CHAPTER XX

The North African and Mediterranean Theaters

The North African Theater of Operations was the pioneer in employment of Waacs overseas.1 The experiment owed its impetus to the first theater commander, Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had been impressed with the efficiency of British servicewomen, and to his deputy, Maj. Gen. Everett S. Hughes, who fifteen years before had prepared the General Staff study, Participation of Women in War. On most lower echelons there was a less favorable general attitude, ranging from mild skepticism in headquarters offices to bitter opposition in the great majority of soldiers' letters.2

The theater received its first five WAAC officers on 22 December 1942, some six weeks after the invasion of North Africa. The women, qualified as secretaries, were assigned by the War Department to England, but upon General Eisenhower's request were immediately placed by the London headquarters on a ship bound for North Africa. A day out of port, the ship was torpedoed, and the women came into port aboard a British destroyer, which had taken two from the burning ship and three from a lifeboat. The day in the lifeboat was remembered by the Waac participants as a hectic interval in which they lost all their equipment, the only crewman aboard became violently seasick, and the women fished five or six men, one badly injured, from the water. When the Waacs arrived in port, dirty and bedraggled, they were greeted by anxious dignitaries who contributed oranges, toothbrushes, and other emergency items. General Matejka offered half a jar of hand cream, while Maj. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith procured small-sized men's trousers, which the women found they could not get into. General Smith immediately chose as his assistant one particularly filthy member who had lost hairpins and hat and been vomited on; he confided to her later that he "picked the worst-looking so her feelings wouldn't be hurt." The greatest con-

[360]

tribution came from General Marshall, who met the women at the Casablanca Conference and took home a list of lost equipment. Finding that there was no legal means of free replacement, he personally paid for and forwarded new clothing, refusing to accept repayment.3

The first enlisted women arrived in the theater a month later. The 149th WAAC Post Headquarters Company, called by newspapers "the first American women's expeditionary force in history," was one of the most highly qualified WAAC groups ever to reach the field. Hand-picked and all-volunteer, almost all members were linguists as well as qualified specialists, and almost all eligible for officer candidate school. The company was shipped from the United States on a regular military transport, which encountered no enemy action. The only difficulty was the loss of unit equipment, which never arrived in Algiers. The unit's vehicles were later found to have been issued to a male unit at the port, while cooking equipment, medical supplies, folding cots, recreational equipment, typewriters, and clothing maintenance supplies vanished, a serious loss in view of shipping conditions and the absence of women's supplies in theater warehouses. Such occurrences in later shipments were to be prevented by the prior appointment of a theater WAAC staff director to make advance preparations.4

The unit reported on 27 January 1943 to General Eisenhower's headquarters in Algiers, a location now considered safe, except for air attack, from the conflict still raging to the east. The women were housed in the dormitory of a convent school some distance from the headquarters. The unfamiliar climate and the unheated quarters caused almost every member to succumb immediately to colds and other respiratory disorders-a tendency noted also in newly arrived men. Waacs washed in an outdoor trough, carried water in helmets, and worried in their usual manner concerning the impossibility of careful laundry or neat appearance. Working hours were long; women were carried in trucks to the headquarters at an early hour, and home again for an early curfew. The nightly bombings, with brilliant displays of antiaircraft fire, made sleep difficult for the first weeks.

Nevertheless, most women managed a satisfactory adjustment, and most of the sick required no hospitalization.5 Morale was high, and women called themselves the luckiest in the Corps, commenting variously, "Life has been one thrill after another"; "All my life I wanted to travel and see strange sights and now I am doing just that"; and, of the ack-ack fire and burning barrage balloons, "No Fourth of July celebration could be more spectacular.6 Ecclesiastical authorities protested when Wacs were housed in church quarters, but soon admitted that they had "never imagined that a unit of American women could be so well-disciplined and so considerate as well." 7

[361]

As there were not enough Waacs in this first unit to supply every office's needs, the theater adjutant general reported an "inevitable scramble by chiefs of general and special staffs to obtain additional WAAC personnel.8 The largest part of the company went to the Signal Corps and to the newly organized Central Postal Directory. Others were assigned, by twos and threes, to various headquarters offices: three to the Office of Psychological Warfare; three to the adjutant general's office; one as General Eisenhower's secretary and one as his driver; more than a half dozen to drive other officers. Ten more were assigned as cooks and bakers to keep food ready for workers on three shifts.9

Reports on initial job success were consistently good. Among the first to receive commendation were telephone operators and other communications workers in theater headquarters. The Voice of Freedom-the entire telephone switchboard system of theater headquarters, large enough to service a good-sized city-was eventually manned entirely by WAAC supervisors and operators. Many telephone operators had from ten to fifteen years of civilian experience as operators and supervisors, and some were bilingual. A record for calls handled was set, and the theater chief signal officer, Brig. Gen. Terence J. Tully, stated, "It is highly desirable that the use of Wacs be extended," particularly to message center and cryptographic duties.10

The first postal directory workers were likewise successful. Officers in charge reported that "since the Waacs have taken over with an entirely different attitude toward the job than the men who had previously handled it, the percentage of errors has decreased materially."11 Although the job was considered by some to be a deadly routine, Waacs were somewhat romantically apt to visualize the pleasure of a soldier in getting long-delayed mail, or the anguish of a mother erroneously returned her letters, stamped "missing in action.'' The postal directory's Army supervisor stated:

The office was piled ceiling high. These girls came in and took over and worked from 8 a.m. until 9:30 p.m. seven days a week until it was cleaned up . . . . days never thought of asking for time off and I had to order them home nights. 12

This early and continued job success was deemed remarkable in view of the administrative difficulties that the unit encountered during its first six months. Theater authorities attributed the confusion that developed to the absence of a WAAC adviser on the staff level, for the women had been sent without a WAAC staff director for the theater-the first and last time that such a mistake was made.13 In the meantime, certain policy questions had arisen which even General Hughes, with his long study of the problem, felt unable to answer. Ire sought Director Hobby's advice by mail, but she felt it undesirable to attempt long-distance pronouncements in ignorance of local conditions.14

[362]

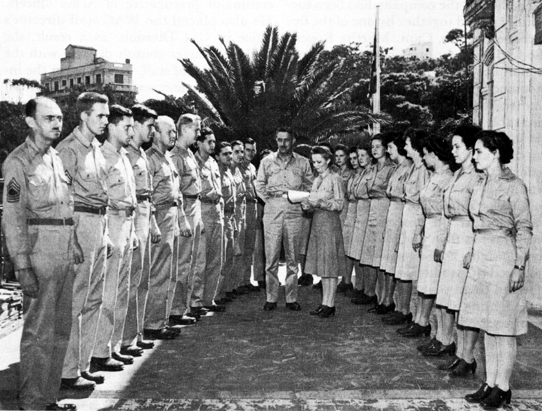

MAJ. WESTRAY BATTLE BOYCE, WAAC Staff Director, North African Theater, reads orders replacing enlisted men of the adjutant general's office with enlisted women, Algiers, North Africa.

Finally, responsible commanders in the theater were stirred to action by the report that a large number of Waacs did not intend to enlist in the WAC. At this, General Eisenhower cabled a request for "a highly competent senior WAAC officer to be sent to this theater without delay.15 Director Hobby promptly complied with the request and sent a theater WAAC staff director. Maj. Westray Boyce, previously staff director of the Fourth Service Command. Major Boyce, according to General Hughes' account, "arrived to find the girls in a state of mind which required immediate and drastic action. This she took."16 The previous company officers and key cadre were returned to the United States in a body, since it appeared impossible to place individual responsibility or to restore the women's lost confidence; all later proved successful in a variety of duties in the United States. A request was cabled for "competent, experienced" company officers to fly to the theater.17

[363]

Meanwhile, the company had been successfully pulled together by one of the five officer secretaries, Capt. Martha Rogers, who had not been previously considered for company duty for lack of "voice and command" presence. Major Boyce secured some reassignment of women who were unsuitably assigned or not kept busy. She also succeeded in slowing up the promotion of Waacs, which she felt that a few section chiefs had been making too indiscriminately. After the reorganization, morale soon improved, and the number of Waacs lost at the conversion to Army status was less than had been anticipated. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower personally addressed the women in mid-August and informed them that they were necessary to the fighting ahead, and that "if a single one of you goes home, it's too many." 18

Because of the general alarm at the results of lack of staff supervision, General Eisenhower and General Hughes personally drafted and put into effect a system that gave Major Boyce greater power than any ever held at any other place or time by any other WAC staff director. Under the title of Theater WAC Executive Officer, she was given virtually complete command jurisdiction over Wacs in the theater, bypassing normal military channels in all matters except supply and routine post administration. She was supreme on all matters of promotion, job suitability, discipline, discharge, and well-being. In fact, the system was a complete reversion to the old WAAC regulations, although few WAAC officers in the United States had ever exercised all of these powers as fully as Major Boyce now did.19

These powers did not last long, for a new commander Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, replaced General Eisenhower a few months later, and soon restored the command prerogative of Army officers. He also placed the WAC staff director's office in G-1 Division; as a result, she could no longer consult directly with the deputy chief of staff: However, in the interim, the theater staff had become accustomed to consulting the WAC staff director on policy matters, and the habit persisted even after WAC command powers were revoked and after Lt. Col. Westray Boyce was succeeded, in less than a year, by Lt. Col. Dorothea A. Coleman. The headquarters eventually directed in writing that the WAC staff director be allowed to comment on all matters affecting Wacs before action was taken by any headquarters division.20 With this precaution, it appeared to be a matter of little moment what command system was used, and the early administrative problems seldom if ever recurred in later units.

From the time of arrival of the first unit, theater requisitions for more Waacs had been repeatedly forwarded to the War Department, with the highest shipment priorities. As soon as approaching military status warranted, these began to be shipped, in accordance with General Marshall's policy of priority to combat theaters. The second shipment arrived in May, some four months after the first, and contained chiefly workers for the Central Postal Directory, although fewer than the chief of that agency had tried to obtain. In August of 1943, a platoon of about

[364]

sixty members arrived in Casablanca and proceeded to Mostaganem for service with the Fifth Army. In September the 60th WAC Headquarters Company arrived to augment the 149th, and the 61st for SOS headquarters at Oran.21

The need to release more men to staff Signal Corps installations in Italy brought about the activation of a complete WAC Signal company, which arrived in Algiers in November. The women were welcomed by the Deputy Chief Signal Officer, Allied Forces Headquarters, who promised them long hours of work under "far from ideal conditions.22 Members were assigned as route clerks, high speed radio operators, teletypists, cryptographic code clerks, and to cutting tape in radio rooms. On the same ship with the Signal company was the first WAC contingent for duty with the Air Forces in the theater, the Twelfth Air Force Service Command at Algiers. This unit was picked up at the port of debarkation by transport planes and flown direct to its parent organization. According to its chief of staff, We have a lot of work for them to do right now; we can't afford to have them sitting around a port for several days.23 Enlisted members; like those in preceding shipments, were again highly qualified, ranging from a former dean of women to a translator of African dialects. Most were assigned as telephone operators, file clerks, typists and stenographers, and to aid in the air service command's work of forwarding ammunition, engines, and other supplies to the front.

In January of 1944, the theater announced the arrival of another contingent for service with the Air Forces-some 372 enlisted women and eight officers, bringing the theater total to over 1,500. These were divided into four units for assignment to four different stations in North Africa. Other shipments continued during 1944, eventually bringing the theater total to approximately 2,000. The theater thus assumed third place in the number of Wacs employed overseas, being eventually surpassed only by the European and Pacific theaters.24

These Wacs were processed in and out of the theater by a WAC replacement depot, operated in conjunction with the men's depot, but with its own experts in WAC clothing, equipment, records, and other processing. Here new arrivals were given orientation talks by the WAC staff director, with hints as to how best to profit from the past experiences of Wacs in the theater. New arrivals were interviewed and assigned by a WAC specialist in G-1 Division, who was aware of the probable training, capacities, and limitations of WAC personnel.25

Even before the full 2,000 had arrived, Wacs had begun to move out into Italy, beginning with the Fifth Army platoon in November of 1943. At the height of the Italian campaign there were fourteen WAC units with the various commands in Italy, including the Fifth Army, the Peninsular Base Section, and the Air Forces. By the end of the Italian campaign all of the theater's Wacs were in Italy.

[365]

WAGS ARRIVING AT CASERTA, ITALY, 17 November 1943.

The theater's most unusual experiment in WAC employment was that of the Fifth Army Wacs, who claimed the honor of being the first Wacs to set foot in Italy, and in fact on the continent of Europe. Although never more than sixty women were involved, the experiment was considered to be potentially more important than its size would indicate, since it might determine the degree to which women could in future emergencies make up part of tactical units.26

When the Fifth Army jumped off for Italy, the Wacs were not too far behind it, arriving in Caserta, via Naples, on 17 November 1943 under the command of 1st Lt. Cora M. Foster. The T/O called for 10 telephone operators, 7 clerks, 16 typists, 10 stenographers, 1 administrative clerk, and cooks and other cadre. In late January the unit split into forward and rear echelons, and the forward echelon, including all telephone operators and some stenographers, moved into the bivouac area near Presenzano. Here the women lived in pyramidal tents and worked chiefly in the Fifth Army's mobile switchboard trailer. By March the rear echelon was also in tents near Sparanise. Unit records noted

[366]

that the women "thrived on it; the sick call rate dropped way down.''

For the rest of the Italian campaign, the units followed the Fifth Army up the peninsula, usually being located from twelve to thirty-five miles behind the front lines. From June to September the forward echelon's longest stay in any one place was five weeks, the average being two. The women lived in whatever billets were available-schools, factories, apartments, and chiefly tents. The forward section spent most of the winter of 1944-45 living in tents in the mountains above Florence. The women usually wore enlisted men's wool shirts, trousers, and combat boots, and carried only the few necessities that could be moved forward with them.

The unit proved unusually successful. It received Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark's praise as well as being one of the few to receive both the Fifth Army Plaque with clasp, in 1944, and the Meritorious Service Unit Plaque in 1945. There were twenty-seven awards of the Bronze Star. The forward echelon included some of the most skilled telephone operators on the Continent, able in a matter of minutes to get through the complicated communications networks to the commanding officer of any unit sought by General Clark. The unit's morale and esprit de cops were perhaps the highest in the theater's WAC units. Its members wore the Fifth Army's green scarf. "They were," said Colonel Coleman, "Fifth Army first and Wacs second-perhaps the best-integrated unit in the theater."

The dangers of a combat area did not present any great problem in this case. During the last days in Anzio, air raids offered the nuisance of noise and falling shell fragments, but fortunately the area had just been vacated by a combat unit that had left adequate foxholes and dugouts. The Wacs were lucky in having no injuries, in spite of some close calls. During the advance up the peninsula, they were frequently within sound of long-range artillery, and almost always in an area of complete blackout, but required no guard except the: usual one that patrolled the entire camp. Italian service troops ordinarily set up the WAC and Nurse Corps tents, and the Wacs took them down themselves, with the aid of two Italian laborers to load them on trucks.

In spite of the fatigue that developed from repeated moves, officers noted that the women "griped and complained less than soldiers in rear areas." Signal Corps units in rear areas were surprised, upon offering Wacs rotation to less exhausting conditions, to find that not one telephone operator would agree to quit the Fifth Army unit.

WAC commanders credited much of the sustaining sense of integration to the personal policies of General Clark, who saw to it that a stirring ceremony was made of any occasion; such as the swearing-in of Waacs to the Army, or the presentation of medals and awards. When visiting dignitaries came to the area. Wacs stood honor guard with men of the 34th Division. Women were left in no doubt that they were considered useful and valuable members of the group. Such measures inspired a loyalty among the women that long hours, fatigue, and discomfort could not shake.

It was undoubtedly significant that Wacs under such circumstances seemed exempt from the pattern of administrative needs that was invariable in sedentary units. The almost total absence of grades and ratings did not noticeably affect morale, although an expert switchboard op-

[367]

erator of two years' service was lucky to get a pfc. rating. The longer hours, the lack of privacy, the necessity for wearing clothing designed for men, all seemed to have little effect. Telephone operators seemed to be immune from the illness and tension experienced by women on identical shift work in more permanent companies a few score miles to the rear. Rude remarks from occasional unfriendly males, which caused a morale problem among Wacs elsewhere, were more or less brushed aside by women too busy to notice them and too assured of their own usefulness to doubt it. Under the circumstances, the staff director considered it a pity that all Wacs could not be employed in such units.

WAC advisers recommended that any such groups, for best success, be carefully selected. The best-suited type of woman was believed to be one whose physical stamina was average or better, who liked outdoor life, and who was well balanced mentally and emotionally. In a small isolated group, it was found fatal to include those with irritating habits and mannerisms -overtalkative, grouchy, or erratic. The ambitious or the highly qualified woman was also not a good choice, since top supervisory jobs in a tactical headquarters did not go to women, nor did they receive the high grades that those in rear areas did, many still being privates after two years. Emotional self-control was also vital, since the women were constantly surrounded by men, especially by combat troops coming back for a rest. Besides fending off advances, said the staff director, "The Wacs had to listen to the men and let them blow off steam, and this put an additional strain on the women's nerves." A mature woman was found preferable, especially one whose only interest was not the opposite sex. The lone company officer who accompanied each section had to be especially self-reliant and self-sufficient; her conduct necessarily had to be above reproach.

It was Colonel Coleman's final judgment that WAC units singular to this Fifth Army unit might easily be used, if necessary, in army and corps headquarters, or wherever nurses could be used, provided that the women were as well qualified. The only limitation, she believed, was that too many women should not be used in any one headquarters, since the headquarters force was also the security force, and lost a combatant for every woman specialist present.

With the exception of the small Fifth Army experiment, the remainder of the theater's Wacs were employed in ordinary headquarters duties not strikingly different from those in comparable agencies in the United States. Woman in Allied Forces headquarters and Services of Supply headquarters were employed by almost every staff section-ordnance, judge advocate, adjutant general, and others, and as secretaries to ranking officers. In addition, the headquarters of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces and the Twelfth and Fifteenth Air Forces employed Wacs, in units stationed at various times at Caserta, Bari, Foggia, and Florence.

In organization, the most distinctive feature in the Mediterranean Theater's employment of Wacs was that all women, with the exception of Air Forces and Fifth Army Wacs, were eventually organized into a single battalion under WAC command. This unit was the 2629th WAC Battalion, stationed in Caserta, under the command of Maj. Hortense M. Boutell. The battalion included a postal company, a message center company, a WIRES com-

[368]

pany, two headquarters companies, a replacement depot detachment, and a small Signal group on detached service, first in Constantine and then in Rome. Eventual enlisted strength totaled approximately 900, about half of theater WAC strength, plus 52 WAC officers, and some 400 British ATS attached to the battalion and housed with it. With such a large concentration of female personnel under WAC command, matters of supply, administration, and discipline were considerably simplified.27

In all units-Air, Ground, or Service Forces-the most striking difference from employment in the zone of the interior was the higher degree of skill and ability involved. All but a negligible number of enlisted women were qualified for skilled jobs; there were only two WAC "laborers" in the theater-one basic, one repairman. The statistically average Wac in this theater was a trim, healthy young woman, unmarried, older than the average soldier, with better education than the zone of the interior Wac.28 Thus, the theater never experienced the problems of the zone of the interior in assigning personnel of low aptitude or little training. The higher average ability was reflected in the final tally of WAC assignments in the various headquarters.29

| Type of Duty | Percent |

| Total | 100.0 |

| Clerical | 31.9 |

| Communications | 29.2 |

| Stenographic | 16.3 |

| Miscellaneous | 12.7 |

| Headquarters Cadre | 9.9 |

Such high percentages of skilled personnel not only made assignment easier, but minimized problems of maladjustment, mental health, discipline, and improper or too-heavy work. In most units women did not even have to perform kitchen police and fatigue duties, since local labor was available and it was considered uneconomical to waste a skilled Wac's time in such heavy tasks. The large WAC battalion alone eventually had about 250 civilian servants.

The advantages that the theater enjoyed in such high-type personnel were made clear by its reaction when, in later shipments from the United States, the quality declined somewhat, especially for officers, concerning whom an observer protested, "If we cannot give them officers who are outstanding leaders, we should at least give them officers who are ladies and whose conduct is such that the enlisted women can respect them." 30 A corresponding decline in the care of selection of enlisted women more than doubled the number who promptly had to be returned to the United States because of physical breakdowns.

The only major problem in WAC employment encountered by the theater was that of the Signal Corps Wacs.31 By midsummer of 1944, women in this work began to suffer from fatigue and depression; their sick rate was twice as high as other Wacs', and morale was low. The theater chief signal officer diagnosed the fatigue as "resulting from working long hours over a period of several months

[369]

under pressure caused by the necessity for speed and security in handling messages, and the realization of the operational importance of every duty they perform." WAC and Medical Corps officers felt that the difficulty was due, not to the work itself, but to the lack of leaves or furloughs, the rotating shifts so short that sleeping habits never became adjusted, and the long hours of off-duty training in other Signal Corps work. Most important was the shift work; Major Boutell later surmised that this alone was the chief problem, coupled with the lack of privacy or quiet in living quarters, which made sleep difficult for night workers.

By mid-1944 about 8 percent of the women who had been in Signal Corps work for a year or more were found already unfit for further overseas service, and others were, in the opinion of their commanders, building up a nervous tension that in time would permanently end their usefulness unless transfers or leaves could be arranged. The theater chief signal officer was unable to suggest any remedy except to try to enlist large numbers of Wacs for Signal Corps work with the promise that they would be discharged after two years in the Army. He also felt that, if a 2 percent overstrength of personnel could have been provided the Signal Corps by the War Department, the Signal Corps could have permitted rotation and leaves for all personnel. Major Boutell was of the opinion that there was no real solution for the Wacs unless one could be achieved by the Signal Corps as a whole.

With this exception, there could be no doubt that most of the women were happy in their overseas assignments; they commented variously: "I love my work and enjoy being overseas"; "I wouldn't miss being here for anything"; "I like being close to the war"; "I wouldn't change places with any girl back home." One said:

Many wonderful things happen to us. We've sailed the seas as other troops have, served on foreign soil, marched in Allied Nations parades, have seen and met some of the world's most famous men.

Another wrote:

Mother, I have never before had the complete satisfaction of worth-while accomplishment that I get from my present work. And I greatly doubt that I shall ever be inspired to put such wholehearted energy and effort into anything which my life after the war will demand of me.32

There was considerable debate, as in most such theaters, whether special housing and security measures required for women outweighed their usefulness on the job. It was the opinion of the staff director that there was little truth to the allegation that women required extra guards. She added:

There was an M. P. at each barracks in the cities, but there was also one at the officers' club, the noncoms'' club, and all enlisted men's barracks, to keep out the civilians. Even where women lived in tents, they needed only the usual patrol.

The only objection, in her opinion, was that Wacs, on moving to new quarters, usually needed help in setting up bunks, latrines, and showers.

At no time was there any serious question of the ability of enlisted women to adjust to conditions of life in a theater such as this one. Possibly the greatest physical hardship was the usual absence of heat and hot water in the quarters,

[370]

whether tents or mansions. Except for this, the usual billet was comfortable-frequently an apartment house, school, or hotel, considerably more pretentious than barracks in the United States. Theater authorities closely co-ordinated housing assignment with WAC advisers, leaving to them the matter of determination of suitability. The theater consistently maintained the requirement that Wacs be assigned only in groups of fifty or more, in spite of attempts by numerous agencies to scatter them about in small numbers; this requirement, in the opinion of WAC advisers, greatly facilitated control of housing as well as of discipline.33

Wacs in North Africa or Italy were seldom long without items of clothing necessary to health, if not to comfort and good appearance. Because of the relative difficulty of maintaining a stock of women's clothing, men's clothing frequently had to be issued in emergencies. Women's supplies were hard to come by. Women went months without their full issue of clothing; large and small sizes were scarce, shoe repair slow, the stocking situation often critical. Post exchanges did not always have items needed by women. Hairdressing facilities were often inadequate, since the men's barbershops were of course of little use to women. Supplies forwarded to units near the front were often lost, particularly in the case of small units like the Fifth Army Wacs, whose usual supplies filled only a small easily misplaced box. "Some of the stuff was never found; I suppose it's still over there," commented Colonel Coleman.

It was discovered that women in all kinds of work did not have enough warm clothing. For many work-type clothing needs, neither regulation WAC coveralls nor seersucker work dresses were suitable. For lack of a warm soft work jacket, over-sized wool shirts were cut off and made into battle jackets. In meeting these various emergencies, theater headquarters permitted close staff supervision by WAC specialists. The theater was always quick to requisition available new items of clothing, and protested whenever such items appeared in the United States before theater Wacs had them.34

Health, Discipline, and Morale

Theater Wacs were never in danger of capture, although they were frequently in air raid areas. The WAC billet in Naples was hit in one bombing, but, as members commented, "it only knocked down the ceiling and one wing." Maj. Margaret D. Craighill, inspecting for the War Department later in 1944, noted no serious tension among enlisted women as a whole. She stated, "The medical service given to the WAC is excellent," consisting of two women medical officers on full-time duty, which included a monthly trip to all units for the required monthly physical inspection. The only defect in care noted by Major Craighill was the fact that "sick in quarters" was not permitted, resulting in many subterfuges by women with temporary menstrual disorders who did not wish to be hospitalized. Major Craighill reported:

Dysmenorrhea seems to be more frequent among both nurses and Wacs in this theater. Some who were never before subject to difficulty during menstruation now complain of severe pain. Reasons for this are not apparent; fatigue and constipation may be contributing factors.35

[371]

Administrative arrangements for WAC medical care, with minor exceptions, were pronounced satisfactory, with adequate unit dispensaries and beds in general hospitals. As a result, evacuation rates were not excessive, being somewhat less for Wacs than for nurses. As for time lost from work, the theater enjoyed the distinction of being one in which the annual noneffective rate for Wacs was less than the comparable nonbattle noneffective rate for men-about 2.7 per 100 strength for Wacs, and 3.6 for all personnel exclusive of battle injuries.36

The rate of venereal disease was so low as to be negligible, although for men in the area rates were frequently alarming and the disease endemic. Among Wacs, cases were pronounced by Major Craighill to be "very infrequent"-less than one per month, with only fourteen cases having been reported by the end of 1944. The rate of pregnancy was less than that in comparable civilian age groups in the United States, and quite similar to that of nurses in the theater. Although no records were kept as to marital status, it was known that more than half of such women were married, with the number of pregnancies increasing toward the end of the war as the theater began to provide hotel quarters for married couples.37

The number of courts-martial during the entire two and a half years; through June of 1945, was extremely small, records showing no general courts, only six special courts-chiefly for censorship violations and thirty-two summary courts for almost 2,000 women. WAC officers felt that "the worst disciplinary problems have been created by a few women who obviously should not have come overseas because of lack of adaptability or emotional instability." Some cases of misconduct were attributed to unhappiness about job malassignment.38

There was every indication that WAC morale was good in most cases. Company commanders considered morale to be almost entirely dependent upon full utilization of time and skills; one observed, "They wanted not only to be useful but to be inwardly sure of their usefulness." In cases where low morale did occur, such as in certain Signal Corps units, investigators were unable to find any bad effect from rough living conditions or lack of recreational facilities or the desire to return home; the only factor that had a definite effect on health, morale, and efficiency was that of job satisfaction.39

For the maintenance of morale, off-duty classes of interest to women were sponsored by the theater early in 1944, even before Director Hobby was able to get the U.S. Armed Forces Institute and other agencies to provide special courses for women. When rest camps and recreation centers began to be established to permit brief passes and furloughs for male troops, Wacs were included and were provided with living quarters, messing facilities, and quotas for such locations as Algiers, Capri, Rome, and later the Riviera, Venice, Switzerland, and Jerusalem. Although the average stay was only from three to five days, the rest was found to be a great relief from barracks life for women, and served in lieu of a convalescent hospital, which was not provided for women. For a restful evening off, WAC authorities, working with British women's services, were able to obtain adequate separate facilities for women's clubs, where women could enjoy an evening of

[372]

bridge, cooking, and feminine companionship. The theater also permitted the WAC staff director to call meetings of WAC company officers and to send them monthly news bulletins, in an effort to improve leadership and administration.40

In the matter of decorations and citations WAC units and individuals were also included. The WAC sergeant who had supervised theater telephone communications received the Legion of Merit from General McNarney himself in a retreat ceremony. General Eisenhower awarded the Soldier's Medal to a WAC private who saved a soldier from a pool of flaming gasoline, at the expense of severe burns. Other decorations and battle stars were not unusual. Grades and ratings were likewise generally good, except among Fifth Army and Signal Corps personnel, and by the end of the war in Europe only a few hundred women who had been long overseas were still unrated.41

Soldier opposition had possibly a worse effect on morale than it did in the United States, since not only the Corps' existence but its presence overseas was questioned. Even before the women's arrival, letters streamed homeward advising against enlistment, and afterwards came the mass pregnancy rumors which helped to inaugurate the slander campaign. Almost 100 percent of soldier comment was unfavorable or obscene. An Army supervisor noted:

That sort of thing has a direct effect on the morale of the girls over here because their families write to them and want to know if they are true . . . . It bothers me because I can see the effect on the morale, spirit, and pride of the kids working for me.

Early arrivals also had to face insults in the streets. One Wac, advising her sister on enlistment, noted, "How many times I've heard some GI call us dirty filthy names, names that I would never allow anyone to call me if I were a civilian." WAC officers excited even more resentment than enlisted women, chiefly when they outstripped men in rank or promotions.

From those soldiers who worked in offices with Wacs, or were stationed in the same vicinity, the comments tended to become more favorable. The women's military bearing likewise was praised. Soldier comment noted:

As the girls came down the boulevard, they really drew the applause. You have to hand it to them, they look good on parade. I doubt if West Pointers could appear better.

Unfortunately, only a minority of soldiers ever worked in offices with Wacs, or had any opportunity for becoming acquainted with them. Even where soldiers and Wacs were stationed in the same cities, there were not enough Wacs to permit much firsthand acquaintance between the two. Women shortly became so surfeited with requests for dates that it was necessary to provide separate recreation rooms and snack bars where they might relax and enjoy feminine companionship. The conduct of combat men, particularly young Air Forces officers, was a problem, for, said the staff director, "They would just sweep into the dayrooms and take over the place, and nothing could be done with them." There was no doubt that a Wac date, where available, meant much to many American men. One wrote:

[373]

Some of the boys and I have been dating some Wacs and having a grand time. They have a day room all of their own with ping-pong table, darts, and cards. They have a small library too. About eleven o'clock in the evening they get some sandwiches for us at the mess hall and we polish them off with a couple of cokes. They are a heck of a nice bunch of girls and full of pep and fun. It's nice to be able to talk to some feminine company that speaks your own language.

On the other hand, a Red Cross worker noted:

Too many GI's get out of hand and then wonder why the Wacs won't go out with them. There are about 10 percent of the GI's that spoil things for the other 90 percent.

From the viewpoint of the War Department, the most alarming thing about soldier opinion in the North African theater was its effect on recruiting. The theater, like others not surrounded by the American public, never displayed a highly developed sense of those public relations measures that might have counteracted the soldier comment and reassured the women's families. Thus, in the early days it failed to take any positive countermeasures, although as early as February and March of 1943 some American foreign correspondents attempted to do so, notably John Lardner, Inez Robb, and Ernie Pyle. 42

Although the first overseas Waacs were the Corps' greatest potential recruiting publicity asset, few stories or pictures came back. Recognizing that such attention could not be afforded by a combat theater for a tiny minority, Director Hobby attempted to stem the flood of bad publicity by sending a Waac photographer and a writer on temporary duty to get favorable stories. These could be given little assistance in the way of Signal supplies, laboratory facilities, or transportation, since the problem of winning the campaign was immediate and that of recruiting Waacs was remote. The two officers nevertheless managed to secure much favorable comment in various news sources, and to send back pictures of Waacs with General Eisenhower, Maj. Gen. James H. Doolittle, Lt. Gen. Carl Spaatz, and Gen. Henri H. Giraud, and with Spahis in a colorful review.43

Possibly the only other theater problem in WAC employment stemmed from the lack of a firm policy on officer-enlisted relationships. General Eisenhower and General Hughes, in setting the first policy, were of the opinion that no restrictions should be placed on social engagements. Any other policy appeared difficult to enforce because of the presence at Allied Forces headquarters of large numbers of Allied officers and American naval officers, whose services permitted off-duty social association of officers and enlisted personnel. After her arrival, Major Boyce concurred, provided that officers did not date enlisted women who worked for them, thus avoiding the danger of favoritism in promotion. When General Devers took command, he reversed this policy and, over the objection of Major Boyce, directed that both Wacs and nurses observe military customs in selecting their off-duty escorts. Exceptions were made only for relatives and fiancÚs, who had to carry a letter to prove their status.44

[374]

GEN. HENRI H. GIRAUD REVIEWING WAACS in a colorful ceremony in North Africa.

Neither system worked perfectly. Mixed dating in itself caused no difficulty, so long as women did not date their supervisors, except in a few instances in which officers brought enlisted women to their clubs against the wishes of other officers who did not wish to associate with them. Enlisted men were bitterly jealous when officers monopolized the Wacs, but when the Devers ruling restricted enlisted women to dating enlisted men, the unfavorable comments continued and worse problems arose. Major Boyce asked that British and Navy officers be made subject to the ruling, but this proved impossible, and unfortunate public disturbances resulted when military police arrested enlisted Wacs escorted by British or Navy officers.

WAC commanding officers also reported difficulty with Army officers who ignored the rule and then attempted to prevent punishment of enlisted women whom they had dated. WAC commanders were loath to enforce the ruling when officer escorts were not likewise punished, but were allowed no choice under the regulation. Violations were flagrant, and commanders feared that respect for all

[375]

discipline was being damaged. It was attempted to allow some latitude by issuing letters of authorization for engaged couples, but when informed that notices of engagement would be mailed to hometown papers, all but two such couples withdrew their requests for authorization.

In as much as over half of the enlisted women in the theater were eligible for officer candidate school, it was impossible to hope that "natural social level" would cause them to prefer enlisted men. Only the Fifth Army experienced little difficulty, because it was possible to maintain one policy in this command.

No solution was ever found to the problem, which enlisted women frequently cited as the reason for their desire to leave the Army as soon as eligible for discharge. Upon losing an excellent secretary, General White discovered that her departure was due entirely to one incident in the theater, in which she had been arrested for dining in public with her husband, an officer.45

Marriage was not forbidden, and in addition to the Wacs who married officers there were a number of the theater's 4,000 nurses who had married enlisted men. Theater authorities were shortly obliged to be realistic about the situation. Finally, hotels were set aside to which officers and enlisted men might take their wives, and a wife was authorized to take the status of her husband when accompanied by him to hotels, messes, and clubs. However, WAC weddings were not frequent; only about 135 had occurred by the end of the war.46

Wacs in North Africa and Italy considered themselves particularly blessed in the relative scarcity of American civilian employees, who in many other theaters occupied the best jobs. In the few cases where civilian women were employed in this area, the WAC staff director succeeded in pulling Wacs out of the offices concerned, so that conflicts were avoided, and, said Colonel Coleman, "We also successfully ran the OSS civilian women out of the WAC off-duty dress." It was not until the virtual end of hostilities that good enlisted jobs began to be taken over by that phenomenon which always annoyed Wacs irrationally: numbers of civilian women, complete with officers' privileges, fur coats, and duly authorized WAC uniforms.

In addition to the few civilian women employees of the Army, there were other women's groups in abundance-civilian groups such as the USO and the Red Cross, and military groups such as the British ATS and the French "WAC." Of these, the British ATS were the most numerous. Some months after the arrival of the first Waacs, and especially when the theater's Supreme Allied Commander was British, British women in small numbers began to arrive. In general they were housed and fed with the Wacs and worked with the British sections of the various headquarters. The British women proved most generous in sharing their recreational facilities with the Wacs, and all services mingled companionably for tea and other occasions.

In the Fifth Army two groups of ATS women lived and ate with the Wacs. The British women were pleased with the American mess and, said Captain Foster, "it was a pleasure to have them." As much

[376]

could not be said for certain U SO women sometimes billeted with the Fifth Army Wacs, since they habitually managed to be absent at moving time, leaving their tents for the Wacs to take down. Also living with the Fifth Army Wacs were the chief nurse, Red Cross women, and several French women officers. In general Wacs had only praise for the French women's corps, which, after a confused start on ambiguous status, achieved military standing and discipline and whose ambulance drivers were often sent farther forward than the women of any other service.

As for the American Red Cross, personal relations usually depended on the individual; as a group, it appeared to WAC commanders that "there was no place in their program for us." The older British services, on the other hand, had by this time made provision for women in their recreational services. When the American Red Cross failed to provide for the Wacs, the British YWCA set up a series of rest camps in Italy, and General Sir Harold R. L. G. Alexander backed an Allied Women's Club in Caserta. All of these served as many Wacs as ATS, and made it possible for the Wacs to have recreation and three-day passes comparable to those which American services provided for men only. In general, WAC authorities noted that "American agencies were not too well set up to do anything as far as women were concerned, and more often the Wacs had to take care of them.47

For a time it was feared that the Wacs would have to take over supervision of some 500 members of the German women's forces captured in the area. The uncertain status of these women, which might or might not have been that of civilians, roused some doubts in the minds of WAC authorities as to the result if the situation had been reversed. Had German captors been forced to decide WAC status, there appeared some likelihood that Wacs would have been considered civilians through confusion with the numerous civilian women in the OSS, USO, and other groups, all of whom wore the WAC uniform.

As the end of the war approached, WAC advisers became increasingly concerned that in wartime there was no limit to the overseas tour of duty of administrative troops. WAC company commanders noted that there were a few women in every company who became physically or emotionally unfitted for efficient overseas service but who could not be returned, for lack of any authority, until totally disabled.

Colonel Coleman felt that for certain types of work, particularly in the Signal Corps, personnel should be able to look forward to relief at a definite time, and that it would in the final analysis be cheaper to return a good worker while he or she was still capable of rehabilitation and continued service in the United States. She advised theater commanders, "Good service should not be permitted to end in hospitalization if it is possible to avoid it."

It was also Colonel Coleman's opinion that women, if left overseas past the proper time for return, were affected spiritually, not by war and death so much as by long residence in war-disrupted countries where the standards of native life were low and heartbreaking destruction was widespread. Under such circumstances, WAC commanders noted that

[377]

"women gradually hit a place where they have to live on the surface," and a certain temperamental change, of which they were often unaware, appeared to have made them less vulnerable to the sight of others' suffering. For this reason, even when women's health and efficiency were untouched, Colonel Coleman concluded that it would be better, if replacements and shipping were available, to limit an overseas tour to eighteen months.48

When rotation to the United States was finally authorized by the War Department, it was clear that Wacs would not be eligible in competition with men who had much longer service, and in fact most women felt that return would be improper under the circumstances.

At Director Hobby's request, the War Department late in 1944 added a microscopic quota for Wacs and nurses, enough to assure return of emergency cases. Even when Wacs became eligible under regular rules, there was no immediate relief. The theater decided that directives on rotation did not oblige it to return Wacs until a "suitable replacement" was available, and that men even in the same skill were not suitable replacements for women. The theater's new G-1, General White, commented:

I contend emphatically that you cannot cut us off from WAC replacements on the grounds that the theater is overstrength. That is like saying you won't give us any more shoes because we have too many caps.

Eventually the theater was obliged to permit a few Wacs to be returned without replacements, since the War Department decided that these were more badly needed in more active theaters.49

When actual demobilization began, some 80 percent of the women were found to be eligible for discharge under the point system. In spite of some attempts to persuade them to sign up for longer service, some four fifths of eligibles indicated that they wished to be discharged. Many were retained as long as the "military necessity" clause permitted, until after the defeat of Japan, when the War Department directed return of remaining overseas Wacs. By the end of 1945, all enlisted Wacs were out of the Mediterranean theater.50

The Wacs' eagerness to depart indicated, by all evidence, merely a desire for discharge and no condemnation of theater employment as compared to that in the United States. When rotation first began, women who had returned to the United States wrote back comparisons highly favorable to the theater. Accustomed to being treated as essential employees, they found civilians in the best jobs in the zone of the interior, and the civilian population scarcely as respectful as that of occupied areas. Army barracks, even with heating and laundry facilities, were not as comfortable as the apartments and hotels that the Mediterranean theater had provided; neither were there civilians or prisoners to relieve the troops of kitchen police and fatigue duty. Upon receipt of such reports, an overwhelming majority of 95 percent of the remaining women in the theater stated that they preferred to stay overseas until eligible for discharge, rather than return

[378]

to face the hardships of life in the United States. When, upon the cessation of hostilities, a sizable number of individuals on temporary duty were obliged to remain for permanent duty in the United States, their protests were audible in Italy.51

Final comments of both Army and WAC authorities indicated that the theater's WAC experiment had been a successful one. The first theater commander, General Eisenhower, stated of the women:

The WAC in Africa has proved that women can render definite contributions to the winning of the war, and that their capabilities in this regard extend to an actual theater of operations .... In some cases one Wac has been able-because of her expert training-to perform tasks that previously required the assignment of two men. The smartness, neatness, and esprit constantly exhibited has been exemplary . . . their general health and well-being have certainly been equal to that of our best enlisted units.52

The Air Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, Lt. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, added:

As a result of my observation of the WAC personnel to date, I am thoroughly convinced that it should be retained in the after-the-war peacetime Army. I believe it is an indispensable service to our Army in the present emergency. There are innumerable tasks which I have observed WAC personnel performing in the Air Forces with remarkable efficiency . . . . They have a capacity for many specialized duties essential to the Air Forces to a greater extent perhaps than any other Air Force soldier.53

General Clark of the Fifth Army called to tell the Director that he wanted to take his headquarters platoon into Austria with him: "They've plenty of points but I have to have them.54 Col. Westray Battle Boyce, visiting the areas as second Director WAC, after the end of the war, noted that morale was good and the women well adjusted, with adequate provision by the theater for their welfare.55

[379]

Page Created August 23 2002