CHAPTER XIX

The Medical Department (ASF)

Slowest of all ASF services to employ Wacs, the Medical Department by the end of the war had become the greatest user, employing some 20,000 Wacs, one fifth of the entire Corps, almost one half of Army Service Forces WAC personnel. These were to be found in general, regional, and station hospitals, ports, air bases, and convalescent centers, as well as in the few installations directly under The Surgeon General's command, such as the Army Medical Center in Washington.

The slow start resulted from the fact that well-trained civilian personnel and enlisted men were plentiful when the WAAC was organized. "It is the opinion of this office," stated The Surgeon General at that time, "that it is not desirable to utilize the WAAC in Army hospitals."1 WAAC Preplanners had not pressed the issue, since requisitions from other agencies were already more than could be filled.2

In 1943, when the Service Forces surveyed the possibilities of expanding the Corps to a million members, The Surgeon General appointed a board of medical officers to reconsider the employment of Waacs. Hospital commanders, queried by the board, requested Waacs to a total of some 10,000 women for the ASF and almost as many for the AAF, to replace from 30 to 50 percent of their enlisted men. Nothing came of the study; Director Hobby informed the board that she was "in accord with the idea that members of the WAAC could be utilized in such a capacity," but the difficulties of recruiting prevented her from supplying the personnel.3

During the summer of the conversion, the WAAC was able to make available to The Surgeon General less than two hundred individuals a month, for technical training at the Army-Navy General Hospital.4 Reports indicated that hospitals in the field were also obtaining certain numbers of women from post headquarters companies, although the women had been neither trained nor equipped for the work.

[339]

In early 1944, the nationwide personnel shortage caused the Medical Department an unprecedented loss: the forced transfer to the Infantry of some 5,000 combat-fit men, trained technicians upon whom hospitals had depended for normal operation. This loss brought about really urgent requisitions for Wacs. "The Medical Department is critically short," The Surgeon General's Office protested. "Efforts to hire civilians in sufficient numbers have as a whole failed . . . . With the withdrawal of enlisted men, there will be an urgent need for at least 50,000 additional Wacs to work in medical installations." The Surgeon General therefore asked an "extensive recruiting program" to recruit Wacs specifically for the Medical Department.5

The request for 50,000 Wacs was impossible of fulfillment, nor could the Medical Department be given first priority on even the actual intake without causing withdrawal of Air Forces, port, and other recruiting teams. Instead, Director Hobby was able to offer the Medical Department merely the privilege of recruiting for hospitals under the station-and-job plan, which was a simple matter of adding them to the existing list of participating installations. In the spring of 1944, the Corps' recruiting and publicity media therefore lent their support to what was called the Female Medical Technicians Campaign.

Female Medical Technicians Campaign

The Medical Department's demands were unusually difficult to meet, in that only highly qualified workers were acceptable.6 Particularly sought were women with college training who could serve as bacteriologists, instructors in lip reading and Braille, pharmacists, optometrists, psychiatric social workers, orthopedic mechanics, and numerous other technicians.

Specifications were set for education, training, and experience which were so exceptionally high that the ordinary recruiting station was deemed unable to evaluate them accurately. The Medical Department therefore followed the WAVES' example and secured the assistance of the Officer Procurement Service, which assisted regular recruiters by filling out a qualification certificate guaranteeing assignment to, and suitability for, a technical job.

For example, a WAC psychiatric social worker (Specification Serial Number 263) was required to have "'at least two years of supervised experience in social case work . . . or a graduate degree in social work," and it was stated that those accepted "will be assigned directly upon completion of basic training and are eligible on the basis of such assignment to attain the grade of staff sergeant, dependent on individual ability and the existence of vacancies." A WAC laboratory technician was required

[340]

to have a B.S. degree or three years' experience, and was similarly promised eligibility for a staff sergeant's rating. Other specialties were comparable. The Surgeon General agreed in return to accept the Officer Procurement Service's recommendation without change and to provide the guaranteed assignment.

In addition, regular recruiters were authorized to accept other women for three months' training as medical and surgical technicians, provided that the women had AGCT scores of 100 or better and had graduated from high school. Thus, only women in the upper half of the intelligence range of the population, and of near-officer caliber, were channeled to the Medical Department.

In spite of the high requirements, the Female Medical Technicians Campaign proved reasonably successful, the Medical Department's glamor obviously being second only to the Air Forces'. Women were recruited so surprisingly fast that the entire Medical Technicians' School reserved for WAC training proved inadequate. Within a few months some 4,000 well-qualified women had been recruited for Army hospitals-a number which, though short of 50,000, proved to be all that was required at the time.

It was quickly demonstrated that Medical Department training courses offered women no unusual difficulties. In early months, Medical Department schools were already carrying a peak load, and housing and sanitary facilities for women were so inadequate as for a time to cause a serious welfare problem. This condition was remedied gradually as male enlisted personnel for training became scarcer, until by the end of the war over half of the students at the enlisted technicians schools were Wacs. No alteration was required in the usual training courses for men, except for omission of training in catheterization, which was considered unsuitable. Women in most cases qualified in two months for specialties that ordinarily required three months' training, and in three months for other specialties normally requiring four. Morale and discipline were generally high.7

Relative Success in Medical Jobs

The actual success of women in various types of hospital work varied with the duties. The most successful women were generally those who performed the more technical duties, especially ones related to patient care and reconditioning. Hospital authorities at first had felt that only male combat returnees should help rehabilitate the wounded, "due to personality changes of combat-wounded patients," which would presumably make them allergic to noncombat soldiers, especially female ones. When the first women began to be assigned to hospital work, authorities discovered, instead, that "the psychological reaction to feminine association has been most beneficial in combating certain prevalent attitudes of overseas returnees." Even untrained Wacs, according to commanders, showed natural ability for the work and obtained satisfaction from it. Authorities concluded that, "due to the personal services rendered and to the enthusiasm and understanding exhibited by

[341]

such personnel, there has been a marked increase in the morale of the patients which is definitely considered to be an important part of the therapeutic regimen." In hospitals that pioneered in using Wacs in such work, complete satisfaction was expressed by all concerned.8

Psychiatric Social Worker and Psychiatric Assistant

Although earlier surveys had pronounced women unsuitable for any sort of psychological work with men, the Medical Department successfully employed more than 300 women as psychiatric social workers and psychiatric assistants. Women performed case work, interviewed patients and wrote case histories, carried out psychiatrists' mental hygiene prescriptions, and maintained necessary files and records on mental patients. 9

Educational and Physical Reconditioning Personnel

More than 150 women with college degrees and teaching experience were enlisted and given one month's training in the educational reconditioning course at the Army's Special Services school. They were then employed to teach various school subjects to patients during convalescent periods in Army hospitals. Women were pronounced by medical authorities to be particularly successful in such teaching, since "men are conditioned to female instructors . . . and there is a psychological advantage to their employment."

The same school's course in physical reconditioning was barred to Wacs as inappropriate. One Wac accidentally attended, graduated, and was successfully assigned; others did the work without such training and were pronounced "capable of fully participating in physical reconditioning, without specific limitations." When Wacs conducted games, recreational athletics, and exercises for male patients, there was noted "a marked increase of patient participation and enthusiasm." 10

Therapy Assistants

Although the Medical Department had no authority to commission the highly trained civilian occupational therapists, as did the Navy, it succeeded in securing several on an enlisted status. In addition, more than two hundred women, experts in some handicraft, were recruited and assigned to convalescent hospitals to lighten the load on civilian occupational therapists by teaching leatherwork, weaving, and other crafts to the mentally or physically handicapped.

To assist commissioned physical therapists, the Medical Department gave a short course which successfully trained some 500 Wacs as physiotherapy aides, for duty in general and convalescent hospitals.11

[342]

Laboratory Technicians

More than 700 women were recruited and assigned as laboratory technicians. Those with a B.S. degree or three years' experience were assigned immediately, while others were acceptable for the Army school if they had graduated from high school in the upper half of the class and had some laboratory experience. Women seemed entirely suitable for such duties, which consisted chiefly of analyzing specimens, making blood counts, preparing reagents, performing basal metabolism tests, and typing blood.

Similarly, some 500 women were recruited for X-ray work-those with experience for immediate assignment, and those with high school education, including physics and photography, for three months' training in Army schools. Technicians not only operated X-ray equipment, but prepared patients for treatment, managed protective measures, and developed film.

Medical Stenographers and Clerks

Recruiters had considerable success in locating recruits with both a knowledge of medical terms and the necessary clerical or stenographic skills. Such women were used in hospital offices to type records, prepare reports, take dictation at conferences, and construct technical charts.

Miscellaneous Technicians

With promises of a master sergeant's rating, recruiters succeeded in enlisting approximately a dozen dental hygienists, able to scale and polish teeth and perform other oral prophylactic work. Larger numbers of women with high school education, and of the proper size and weight to fit into a dental cubicle, were also enlisted for three months' Army training as dental technicians and assistants.

The Officer Procurement Service also secured small numbers of recruits for various other technical duties: some forty pharmacists and pharmacists' aides, a half dozen lip reading technicians, and lesser numbers of Braille teachers, optometrists, hearing aids technicians, and others in rare specialties.

Only one flaw marred the assignment of such specialists during most of 1944. This was a certain lapse in liaison between procurement and employment authorities on the matter of salaries. Thus, the Officer Procurement Service's advertisements in professional journals had headlined the Medical Department's statement that Army specialist pay compared favorably with civilian technician pay, and that promotion to the specified rank for each duty depended upon "the proficiencies of the individual and existing vacancies." It had not been made clear that there were no existing vacancies and would not be for the current war; most hospitals' grade allotments were already exceeded by assigned men and by the daily return of highly rated men from overseas. Women recruited under the Female Medical Technicians Campaign therefore could rarely be promoted at all, and almost never to the specified rank. Hospital commanders naturally refused the requests for discharge of specialists who had enlisted under the wrong impression, and tended to blame the Officer Procurement Service for over-glamorization of opportunities. On the other hand, that agency was able to show that it had merely operated on the written specifications furnished it by The Surgeon General's Office, and was not

[343]

clairvoyant as to the internal conditions in Army hospitals.12

Somewhat more fortunate were those few skilled technicians who were recruited on a commissioned instead of enlisted status.13 Since The Surgeon General lacked Congressional authority to commission females in the Sanitary Corps, a special arrangement was made whereby WAC bacteriologists, serologists, and biochemists were commissioned in the WAC and detailed in the Sanitary Corps. Similarly, a number of WAC officers holding administrative jobs in hospitals were detailed in the Medical Administrative Corps to replace combat-fit male officers.

The Surgeon General had for some time had Congressional approval of commissioning women physiotherapists in the Medical Corps, without reference to the WAC. For a time the training course leading to a commission was open only to civilian women. Finally, at Colonel Hobby's insistence and because of difficulties in recruiting students, qualified enlisted women were offered the same opportunity, and several hundred were commissioned. Eventually the Medical Department's interests in this work were found better safeguarded by WAC recruitment of college graduates for training on an enlisted status and subsequent commissioning, and the greater part of the procurement of commissioned physical therapists was thereafter managed through the WAC.

Medical and Surgical Technicians

Greater in numbers than all of the skilled specialists obtained through the Officer Procurement Service or by commissions were those women obtained direct through recruiting stations-the medical and surgical technicians.14 These were to number from 6,000 to 10,000 by the end of the war. Such women ordinarily had no medical experience, but upon proof of the required education and ACCT score were promised training in the Army's enlisted technicians schools and subsequent assignment as medical or surgical technicians.

The duties of such ward personnel proved in general only slightly less suitable for women than those of the Officer Procurement Service technicians. Medical technicians made beds, gave baths, took temperature, pulse, and respiration; prepared patients for meals, carried trays, and fed patients if necessary; gave enemas and bedpans; filled ice-bags and hot water bottles; kept ward records, prepared dressings, and kept linen closets neat. Surgical technicians performed much the same duties, as well as sterilizing gowns and equipment and giving pre- and postoperative care. In general both were intended to assist nurses by relieving them of simple details of patient care.

Wacs ordinarily proved highly adept at such simple nursing duties, and approached the work with an enthusiasm and a sense of dedication not always found among male technicians. On the other hand, it was an accepted principle from the beginning that women could not replace all or even half of the male tech-

[344]

nicians in any installation, since certain duties required great physical strength and others involved services for male patients that were considered inappropriate for women to perform. The accepted ratio was about 40 percent enlisted women to 60 percent men. Where these ratios were preserved, the jobs of medical and surgical technicians appeared extremely well suited for women.

The WAC medical and surgical technicians nevertheless suffered from a particularly obvious comparison with civilian women employed as paid nurses' aides. Trained by the Red Cross, these were almost identical in qualifications and training with the WAC medical technician, and were intended for similar duties. Civilian nurses' aides had figured in Medical Department history since World War I, and were frequently women with home responsibilities who had accepted the work for patriotic reasons. Nevertheless, it was a rare enlisted woman who did not remark the fact that civilian nurses' aides could quit if not given desirable duties, got three times the Wac's salary for half the hours per week, and in addition had officers' privileges on the post, all of which the Wac herself might have had but for the wiles of an Army recruiter.

Possibly no more unhappy example had yet occurred of the unwisdom of recruiting both military and civilian personnel for identical duties and of using them on the same installation. The final indignity to many enlisted women came when all hospital civilian employees were allowed to wear the Wacs' uniform, the surplus blue cotton dress formerly worn by nurses, thus depriving enlisted women of the only visible glory of military status.

The only hospital job on which women were admittedly unsuccessful was the least skilled: that of hospital orderly, or corpsman. Women had never been recruited for this purpose, but in 1943, when certain low-grade workers accumulated at training centers, the WAC requested the Medical Department to train them as ward orderlies.15 The Medical Department accordingly set up an experimental training course, but within a few months was obliged to abandon it, pronouncing women unsuitable for hospital orderlies because of "the limited tasks to which this type of personnel might be assigned, and the impossibility of using them to replace enlisted men as ward orderlies." 16 These women, unlike enlisted men of the same category, could not successfully work long hours lifting heavy objects, pushing loaded food and linen carts, and scrubbing wards and corridors.

Two more attempts to train Wacs as orderlies, at Mayo and Nichols General Hospitals, likewise failed, and The Surgeon General informed the Director that such personnel required so much supervision that the nurses' load was increased instead of lightened. In any case women orderlies could not replace men on a one-for-one basis because of lesser physical strength. Therefore, the position of orderly was not represented in the Female Medical Technicians Campaign, and the standards set for recruits were far above that appropriate for such personnel.17

[345]

Under the circumstances, the War Department was at first unable to account for a growing trend that began to make employment of WAC orderlies the rule rather than the exception. Widespread reports indicated that in many hospitals ward orderlies were beginning to outnumber technicians among WAC personnel. Hospital commanders, for reasons not at once apparent, showed an increasing tendency to assign Wacs of high intelligence and technical training to duties that were exclusively those of charwomen and kitchen police, even when such women had in their possession written Recruiting Service guarantees of assignment as medical technicians, which by specification included no work heavier than "keeps bedside tables neat."

Repeated investigations shortly made clear that, although the Medical Department had acted on the assumption that technicians were needed, hospitals were if anything overstaffed on personnel for patient care and short chiefly in low-grade positions that civilians would no longer accept. A civilian observer reported, "Cadet Nurses, civilian nurses' aides, civilian nurses, Army nurses, and enlisted men are all above them [Wacs] in the hospital caste system and do all the actual medical care of the patients.18 It was clear-at too late a date-that the Medical Department should instead have asked a campaign to recruit women in the lowest aptitude and educational group and without commitment as to duties.

All reports confirmed the situation. The commanding officer of Gardiner General Hospital told inspectors that he "had no use for Wacs except as ward orderlies whom he might use on cleaning and scrubbing duties."19 At Fort Jackson, South Carolina, the commanding officer published a memo stating, "All [WAC] personnel . . . will be used entirely for cleaning of wards."20 From Halloran General Hospital, a Wac wrote:

If I had only known before I joined what I know now they could have shot me before I would have ever joined. Your people at the recruiting office show a beautiful film that shows the girls at work really doing things for the boys . . . . We scrub walls, floors, make beds, dust, sweep, and such only. . . They should stop this farce of recruiting 'medical technicians'' and ask for `mop commandos.21

Even an indignant civilian worker wrote; "Most of them [Wacs] had medical technician training [but] cleaning is all they do officially." 22 Civilian visitors to hospitals-including Mrs. Robert P. Patterson, wife of the Under Secretary of War-likewise protested to the War Department concerning conditions they saw. Mrs. Patterson commented on the WAC orderlies' makeshift uniforms, bedraggled appearance, over-strenuous duties in kitchens, long hours, and lack of the privileges and training given enlisted men. Military visitors carried the same report. Conditions discovered on one visit by the ASF WAC Officer, Colonel Goodwin, were so alarming that they were personally communicated to The Surgeon General's Office by General Dalton, with the advice that he would follow up on action taken. This he directed to include better attention to the women's appearance, better

[346]

salvage and supply, provision of one day off a week for kitchen police and orderlies,. and an investigation of the chances of upgrading orderlies.23

By the summer of 1944, even before the end of the Female Medical Technicians Campaign, the problem had become one of the Corps' most serious. For the few women who had come into the Medical Department before the campaign, the question was merely one of malassignment to a duty possibly above their strength. For those who had been promised assignment as medical and surgical technicians, the matter was the more urgent one of the Army's good faith. A more unfortunate situation, or one more provocative of resentment on all sides, had never before occurred in the Corps' history. To the hard-pressed hospital commander, charged with maintaining patient care, the insistence upon fulfillment of the written recruiting promises seemed an unwarranted infringement upon his command prerogatives in assigning duties to keep the hospital functioning. For the WAC Recruiting Service, it was pure disaster. No other Army command, however much it deplored the necessity of recruiting promises, had ever deliberately violated them, and the Recruiting Service saw the source of supply of Wacs for the entire Army threatened by the personnel practices of one agency.

By early summer of 1944, with the Female Medical Technicians Campaign still continuing, the number of complaints reaching the Director's Office "'from civilian and Congressional sources" was so great that Deputy Director Rice asked the major commands for an investigation to determine the actual situation:

The few investigations conducted in response to some of these criticisms have substantiated the fact that conditions in these assignments are in many instances contrary to the well-being of women. Realizing the load on the hospitals . . . the Director WAC does not wish to recommend to the War Department that women not be utilized in this capacity, but because of conditions now alleged to exist in both time-length of daily scheduled duties (without commensurate time off) and in actual scrubbing work and other menial tasks, she feels that her responsibility for the well-being of women calls for study of such utilization. 24

A simultaneous move came from The Inspector General, who informed the Chief of Staff, ASF, that "possibly there is misassignment of WAC personnel," and asked a survey.25

Reports of surveys, when received some months later, disclosed that the situation was in some respects worse than expected. In the Army Service Forces alone, over 1,200 enlisted women-about 5 percent of its total WAC strength-were found assigned as orderlies. Almost every station or general hospital was guilty in an appreciable number of cases. At one, ten technicians were used as orderlies, at another seven, at another six-in every case a percentage of the company large enough to cause comment. It was found that nonmedical specialists were also being mal-

[347]

assigned as orderlies, one station alone having converted thirty graduates of the motor transport school to this use.26

Surveys also confirmed another fact which began to suggest that hospital work on an enlisted status was possibly not proper for women. This was the difference in hours of work for military and for civilian personnel. The customary hours in Army hospitals were 40 hours a week for civilian employees or 48 hours with overtime pay, and 8 hours a day for Army nurses. Enlisted men were believed to have more endurance, and traditionally worked a 12-hour day in Army hospitals.

The difficulty for Wacs was that they were both female and enlisted. As females, a 12-hour day was no more appropriate for Wacs than for nurses, and even less appropriate when Wacs were used for strenuous physical labor. As one female medical officer observed, "Wacs are replacing enlisted men but you are not turning women into men by an Act of Congress .... Wacs are enlisted women but they are still women." 27 On the other hand, Wacs were enlisted personnel, and if they worked only an 8-hour day the damage to the morale of enlisted men on the same wards was reported to be considerable because of the discrimination involved, and one-for-one replacement was made even more difficult.

The surveys revealed that enlisted women were almost without exception required by hospital commanders to work 12 hours a day and often more. Also, many were working 7 days a week and were not allowed compensatory time off during the work day or any leaves or passes. In addition to the regular 12-hour day, all were obliged to take night calls in emergencies, since civilian nurses' aides were not quartered on the post. Wacs also had to manage on their own time the four-hour weekly continuation training courses required by the ASF, and other duties such as company fatigue, inspections, personal grooming, and sometimes laundry. As a result, enlisted women in Army hospitals were found to be working a minimum of 72 hours weekly and a maximum of at least 100, in addition to company duties. For example, Camp Wheeler, Georgia, employed trained WAC medical technicians as ward orderlies on a 12-hour, 7-day week, a total of 84 hours a week exclusive of emergency duty, training, and inspection. Camp Croft used a 131/z-hour day, 6-day week, or 81 hours a week plus extras. Other variants at different hospitals produced the same general totals.28

These discoveries posed one of the most difficult questions to be encountered by the Army in its employment of womanpower: to what extent the Army could be bound by labor laws and civilian rules in the hours of work for women. Eighteen of the states had laws to the effect that 48 hours per week, or 8 hours per day for 6 days, were the maximum for women workers. In England, the Factory Act of 1937 placed the maximum for women at from 48 to 54 hours, and even in the darkest days after Dunkerque, the Ministry of Labour recommended that these hours not be exceeded. The U.S. Army Industrial Hygiene Laboratory, after a study of women in industry, reported:

[348]

One of the lessons learned in World War I and again after the collapse of France in 1940 was that excessively long hours of work do not ultimately pay, even when considered solely on the basis of output and apart from the effect on health .... All of the available evidence from England and this country indicates that working hours in operations involving a fair amount of physical effort should not exceed 60-65 per week for men, and 55-60 per week for women.

A committee representing the Army, Navy, Public Health Service, War Manpower Commission, Labor Department and other agencies had agreed in 1942 concerning either male or female civilians that "one scheduled day of rest for the individual approximately every 7 days should be a universal and invariable rule." 29

The Army Medical Department was therefore obviously exceeding all accepted safety limits in requiring a routine 72 hours a week and frequently 84 or 100 hours, and a 7-day week. On the other hand, the Army was in a somewhat different position from civilian agencies. Since it was entitled to ask a man's life in combat, it appeared equally entitled to ask that a woman sacrifice her health if required. There was a strong feeling in the Medical Department that any special regulations or labor laws concerning hours or type of work for women constituted discrimination; also, many Army doctors did not believe that any real damage to health would result. A representative of The Surgeon General stated, in refusing to accept the assignment of a WAC staff director for the Medical Department:

Some think that there has been entirely too much said on the subject of the physical capabilities of males vs. females and I can only say that I don't think any of them work as hard as they will when they become housewives and mothers.30

Director Hobby's recommendation, after she had considered the survey, was that any sacrifice was justified, either of health or life, if a true emergency required it; but that, since commanders did not deliberately kill men unnecessarily, the WAC should not unnecessarily sacrifice women's health. As a means of determining whether a true emergency existed, she proposed that the hours worked by Army nurses be considered the criterion. If nurses were not busy enough to require extended hours, and if the situation continued over months and years, there obviously was no emergency but rather a failure of hospital commanders to take aggressive action to improve personnel management. She therefore proposed that WAC and Nurse Corps hours be identical. This theory met with the general disapproval of hospital commanders, and was not to be acceptable for many months.

There was thus by the end of the summer of 1944 considerable doubt in WAC authorities' minds as to whether women should properly be employed at all in hospitals on an enlisted status, but should not instead be hired as civilians on a 48-hour week and with the privilege of quitting if overtaxed, a move that would also avoid the one-for-one replacement problem. To this was added the ethical question of whether recruiters were any longer justified in making commitments as to technical assignments which quite possibly would not be fulfilled.

Cessation of Medical Department Recruiting

Any such decision was postponed when, in late September of 1944, WAC recruiters

[349]

received a request from The Surgeon General to discontinue the Female Medical Technicians Campaign. At this time, some months before the Battle of the Bulge, war news seemed good, and on the basis of low casualty estimates from overseas The Surgeon General believed that adequate hospital personnel had been obtained. Recruiting of paid nurses' aides was also scheduled for suspension; recruiting of nurses lacked only a few hundred of meeting the original ceiling. On the basis of similar reports from other agencies concerning the approaching end of the war, the entire WAC Recruiting Service made plans to go on a maintenance basis at the end of the year.31

It was thus prematurely hoped that a clash between procurement and medical authorities had been avoided for the duration. Surveyors, reporting finally in October, believed that they had corrected half of the cases of broken recruiting promises, and others were scheduled for correction if and when discovered. The ASF was not willing to take further action at the moment, since this "would harass commanders . . . corrective action is not now advisable'"; it was hoped that time and the end of the war would bring the necessary readjustment.32

Resumption of the offensive in Europe brought greatly increased casualties, plus heavy hospitalization from combat fatigue, exposure, and trench foot. In one month the Army received more casualties from overseas than it had in all other months since Pearl Harbor, and soon the sick and wounded were being returned at the rate of 20,000 monthly. Almost overnight the situation regarding future medical care changed from comfortable to desperate.

A re-evaluation of the Nurse Corps ceiling indicated that installations in the United States would be short more than 8,000 nurses; only 41,839 nurses were in the Army, 75 percent overseas, of the 50,000 now believed needed at once. Also, although the Cadet Nurse Corps had absorbed some 177,000 young women and $192,285,518 in appropriations, it was chiefly designed to meet civilian nursing needs and had at this time furnished the Army only a few hundred cadets. In a final blow, more than 5,000 general service enlisted men were again ordered transferred from the Medical Department to make up Army Ground Forces casualties. This was the situation when, on 16 December 1944, the Battle of the Bulge began.33

At about this time a number of drastic measures were taken simultaneously by the Medical Department, any one of which would have been adequate to meet the situation that actually developed. In spite of certain objections from the General Staff, the Nurse Corps ceiling was raised to the total of 60.000 recommended by The Surgeon General. The Surgeon General on 19 November assured the Secretary of War that the nursing situation was "nearly hopeless." In an effort to arouse both the public and the General

[350]

Staff to his needs, he went so far as to bypass the Bureau of Public Relations to give alarming statistics, based on the new Nurse Corps ceiling, to a well-known columnist. Great national concern resulted. Near the beginning of the new year, a proposal to draft nurses went from the Secretary of War to the President, and from him to Congress. Meanwhile, to fill the immediate gap, plans were made for the Red Cross to recruit 5,000 more nurses' aides. And even earlier, on 15 November, The Surgeon General's Office discussed plans to reverse the decision on WAC recruiting and to request some 8.000 more Wacs.34

Exact plans for these 8,000 WAC recruits developed slowly during the last six weeks of 1944. At first The Surgeon General, Maj. Gen. Norman T Kirk, after receiving the pledge of higher authorities to do everything possible "to strengthen Kirk's hand,"35 asked for 8,500 enlisted medical and surgical technicians, either men or women. It was stated that each could fill a nurse vacancy by assuming enough routine nursing duties to permit one nurse to handle the professional duties of two. For each of these men or women, The Surgeon General asked a rating of T/4, or sergeant, as befitted the skills involved. After discussion, both The Surgeon General and the Army Service Forces recommended that all of the technicians be Wacs, since the limited service men available for retraining seemed chiefly interested in getting out of the Army, and it was felt that women would have more enthusiasm for caring for the wounded in the long hospitalization and rehabilitation period ahead. Again the Medical Department asked for women in the upper AGCT and educational brackets.36

The Service Forces immediately authorized their hospitals to carry one WAC medical technician overstrength for each unfilled vacancy for a nurse. No announcement was made to the field as to how these extra technicians would be obtained, or whether they would get the T/4 rating previously recommended by The Surgeon General.37

Over this point, the General Staff disputed during the last days of 1944. Directives to curtail all WAC recruiting went to the field on 20 December, and an immediate decision was necessary if they were to be recalled. Resumption of the Female Medical Technicians Campaign would have been simple, but Director Hobby was not willing to sponsor a drive to induce highly qualified women to enlist unless some better assurance could be made that recruiting promises would be fulfilled. She sent The Surgeon General a list of questions concerning the means of providing the guaranteed job and grade, and in reply was assured only that the hospital training would be very valuable and would give the women an excellent chance, after the war, of being hired by the Veterans' Administration.38

The temper of the moment was one that made refusal to recruit for the purpose unthinkable. Director Hobby's telephone

[351]

conversations revealed that she shared the general belief that "those boys are being wounded without people there to do things for them." Nevertheless, she cast about for any alternative to sending more women on enlisted status to Army hospitals. She went so far as to suggest in high places that nursing standards were too high, and that rather than use Wacs with a few weeks' training, the Nurse Corps should employ, as warrant officers or on a similar status, the practical nurses and graduates of smaller nursing schools who were not acceptable for commissions. This, she was informed, was impossible because of the pressure of civilian nursing groups against recognition of such women. Plans to recruit more Wacs therefore continued.39

Director Hobby's concern over the situation was such that she went in person to General Marshall to record her protests. General Marshall shortly thereafter interjected into the War Department conferences an opinion that sufficient women of the high caliber desired could not be recruited by the WAC for these jobs unless the Army could back up its guarantee of work involving patient care and a rating. Unless these could be assured the recruits, General Marshall refused to sanction any further recruiting of women as medical or surgical technicians.

Since such assurance was impossible under the current system, he proposed that the new Wacs be sent to hospitals in Table of Organization companies. The rigid T/O unit came equipped with its own extra allotment of grades, and with specifications as to the exact job of each member; neither the job nor the grade could be changed by field commanders. Such units for women had long ago proved impracticable for general duty Waacs, since few stations could use identical inflexible units, but general hospitals were a different matter, since all had almost identical missions and organization, and all used technicians.40

Before such units could be authorized, Director Hobby became aware of another fact which again caused her to consult General Marshall: The Surgeon General was asking the Red Cross for 5,000 civilian nurses' aides to be recruited at the same time that the WAC would be recruiting its 8,000 enlisted technicians. WAC recruiters feared that no WAC campaign, even if it guaranteed a good job and a rating, could succeed in competition with Red Cross offers of higher pay and officer privileges for identical jobs in identical hospitals on a civilian status. Instead, recruiting funds would be wasted and the government placed in an indefensible position.

On 5 January 1945. General Marshall wrote to his deputy, Lt. Gen. Thomas T Handy:

I have just talked to the Director of the WAC and she tells me the ASF is

going after 5,000 nurses aides.

My guess would be that this will ruin what I want to do in creating General

Hospital companies in the WAC organization, because of the pay status and

general competition with the Red Cross ....

Please look into this business and see that we are not working against ourselves

in this enterprise. I want action.41

The decision between Wacs and nurses' aides at once involved the War Depart-

[352]

ment in much bitterness and misunderstanding. In training, the two positions were virtually identical, although graduates of the Red Cross course were considered by The Surgeon General to be "not as well trained" as WAC graduates of the Army's six-week course, and often needed retraining.42 In relative cost, also, the WAC appeared to have a slight edge. A study made by the Chief of Staffs office indicated that a Wac cost from $1,032 to $1,368 yearly, including pay, housing, food, and clothing, while a civilian nurses' aide received $1,752 to $2.,190 for a 48-hour week.43

However, civilian advocates of nurses' aides noted that there were always many hidden costs to military personnel and that the Red Cross bore the cost of recruiting and training aides. Army Nurse Corps leaders preferred civilian aides, stating that nurses would be needed to train Wacs, that Wacs were subject to redeployment, that WAC officers had been given Army rank a year before nurses, and that women under WAC command would be subject to call for drill without regard to patient care.44

In making its decision the War Department considered all of these arguments of less consequence than the decisive one: Wacs could not quit when the shooting ended. G-1 Division stated:

Since the personnel necessary for the care of the sick and wounded in Army hospitals must be available not only during the next . . . months but throughout the period when the Army hospitals must care for and rehabilitate all men wounded during the war, it is considered essential that a sufficient complement of military personnel, enlisted for the duration plus six months, be available.45

Breaking off with the Red Cross aide program proved a delicate business; the Red Cross for many years had been accustomed to recruit Army nurses as well as aides, and to set the. standards of acceptance. Since Red Cross officials objected on the ground that commitments had been made to women already in training, it was agreed to hire all of these before discontinuing the program. 46

Red Cross leaders co-operated in agreements by which their graduates might be guaranteed a medical technician rating without further training if they enlisted in the WAC. Resentment within some of the Medical Department offices was longer-lived. After the end of the war, Training Division, Surgeon General's Office, stated in its history that the Medical Department had never requested the 8,000 Wacs at all, or planned to use them, until Director Hobby had exerted influence upon General Marshall to cancel civilian nurses' aide recruiting, thereby forcing the Medical Department to take Wacs "to meet the shortage thus created." 47

T/O Units for General Hospitals

Upon receipt of General Marshall's demand on 5 January, G-1 Division called from their evening meals WAC Deputy

[353]

Director Rice and representatives of The Surgeon General, in various stages of off-duty attire, and the group worked all night to deliver to General Marshall the completed plan for WAC hospital companies.48

The Table of Organization, details to be prepared later by The Surgeon General's Office, was set at 100 women, in an assortment of technical and clerical jobs believed to be adaptable to any general hospital. Since no member was to be less than a skilled technician or clerk, no rating less than T/5 or corporal was included-a slight decrease from The Surgeon General's estimate that a T/4 or sergeant would be required for each, and one which gave the new units no higher spread of grades than that of men already in Army hospitals. Any hospital desiring one or more of such companies was to report the fact, and the women would then be recruited with complete assurance of assignment to that hospital and to a technical job, which would if successful automatically carry a T/5 rating.49

G-1 representatives pronounced the T/O an excellent idea, which would not only permit recruiters to make foolproof guarantees, but would also prevent hospitals from frittering away, in luxurious station overhead, personnel given them to care for the sick. The chief of G- 1's Personnel Policy Branch stated later:

These units were developed to furnish medical and surgical technicians and other specialists in the hospitals, to assist the nurses. They were not developed for the overhead personnel of the hospital. Their purpose was to assist and care for the wounded and sick.50

To prevent injustice to women recruited earlier, the plan required that every Wac already working at such a hospital be incorporated into the T/O unit, or be transferred from the hospital if she was deemed incapable of performing a technician's duties. Pursuant to this scheme, The Surgeon General's Office was required on the night of 5 January to report the number of Wacs already at each hospital, which was subtracted from the number to be recruited to fill the unit. It was therefore confidently anticipated by planners that the establishment of the T/O units would remedy two ills at once: it would remove women from work as hospital orderly, which was officially considered beyond women's strength, and it would redeem all recruiting promises, past or future. The question of hours of work was also resolved by War Department approval of a circular requiring the same hours for all military women, commissioned or enlisted. Last, but far from least in the minds of enlisted women, the Director eventually secured authorization for a hospital uniform, a becoming rose-beige chambray, which could not be worn by civilians.51

Because the women had to reach the hospitals simultaneously with the peak of returning casualties, the General Hospital Campaign was launched almost at once. Women were required to have a score in the three upper AGCT brackets. White House co-operation was extended when Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt invited Colonel Goodwin to share a press conference in

[354]

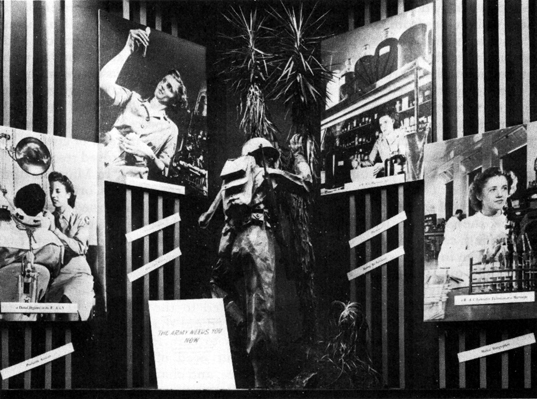

MEDICAL RECRUITING DISPLAY

January, and General Marshall again wrote to all state governors, seeking their aid.52

The appeal of nursing jobs to women was reported as "terrific," even in what the public now knew were the last days of the war. The General Hospital Campaign was soundly backed by public relations authorities, with numbers of local stories such as "WOUNDED APPRECIATE HELP," and effective local stunts. For example, Fitzsimons General Hospital received a giant bell, which toured Denver, tolling every eighty seconds to mark the return of one more American battle casualty who needed care.53 A quota of about 6,000 by 1 May was set; in mid-career it was raised to 7,000; yet recruiters met and passed the number by the end of March, a month ahead of schedule.54

Training also went off well. The Third WAC Training Center at Fort Oglethorpe was turned over to medical recruits, and a shortened basic course was followed by a six-week medical course on the same post,

[355]

staffed by Army doctors, nurses, and enlisted technicians from nearby hospitals. Both students and training authorities had only praise for the excellent and practical course and for the instructors.55

The recruits themselves were a promising group, extremely enthusiastic. Many were motivated by the fact that relatives had been casualties; they wished to give to some wounded soldier the care they had not been able to give personally to their own wounded. The majority were young single women of good character and intelligence; they successfully completed the three-month course in six weeks, with few failures even in cases where women with lower-than-qualifying AGCT scores had been erroneously recruited. About 5,000 were graduated as medical and surgical technicians, and 1,300 as medical clerks.56

However, the difficulties inherent in the whole General Hospital Campaign became obvious even before the women reported for duty. The Surgeon General's representative stated:

Utter confusion and conflicting policies and directives re ideas as to the utilization of this personnel have been flagrant since the original idea of WAC Table of Organization companies was conceived.57

Because of the confusion, repeated conferences were held with Director Hobby and with medical officers from every service command, without much success. Although the hospital T/O had been drawn up by The Surgeon General's Office itself, that office believed that changed conditions merited abrogation of recruiting commitments.

Even before the new recruits reached the hospitals, the Battle of the Bulge was won and January's fright concerning medical care was in the past. Just as V-E Day was in prospect, all of the drastic attempts to get medical personnel were embarrassingly successful and bore fruit simultaneously. The nursing profession, under threat of the draft, had responded with a rush; in the three weeks between 8 and 29 January 1945, over 10,000 applications for commissions were filed. Draft rumors also stimulated 60 percent of senior cadets to choose the Army instead of civilian employment. Hospitals proved resourceful in hiring civilian nurses. In May, the director of the Army Nurse Corps, Col. Florence A. Blanchfield, returned from Europe to find that there were actually too many nurses. She recommended that 2,000 civilian nurses be released, and secured a recall of the proposed draft legislation. As a result, hospital commanders everywhere objected to the WAC T/O units, and pointed out that they no longer needed Wacs to care for the sick, but were in urgent need of more orderlies, kitchen police, and charwomen.58

The matter of grades was also a disappointment. It had been guaranteed by G-1 that these would be an extra allotment, but when the ASF appealed to Lt. Col. Westray Battle Boyce, the G-1 WAC officer handling the grades, it was in-

[356]

formed that "you must find them," and, after further appeals, it was six months before these were forthcoming from G-1 Division.59

Meanwhile, men and women already in hospitals felt that the new recruits were receiving their grades. They also failed to realize that the T/O grades were no higher than those already allotted hospitals, the only difference being that in the new units every member received a low rating at the expense of fewer high ratings than men in hospitals possessed. In any case the new arrivals could be promoted at once under the T/O while older hands had to wait for a vacancy in the existing overstrength.

The Air Forces solved the problem by getting War Department approval to the promotion of every Air Forces medical technician, man or woman, to the merited grade of T/5 regardless of other overstrength, but The Surgeon General asked instead that the situation be equalized by not promoting the new recruits. The Surgeon General's representatives privately admitted that they had concurred in setting up the T/O with rated technicians, and that "'some of the things that you and I object to most strenuously were recommended by The Surgeon General's own office." Nevertheless, SGO Training Division now proposed that hospitals be freed to utilize the new recruits in any duties in which they were most needed, and to promote them on the same basis as other personnel. It was also proposed that some 1,800 recruits still in basic training not be given the technical training they had been promised, but be sent at once to unskilled work." 60

Director Hobby opposed this plan on the grounds that recruiting promises made to women and affirmed by their state governors at the request of General Marshall could not be broken. The Surgeon General's representative objected:

Colonel Hobby has the idea that every company should be exactly as the Table of Distribution prescribes .... This is an unrealistic and impossible point of view .... In one breath, the theme of G-1 and the Director WAC appears to be to give the Surgeon General what he wants and needs and the next is to say that the Surgeon General will take what they give.61

Nevertheless, on this point the War Department's final decision was that recruiting pledges could not be broken.62

Even greater opposition from The Surgeon General's Office was offered toward the plan to assign all hospital Wacs to these companies. The directive produced after the all-night planning session of 5 January had stated specifically, "The WAC personnel now on duty at General Hospitals will be absorbed into the companies within the T/O strength." The Army Service Forces reported to the General Council as late as 13 March that the personnel on duty at general hospitals would be included in these units and be given at least 90 days to qualify for grades. On the next day it developed that the Office of The Surgeon General had not been aware of this clause; representatives also denied seeing The Adjutant General's

[357]

letters to the field that set up the companies on this basis. The Surgeon General had even issued contrary directives saying that WAC orderlies would be retained. On this point, since there had been no public commitment, Director Hobby was overruled and the directive rescinded. 63

The general hospital T/O units lasted less than a year. Shortly after the defeat of Japan The Surgeon General obtained their dissolution on the grounds that they were too large for the decreasing size of hospitals, and would hinder demobilization. Wacs in these companies remained at hospitals as part of the regular bulk allotment, but the General Staff required, before permitting inactivation of units, that every woman receive the rating promised her. Thus the general hospital recruits could finally be used on any duties, as desired by The Surgeon General, but at least they had corporal's stripes.64

Final reports from inspectors in the last months of the Corps did little to dispel doubts concerning the suitability of hospital employment for women on an enlisted status. There was no doubt of its suitability for women on some status. The care of patients held an attraction for them, and even when Wacs were allowed officially to do nothing but scrubbing and cleaning, they devoted off-duty hours to the patients. writing letters, reading, shopping for them, and running various errands. Hospital commanders with few exceptions praised the work of Wacs to inspectors even while objecting to restrictions imposed by recruiting commitments. One said, "I'd rather have one Wac than three civilians.65

Final developments gave little indication that Medical Department policy could change to the extent necessary to protect the health of women in an enlisted status. In spite of the War Department circular requiring the same working hours for enlisted women as for nurses, the 12hour day continued. When inspectors found women at Walter Reed Hospital working an 80-hour week long after the end of hostilities, the commanding general stated frankly that he had "circumvented the provisions of the circular by putting a small number of Army nurses on 12 hours duty."

The prominent women of the WAC's National Civilian Advisory Committee visited general hospital companies at work, after the Chief of Staff had overruled objections to the visit from both ASF and The Surgeon General; they reported themselves shocked at conditions. Barracks were frequently crowded, ill ventilated, and sprinkled with coal dust; workers on all shifts used the same bar-

[358]

racks, disturbing those trying to sleep either day or night; and hours had not greatly improved, with women still required to train and frequently to launder their clothing on their own time. There was also no evidence that the practice of malassigning technicians had abated. General Dalton eventually lost patience with repeated violations, and Colonel Goodwin ascribed to him personally most of the credit for redeeming such broken commitments as were redeemable.66

By some coincidence, the Navy reported the same experience, and the director of the Bureau of Naval Personnel stated later:

Experience indicated that in some jobs too much was asked of the women's physical strength. Oddly enough, the outstanding offender was BuMed . . . . As evidence mounted of women breaking under the strain of long hours, the office of the Women's Reserve put increasing pressure on BuMed to remedy the situation.

A 51-hour work week was regarded by WAVES authorities as "the desirable maximum," but the Bureau of Naval Personnel reported, "Efforts to have this cast in the form of a directive failed to overcome the opposition of Naval tradition against 'union hours.67

Final recommendations by the Army Medical Department confirmed the fact that continued utilization of servicewomen was contemplated by Army hospitals. For commissioned positions, The Surgeon General asked and obtained legislation to allow women to be commissioned directly in a women's medical specialists corps, headed by its own colonel, which would include dietitions. physical therapists, and occupational therapists.

The Surgeon General also advocated that enlisted women who worked in hospitals be enlisted in the Medical Department alone and not in the WAC. This move would have obviated the requirement for a WAC company commander and for compliance with War Department restrictions as to the hours and types of duty for members of the WAC. The War Department did not look with approval upon any such proposal for the setting up of independent women's corps in the different administrative and technical services, which tended toward compartmentalization as opposed to integration; it also did not agree to abdicate its Army-wide responsibility for safeguarding the well-being of women. Medical Department utilization therefore continued upon the wartime terms and without much greater clarification of the situation than had hitherto prevailed.68

[359]

Page Created August 23 2002