The Korean War

(Narratives Extracted from CMH Commemorative Posters)

|

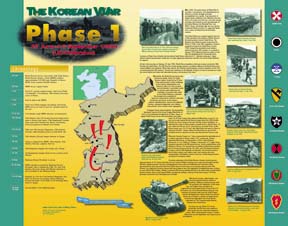

PHASE 1: 27 June-15

September 1950 (UN Defensive)

|

June 1950. The great victory of World War II was still a vivid memory. The demobilization of America’s wartime strength had been accomplished very rapidly. A growing fear of Joseph Stalin’s ambitions was reflected in the new terms iron curtain and cold war, but much energy and hope had focused on such developments as the United Nations, the Marshall Plan, and NATO. Korea, left divided after the war into the Communist North and the U.S.-supported South, was a source of tension but not immediate concern.

The United States was content largely to leave to a UN commission the problem of North Korea’s threatening stance toward South Korea. The Russians had withdrawn their troops from the North in 1948; at the UN’s suggestion, America recalled its troops from South Korea in June 1949, though leaving behind much military materiel and some 500 advisers. In a speech in January 1950 outlining American policy in Asia after the establishment of Communist China, Secretary of State Dean Acheson did not include South Korea within the U.S. "defensive perimeter"; those nations outside that perimeter would have to resist aggression themselves and then rely on the United Nations for support.

At four in the morning on Sunday, 25 June 1950, North Korea launched a full-scale invasion across the 38th Parallel into South Korea. The UN Security Council quickly passed a resolution calling on the North Koreans to cease hostilities and withdraw. When they refused, the Security Council passed a second resolution on the 27th recommending that UN members "furnish such assistance to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and restore the international peace and security in the area."

Meanwhile, the North Korean forces were advancing rapidly. Seoul, the South Korean capital, would fall by 28 June. These events posed a major challenge to the Truman administration and America’s allies, for if the invasion was not checked, a precedent would be set that could undermine the confidence of countries that relied on the United States for protection. The strength and availability of America’s armed forces, however, had been eroded by such factors as the massive postwar demobilization, uneven and neglected training, antiquated equipment, and, despite improvement, some residual racial segregation.

President Truman did not hesitate. He immediately instructed General of the Army Douglas MacArthur at his Far East Command headquarters in Tokyo, Japan, to supply South Korean forces with ammunition and equipment. On 26 June Truman then authorized MacArthur to use U.S. air and naval units against North Korean targets below the 38th Parallel, and the next day, seizing on the new Security Council resolution, he extended the range of those targets to include those in North Korea. He also authorized the use of U.S. ground forces to protect Pusan, South Korea’s major port. On 30 June, after MacArthur had gone to Korea to assess the situation, Truman authorized MacArthur to use all of his available forces to repel the invasion and blockade the Korean coast.

When the Security Council on 7 July recommended the establishment of a unified command in Korea, under a U.S. commander, Truman appointed MacArthur as Commander in Chief, United Nations Command. Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker, Commander, U.S. Eighth Army, assumed command of all UN ground forces, which included those of the Republic of Korea. U.S. ground forces available to MacArthur included the 1st Cavalry Division and the 7th, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions in Japan and the 29th Regiment on Okinawa. The divisions lacked a third of their infantry and artillery units, and existing units were understrength. Ammunition reserves were low, and training had been sacrificed to occupation duties.

Given the momentum of the North Korean advance and the general unpreparedness of U.S. forces when they arrived, General Walker’s strategy was to gain time through extended defensive delaying actions. The price of engaging the enemy with an inadequate force had been clearly demonstrated in early July when Task Force Smith, flown in from Japan as an advance element of the 24th Division, was attacked and had to retreat with heavy losses of men and equipment. In fighting that grew as fierce as many World War II battles, Walker’s combined UN forces gradually fell back to the south under constant North Korean pressure. But in early August Walker changed the strategy, ordering a final stand along a 140-mile perimeter around the now well-stocked port of Pusan.

With great courage, determination, and adroit movements between defensive positions, Walker’s combined troops held the perimeter into September. At the same time, the Eighth Army’s strength was augmented by mid-August by the arrival of the U.S. 2d Division, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, four battalions of medium tanks from the United States, and the 5th Regimental Combat Team from Hawaii. By the end of August a number of South Korean divisions had regrouped, and Great Britain committed its 27th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade from Hong Kong.

The stage was set. Under U.S. Army leadership, the UN force had checked a much larger but now somewhat weakened enemy. With reinforcements in place, General MacArthur by mid-September was ready to go on the offensive.

|

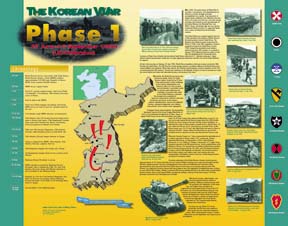

PHASE 2: 16 September-2

November 1950 (UN Offensive)

|

At the end of the first campaign of the Korean War, the UN Defensive, General Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief, United Nations Command, was ready to attempt to repel what had been the sustained advance of the North Korean People’s Army. Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker’s Eighth Army had been reinforced, its logistical support had solidified, and it had checked the enemy along a defensive perimeter west and north of Pusan. This next campaign, the UN Offensive, would be a story of stunning success.

The risk of success, however, was that it might provoke Communist China. But in mid-September 1950, Chinese military involvement was not a major concern for either General MacArthur or President Harry Truman. The focus was on breaking out from the Pusan Perimeter and engaging the North Koreans. MacArthur believed that the North Koreans’ deep penetration south into the Republic of Korea (ROK) made their forces vulnerable to an amphibious encirclement. His plan called for Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond’s separate X Corps—consisting of the 7th Infantry Division (augmented with 8,600 ROK troops) and the 1st Marine Division—to make an amphibious landing at Inch’on, a port on the Yellow Sea well behind enemy lines twenty-five miles west of Seoul. A force landing at Inch’on would have to move only a relatively short distance inland to cut North Korea’s major supply routes, recapture the South Korean capital, and block a North Korean retreat once the Eighth Army advanced northward from the defensive line at Pusan.

The landing at Inch’on was a considerable gamble. If the assault failed, MacArthur would be left with no major reserves and no prospect of immediate further reinforcement from the United States. But the landing, against light resistance, worked. Starting on 15 September when a battalion of the 1st Marine Division, covered by strong air strikes and naval gun fire, captured Wolmi Island just offshore from Inch’on, the two X Corps divisions steadily moved inland toward Seoul over the next two weeks.

Meanwhile, on 16 September the Eighth Army began its offensive. The ROK I and II Corps were positioned on the north of the Pusan Perimeter; the U.S. I Corps (composed of the 1st Cavalry Division, the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade, the 24th Infantry Division, and the ROK 1st Division) moved from the Taegu front; the U.S. IX Corps, including the 2d and 25th Infantry Divisions and attached ROK units, was poised along the Naktong River. Walker’s forces moved slowly at first, but by 23 September the envelopment threatened by X Corps and Eighth Army became clear, and the North Koreans broke to the north. Elements of X Corps’ 7th Division and of the 1st Cavalry Division, Eighth Army, linked up on 26 September just south of Suwon. Seoul was liberated the next day, and MacArthur returned the capital to President Syngman Rhee on 29 September. By the end of September the North Korean Army no longer existed as an organized force in the southern republic. The border along the 38th Parallel had been restored.

The question now was whether to cross the border. To do so would clearly risk raising tensions with China and the Soviet Union. But the North Koreans still posed a threat: some 30,000 troops had escaped from the South, and an additional 30,000 were in northern training camps. President Truman and the Joint Chiefs of Staff gave cautious initial approval. At the beginning of October the ROK I and II Corps crossed the 38th Parallel, moving up the east coast and through central Korea. On 9 October an all-out offensive began after the United Nations General Assembly voted for the restoration of peace and security throughout Korea, thereby tacitly approving the occupation of the North. On that day General Walker’s U.S. I Corps crossed the border on the west.

On 19 October the I Corps’ 1st Cavalry Division and the 1st ROK Division entered P’yongyang, the North Korean capital. On the 24th MacArthur ordered his commanders to advance as quickly as possible, with all forces available, so that operations could be completed before the onset of winter. The press of the Eighth Army in the west was relentless, as it sent separate columns north toward the Yalu River, each free to press forward independently. On the 26th an ROK regiment sent reconnaissance troops to the town of Ch’osan, thereby becoming the first UN element to reach the Yalu.

Meanwhile, General Almond’s X Corps had been withdrawn from combat to prepare for new amphibious landings, but this time on the east coast. The rapid advance of ROK forces above the 38th Parallel and the fall of Wonsan, North Korea’s major port, to the ROK I Corps on 10 October allowed the 1st Marine Division to make an administrative landing at Wonsan on the 26th; on the 29th the 7th Division landed unopposed at Iwon, eighty miles farther north. Adding the ROK I Corps to his command, Almond then attacked up the coast and inland toward the Yalu and the Changjin (Chosin) Reservoir, focusing on the industrial, communications, and irrigation centers of northeastern Korea. As one American newspaper put it, "Except for unexpected developments . . . we can now be easy in our minds as to the military outcome."

But then the unexpected did happen. Resistance stiffened in the last week of October in both the Eighth Army and X Corps zones. On the 25th an Eighth Army ROK unit near Unsan northwest of the Ch’ongch’on River captured a Chinese soldier. The extent of Chinese infiltration was not clear, but over the next eight days Chinese forces dispersed the ROK troops who had reached the Yalu, battered the 8th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division near Unsan, and forced the ROK II Corps to retreat. Time would quickly demonstrate that this was not just a temporary setback. The nature of the Korean conflict would now fundamentally change.

|

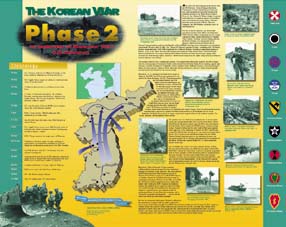

PHASE 3: 3 November 1950-24 January 1951 (CCF Intervention) |

The second phase of the Korean War, the UN Offensive, had been a story of relentless military success against the North Korean People’s Army. The capture of a Chinese soldier on 25 October 1950, however, marked a fundamental change in the nature of the conflict. When the presence in North Korea of Communist Chinese Forces (CCF) units was confirmed, there was much debate in the United Nations Command (UNC) and in Washington about China’s intentions, but that presence was quickly felt on the battlefield.

In the X Corps zone Chinese forces in late October had stopped a Republic of Korea (ROK) column advancing on the Changjin (Chosin) Reservoir. On 2 November the U.S. 7th Marines relieved the South Koreans and over the next four days broke through the Chinese resistance to within a few miles of the reservoir, at which point the Chinese broke contact. In the west, the Eighth Army fell back under attack to the Ch’ongch’on River, though the Chinese again broke contact after 6 November. By then three CCF divisions (10,000 men each) were estimated to be in the Eighth Army sector and two in the X Corps zone. UN pilots were also for the first time encountering Russian-made MIG–15 jet fighters.

After 6 November a comparative lull lasted for several weeks. Estimates of CCF strength rose through the month, but General Douglas MacArthur, the UNC commander, felt that the Chinese were not strong enough to launch an all-out offensive, particularly when North Korean's forces were battered and ineffective. He thus prepared to press on with his plans to reach the Yalu River. Moreover, MacArthur said, there was no other way to obtain "an accurate measure of enemy strength." Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker's Eight Army was to move northward through western and central Korea, while Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond's separate X Corps, now strengthened by the arrival of the 3d Infantry Division from the United States, was to move from northeastern Korea northwest to cut enemy lines of communication and support the Eighth Army. After taking time to improve his logistical support, Walker launched his offensive on 24 November. At first the Eighth Army encountered little opposition, but the next night the enemy launched a fierce counterattack in the mountainous terrain near the central North Korean town of Tokch'on. The X Corps, which had resumed its advance earlier, joined the planned attack on 27 November, moving slowly, but that evening a second enemy force, moving down the Chosin Reservoir, struck the 1st Marine Division and elements of the U.S. 7th Division.

It was clear that most of the enemy were Chinese, but the surprise was the size of the two attacking forces. By 28 November MacArthur had his "accurate measure" of the enemy’s strength: the Chinese XIII Army Group, with some 200,000 troops, faced the Eighth Army; the IX Army Group, with 100,000 men, faced X Corps. Both had slipped into North Korea from Manchuria largely undetected. On the 28th MacArthur informed Washington that "we face an entirely new war," and the next day he instructed General Walker to withdraw as necessary to escape being enveloped by the Chinese. He also ordered X Corps to pull back into a beachhead at the east coast port of Hungnam, north of Wonsan.

The main enemy attack in the Eighth Army zone was directed against the ROK II Corps. When the Chinese broke through the UN line, General Walker committed his reserves (the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division, the Turkish Brigade, and the British 27th Commonwealth and 29th Independent Infantry Brigades), but they failed to stop the repeated wave of enemy troops. Walker first withdrew south across the Ch’ongch’on River, suffering heavy casualties. The U.S. 2d Division fought a delaying action while other units regrouped in defensive positions near the North Korean capital of P’yongyang. On 5 December the Eighth Army fell back to positions about twenty-five miles south of that city, and by mid-December it had moved below the 38th Parallel to form a defensive perimeter north and east of Seoul, the South Korean capital. At the same time, in early December, MacArthur ordered X Corps to evacuate by sea to Pusan, where it would become part of the Eighth Army. December thus saw the loss of all UNC territorial gains in North Korea.

By this time the UNC included troops from fifteen countries, but the sense of crisis in the command was heightened by the death of General Walker in an auto accident north of Seoul on 23 December. Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway replaced him, arriving in Korea on 26 December. Ridgway was determined to maintain the existing line above Seoul, but on 30 December MacArthur told the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) that the Chinese could drive the UNC out of Korea unless he received major reinforcement. He also proposed air and naval attacks on mainland China and the involvement of Chinese Nationalist forces. None of his demands and proposals were accepted. Washington was not prepared to let the conflict in Korea escalate into a larger war. President Harry S. Truman’s more pressing concern was the global intentions of the USSR. The JCS told MacArthur to stay in Korea if he could but to prepare to withdraw to Japan if necessary.

On the other hand, despite a renewed enemy offensive that started on 31 December and saw the abandonment of Seoul on 4 January 1951, General Ridgway became increasingly convinced that his existing forces were sufficient. He noted that the Chinese did not aggressively push south after marching into Seoul and that North Korean forces ceased their offensive in central and eastern Korea by mid-January. He concluded that a rudimentary logistical system constrained enemy offensive operations to no more than a week or two. Tactically his goal was thus to "wage a war of maneuver—slashing at the enemy when he withdraws and fighting delaying tactics when he attacks." When General J. Lawton Collins, Army Chief of Staff, visited Korea, he agreed with Ridgway. "As of now," Collins announced on 15 January, "we are going to stay and fight."

As the third phase of the Korean conflict drew to an end, General MacArthur gave Ridgway unprecedented authority to plan and execute operations in Korea. Ridgway, in turn, was poised to return to the offensive.

|

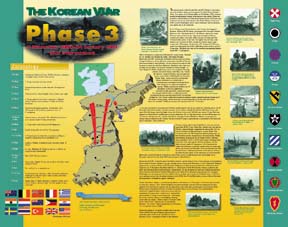

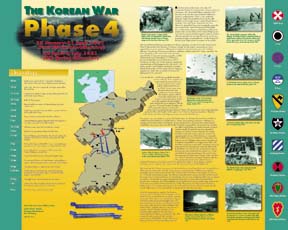

PHASE 4: 25 January-21 April 1951

(First UN Counteroffensive) |

As the third phase of the Korean War—the CCF (Communist Chinese Forces) Intervention— drew to a close on 24 January 1951, the United Nations Command (UNC) had come to the end of a series of tactical withdrawals. Starting in mid-December 1950, Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway's Eighth Army had fallen back from the 38th Parallel, first to the South Korean capital of Seoul, then to a line below Osan and Wonju. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond's X Corps had evacuated by sea on the east coast to Pusan, where it became part of the Eighth Army. All the territorial gains in North Korea of the earlier phases of the war had been lost. But General Ridgway was convinced the enemy lacked the logistical system to maintain offensive operations for any extended period, and he was preparing to begin a counteroffensive. This fourth phase of the war would largely shape the outcome of the conflict.

After two task forces had encountered little or no Chinese opposition in probes to the north, on 25 January General Ridgway launched Operation THUNDERBOLT, a larger but still cautious reconnaissance in force supported by air power. Resistance stiffened at the end of the month, but it gave way in the west by 9 February. The next day UN forces secured Inch'on and Kimpo airfield, and the U.S. I Corps neared the Han River. Meanwhile, on the central front, as the operation expanded, the X Corps met increasing opposition, and the Chinese struck back on the night of 11–12 February, driving back Republic of Korea (ROK) forces north of Hoengsong. But when four Chinese regiments attacked the crossroads town of Chip'yong-ni on the 13th, the U.S. 23d Infantry and the French Battalion conducted a successful defense for three days until the enemy withdrew. Ridgway regarded this valiant effort as symbolic of the renewed fighting spirit of his command.

In the west the U.S. I and IX Corps gradually seized the area up to the Han River, except for one enemy foothold between Seoul and Yangp'yong. By the 18th combat patrols confirmed that Chinese and North Korean troops along the entire central front were withdrawing. General Ridgway then began a general advance (Operation KILLER) by the IX and X Corps to pursue the enemy. By the end of the month the Chinese foothold below the Han River had collapsed. With the approval of General Douglas MacArthur, the UNC commander, Ridgway continued his attack north by launching Operation RIPPER on 7 March. The objective was a line designated Idaho just south of the 38th Parallel. On the night of 14–15 March, UN patrols moved into a deserted Seoul. By the end of the month Ridgway's troops had reached the Idaho line.

The question now was whether to cross the 38th Parallel again. On 20 March the Joint Chiefs of Staff had notified General MacArthur that President Harry S. Truman was preparing to announce a willingness to negotiate an end to the conflict with the North Koreans and the Chinese, an announcement that would be issued before any advance above the 38th Parallel. MacArthur preempted that announcement by issuing his own offer to end hostilities, but one that included a threat to cross the parallel. President Truman never released his statement, concluding, however unhappily, that perhaps MacArthur's ultimatum would pressure the enemy to the negotiating table. He also left the decision on crossing the 38th Parallel to tactical considerations. Consequently, when Ridgway received intelligence about enemy preparations for an expected spring offensive, he began a new attack, with MacArthur's approval, in early April. The objective was a line designated Kansas about ten miles above the 38th Parallel. By the 9th the U.S. I and IX Corps, and the ROK I Corps on the east coast, had reached that line, and the U.S. X Corps and the ROK III Corps were nearing it. The I and IX Corps then continued their attack beyond Kansas. At the same time, on 11 April, President Truman relieved MacArthur after the UNC commander said he would welcome the use of Nationalist Chinese forces since there could be "no substitute for victory" in Korea. Ridgway replaced MacArthur, and on 14 April Lt. Gen. James A. Van Fleet assumed command of the Eighth Army.

Eight days later four Chinese army groups and two North Korean corps began the enemy's spring offensive, attacking most heavily in the west, with a major focus on recapturing Seoul. Withdrawing in stages to previously prepared defenses several miles north of Seoul, General Van Fleet finally stopped the advance. On 15 May the enemy attacked again. Van Fleet had expected another advance on Seoul, but the brunt of the assault was in the east-central area. By repositioning units and using unrelenting artillery fire, he stopped the attack on 20 May after the enemy had penetrated thirty miles. To prevent the Chinese and North Koreans from regrouping, Van Fleet immediately sent the Eighth Army forward. Meeting light resistance, the Eighth Army was just short of the Kansas line by 31 May. The next day Van Fleet sent part of his force farther north, to a line designated Wyoming in the west-central area known as the Iron Triangle. By mid-June the Eighth Army was in control of both the Kansas line and the Wyoming bulge.

Given this strong defensive position, Van Fleet was ordered to hold and fortify it while Washington waited for the Chinese and North Koreans to offer to negotiate an armistice. The enemy in turn used this lull to regroup and to build defenses opposite the Eighth Army. The days settled down to patrols and small clashes. On 23 June, Jacob Malik, the Soviet Union's delegate to the United Nations, called for talks on a cease-fire and armistice. When the People's Republic of China endorsed Malik's statement, President Truman authorized General Ridgway to arrange the talks. After a series of radio messages, the first armistice conference was scheduled for 10 July in the town of Kaesong. The time of large-scale fighting was over.

|

PHASE 5: 9 July 1951-27 July

1953 (UN Summer-Fall Offensive 1951)

(Second Korean Winter) (Korea, Summer- Fall 1952) (Third Korean Winter) ( Korea, Summer 1953) |

Armistice talks began at Kaesong on 10 July 1951. North and South Korea were willing to fight on, but after twelve months of large-scale but indecisive conflict, their Cold War supporters—the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union on one side, the United States and its UN allies on the other—had concluded it was not in their respective interests to continue. The chief negotiator for the UN was American Vice Adm. C. Turner Joy; his counterpart was Lt. Gen. Nam Il, the chief of staff of the North Korean People’s Army. At the first session it was agreed that military operations could continue until an armistice agreement was actually signed. The front lines remained relatively quiet, though, as the opposing sides adopted a cautious watch-and-wait stance.

Lt. Gen. James A. Van Fleet’s Eighth Army had fortified its positions along Line Kansas and along Line Wyoming, a bulge north of Kansas in the west-central area known as the Iron Triangle. Both the Kansas line in the east and the Wyoming bulge were above the 38th Parallel, the prewar boundary between the two Koreas. On the west, the front line dipped below the 38th Parallel north of Seoul, the South Korean capital, and then continued to fall toward the coast. This uneven line led to the first impasse in negotiations, when the North Korean and Chinese side argued that the armistice line should be the 38th Parallel, while the UN negotiators called for a line reflecting current positions, which they argued were more defensible and secure than the old border.

When the Communist side broke off negotiations on 23 August, General Matthew B. Ridgway’s United Nations Command (UNC) responded with a limited new offensive. General Van Fleet sent the U.S. X Corps and the Republic of Korea (ROK) I Corps to gain terrain objectives in east-central Korea five to seven miles north of Kansas—among them places that resonate with veterans, such as the Punchbowl, Bloody Ridge, and Heartbreak Ridge. In the west, five UN divisions (the ROK 1st, the 1st British Commonwealth, and the U.S. 1st Cavalry and 3d and 25th Infantry) struck northwest along a forty-mile front to secure a new position beyond the Wyoming line to protect the vital Seoul-Ch’orwon railway. The U.S. IX Corps followed by driving even farther north to the edge of Kumsong.

By the last week of October the UN’s objectives had been secured, and on the 25th the armistice talks resumed—now at P’anmunjom, a hamlet six miles east of Kaesong. When the North Koreans and Chinese dropped their demand that the armistice line be the 38th Parallel, the two sides agreed on 27 November that the armistice demarcation line would be the existing line of contact, provided that an armistice agreement was reached in thirty days. A lull now settled over the battlefield, as fighting tapered off to patrols, small raids, and small unit (but often bitterly fought) struggles for outpost positions. When the thirty-day deadline came and went, as negotiations stalled over the exchange of prisoners of war, among other issues, both sides tacitly extended their acceptance of the armistice line agreement. The continuing absence of large-scale combat allowed the UNC to make several battlefield adjustments, withdrawing the U.S. 1st Cavalry and 24th Infantry Divisions from Korea between December 1951 and February 1952 and replacing them with the 40th and 45th Infantry Divisions, the first National Guard divisions to serve in the war. General Van Fleet also shifted UN units along the front in the spring of 1952, giving more defensive responsibility to the ROK Army in order to concentrate greater U.S. strength in the west.

Meanwhile, the Far East Air Forces intensified a bombing campaign begun in August 1951, supported by U.S. naval fire and carrier-based aircraft. In August 1952 the largest air raid of the war was carried out against P’yongyang, the North Korean capital. Both sides exchanged heavy artillery fire through 1952, and in June the 45th Division, in response to increased Chinese ground action, engaged in an intense period of fighting with the Chinese, successfully establishing eleven new patrol bases along its front. By the beginning of 1953, however, the larger picture was still one of continuing military stalemate, with few changes in the front lines, reflecting the deadlock in the armistice talks that had led the UN delegation to call an indefinite recess in October 1952.

Lt. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor took command of the Eighth Army on 11 February 1953. By March he was faced with renewed enemy attacks against his frontline outposts. Despite the fact that the armistice talks had resumed on 26 April, accompanied by a major exchange of sick and wounded UN and enemy prisoners, flare-ups occurred again in late May and on 10 June, when three Chinese divisions attacked the ROK II Corps defending the UN forward position just south of Kumsong. By 18 June the terms of a final armistice agreement were almost settled, but when South Korean President Syngman Rhee unilaterally allowed some 27,000 North Korean prisoners who had expressed a desire to stay in the South to "escape," the final settlement was further delayed. The Chinese seized on this delay to begin a new offensive to try to improve their final front line. On 6 July they launched an attack on Pork Chop Hill, a 7th Division outpost, and on the 13th they again attacked the ROK II Corps south of Kumsong (as well as the right flank of the IX Corps), forcing the UN forces to withdraw about eight miles, to below the Kumsong River. By 20 July, however, the Eighth Army had retaken the high ground along the river, where it established a new defensive line.

As the UN counterattack was ending, the P’anmunjom negotiators reached an overall agreement on 19 July. After settling remaining details, they signed the armistice agreement at 10 o’clock on the morning of 27 July. All fighting stopped twelve hours later. The cease-fire demarcation line approximated the final front. It ranged from forty miles above the 38th Parallel on the east coast to twenty miles below the parallel on the west coast. It was slightly more favorable to North Korea than the tentative armistice line of November 1951, but compared to the prewar boundary, it amounted to a North Korean net loss of some 1,500 square miles. Within three days of signing both sides were required to withdraw two kilometers from the cease-fire line. The resulting demilitarized zone has been an uneasy reality in international relations ever since.

Posters Available as PDF Files:

|

Phase 1, 27 June-15 September 1950 Phase 2, 16 September-2 November

1950 Phase 3, 3 November

1950-24 January 1951 Phase 4, 25 January-21 April 1951

|

|

| Phase 5, 9 July 1951-27 July 1953 (UN Summer-Fall Offensive 1951) (Second Korean Winter) (Korea, Summer- Fall 1952) (Third Korean Winter) (Korea, Summer 1953) |

Available for Download in

July 2001 |

Instructions for ordering these posters and other CMH products

page created 31 January 2001