position in the Army based on its duties and the unit's mission, tactical doctrine, and position on the battlefield. The Army coded each position based on the probability of engaging in direct combat, with P1 representing the highest likelihood and P7 the lowest. Women were prohibited from P1 positions. An entire specialty could be closed to them if the number or grade distribution of positions coded P1 made advancement or development in that area impossible for women. At the time the Persian Gulf crisis occurred, 86 percent of all military occupational specialties in the Army were open to women.14

Army officials told the General Accounting Office in 1987 that battlefield location had the greatest impact on the rating of a position. The service generally rated jobs located forward of the brigade's rear boundary as P1, thus making them closed to women. However, women could move forward of the brigade's rear boundary temporarily to deliver supplies or fix equipment. Furthermore, no limit existed on how far forward a woman could travel during a temporary excursion.15 Throughout the Persian Gulf war women visited the forward-deployed units periodically but were not stationed there.

Prevented by policy from assignments to direct combat positions, women served in jobs generally classified as combat support and combat service support. Combat support assignments, which provided operational help to the combat units, included civil engineering, military police, transporting personnel and equipment via truck or helicopter,

211

communications, and intelligence support. Combat service support positions provided logistical, technical, and administrative services (such as personnel, postal, medical, and finance) to the combat arm. Female soldiers worked in high concentrations in these areas. Black women, for example, represented a majority of the force in the following career fields: supply and services (55 percent), petroleum and water (58 percent), administration (52 percent), and food services (54 percent).16

The concentration of minorities and women behind the front lines in these roles resulted in relatively low casualty rates among these groups. As of 11 April 1991 the casualty count was as follows: whites killed in action-74 (78 percent), blacks killed in action-12 (13 percent), white nonbattle deaths-80, black nonbattle deaths-23, whites wounded in action-247, blacks wounded in action-95, white nonbattle injuries- 167, and black nonbattle injuries-57. Eight women were killed, 5 in action and 3 in accidents.17

Analysts were concerned about the validity of the combat exclusion policy and reminded policy makers that even the most cursory examination of recent combat experience revealed that all divisional troops could be called on at any time to fight as infantry. That was true at Kasserine Pass in North Africa, in the Battle of the Bulge, in Korea, and in Vietnam. According to this viewpoint, all armies implicitly viewed all of their soldiers except medical personnel as infantrymen. But that notion was becoming outdated. Martin Binkin has contended that "with the growing sophistication of weapons, you can't hand a cook or a clerk a Dragon [an antitank weapon] and send him up there. The only soldiers who will know how to use that weapon are the ones who have spent time training to use it." Still, regardless of the complexity of the equipment, soldiers on the ground were the only ones capable of seizing terrain from an enemy and holding it.18

Although U.S. forces sustained relatively few casualties in the Persian Gulf, the combat exclusion policy did not protect women from being among them. Women died while performing their duties just as men did. The Iraqi missile that destroyed a U.S. Army barrack in Dhahran, 200 miles from the Kuwaiti border, killed 3 women along with 25 men. Of the other 2 female soldiers killed in action, 1 died in a helicopter crash and the other in an antipersonnel mine explosion. Nineteen women were wounded in action, while 2 were taken prisoner of war. Three women died in nonbattle deaths and 13 suffered nonbattle injuries.19

S. Sgt. Tatiana Dees of the 92d Military Police Company out of Baumholder, Germany, became the first female nonbattle fatality in DESERT SHIELD. On 7 January 1991 she fell from a pier at the port city of Ad Dammam and drowned. She had been on patrol with another military police officer when she noticed an unknown person atop a crane photographing the port. Dees stayed to help after the local police arrived. Looking upward, unaware of the edge of the pier, she accidentally fell into the water. She was pulled out, but attempts to revive her

212

failed. Dees was 34 and the mother of a seven-year-old daughter and a son aged five.20

Another woman, Sgt. Sheri L. Barbato, worked as a records keeper in a vehicle maintenance unit of the 1st Cavalry Division (Armored). Her unit crossed the border into Iraq on the opening night of the fighting. Barbato later remembered thinking, "I didn't think women were supposed to get this close to the front lines." Thereafter, she was unconvinced of the viability of the exclusion policy. "There wasn't anything over there that happened to the guys that didn't happen to me," she said. "There were times when I would have welcomed the opportunity to fight back."21

Lt. Phoebe Jeter, "the first female Scudbuster," led a platoon of fifteen men assigned to a Patriot missile control team. She identified incoming Scuds, ascertained their location on a computer screen, and gave her men orders to destroy them. Her job entailed a great deal of pressure: If she did not destroy the Scuds that she saw on her screen, they could land on her base. Jeter had trained for three years in her assignment. As a result of her performance, she became the first woman in her battalion to earn an Army Commendation Medal while in Saudi Arabia.22

Sgt. Barbara Bates, 28, a meteorologist, was the sole woman serving with more than 700 artillerymen in a forward-based self-propelled howitzer artillery unit of the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized). Bates had a noncombat specialty but was supporting a combat unit. As long as her assigned duties matched her noncombat specialty, her assignment fell within Army policy. She provided the combat troops with swift, precise readouts of local winds, temperature, and other conditions that could make the difference between a killing shot and a wasted round. Combat related or not, Bates was in as much danger as the male soldier standing beside her firing the howitzer. "When the shells start coming downwind, I will be counting on my flak jacket for protection, not my MOS," she laughed.23

Sgt. Bonnie Riddell, a 27-year-old military policewoman from Fort Hood, Texas, spent her nights on perimeter duty. Like other guards she worked thirteen-hour shifts on a sandbagged observation post, which she shared with a male soldier. She carried a .45-caliber pistol at her hip, had an M16 rifle at her side, and manned a light machine gun. Riddell told a reporter who interviewed her while on duty that she was nervous and scared, but added: "If it happens while I'm sitting here, and it's a question of me or them, it's going to be them."24

The 24th Support Battalion (Forward), 24th Infantry Division, was the most forward-deployed American supply battalion in Saudi Arabia. Women comprised nearly one-quarter of the battalion's 400 troops. The battalion kept tank crews and infantry supplied with food, fuel, medicine, spare parts, and ammunition. To accomplish that, male and female soldiers of the 24th drove trucks and water and gas tankers, manned radios, and stood guard. Both men and women slept with their M16s "right next to us, like part of our bodies." Conditions in the desert were

213

A Military Policewoman on Patrol, as depicted in the painting "Patrol

Duty in Kuwait City"

tough, and the women complained no less than the men. But everyone, men and women alike, did the work they had to do.25

The American public saw female troops working side by side with men in the desert on the network news. A woman briefed General Schwarzkopf nightly with the latest military intelligence. Interviewers talked to women who fixed the engines of fighter jets, drove trucks, piloted supply planes, commanded communications centers, stood guard duty, tracked ships and planes on radar, served in secret intelligence units, and performed surgery in field hospitals. They learned that a woman led a company of Chinook helicopters into Iraq on the first day of the ground war.26

Although women could not fly combat aircraft during DESERT STORM, they engaged in many activities that exposed them to the same risks as men. Female helicopter pilots, while not participating in direct combat, flew into combat zones to move food, fuel, and soldiers around the battlefield and to evacuate wounded soldiers. Three percent, or 380, of the Army's 13,650 active-duty pilots were women.27

214

The death of Maj. Marie Rossi, a helicopter pilot interviewed by CNN shortly before her aircraft crashed returning from a supply mission, became a well-publicized tragedy. Rossi, a pilot with the XVIII Airborne Corps, was one of the first female soldiers over the border into Iraq when she led her company of Chinook helicopters in supplying ammunition to combat troops. "What I'm doing is no greater or less than the man who is flying next to me or in back of me," she said during the interview. Major Rossi died with her three crew members when their Chinook crashed into an unlit microwave tower during bad weather the day after the cease-fire.28

Two female soldiers were taken prisoner by the Iraqis. Both women received considerable media attention, but Army Spc. Melissa Rathbun-Nealy became a media-inspired instant celebrity because she was captured first and held longer. Rathbun-Nealy, aged 20, and her partner Spc. David Lockett, both of the 233d Transportation Company, were wounded and captured by the Iraqis on 30 January.

As the first American female prisoner of war in fifty years, Rathbun-Nealy rapidly captured the public's imagination. Her company had been in Saudi Arabia since October. She, Lockett, and two other soldiers went to retrieve two heavy equipment vehicles being repaired near Dhahran. On 30 January the vehicles were ready, and the four soldiers set out from Dhahran with maps to return the trucks to their unit. They passed through an intersection, failed to turn west as directed, and mistakenly headed toward R'as al Khafji, where heavy fighting was going on. The two trucks passed through several Saudi checkpoints. As they approached R'as al Khafji, they came under fire. The driver of the second truck made a U-turn and retreated. Looking back, the soldiers saw the lead truck stuck in the sand. Enemy troops quickly surrounded the vehicle. Rathbun-Nealy and Lockett were held as prisoners of war in Baghdad for over a month before they were released with other U.S. prisoners on 4 March 1991.29

The second American female soldier captured by the Iraqis was Maj. Rhonda L. Cornum. Cornum, 36, was an Army flight surgeon with an Apache attack helicopter battalion. She had volunteered for a helicopter search-and-rescue mission and crashed behind enemy lines. Five of the helicopter's eight crew members were killed. Cornum was listed as missing, and it was not known that she was a prisoner until a day or so before her release.30

Congresswoman Patricia S. Schroeder of Colorado believed that after the war the American voter was willing for the first time to accept the lifting of the ban on servicewomen in direct combat. Other observers claimed that DESERT STORM was not a fair test of the capabilities of female soldiers under pressure, because the war was short and casualties low. So, for some, questions remained about the performance of female soldiers over the long haul.31

In an Associated Press poll on women in combat, conducted between 13 and 17 February 1991, with a sample of 1,007 adults from forty-eight states, 56 percent responded that women in the armed forces should par-

215

ticipate in the war and 39 percent believed they should not. While 45 percent would not have objected to women from their family participating, 50 percent did not want to see a female family member deploy as a soldier. This contrasted substantially with the 22 percent who would have objected to a male member of their family fighting in Southwest Asia. Although 35 percent believed men and women were equally suited for combat, 61 percent believed men were better qualified. Thirty-one percent believed it was acceptable to send women with young children to the Persian Gulf; 64 percent found that unacceptable. Only 28 percent thought it was unacceptable to send young fathers, and 68 percent believed it was acceptable.32

Charles Moskos observed that female officers wanted the combat exclusion policy abolished, because it inhibited their careers, but that enlisted women felt differently.33 The difference of opinion may have been due to education levels. The more education women received, the more they believed in equal rights. The vast majority of Army officers had at least bachelor's degrees, and many had higher degrees or planned to pursue them. Most enlisted women had high school diplomas, although many planned to attend college in the future.34

Due to the professionalism with which female soldiers did their jobs in the war, Secretary of Defense Richard B. Cheney stated that he "would not be surprised" if women's combat roles were eventually expanded. In fact, during the last week of May 1991 the House of Representatives approved a military budget bill with a provision removing the legislative language that had precluded women in the Navy, Marines, and Air Force from flying aircraft in combat missions. As the Army patterned its combat exclusion policy on the legal restrictions pertaining to the other services, it could follow their lead and open direct combat flying positions to women. Army women themselves were divided on whether they wanted to engage in direct combat, but the vast majority believed they should be given the opportunity to choose.35

Reserve-component recruitment showed a significant overall decline. Army National Guard recruiters achieved 72 percent of their goal and the Army Reserve reached 77 percent in the first quarter of 1991. During the

216

crisis the Army's "Stop Loss" program held soldiers who might have completed terms of service, many of whom would have gone into the reserves.37 In addition, during the first months of DESERT SHIELD reserve units were prevented from recruiting once they were activated, so activated units could not fill vacancies through recruitment. Furthermore, the recruiting services were limited with respect to the units and positions against which they could recruit people. Analysts realized that this practice would create a long-term shortage for reserve units once hostilities ceased and units went home. So the policy was reversed in late November, when reasons for the recruitment shortage became clear. While new enlistees did not deploy with the unit, they were scheduled for training and would be available to man the unit when it returned.38

The Army required both single and dual military parents to set up care arrangements in the event that they were deployed. Single and dual military parents maintained up-to-date family care plans that included all the provisions necessary for the care of dependents when the soldier deployed, such as powers of attorney for temporary and long-term guardians, notarized certificates of acceptance as guardians, identification card applications, and signed allotment forms or other financial support documentation. Regulations required annual review and validation of the plans. If a commander found a plan to be inadequate, the soldier had to fix it or face separation from the service. The same provisions applied to members of the Selected Reserve, but individual ready reservists did not have to complete the necessary paperwork until activated. Then they either developed an acceptable family care plan or faced separation.40

Inevitably, some plans proved unrealistic, and others became outdated because of circumstances beyond the soldier's control. Designated guardians became ill or injured and were unable to care for the children as planned. Some guardians discovered that the strains of caring for dependents were too much for them physically or emotionally. Longer deployments resulted in a higher number of failed plans.41 The Army could do little about that except continue to replace soldiers who could not remedy family care problems.

When a plan failed, Army regulations required that the soldier attempt to arrange alternate care while remaining on duty. That was not always possible. During the Persian Gulf war the Army permitted soldiers to return home for a maximum of thirty days to resolve family care problems. The Army voluntarily or involuntarily separated any soldier who could not establish a workable alternative plan within that time.42

217

Family Assistance Center, Fort Riley, Kansas, where volunteers provided

information and support to the families of the 1st Infantry Division soldiers

during the Persian Gulf crisis

Throughout the crisis, the majority of readiness problems occurred in units unaccustomed to regular deployments. More soldiers in these units turned out to be nondeployable or lost deployment time because of outdated or unrealistic family care plans. In units that practiced deployment regularly, single and dual military parents were generally fully ready to go. The results indicated that the best way to ensure realistic plans and the deployability of the force was to test readiness in all units regularly. After all, the best way to discover if something worked properly was to try it. The maximum number of Forces Command and U.S. Army, Europe, soldier family care plans that proved to be inadequate at any one time was 124. In many of those cases solutions were found in time for the soldiers to deploy.43

Studies showed that soldiers who knew that their families experienced difficulties back home performed less efficiently and were more vulnerable to stress-induced mental and physical illness and accidents. Family assistance centers and informal family support groups organized at the unit level helped maintain the morale and efficiency of the deployed

218

force.44 The 166 Army-sponsored assistance centers functioning in the United States proved particularly valuable to the families of soldiers who went to Southwest Asia. In areas that did not have assistance centers, informal volunteer-run support groups provided information and support to the families of soldiers in the Persian Gulf. Those organizations helped with problems ranging from monetary and legal difficulties through medical and psychological illnesses.45

Press reports focused on the various stresses and strains with which the families of soldiers coped. Some families handled the situation better than others. Invariably their experiences were as different as the families themselves. Supply Spc. Michele Brown, a 21-year-old single mother, went to Saudi Arabia with the 202d Military Intelligence Battalion. Brown left her 3-year-old daughter with her own mother. While in the Persian Gulf, Brown learned that her daughter was hospitalized with asthma. "It's hard being a single parent and going to war,' said Brown. "I don't want to be here."46

Married soldiers had their own problems. Some young wives who remained behind while their husbands deployed had never driven a car, paid a bill, or balanced a checkbook. Young couples without children sometimes made no arrangements to deal with a deployment. Young wives were left without access to bank accounts. Some soldiers put their cars in unit lockups when they left because they did not want their wives to drive them. The women were left with no transportation. One soldier locked his foreign-born wife into their trailer with three weeks' groceries and no plan for a longer deployment. The Inspector General's Office at Fort Hood, Texas, estimated that 28 percent of the young wives of deployed soldiers left the Fort Hood vicinity and returned "home" to live with relatives for the duration of the deployment. Fort Stewart, Georgia, and Fort Bragg, North Carolina, reported similar developments.47

More than 14,000 women gave birth without the support of their husband's physical presence. Many spouses with infants and small children felt like single parents and had problems coping with confused and frightened children. Some schools noticed increased truancy rates as the children struggled to deal with their fears. Some spouses who stayed behind developed stress-related illnesses, from insomnia through migraines, ulcers, and changes in weight.48

Family assistance centers and support groups gave the families of deployed soldiers the information, advice, and emotional support they needed to help deal with those problems. Those organizations also provided critical information to guardians unfamiliar with standard military services and procedures. For example, some guardians had trouble obtaining military identification cards, which gave the children of military parents access to military services and facilities such as medical care. Although by law military dependents were entitled to medical care, some guardians had trouble obtaining it for the children in their care.49

219

The dependents of Army Reserve and Army National Guard personnel had special problems. As of July 1990, only 22 percent of reserve and 21 percent of guard personnel had pre-enrolled their family members in the Defense Enrollment and Eligibility Reporting System, the program that automatically entitled them to medical care. The paperwork necessary for enrollment often could not be accomplished during the mobilization period.50

Soldiers who went to the Persian Gulf from Europe had unique family care problems. Often, the guardians designated by family care plans lived in the United States. In many cases the deployment came so fast that soldiers did not have time to escort dependents home to the United States and return to their units in Europe in time to deploy with them.51

Not every family needed an assistance center or a support group. Some spouses accepted and enjoyed the new challenges they faced. Optometrist and Washington State Senator Mike Kreidler, an Army Reserve lieutenant colonel with the 6250th U.S. Army Hospital, was called to active duty for three months early in 1991. According to state law, Kreidler had to give his county commissioners a list of three candidates qualified to carry out his senatorial responsibilities while he was gone. One of the names on his list was that of his wife. Mrs. Kreidler was surprised when chosen to fill in for her husband. She had never been interested in "becoming a public figure and inhabiting the limelight." But she accepted because "she knew how much politics and serving in the legislature meant to her husband, and he needed to be sure that the person inhabiting his position was someone he could trust, someone who shared common views on legislative matters." Enjoying the work more than she expected, she began considering entering politics herself.52

The deployment of single and dual military parents caused a great deal of controversy and comment among the press and the public. The concern was inevitably reflected in Congress. Should the services deploy single and dual military parents to a combat area? The image of mothers kissing small children good-bye to march off to war, and the specter of large numbers of war orphans, bothered many politicians as well as their constituents. Congress responded to public concern with several different proposals, all seeking to limit the Defense Department's ability to send parents of dependent children to a combat zone.

Senator John Heinz of Pennsylvania proposed a nonbinding resolution asking the Department of Defense to consider a policy allowing single parents and one member of dual military parents a noncombat zone duty assignment. The bill sponsored by Congresswoman Barbara Boxer of California would have limited the military's ability to send single parents and both military parents into a combat zone. Congressman E. Clay Shaw, Jr., of Florida proposed that mothers of children under six months of age not be assigned to an area subject to hostile fire. Others in Congress who expressed public concern and who proposed changes in

220

Department of Defense assignment policies included Senator Herb Kohl from Wisconsin and Congresswoman Jill L. Long of Indiana.53 The Department of Defense, opposed to all limitations on its ability to deploy soldiers overseas, claimed such restrictions were not needed given the volunteer nature of the force and the overall success of the family care plans.54 Because large numbers of casualties did not occur, the political pressure to resolve the issue of the deployment of single parents to a combat zone was minimal, and the issue remained unresolved.

The war in Southwest Asia resulted in the deaths of three soldiers with custody of minor children, one woman and two men. In each case, the soldier's family care plan had designated long-term guardians. Two of the designated guardians accepted the children in question. In the third case the soldier's family petitioned a court to make alternative arrangements.55

Another issue revolved around the amount of leave time granted to female soldiers after giving birth. Several highly publicized episodes involving maternity leave led to criticism of existing Army policies. Two Pennsylvania reservists gave birth shortly after receiving their call-up papers. Although one had a Caesarean section, she was originally allowed only a fifteen-day delay. The other initially received a ten-day leave.58 In both cases the Army resolved the mistake made at the Reserve Call-Up Center and granted the women the standard amount of time they were entitled to by regulation.59

Regulation allowed female members of the Regular Army, Army National Guard, and Army Reserve a recovery period after birth of forty-two days, after which they had to return to duty or leave the service. The situation encountered by the two Pennsylvania reservists mentioned above indicated a problem in the Individual Ready Reserve call-up process. The Individual Ready Reserve is a category into which the Army placed active-duty soldiers unable to perform their duties because of health or family problems but who had an unexpired term of service. Both women had left the Regular Army and entered the Individual Ready Reserve because of their pregnancies.60 In the event of

221

a call-up, the very factors that placed the soldiers into the reserve often made them unavailable for deployment.61 The call-up process confused many reservists; however, if they could supply a doctor's note describing them as unfit for duty because of a medical condition, they were granted leave. Approximately 430 individual ready reservists eventually obtained leave from their commands through the proper channels due to documented health problems.62

Reserve soldiers ordered to duty while in their first trimester of pregnancy were activated but not deployed. They were assigned duties in the United States. The Army dealt with soldiers in their second and third trimesters on a case-by-case basis. Usually the Army retained them with light or even part-time duty. Soldiers in Saudi Arabia found to be pregnant by military physicians were sent to their home base for prenatal care and continued duty. Conditions in the Persian Gulf, from the climate to the weight of chemical protective gear worn by all soldiers, did not meet Army standards for the assigned duties of pregnant soldiers.63

Army policy allowed eligible soldiers to apply through their units for sole survivor status, which would place them in assignments in the United States or another noncombat area. The services allowed the soldiers to refuse sole survivor status if they desired.65 The Army believed the policy was fair and that it worked well. Once again, the low level of casualties in the Persian Gulf war prevented this dilemma from remaining in the forefront of public concern.

222

other dialects, such as Syrian and Egyptian; an Iraqi dialect video crash course in military terminology; and an Iraqi dialect dictionary. The video and dictionary were sent to Saudi Arabia to help intelligence officers already in the field.66

The U.S. Total Army Personnel Command found several Arabic linguists at Forts Campbell (Kentucky), Stewart (Georgia), and Devens (Massachusetts), as well as three serving in non-language positions in Germany and two in Hawaii.67 On 14 January the retraining of about 160 high-caliber German, French, Polish, and Chinese Mandarin linguists began at four sites. Those people were scheduled to be available for deployment to Southwest Asia by mid-July.68

The Army also experienced shortages of truck drivers, helicopter pilots, and medical personnel. Additional truck drivers came from the Individual Ready Reserve, and volunteer and involuntary retirees were used as helicopter pilots. The Army also called involuntary retirees to fill medical positions. The twelve-week initial entry training requirement kept the Army from rapidly filling critically needed positions, which required specialized training in medicine, dentistry, and law. That requirement stipulated that no soldier was legally available for deployment overseas before completing a mandatory twelve-week basic training course that taught military survival skills. Although military planners did not seriously consider removing the prohibition, they wanted to modify the requirement so prospective reservists specializing in those fields could undergo their military survival training immediately after joining the Army Reserve.69

Civilians served in temporary assignments that ranged from 30 days with the Corps of Engineers to 179 days in the Army Materiel Command. Those directly supporting a specific military unit served a six-month temporary tour, while those supporting operations in general but not linked to a specific unit served shorter temporary stints or a one-year unaccompanied tour, based on the nature of the assignment and the commander's discretion.71

The Engineers and the Army Materiel Command deployed the most civilians. At first, only Forces Command had a civilian personnel office in

223

Riyadh. Other Army commands sent civilians to the Persian Gulf but provided no in-theater personnel assistance for them. Eventually, the Army Materiel Command established a position for a civilian personnel adviser in Dhahran, and the Corps of Engineers borrowed a Training and Doctrine Command employee to fill that role. But the Department of the Army provided no overall coordinator and troubleshooter to handle such issues as pay and allowances, benefits, entitlements, training, equipping, and processing with Army Central Command.72 Although the vast majority of Army civilians performed commendably, a great deal of time, confusion, and aggravation could have been avoided had the deployments been better planned. For example, at the height of civilian deployment the Army belatedly discovered that many civilians had been sent without dental x-rays, a main source of identification in the event of mass casualties.

In retrospect, some analysts thought that future deployments would work better if the use of civilians in specific functions was incorporated into Army plans. That way the functions and the support provided for them would be underpinned with authorization documents, equipment, and personnel slots and training. Civilian personnel positions that were potentially deployable would be clearly designated as such, and the occupants of these positions would be required to meet physical and mental standards comparable to those for military personnel in similar positions.73 That did not happen in the Persian Gulf war. Although a system existed for designating civilian positions "emergency essential," very few of the people deployed were in positions so designated.74

The Army also discovered the need for training programs for civilians in positions identified as deployable so that they could maintain and operate protective chemical equipment and survive on the battlefield if necessary. Moreover, the Army had to realign the benefits and pay of civilian positions designated "emergency essential" so that those civilians sent into a combat theater would get the same type of consideration, including medical, as soldiers.75 Finally, an Army command had to serve as the authority for the cross-leveling and assignment of civilians to support deployments in a manner similar to that of military personnel. Such action could have prevented problems such as the one that occurred when the commander of U.S. Army, Europe, refused to release a civilian safety officer for duty in Saudi Arabia despite an identified need for one there. Command-and-control issues had to be rectified before Army civilians could be used to full advantage.76

Contractor personnel and Red Cross workers also deployed to Southwest Asia to work with the Army. At least 3,000 contractor employees were in the theater during the peak deployment in February. Those men and women went there to service and maintain the complicated equipment used by the Army. For example, contractor capability helped maintain an aircraft availability rate of near 90 percent in the desert. Although the Army assumed minimal responsibility for those people, the issue of the extent of Army responsibility needed clarification for future

224

deployments. Red Cross workers-men and women alike-also played a part, making sure that emergency messages concerning life-and-death situations at home reached the troops.77

Active-duty and reserve soldiers who decided to apply for objector status were free to do so, but the Army required them to deploy with their units while it considered their applications. Those who submitted applications were often assigned duties that provided a minimum practicable conflict with their asserted beliefs. Between August 1990 and April 1991 the Department of the Army Conscientious Objector Review Board reviewed 131 requests from soldiers in the Regular Army and 10 from the Army Reserve and Army National Guard. The board approved 89 of the above cases. Seven of the soldiers withdrew their requests.79

Several reservists and active-duty soldiers who declared themselves conscientious objectors received a great deal of press coverage. Spc. Stephanie Atkinson was the first reservist who refused to report, claiming objector status. Atkinson held that she had joined the Army Reserve for the educational benefits and claimed that she had never really considered

225

the possibility of being sent into a combat zone. She received a notice to report to Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, for training with her unit, the 300th Adjutant General Company (Postal), in October 1990. The unit was scheduled to leave for Saudi Arabia on the twenty-third. When shedid not report for duty, she was apprehended and placed in detention. Although she claimed objector status, the Army did not recognize her as such because she had not followed regulations in filing her claim and had refused to deploy with her unit while her claim was being considered. Wanting to avoid a long and expensive court-martial, the Army released her from her Illinois unit under "other than honorable conditions" in early November.80

A Black Muslim at Fort Campbell claimed objector status, citing his religion, which forbade him to kill fellow Muslims. A Department of Defense spokesman stated that about 2,700 followers of Islam served in all the U.S. military services and that Muslim soldiers had deployed to Saudi Arabia. One such soldier said that he was "defending the birthplace of his religion" and that he had no problems serving in the allied forces against Iraq. These and similar cases underscored the persistence of the issue despite the transition to an all-volunteer force.81

The public showed its support for the troops in many and varied ways. Universities and colleges gave tuition refunds and "incomplete" or "withdrawn passing" grades to deploying students. Large and small businesses provided Army Reserve and Army National Guard employees supplemental salaries, designed to fill the gap between civilian and military paychecks. Chambers of Commerce raised money via bake sales, book sales, and rodeos to send care packages and Christmas stockings to soldiers in the Persian Gulf. Pizza parlors provided free pizzas and soda to family support centers and support groups. Large corporations, such as Walmart, Nabisco, Wendy's, and Proctor and Gamble, donated material for care packages. The National Football League sent 700 footballs and 20,000 pounds of jerseys, towels, hats, sun visors, sunglasses, sweatbands, and trading cards to the troops in the desert.83

226

|

|

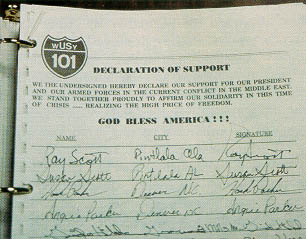

| A Declaration of Public Support. Representatives of a Chatanooga radio station present to Secretary of Defense Richard B. Cheney the signatures of 30,000 local residents in support of Persian Gulf operations. |  |

The outpouring of appreciation continued even after the soldiers came home. Soldiers coming home from Vietnam had been greeted by a bewildering combination of hostility and neglect. Those who returned from the Persian Gulf found themselves starring in victory parades and celebrations. Perhaps the abundant support represented a clumsy public apology to the veterans of Southeast Asia. Whatever the case, for the first time in over a generation American servicewomen and men were all, without exception, considered heroes.

227

Yeosock in the Victory Parade, as depicted in the painting "Desert

Storm NYC Homecoming Parade"

Notes

1 Joseph L. Galloway, "Life on the Front Lines," U.S. News & World Report (24 December 1990): 28-37, Leslie Dreyfous, "From Teens in Vietnam to Parents in the Gulf," Philadelphia Inquirer, 20 Feb 91, p. 11.

2 Ibid.; Tom Morganthau et al., " The Military's New Image," Newsweek (11 March 1991): 50-51.

3 Robert L. Phillips and John D. Blair, "The All-Volunteer Army: Fifteen Years Later," Armed Forces and Society 16:3 (Spring 1990): 329-50; Fred Tasker, "The Military Gets a New Identity," Orange County Register, 27 Sep 90, p. J1. For a general background on the establishment of the all-volunteer Army, see Robert K, Griffith, Jr., The U.S. Army's Transition to the All-Volunteer Force, 1968-1974 Army Historical Series (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, forthcoming).

4 Doug Bandow, "The Volunteer Army Represents America," Wall Street Journal, 27 Nov 90, p. l6; Ronald Brownstein, "Volunteer Force: Is It Truly Fair?," Los Angeles Times, 6 Dec 90, p. 1.

5 David Gergen, "America's New Heroes," U.S. News & World Report (11 February 1990): 5.

6 Juan Williams, "Race and War in the Persian Gulf: Why Are Black Leaders Trying To Divide Blacks From the American Mainstream?," Washington Post, 20 Jan 91; "Representative Conyers Says Blacks Are Victims of Economy," Washington Post, 14 Feb 91, Information Paper, Maj Plumer, DAPE-HR-L, 19 Mar 91, sub: Racial/Ethnic and Gender Breakdown by CMF.

7 Williams, "Race and War in the Persian Gulf."

8 David Evans, "Some Urge Draft To Ensure a War Is Classless Struggle," Chicago Tribune, 29 Nov 90, p. 1.

9 Ibid.

10 Robert K. Landers, "Should Women Be Allowed Into Combat?," Congressional Quarterly's Editorial Research Reports 2:14 (October 1989): 577,

11 Ibid.

12 Information Paper, Maj Plumer, DAPE-HR-L, 19 Mar 91, sub: Equal Opportunity Climate, Information Paper, Maj Etchieson, DAPE-HR-S, 19 Mar 91, sub: Women in SWA.

13 MS, Women's Research and Education Institute, Women in the Military 1980-1990 [Washington, D.C., 1991], p. 9.

14 Ibid., p. 10; Statement by Lt Gen William H. Reno, Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, U.S. Army, before the Subcommittee on Military Personnel and Compensation, Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, 102d Cong., 1st sess., 7 March 1991.

15 MS, Women in the Military 1980-1990, p. 10; Landers, "Should Women Be Allowed Into Combat?," p. 572.

16 Information Paper, Plumer, sub: Equal Opportunity Climate; Information Paper, Etchieson, sub: Women in SWA, Landers, "Should Women Be Allowed Into Combat? ' " p. 572 , MS, Women in the Military 1980-1990, pp.9-10.

17 Information Paper, Plumer, sub: Equal Opportunity Climate; Information Paper, Etchieson, sub: Women in SWA, Executive Summary, Capt Buckmaster, TAPCPLF, 11 Apr 91, sub: REDCAT Data on DESERT SHIELD/STORM Casualties, Executive Summary, Lt Col Roberts, CMAOC, 11 Apr 91, sub: DESERT STORM Demographics.

18 Landers, "Should Women Be Allowed Into Combat?," pp. 578-80.

19 Information Paper, Etchieson, sub Women in SWA; List, Mal James C. Trower, TAPC-MOB, 18 Apr 91, sub: In Response to the DCSPER Query Regarding Female KIA/NBD and on the Civilian Death.

20 Memo for the Deputy Chief of Staff of Personnel, 16 Jan 91.

21 Jon Nordheimer, "Women's Role in Combat: The War Resumes," New York Times, 26 May 91, p. 28.

22 Jeannie Ralston, "Women's Work," Life (May 1991): 56.

23 Colin Nickerson, "Combat Barrier Blurs for Women on the Front Line," Boston Globe, 13 Nov 90.

24 Tony Clifton, "You're Here. They're There. It's Simple," Newsweek (12 November 1990): 28.

25 Quote from Ibid. Mariam Isa, "Some Female Soldiers Want Out," Washington Times, 27 Sep 90, p. 1 James LeMoyne, "Army Women and the Saudis: The Encounter Shocks Both," New York Times, 25 Sep 90, P. 1.

26 Ibid.

27 Eric Schmitt, "Head of the Army Sees Chance of Female Fliers in Combat," New York Times, 31 May 91.

28 Joseph F. Sullivan, "Army Pilot's Death Stuns Her New Jersey Neighbors," New York Times, 7 Mar 91, p. Bl.

29 Mary Radigan, "Army Details How Melissa Got Lost, Was Captured by the Iraqis," Grand Rapids Press, 25 Feb 91, p. A8.

30 Washington Post, 6 Mar 9 1.

31 Lorraine Dushy, "Combat Ban Stops Women's Progress, Not Bullets," McCall's Magazine (May 1990): 26.

32 Associated Press Gulf Poll, 20 Feb 91.

33 Nordheimer, "Women's Role in Combat"; Landers, "Should Women Be Allowed Into Combat?," p. 2.

34 MS, Women in the Military 1980-1990, p.2.

35 Schmitt, "Head of Army Sees Chance of Female Fliers in Combat."

36 Statement by Lt Gen William H. Reno, Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, U.S. Army, before the Subcommittee on Military Personnel and Compensation, Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, 102d Cong., 1st sess., 7 March 1991, p. 8.

37 Ibid., JULLS Long Rpt, JULLS 51760-11293 (00028), Lt Col Dennis Winn, DAPE-MPA, 21 May 91, sub: Recruiting During Hostilities.

38 Ibid. DESERT STORM After Action Rpt, Lt Col Winn, DAPE-MPA, 23 May 91.

39 Information Paper, Lt Col (Chaplain) Jack Anderson, DAPE-HR-S, 19 May 91, sub: Single Parents/Dual Military Couples.

40 Information Paper, Lt Col Anderson, 11 Mar 91, sub: Family Care Plans AR-600-20.

41 Barbara Kantrowitz and Mike Mason, "The Soldier-Parent Dilemma: Which Comes First, Children or Country?," Newsweek (12 November 1990): 84.

42 Rick Maze, "Immediate Change in Family Policy Unlikely," Army Times, 26 Feb 91, p. 8.

43 Information Paper, Lt Col Theodore Parukawa, CFSC-AE-R, 24 Jan 90, sub: Soldier Deployability and Family Situation.

44 MS, Lt Col David J. Westhuis, Human Factors in Operation DESERT SHIELD: The Role of Family Factors, U.S. Army Community and Family Support Center, 9 Nov 90.

45 Bulletin 16-90, 28 Nov 90, Directorate of Public Affairs, Headquarters, Forces Command, Fort McPherson, Ga.

46 Eric Schmitt, "War Puts U.S. Servicewomen Closer Than Ever to Combat," New York Times, 22 Jan 91.

47 MS, Westhuis, Human Factors in Operation DESERT SHIELD: The Role of Family Factors, p. 9; Galloway, "Life on the Front Lines," pp. 28-37.

48 Ibid., Lara Marlowe, "Life on the Line," Time (25 February 1991): 36-38.

49 JULLS Long Rpt, JULLS 51669-84605 (00014), DAPE-HR-S, 21 May 91, sub: Secure ID Cards and Agent's Letters by Guardians.

50 JULLS Long Rpt, JULLS 5167l-64420 (00016), Maj Scott Howard, DASG-PSA, 21 May 91, sub: Reserve, NG DEERS Eligibility.

51 JULLS Long Rpt, JULLS 51671-10083, DAPE-HR-S, 21 May 91, sub: FCP, Single Parents, Dual Military Couples, NEC, Escorts, Guardians, OCONUS.

52 Bill Timnick, "Reservist Gave Senate Seat to Spouse During DS," The Ranger (Army Reserve Newsletter, Fort Lewis, Wash.), n.d.

53 Maze, "Immediate Change in Family Policy Unlikely," p. 8, Dana Priest, "G.I.'s Left 17,500 Children ," Washington Post, 15 Feb 91, p. 1: Washington Post, 20 Feb 91.

54 Ltr, Secretary of Defense Cheney and General Powell to George Mitchell, Majority Leader, U.S. Senate, 7 Feb 91.

55 Briefing to DCSPER, Lt Col Donald Pavlik, DAPE-ZX, 19 Mar 91.

56 Interv, Judith L. Bellafaire with Maj Marlene Etchieson and Lt Col (Chaplain) Jack Anderson, Apr 91.

57 "Personnel Service Support," in Getting to the Desert (Fort Leavenworth, Kans.: Center for Army Lessons Learned, n.d.), pp. 1-2.

58 "University of Penn Researcher Says Army Calls New Mothers to Duty Too Soon," Philadelphia Inquirer, 12 Feb 91.

59 Interv, Judith L. Bellafaire with Col Terrence Hulin, DAPE-HR, 14 Nov 91,

60 Katherine Seelye, "Called to Duty While in Labor," Philadelphia Inquirer, 6 Feb 91.

61 Discussion Paper, Chaplain Anderson, 13 Mar 90, sub: Single Parents/Dual Military Parents.

62 Hulin interview.

63 Etchieson interview.

64 AR 614-200, Assignments, Details, and Transfers: Selection of Enlisted Soldiers for Training and Assignment (1982), sec. IV 3-16.

65 Ibid.

66 Discussion Paper, Col Lipke, DAMI-Pll, 18 Mar 91, sub: Arabic Linguists in Support of DESERT SHIELD, Sfc. Tony Nauroth, "Arabic Linguists," Soldiers (May 1991): 18.

67 Executive Summary, Col Dabbieri, TAPC-EPL, 6 Mar 91, sub: Assessment of Arabic Linguists.

68 Memo, Lt Col Brooks, DAPE-MBI, for the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, 18 Jan 91, sub: Arabic Linguists Training Status.

69 JULLS Long Rpt, JULLS 51660-70986 (00006), CW03 R. L. Gray, TAPC-MOB, 21 May 91, sub. Twelve Week Initial Entry Training Requirement.

70 Deployment of Civilians, tab H, DESERT STORM Special Study Report, General Officer Steering Committee, 9 Jul 91 Interv, Judith L. Bellafaire with Pat Stepper, TAPC-CPF-S; Rpt of the DCSPER/PERSCOM/ FORSCOM Mobilization Lessons Learned Workshop, 1-3 May 91.

71 Rpt of the DCSPER/PERSCOM/ FORSCOM Mobilization Lessons Learned Workshop, 1-3 May 91; Memo, James L. Yarrison for Gen Vuono, 8 May 91, sub: DCSPERIPERSCOM/FORSCOM Civilian Personnel Lessons Learned Workshop.

72 JULLS Long Rpt, JULLS 51669-34892 (00013), Patricia Turk, CPMD-DSTF, 21 May 91, sub: Requirement for CP Advisor on Forward PERSCOM MOBTDA.

73 Memo, Yarrison for Vuono, 8 May 91, sub: DCSPER/PERSCOW FORSCOM Civilian Personnel Lessons Learned Workshop.

74 Deployment of Civilians, tab H, DESERT STORM Special Study Report, General Officer Steering Committee, 9 Jul 91.

75 Ibid.

76 Memo, Yarrison for Vuono, 8 May 91, sub: DCSPER/PERSCOM/FORSCOM Civilian Personnel Lessons Learned Workshop.

77 Ibid.; T. Sgt. Linda L. Mitchell, "American Red Cross in Combat," Associated Press wire service report, 6 Mar 91.

78 JULLS Long Rpt, JULLS 52063-28207 (00043), Maj Rob Kissel, DAPE-MBB-C, 21 May 91, Memo, Maj Gen Larry D. Budge, Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel (ADCSPER), through CSA, for Assistant Secretary of the Army (Manpower & Reserve Affairs) (ASA M&RA), 28 Jan 91, sub: Report to Congress on Basic Allowance for Subsistence.

79 Information Paper, Lt Col Horne, DAPE-MPA, 7 Feb 91, sub: Conscientious Objectors, Briefing, Lt Col Hamahan, DAPE-MO, 8 May 91, sub: Mobilization.

80 "Reservist Refuses To Go To Gulf," Washington Times, 12 Nov 90, p. 2.

81 Ibid., Quote from Information Paper, Maj (Chaplain) Esterline, DACH-PPOT, 21 Feb 91, sub: Islam and Conscientious Objection to War. Laurie Goldstein, "The Other Side of Mobilization: Those Who Don't Want To Go," Washington Post, 5 Sep 90, p. 22.

82 James Bennet, "How They Missed That Story," Washington Monthly (December 1990): 8.

83 MS, Public Affairs Office, 87th Maneuver Area Command, Birmingham, Ala.,

Home Front Efforts for OPERATION DESERT SHIELD, n.d.

page updated 7 June 2001

Return to the Table of Contents