-

- With its reduced staff G-1 consisted of the Officers, Enlisted, and

Miscellaneous Branches. A Statistics Branch was added in July 1943 to

help develop uniform personnel reporting in the Army. A new

Legislative Section merged with the Miscellaneous Branch to form a

Legislative and Special Projects Branch. In March 1944 the Office of

the Director of the Women's Army Corps was assigned to G-1.

-

- A major reorganization in April 1945 set up a Personnel Group (later

called the Policy Group). A Planning Branch was added to it later to

deal with personnel readjustment policies and universal military

training. Finally in August 1945 a Control Group was set up to include

the Statistics Branch, plus a Requirements and Resources Branch and an

Allocations Branch responsible for the replacement system generally.

Both branches were transferred from G-3. G-1's remaining functions

were consolidated into a Special Group, including a Miscellaneous

Branch now responsible for personnel and morale services previously

performed by The Adjutant General's Office and the Special Services

Division of Army Service Forces.7

- [106]

- A major factor complicating G-1's burden of co-ordinating and

supervising Army-wide personnel operations was the division of

responsibility for personnel functions among a great many different

agencies at all levels of the War Department from the Secretary of

War's Office on down the chain of command.8

-

-

- Too large rather than too small a staff created serious management

and organization problems for G-2. Its staff more than doubled in size

from 1,000 in 1941 to 2,500 at the end of the war.9

In order to

separate G-2's staff from its operating functions, the Marshall

reorganization had created a new field agency, the Military

Intelligence Service (MIS), theoretically outside the department, as

an operating command. Almost immediately the distinction between G-2

and the MIS was largely wiped out by appointment of the Deputy

Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, as the Chief of the Military

Intelligence Service and the G-2 Executive Officer as Assistant Chief

of the Military Intelligence Service for Administration.

-

- Initially the MIS was divided into four groups, each under an

assistant chief: Administrative, Intelligence, Counterintelligence,

and Operations. A Foreign Liaison Branch and a Military Attache

Section reported separately to the Chief of the Military Intelligence

Service.10

-

- Maj. Gen. George V. Strong became the G-2 in May 1942. He, like most

other Army officers, thought the whole concept of separating staff and

operating functions impractical and recommended the abolition of the

Military Intelligence Service as a separate agency. In the two years

that he was its chief, G-2 and the MIS underwent four major

reorganizations resulting finally in the abolition of the MIS. The

principal issue was the function of evaluating intelligence and

whether this should be performed by G-2 as a staff function or by the

MIS. This version

- [107]

-

of the staff

versus operations controversy would remain a major

issue within the American intelligence community.11

-

- Secretary Stimson, General Marshall, and General McNarney became

progressively dissatisfied with the management and organization of the

Army's intelligence operations. This dissatisfaction came to a head

after General Strong's departure as chief in February 1944. A special

War Department board under Assistant Secretary McCloy, assisted by a

working group under Brig. Gen. Elliot D. Cooke from the Inspector

General's Office, met to study means of strengthening Army

intelligence. The resultant reorganization once again separated G-2

and the Military Intelligence Service, although the latter retained

the function of evaluating intelligence. At the same time the MTS was

relieved of all other functions except the collection, evaluation, and

dissemination of information. Counterintelligence, training, and

propaganda operations were removed from MIS and continued under the

General Staff supervision of G-2 along with a World War II Historical

Section, which had been established in August 1943. The Military

Intelligence Service itself was reorganized along functional lines

with a Directorate of Information responsible for the collection and

dissemination of intelligence, a Directorate of Intelligence

responsible for evaluation, and a Directorate of Administration. Co-ordinating

and directing the MIS and other intelligence operations within G-2 was

a policy staff similarly organized along functional lines.12

-

- These changes, according to General McNarney, created much

bitterness and resentment within G-2 and the MIS, but

"frankly," he told the Patch Board, "G-2 defeated me. I

never got G-2 organized so that I thought it was functioning

efficiently." The principal reason, he thought, was the innate

conservatism of professional intelligence personnel and their

resistance to new ideas. "What I would like to do," he said,

"is get rid of anybody who has ever been military attache and

start new from the ground up."13

-

[108]

-

- Of all the General Staff divisions G-3 was least affected by the

Marshall reorganization. In contrast to the others its organization

remained rather stable throughout the war. There were an Organization

and Mobilization Group and a Training Branch, both divided along

ground, air, and service forces lines. A Policy Branch was added at

the end of the war. At this time also responsibility for the Army's

replacement system was transferred to G-1 from G-3.14

-

- G-3 officers like their colleagues found that it was impractical to

try to draw a strict line between planning and operating functions.

For example, as a policy planning agency G-3 made monthly allocations

of training ammunition to AGF troops. In the process it also had to

determine the necessity, suitability, and utilization of training

facilities before their procurement, all of which were operating

functions.15

-

- The fragmentation of responsibility for personnel, aggravated by the

manpower shortage, was the principal frustration for G-3 during the

war. It was responsible for mobilizing, demobilizing, and training the

Army, for determining the overall size or troop basis of the Army, for

establishing unit tables of organization and equipment, and for

dealing with OPD on allocating troops for overseas shipment. All of

these functions depended upon the availability of military manpower.

-

- Until the end of the war when these functions were transferred to

G-1, G-3 was responsible for maintaining statistics on the

availability of troops and units for deployment overseas and for bulk

allocation of military personnel to the three major commands. G-3

correlated statistics reported periodically by Army Ground Forces,

Army Air Forces, and Army Service Forces. Using these statistics as a

base OPD would then determine what units or troops were to be sent

overseas in response to forecasts or requests from theater commanders.

Since the basic statistics were prepared by the major commands and the

decisions on deployment of troops overseas were made by OPD, G-3 in

practice was little more than an intermediate co-ordinating staff

layer. Its difculties were increased by the

- [109]

- manpower shortage and the apparent irreconcilability of statistics

from various sources on the number of men actually in the Army at any

given time.

-

- Other problems aggravated the manpower shortage, particularly the

distribution of troops between combat and support elements. General

Somervell and his staff were firmly convinced that throughout the war

overseas commanders, OPD, and AGF continually underestimated the need

for service troops overseas. This problem was particularly acute in

the year following Pearl Harbor and frequently required General

Somervell's personal attention and intervention at the highest levels

of command.16

-

-

- While division of responsibility created serious problems for G-1,

the reverse was true in the case of G-4. Its major problem was the

deliberate centralization of responsibility for supply and supply

planning in General Somervell and ASF by General Marshall. For most of

the war his staff rather than the G-4 staff dealt with OPD and the

various joint and combined committees on logistical planning. When

General Somervell attempted to obtain formal recognition of his status

as General Marshall's supply adviser instead of G-4 in mid-1943, his

proposal backfired. As a result G-4's formal functions and its staff

were increased.17

The assignment to G-4 of officers unfamiliar

with the Army's supply system created additional problems.

-

- Under the Marshall reorganization, G-4 at first consisted of the

Planning, Supply, and New Weapons and Equipment Branches. After a

reorganization in October 1943, the investigation of overseas supply

problems by a board under Maj. Gen. Frank R. McCoy, and further

reorganizations in July and October 1944, G-4 consisted of three

branches, Planning, Policy, and Programs. Theoretically the Planning

Branch prepared long-range plans. Looking forward as far as the next

war the Programs Branch was to translate long-range plans into

-

[110]

- supply programs covering the next year or two, while the Policy

Branch made "policy" decisions on current matters. As a

practical matter it was still the ASF Planning Division under General

Lutes that performed the detailed logistical planning for current and

projected overseas operations in conjunction with strategic plans

developed by OPD.

-

- The Planning Branch had a Theater Section which supposedly developed

broad policies and directives for the use of the Army's logistical

forces both overseas and in the zone of interior. It had special

responsibilities for hospitalization and evacuation. Another mission

was to develop a uniform, coordinated set of supply regulations out of

the welter of conflicting directives on the subject issued by various

agencies at all levels of command.

-

- An Organization Section studied, reviewed, and revised the Army's

logistical organizations. A Special Projects Section studied

logistical doctrine, supervised management of Army logistics, and was

responsible for logistical aspects of mobilization, demobilization,

and postwar planning.

-

- The Programs Branch was responsible for balancing military

requirements with the resources available and for approving new

equipment and materiel. Its Equipment Section dealt with new weapons

and equipment. A Requirements Section developed the Army's supply

requirements. After July 1944, it also prepared the supply section of

the Army's Victory Program Troop Basis and the Overseas Troop Basis

and coordinated the Army Supply Program generally. All three functions

had been previously performed by OPD. An Allowances Section analyzed

and approved standard as well as special allowances of equipment for

Army combat units and other organizations. An Installations

Section determined supply plans and policies as they applied

specifically to posts, camps, stations, and other facilities under the

Army Installations Program.

-

- The Policy Branch was responsible for solving problems arising out

of current supply operations. A Distribution Section handled issues

affecting the distribution, storage, issue, and maintenance of

equipment. A Property Section handled questions concerning the

acquisition of land, construction of facilities and installations, and

similar housekeeping functions. An Economics Section dealt with issues

involving Allied supply

- [111]

- programs under lend-lease and supply requirements for liberated and

occupied territory. As such, it was the point of contact within G-4

for the new Civil Affairs Division.18

-

-

- Of the five new War Department Special Staff divisions added after

the Marshall reorganization, two of them, the War Department Manpower

Board and the Strength Accounting and Reporting Office, concerned

personnel; another, the New Developments Division concerned research

and development of new weapons and material; a fourth, the Civil

Affairs Division, dealt with military government of liberated and

occupied territories; a fifth, the Special Planning Division, was

responsible for demobilization planning, universal military training,

and the postwar organization of the Army. Three former special staff

agencies assigned by the Marshall reorganization to Army Service

Forces, the Budget Division, the National Guard Bureau, and the Office

of the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs, were restored by the

end of the war as special staff divisions as-the result of political

pressure from Congress. The Information and Education Division, an

outgrowth originally of The Adjutant General's Office's

responsibilities for personnel and morale services, became a special

staff agency in September 1945, when the War Department decided to

merge all information services under a Director of Information who

reported to the Chief of Staff. The other agencies involved, the

Bureau of Public Relations and the Legislative and Liaison Division,

were already special staff agencies.

-

-

- The political consequences of American military operations in

liberated and later occupied enemy territory were such that neither

Secretary Stimson nor General Marshall could avoid assuming personal

responsibility for them. Secretary Stimson centralized War Department

responsibility for this function in the Civil Affairs Division created

on 1 March 1943 as a special staff division of the War Department

General Staff.

- [112]

- GENERAL EISENHOWER. (Photograph taken in 1945.)

-

- Military government policy had become a critical problem shortly

after the landings in North Africa at the end of 1942 when Lt. Gen.

Dwight D. Eisenhower found himself in political difficulties because

of his dealings with Admiral Jean F. L. Darlan as de facto head

of the local French administration. Eisenhower requested instructions

from the War Departmenton how to deal with the situation.

-

- At that time, following the precedent of World War I, military

government was the responsibility of the local overseas theater

commander. There was no single agency within the War Department to

provide direction on this subject. By default OPD, as the liaison

between General Eisenhower and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was handed

the problem.

-

- In March 1942 a military government training school at the

University of Virginia in Charlottesville was established under the

Provost Marshal General. Efforts to develop military government policy

bogged down in disagreement within the administration over whether

control over civilian populations in militarily occupied areas should

be a military or civilian function. Similarly, efforts to agree on a

War Department position on military government were stymied by

disagreement within the General Staff until General Eisenhower's

request made the problem immediate and urgent.

- [113]

- Secretary Stimson sent Assistant Secretary McCloy overseas to North

Africa to investigate and report on the problem. The creation of the

Civil Affairs Division (CAD) was the result of recommendations Mr.

McCloy made on his return. Now a single staff division was responsible

for advising the Secretary and the Chief of Staff on nonmilitary

matters "in areas occupied as the result of military

operations." Its staff was small, and it had no operating

functions. The Provost Marshal General continued to run the Military

Government School, and theater commanders carried out policies and

instructions issued through the Civil Affairs Division.19

-

- Having created the Civil Affairs Division, Secretary Stimson had

also to decide whether the chief should be a military man or a

civilian in uniform. Choosing the former, he selected Maj . Gen. John

H. Hilldring, an experienced General Staff officer and former G-1, who

remained chief of the division throughout the war. The division staff

was organized along functional lines based on essential community

services, and each functional branch was divided along geographic

lines.20

-

- CAD dealt with theater commanders overseas through OPD which had one

representative on the staff of CAD. The International Division of ASF,

concerned with civilian supply problems overseas, also had a

representative in CAD.

-

- The State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee was formed in December

1944 to co-ordinate foreign and military policies. CAD had a

representative on this committee and on the Working Security Committee

set up in Washington to assist the European Advisory Commission,

working under General Eisenhower in London; on the development of

postwar policy toward Germany. Finally CAD had to deal with the United

Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). Under

- [114]

- former Governor Herbert H. Lehman of New York UNRRA had an obvious

direct interest in civilian relief supplies.21

-

-

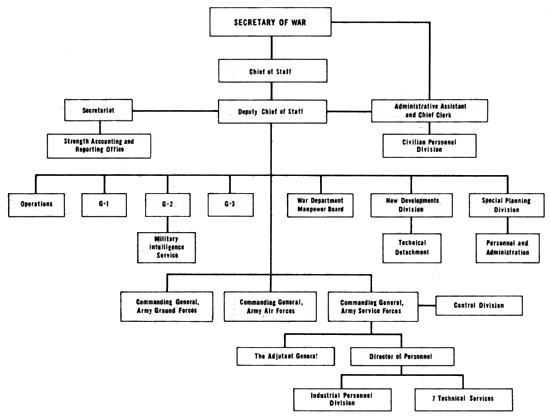

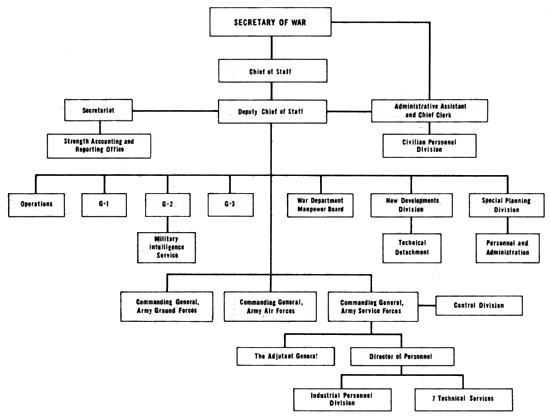

- Because no critical manpower shortages developed during World War I,

the War Department did not anticipate the problem in World War II. A

second complicating factor was the division of responsibility for

personnel policy and operations among many agencies within the

department. (Chart 9) Centralizing responsibility for this

.function in one agency would have required a major reorganization

causing dislocation and administrative turmoil throughout the Army.

-

- Responsibility for military personnel operations was divided among

G-1, G-3, OPD, the three major commands, the seven technical services,

and the administrative services. Responsibility for civilian personnel

was divided among the Secretary of War's Civilian Personnel Office,

Army Service Forces, and the technical services.

-

- After the Marshall reorganization, G-1 was supposedly limited to

policy planning and co-ordination among the three major commands. But,

in practice, as indicated earlier, with its drastically reduced staff

it became a co-ordinating agency more concerned with administration

than planning.

-

- Army Ground Forces resisted the authority of ASF over military

personnel operations, and the Air Forces were busy developing their

own separate system of personnel administration. Within ASF both the

Personnel Division and The Adjutant General's Office were responsible

for Army-wide military personnel operations, including personnel and

morale services. The Adjutant General was responsible for the

induction, classification, and assignment of military personnel. G-3

prescribed the size and composition of units in the Army through

tables of organization, and it allocated military personnel in bulk to

the major commands. OPD regulated the flow of units and replace-

- [115]

- FRAGMENTATION OF WAR DEPARTMENT PERSONNEL FUNCTIONS, 1944-1945

-

-

- Source: Nelson, National Security and the General Staff; Darr

Memorandum; G-1 History; G-2 History; Strength Accounting Special

Planning Division History; Green, Thompson, and Roots, Planning

Munitions for War; and Millett, Army Service Forces.

- [116]

- ments overseas. The technical and administrative services had their

own traditional personnel management systems.

-

- The Civilian Personnel Division in the Secretary of War's Office was

responsible initially for all War Department civilian personnel

operations, while ASF's Industrial Personnel Division took over

responsibility for civilian personnel management among technical

service installations in the field including labor relations. The

Civilian Personnel Division continued to be responsible for civilian

personnel management within the War Department itself. The latter's

actions frequently conflicted with similar activities in the

headquarters of the technical services and, of course, AAF

headquarters.22

-

- Lacking centralized responsibility for personnel policy and

operations, the only practical alternative for the War Department when

the manpower shortage did develop in late 1942 was to create another

special agency-the War Department Manpower Board-for dealing with this

aspect of the problem. Divided responsibility led to conflict among

the various agencies of the Army over just how many men there were in

the Army. Another special agency, the Strength Accounting and

Reporting Office, was established within the Chief of Staff's Office

to co-ordinate and standardize personnel statistics within the Army.

-

- Government leaders, including General Marshall, gradually became

aware by the end of 1942 that there was not enough manpower available

in the country to meet all the nation's requirements, both civilian

and military. The Bureau of the Budget inaugurated a program to

conserve manpower within the federal government and was responsible

for setting civilian manpower ceilings for each agency. In March 1943

General Marshall, on the recommendation of an emergency committee of

the General Staff and the three commands, created the War Department

Manpower Board under another former G-1, Maj. Gen. Lorenzo D. Gasser.

The board reported directly to the Chief of Staff, recommending

specific manpower savings, both civilian and military, on the basis of

detailed surveys of War

- [117]

- Department activities and installations within the continental

United States. Most of the surveys were conducted by teams located in

each of the nine service commands and the Military District of

Washington. The activities surveyed were under ASF's jurisdiction. Its

Control Division assisted teams, using industrial work measurement,

work simplification, and standardization techniques which produced

considerable savings in manpower. The Industrial Personnel Division

conducted similar surveys. As a result of these combined efforts, the

War Department Manpower Board claimed at the end of the war that it

had reduced the number of civilian and military employees of the War

Department and the Army within the United States by about one-sixth of

its wartime peak in June 1943. It said further savings could be

obtained if unnecessary duplication of functions among the technical

and administrative services were eliminated, particularly in their

headquarters.23

-

- Conserving military manpower was harder than conserving civilian

manpower. The main problem that developed in this area was to provide

an effective replacement system that would meet the needs of overseas

commanders. The latters' advance estimates of how many people they

would require were generally inaccurate, but the greatest difficulty

was the inability of the Army to account accurately for troops

"in the pipeline," moving from one organization, station, or

area to another, in hospitals, on leave, on detached service, or at

school.

-

- Divided responsibility for personnel administration inevitably led

to conflicting reports on the number of men actually in the Army which

the department could not reconcile. Public ventilation of these

discrepancies caused Secretary Stimson and General Marshall acute

embarrassment, especially in their relations with Congress.

-

- The department first sought to alleviate the problem by requiring

that all public statements on Army strength be cleared through G-1.

General McNarney also appointed an ad hoc committee to investigate the

problem. The result was

- [118]

- the creation in May 1944 of a new special staff agency within the

Office of the Chief of Staff, the Strength Accounting and Reporting

Office, which was to improve and standardize manpower reporting. With

the issuance of its first monthly edition of the Strength Report of

the Army series in July 1944, this office steadily improved and

refined military manpower reporting within the Army. 24

-

- Manpower conservation and improved statistics were not enough.

Divided responsibility for control over personnel management was a

stubborn obstacle that did not yield to piecemeal solutions. The Army

never did succeed in developing a satisfactory replacement system

during the war. Only the end of the war and the shift to

demobilization removed the problem for the time being. Two Air Force

management experts, Drs. Edmund P. Learned and D. T. Smith, appointed

specifically to study the Army personnel replacement system reported:

-

- No single agency in the War Department General Staff has adequate

responsibility or authority to make an integrated Army-wide personnel

system work. There are too many offices . . . in the personnel

business; there is some confusion in responsibility and no one place

that can be held responsible for a total summary of the situation.25

-

- Of their recommendations for centralizing responsibility for the

replacement system, the department acted on only one-to transfer

responsibility for allocating replacements from G-3 to G-1. OPD

continued to allocate combat replacements and so spread the over-all

manpower shortage among the various overseas theaters.26

-

- Had the Army and the department been able to resolve all internal

personnel problems and conflicts a nationwide man-

- [119]

- power shortage would still have been beyond their power to solve.

Both Secretary Stimson and General Marshall were frustrated in trying

to deal with this problem because neither the President nor Congress

was willing to vest in one agency sufficient authority to determine

manpower allocations among all the claimants. The Secretary and

General Marshall repeatedly urged enactment of compulsory national

service legislation similar to the system adopted by the British. This

would have meant the conscription of industrial and agricultural

labor. Strong opposition by labor unions and farm organizations to

this proposal led to its rejection in Congress and within the

administration.27

-

-

- Research and development of new weapons and equipment in the Army

suffered from subordination to production throughout the war. Agencies

responsible for research and development, whether at the General

Staff, ASF, or technical services, were subordinate elements within

organizations primarily concerned with production and supply.

-

- Dr. Vannevar Bush, president of the Carnegie Institution of

Washington, Director of the Office of Scientific Research and

Development, chairman of the joint Committee on New Weapons and

Equipment of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and chairman of the Military

Policy Committee of the Manhattan District, told the House Committee

on Military Affairs that the armed services did not sufficiently

realize the importance of science because military personnel by

training and tradition did not appreciate the contribution it could

make to national defense. They had not learned as industry had

"that it is fatal to place any research organization under

production departments. In the services it is still the procurement

divisions who maintain the research organizations."

-

- Basically, research and procurement are incompatible. New

developments are upsetting to procurement standards and procurement

schedules. A procurement group is under the constant urge to

regularize and standardize, particularly when funds are limited. Its

primary function is

- [120]

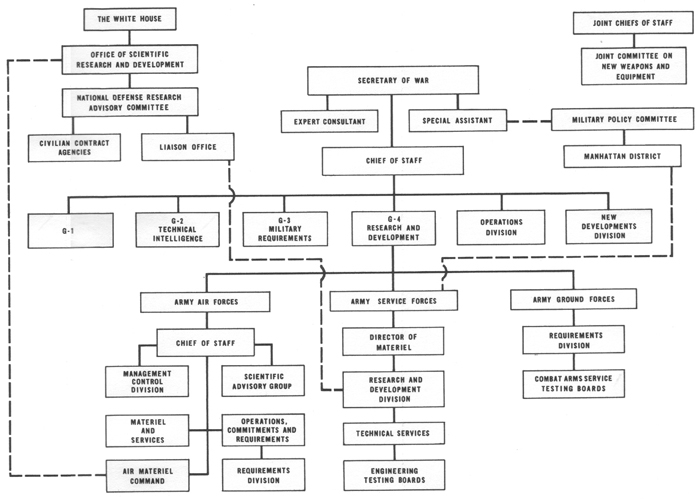

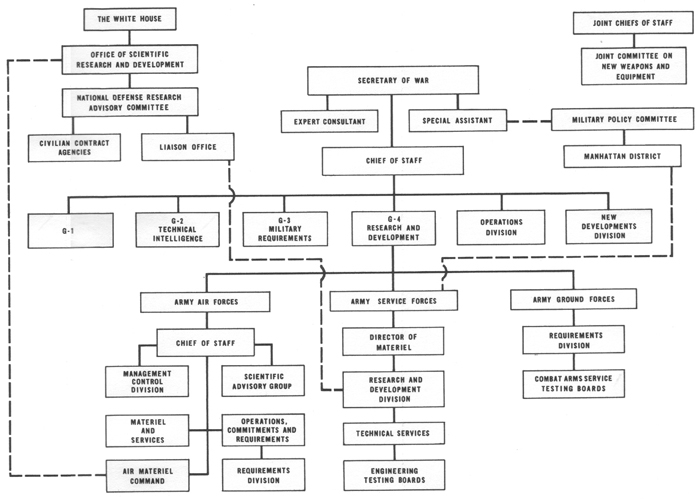

- RESPONSIBILITY FOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT OF NEW WEAPONS AND

MATÉRIEL WITHIN THE WAR DEPARTMENT, SEPTEMBER 1945

-

-

- Source: Nelson, National Security and the General Staff, New

Developments Division History; McCaskey, The Role of the Army Ground

Forces in the Development of Equipment; History of Research and

Development Division, ASF; Green Thomson and Roots, Planning Munitions

for War; Millett, Army Service Forces; Stewart, Organizing Scientific

Research for War; Morison, Turmoil and Tradition; and Hewlett and

Anderson, The New World.

-

- to produce a sufficient supply of standard weapons for field use.

Procurement units are judged, therefore, by production standards.

-

- Research, however, is the exploration of the unknown. It is

speculative, uncertain. It cannot be standardized. It succeeds,

moreover, in virtually direct proportion to its freedom from

performance controls, production pressures and traditional approaches.28

-

- Functionally, the issue was again one of planning versus operations

where mixing planning with operational responsibilities led to the

neglect of planning. A second and more immediately important obstacle

was the division of responsibility for the research, design,

development, production, testing, procurement, and battlefield

deployment of new weapons and equipment among many agencies. (Chart

10) The most serious division and the one which caused the most delay

was that between the technical services as producers and the AGF and

combat arms as users.

-

- Within the Army the technical services throughout the war were the

agencies responsible for nearly all military research and development

except for the AAF, which had its own programs. G-4 exercised General

Staff supervision over the technical services activities through a

Research and Development Section created in 1940. The combat arms were

responsible for establishing military requirements and characteristics

of new weapons and equipment, for service testing them under simulated

combat conditions, and finally for accepting or rejecting them as

standard Army equipment. Military requirements for new equipment in

turn depended on the development of tactical doctrine. These two

functions were under the General Staff supervision of G-8.

-

- Under the Marshall reorganization, Army Service Forces took over

responsibility for research and development operations from G-4, which

continued to have a Developments Section within its Requirements and

Distribution Branch. Throughout the war this function was buried

within ASF under the Directorate of Materiel and did not even achieve

the status of a separate division until the war's end. This

reflected

- [121]

- the fact that the Materiel Directorate's primary interest in this

area was in the requirements and specifications of those weapons and

equipment already developed and proposed for adoption as standard

equipment by the Army. Since technical services were the agencies

mainly responsible for the conduct of the Army's research and

development efforts, ASF's Research and Development Division was

largely a co-ordinating staff between them and AGE There were lengthy

delays caused by disagreement between the latter, representing the

users, and ASF's research and development staff, representing the

producers, over specifications which had to be negotiated. Another

mission was to promote the use of common items of supplies, and there

were lengthy delays in trying to get the technical services,

particularly the Ordnance Department, to change their specifications.

The Research and Development Division also assisted the technical

services when they had trouble obtaining raw materials, equipment, and

facilities for their research and development programs.

-

- AGF took over operational responsibility in March 1942 for

establishing military requirements for weapons and equipment and for

the development of tactical doctrine from G-3 and the former combat

arms, assigning these functions to its own G-3 and Requirements

Division.29

-

- Conflicts between the technical services and AGF delayed production

and procurement of new materiel. Often differences between them could

not be resolved short of General Marshall himself. A classic example

was the dispute between the AGF in the person of General McNair and

the Ordnance Department over the development of a heavy tank. Armored

doctrine held that there was no need for a heavy tank because it moved

too slowly. Mobility was the vital characteristic, and both armor and

firepower should be subordinated to it. One result was the development

of a light, half-track armored vehicle known as a tank destroyer which

proved unable to cope with heavier German tanks in North Africa.

(Later tank destroyers,

-

[122]

- like tanks themselves, were full-tracked.) Another was the repeated

veto by General McNair of heavy tanks proposed by the Ordnance

Department. Such a tank finally saw action at the end of the European

war, having been held up for over two years.30

-

- There was a tendency among combat officers, the Air Forces excepted,

to ignore radically new departures in development of new equipment in

favor of tinkering with or improving existing weapons. This

conservative tendency stemmed in part from their general unfamiliarity

with scientific and technological developments or with production and

engineering. Second, the better tended to be the enemy of the good.

Developers charged that representatives of the combat arms repeatedly

rejected equipment that was not perfect. This often involved

redesigning and further delay simply to incorporate some new

feature.31

-

- Secretary Stimson was dissatisfied with the slowness of research in

the Army, particularly in the field of electronics. His special

assistant, Mr. Harvey H. Bundy, was a troubleshooter on scientific

problems and acted as liaison with the scientific community. His

special task was to oversee the development of the atomic bomb. In the

spring of 1942, Mr. Stimson appointed Dr. Edward L. Bowles of MIT as

his Expert Consultant to push the development of radar in particular

and other improvements in the field of electronics. He had a staff of

forty-seven specialists who made frequent trips overseas to obtain

firsthand evidence of combat requirements.32

-

- Mr. Stimson also became a close friend of Dr. Bush who urged greater

emphasis on scientific research in developing new military equipment.

An engineer by profession, Dr. Bush

-

[123]

- was by virtue of the many key positions he held during the war

probably the most influential and the most articulate representative

of the scientific community in the defense program. He and Dr. Bowles,

acting through Stimson, were responsible for increasing the Army's

participation in the development of new weapons and other materiel.

They were dissatisfied with the Army's research and development

programs. Partly because of their slowness to act in this area, the

Chief of Ordnance in 1942 and in 1943 the Chief Signal Officer were

replaced. The influence of the Office of Scientific Research and

Development (OSRD) and Dr. Bowles on AAF research and development and

on the use of operations research techniques has been mentioned

previously. The Ground Forces never did make any significant use of

the latter during the war.33

-

- Pressure on the department also came from the battlefields. Reports

from the Pacific on the unsuitability of existing equipment for jungle

or amphibious combat led General Marshall to send a team of experts to

that area under Col. William A. Borden to investigate and report

directly to him on the kinds of weapons and equipment needed in the

area. Colonel Borden, an Ordnance expert with a flair for salesmanship

and diplomacy, was then General Somervell's Special Assistant to the

Director of Plans and Operations, a cover for his primary function as

a troubleshooter.

-

- In October 1943, acting on the recommendations of Bundy, Bush, and

Bowles, Stimson created the New Developments Division as a special

staff division to expedite production and procurement of new and

improved equipment. Under Maj. Gen. Stephen G. Henry the New

Developments Division was primarily a troubleshooting agency with a

limited staff of about two dozen civilian and military personnel. They

tried to bridge the gap between producer and consumer and to hasten

delivery of equipment to the battlefield.34

-

- The division's members accompanied scientists and technicians of

OSRD's field service overseas to test and evaluate new materiel. The

principal problem as well as that of the Research and Development

Division of ASF was the delay

- [124]

- caused by disagreements between the technical services and the

combat arms over testing equipment. While the Research and Development

Division was flooded with the paper work created by this problem, the

staff of the New Developments Division spent more of its time in the

field trying to find short cuts around the rigid testing requirements

of AGF. This was handled on a case-by-case basis, and with a small

staff its success was limited. The problem remained unsolved at the

end of the war.35

-

- Another duty assigned the division as the result of the manpower

shortage was to provide a pool of technical and scientific specialists

drafted into the Army. Induction centers, pressed for combat

replacements, generally assigned these individuals to the combat arms.

An Army Technical Detachment added to the New Developments Division in

October 1944 tried to locate such personnel before they became

assigned as combat replacements. In its year of operation the

detachment had located and assigned four hundred such specialists to

the technical services and other installations performing research and

development, but it still had a backlog of over eight hundred unfilled

requests.36

-

- The Manhattan Project, organized to supervise the production of the

atomic bomb, pioneered in what later became known as project

management. The Army took over direction of the atomic program in

mid-1942, when scientists working under the Office of Scientific

Research and Development had demonstrated that an atomic weapon was

technically feasible. Producing the fissionable material required to

detonate the bomb involved enormous outlays of men, money, and

resources, including huge amounts of electricity and water. The Corps

of Engineers was selected to construct and operate the required

installations and facilities because of its experience with

large-scale

public works projects.

- [125]

- Secretary Stimson with the approval of President Roosevelt placed

Brig. Gen. Leslie R. Groves, the man responsible for building the

Pentagon, in charge of the project. His organization was known

as the Manhattan District of the Corps of Engineers, but the Chief of

Engineers was relieved of responsibility for the project shortly after

General Groves' appointment. For practical purposes, it was an

independent agency. General Groves reported to a Military Policy

Committee set up to oversee the project and determine general policy.

Dr. Bush was its chairman. On the committee were Maj. Gen. Wilhelm D.

Styer, General Somervell's deputy, Admiral William R. Purnell, and Dr.

James Bryant Conant, president of Harvard and head of the National

Defense Research Advisory Committee of OSRD. Conant and Bush

represented the interests of the scientific community. General Groves

also reported directly to General Marshall and to Secretary Stimson,

usually through Mr. Bundy's office.37

-

-

- As Chief of Staff of the Army during World War II, General Marshall

had two principal missions. He was the Army's chief strategy adviser

and also general manager of the department. The increasing size and

complexity of the Army's operations as the United States gradually

mobilized for war made it physically impossible for Marshall to

perform both functions. Since his major function was to advise

President Roosevelt on strategy and military operations, he was forced

to divorce himself more and more from his administrative functions as

general manager of the department.

-

- From Marshall's viewpoint the existing structure and standard

procedures of the Army's General Staff made it practically impossible

for him to delegate responsibility for administration to the General

Staff. Its committees were too slow in reaching collective decisions

and could not distinguish between important questions and minor

details which they constantly thrust at him for decision.

- [126]

- Passage of the First War Powers Act in December 1941, right after

Pearl Harbor, gave Marshall the opportunity to streamline the

department's organization. Under the new organization he delegated his

administrative responsibilities to a single Deputy Chief of Staff

within the department and to three new major field commands, Army

Ground Forces, Army Air Forces, and Army Service Forces. At the same

time he selected his own principal deputies and subordinates. The

reorganization left him free, as he insisted, to concentrate on

military strategy and operations aided by the staff of the War Plans

Division. Redesignated the Operations Division it became an operating

headquarters instead of a planning agency. In effect it became a super

general staff, bypassing the other General Staff divisions in the

interests of prompt action.

-

- In this manner General Marshall could control departmental

operations by decentralizing responsibility for their administration

just as the pioneer industrial managers at DuPont, General Motors, and

Sears had done in the previous decades. Although Marshall was

apparently not familiar with these earlier industrial management

reforms, it is not surprising that he, faced with similar problems,

came up with similar solutions. Marshall's understanding of the basic

principles of management as well as his exceptional judgment of men

made him one of the department's most effective administrators. The

results of his reorganization were so satisfactory that he strongly

recommended applying the same principles in organizing a new

department of the armed services after the war.

-

- General McNarney, as Deputy Chief of Staff and general manager,

exercised tight control over the department, except for his increase

in the functions and personnel of G-4 in mid1943. General Handy, his

successor who had previously been Chief of the Operations Division,

was more sympathetic to the General Staff, which Marshall and McNarney

had largely ignored. Handy was also more critical of Somervell's ASF

than McNarney.

-

- The difficulties Marshall and McNarney had with the management of

intelligence, personnel functions, and research and development of new

weapons indicated that the reorganization had not solved all problems

of administration. The relations between the functionally organized

ASF headquarters and the

- [127]

- offices of the chiefs of the traditional technical services

presented another difficult problem. Large industrial corporations

which attempted to combine a functionally organized headquarters with

a decentralized product-oriented field structure were experiencing

similar difficulties.38

-

- Supervising and co-ordinating the technical services along

functional lines which cut across formal channels of command

inevitably generated friction. If the offices of the chiefs of the

services had been phased out of existence as had been done with the

chiefs of the combat arms within AGF, there might have been less

friction and ill-feeling. AAF headquarters deliberately created its

own integrated supply system from the start and did not have to deal

with any technical services with long-established traditions and

influence.

-

- ASF might have solved its organizational and management problems by

confining its top staff to broad policy planning and co-ordinating

functions. The technical services chiefs argued for this alternative,

but the experiences of the three major commands led their commanding

generals to insist that their headquarters staff must operate in order

to exercise effective control over their subordinate agencies and

commands.

-

- There were conflicts and jurisdictional disputes between General

Somervell's headquarters and OPD over logistical planning

responsibilities and with AAF headquarters as a result of the latter's

aggressive drive for autonomy.

-

- Although put together in haste, the Marshall reorganization worked

as well as it did because General Marshall was the real center of

military authority within the department. Both Roosevelt and Secretary

Stimson supported him. In turn General Marshall delegated broad

responsibility with commensurate authority to Generals McNarney,

McNair, Arnold, and Somervell. While the Marshall reorganization

lasted only as long as he was Chief of Staff, it was based upon the

accepted military principle of unity of command and similar to

concepts of administrative management developed by major industrial

corporations.

- [128]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents