CHAPTER XIV

Preparing for D-day Landings

By early spring 1944 tactical planning for the most ambitious amphibious operation ever attempted was well under way. OVERLORD represented the fruits of two years of strategic thought, argument, experiment, and improvisation and included compromises reflecting American and British aims. The beaches at Normandy offered the best combination of advantages as a foothold from which the Allies could direct a blow at the Third Reich from the West.

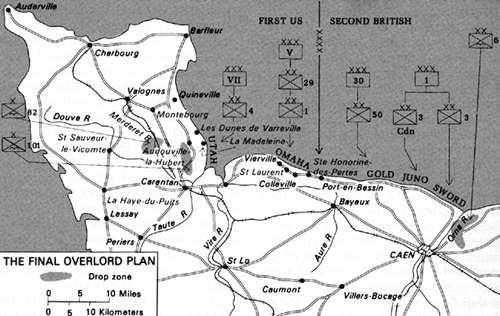

After 1 February 1944, the general concept of an invasion of the Continent in 1944 went by the name OVERLORD. (The increasingly detailed American field army planning-proceeding under tight security at First U.S. Army headquarters-was code named NEPTUNE.) In its final form OVERLORD called for landing two field armies abreast in the Bay of the Seine west of the Orne River, a water barrier that was a suitable anchor for the left flank of the operation. While the British Second Army occupied the easternmost of the chosen landing areas on the left and took the key town of Caen, two corps of the American First Army under Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley were simultaneously to assault two beaches west of the town of Port-en-Bessin. Once ashore the American forces were to swing west and north to clear the Cotentin peninsula by D plus 15, gaining the prize of Cherbourg with its harbor for invasion supply.1

The American Beaches

Invasion planners studied carefully the size, location, gradients, and terrain features of the American OMAHA and UTAH beaches. Within easy reach of the tactical fighter airfields in England, they lay separated from each other by the mouths of the Vire and the Douve rivers. The current in the river delta area where the two streams emptied into the sea deposited silt to form reefs offshore, making landings in the immediate neighborhood infeasible. Protected from westerly Channel swells by the Cotentin peninsula, the waters off OMAHA and UTAH normally had waves up to three feet in the late spring. The six-fathom line ran close enough to shore to allow deep-draft attack transports to unload reasonably near the beaches and naval vessels to bring their guns closer to their targets. Both beaches had a very shallow gradient and tides that receded so rapidly

[299]

that a boat beached for even a few moments at ebb stuck fast until the next incoming water. The tidal range of eighteen feet uncovered a 300-yard flat at low tide. An invasion attempt at low tide would thus force the infantry to walk 300 yards under enemy fire across the undulating tidal flat, crisscrossed with runners and ponds two to four feet deep. (Map 15)

The assault objective of V Corps' 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions was the smaller OMAHA Beach, a gentle, 7,000-yard curve of sand. An eight-foot bank of coarse shingle marked the seaward edge of the western part of the beach. The shingle offered some meager cover to an infantryman but barred passage to wheeled vehicles. Back of the beach, and some two hundred yards from the shingle line at the center, a line of grass-covered bluffs rose dramatically 100 to 170 feet. At either end the bluffs ran down to merge with the rocky headlands that enclosed OMAHA and made the flanking coastline impractical for amphibious landings of any consequence. A bathing resort before the war, the area was not thickly populated, but four farming settlements were nestled 500 to 1,000 yards inland on the bluffs above the beaches. A single main road, part of a predominantly east-west network, roughly paralleled the coast from Vierville-sur-Mer at the western reaches of OMAHA through St. Laurent-sur-Mer, Colleville-sur-Mer, and finally Ste. Honorine-des-Pertes before passing into the British Second Army sector behind the beaches to the east. Access to the beaches from the farming communities was through four large and several smaller gullies or draws. Through one of these, dropping from Vierville to the water, a gravel secondary road ran to the beach and turned to the east. It continued beside a six- to twelve-foot timber and masonry seawall to Les Moulins, a small village directly on the sea in the draw in front of St. Laurent. From there back to St. Laurent and in the draw from Colleville to the water, roads were no more than cart tracks or sandy paths. A line of bathing cabanas and summer cottages had nestled beneath the bluffs west of Les Moulins in an area known as Hamel-au-Pretre, but the Germans had razed most of them as they erected their beach defenses and cleared fields of fire. There were few signs of habitation east of Les Moulins, and the foot paths at that end of the beach ran out altogether in the marsh grass sand.2

The NEPTUNE planners divided OMAHA Beach into eight contiguous landing zones. From its far western end to the draw before Vierville, Charlie Beach was the target of a provisional Ranger force. Next were the main assault areas, Dog and Easy beaches. Dog Green, 970 yards long, Dog White, 700 yards, and Dog Red, 480 yards, stretched from the Vierville draw to the one at Les Moulins. Easy Green began there, running 830 yards east. Easy Red, 1,850 yards, straddled the draw going up to Colleville, and Fox Red, 3,015 yards at the far left of the beach, had a smaller draw on its right-hand boundary. The five draws, vital beach exits, were simply named: the Vierville exit became D-1, the one at Les Moulins leading to St. Laurent, D-3; E-1 lay in the middle of Easy Red leading up between St. Laurent and Colleville; the Colleville draw off

[300]

MAP 15

Fox Green became E-3, and the smaller one leading off Fox Red, F-1.

After a 45-minute air and naval bombardment on D-day, the reinforced 116th Regimental Combat Team, assigned to the 29th Infantry Division (but attached to the 1st Division for the assault), was to land on Dog Green, Dog White, Dog Red, and Easy Green, preceded moments earlier by four companies of the 741st Tank Battalion serving as assault artillery. The 16th Regimental Combat Team, 1st Infantry Division, was to touch down on Easy Red and Fox Green, with a battalion landing team on each beach. The assault units were to push through the German defense ,along the beaches, especially in the draws leading inland, by the time the landing was three hours old. Reinforced with additional forces coming ashore, V Corps would then consolidate an area of hedgerow country bounded on the south by the line of the Aure River by the end of D-day.

German defenses in the area from Caen west, taking in the Cotentin and Brittany peninsulas, fell under the German Seventh Army. In the OMAHA area the counterinvasion force on the coast consisted of two divisions, the 716th, a static or defense division having no equivalent in the American Army, and the 352d, a conventional infantry division capable of counterattack and rapid movement. In general the Germans concentrated on emplacing a coastal shield, following Field Marshal Erwin Rommel's strategy of defeating an invasion at the water's edge. The demands

[301]

of the war in the east denied the vaunted German Atlantic Wall the concrete, the mines, and the trained men Rommel wanted, but the beach defenses, though incomplete, were formidable enough for any assault force.3

Since the Germans considered a low-tide landing impossible because of the exposed area in front of their guns, they littered the tidal flat with obstacles to catch landing craft coming ashore at high tide. About 250 yards from the shingle line stood a row of complicated structures called Element C, nicknamed Belgian gates because they resembled the ornamental ironwork of a European chateau. Festooned with waterproofed mines, they covered either end of the beach but not its center. Behind them were irregular rows of single upright or slightly canted steel stakes, V-shaped channeled rails that could tear out the bottom of a landing craft; roughly every third one had a Teller mine fixed atop it. The Germans had emplaced and mined logs and built shallow, mined ramps with one upright wooden pole supported by two longer trailing legs. Closest to the high-water mark was a row of hedgehogs, constructed by bolting or welding together three or more channeled rails at their centers so as to project impaling spokes in three directions. The tidal flat contained no buried mines, since the sea water rapidly made them ineffective.4

On shore, twelve fixed gun emplacements of the German coastal defense net between the Vire River and Port-en-Bessin could fire directly on the beach. The defenders concentrated their pillboxes at the all-important beach exits and supplemented the artillery pieces with automatic-weapons and small-arms firing pits. They dug antitank ditches ten feet deep and thirty feet wide across the mouths of the draws. One pillbox, set in the embankment of the Vierville draw, D-1, could enfilade the beach eastward as far as Les Moulins. On the landward side of the shingle bank and along the seawall they erected concertina barbed wire and laced the sand with their standard Schu and Teller mines. From the trench system on the bluffs above they could also activate an assortment of explosive devices, using old French naval shells and stone fougasses (TNT charges that blew out rock fragments) against any attackers scaling the heights.

In January 1944 the COSSAC staff decided to strengthen the American attempt to seize Cherbourg by revising OVERLORD to bring another corps ashore closer to that port. Because of the river lines and the marshy terrain to the west of OMAHA, V Corps ran the risk of being stopped around the town of Carentan before wheeling into the Cotentin peninsula. The revised plan assigned the VII Corps, with the 4th Infantry Division in the assault, to the second American D-day beach.

A straight 9,000-yard stretch of rather characterless coastline, UTAH lay on a north-south axis west of the mouth of the Douve and to the east of the town of Ste. Mere-Eglise. A masonry seawall eight feet high ran the length of the beach, protecting the dunes behind it from storms. At intermittent points along this barrier sand had piled up to make ramps as high as the wall itself; only a wire fence atop the wall marked its presence. German defenders had

[302]

flooded the low-lying pastureland between the beach and Ste. Mere-Eglise to a depth of four feet. A series of east-west causeways carried small roads across the flood; each ended at a break in the seawall which normally gave access to the beach, but which the Germans had also blocked to contain an assault force from the sea.

The beach assault area lay between two hamlets, La Madeleine on the south and Les Dunes de Varreville on the north. The southerly Uncle Red Beach, 1,000 yards long, straddled a causeway road named Exit No. 3; it led directly to the village of Audouville-la-Hubert, due east of Ste. Mere-Eglise and three miles behind the beach. Tare Green Beach, occupying the 1,000 yards to the right of Uncle Red, had few distinguishing natural features. At UTAH, the 8th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, was to go ashore two battalion landing teams abreast, closely followed by the 70th Tank Battalion as artillery support.5

NEPTUNE also called for a parachute and glider assault into the area behind UTAH. TO cut the Cotentin peninsula at its base, COSSAC planners originally scheduled airdrops south and east of Ste. Mere-Eglise and farther west in the vicinity of St. Sauveur-le-Vicomte. But when the 91st Infantry Division reinforced the peninsula in May, the First Army staff had to consider a less ambitious airborne undertaking. The 82d Airborne Division would be dropped astride the Merderet River, a tributary of the Douve running two miles west of Ste. Mere-Eglise, and the 101st Airborne Division in the area south of the town early on D-day before the 4th Infantry Division landed at UTAH. Glider trains would bring in reinforcements and heavier weapons to consolidate a perimeter enclosing a section of the Carentan-Cherbourg highway and at least the inland portions of the causeways that would serve as beach exits.6

A lack of high ground made the German defenses at UTAH somewhat less imposing than at OMAHA. The defenders relied heavily on the inundated lowlands behind the beach to channel an attack and on a series of small infantry strongpoints to pin down a larger force trying to leave the beach over the causeways. Consistent with their strategic conception, the German works were well forward. Two German divisions, the 709th Infantry, manned with eastern Europeans, mainly Georgians, and the 243d Infants, had constructed numerous resistance points along the high-water mark. On the tidal flat they had placed the obstacles encountered at OMAHA and another antitank device called a tetrahedron, a small pyramid of steel or concrete. Barbed-wire entanglements and minefields, covered by rifle, automatic, and mortar fire from the infantry trenches, began at the water's edge. Concrete pillboxes, some with tank turrets set into them, swept the beaches with arcs of fire. The villages at the edges of UTAH were converted into fortified areas commanding both the beach and sectors of the inundated land to the rear. Just right of center on Tare Green, the Germans dug a deep antitank ditch to hinder vehicles and tanks coming in from the sea. At UTAH the enemy also introduced the Goliath, a miniature, radio-controlled tank loaded with explosives

[303]

and designed to engage incoming landing craft and armor. The arrival in late May of the 91st Division, with a battalion of tanks, gave considerable depth to the defense between Carentan and Valognes, but the defenders of the beaches themselves could hardly maneuver, since their own flooding confined them to positions in the narrow coastal strip where there was little room for regrouping and counterattack.

Despite the serious German aggregation of firepower along the coastline, NEPTUNE planners in the months before the invasion worried most about obstacles. In early 1944 as aerial photographs of the German-held coastal areas showed a proliferation of obstacles on the invasion beaches, the Allies grew more and more alarmed. A month before D-day, General Eisenhower listed the devices as among the "worst problems of these days."7

Beach Obstacle Teams

In deriving plans and stratagems to overcome the obstacle problem the Allies drew on their experience, though the new situation exceeded in size and complexity anything they had previously encountered. In the ill-fated Dieppe raid of August 1942, British and Canadian forces had met concrete walls and blocks set with steel spikes designed to impale landing craft. The British had then established an Underwater Obstacle Training Center, but its elaborate training courses were chiefly geared for Mediterranean beach landings. The British experience prompted the chief of engineers to propose a similar Army center in the United States, but in the spring of 1943 the Navy took over all amphibious training. The engineers then selected a site for a beach obstacle course close to the Navy's Amphibious Training Base at Fort Pierce, Florida.

The course began in July 1943, and throughout the fall a company of combat engineers conducted experiments in coordination with the Navy. The tests indicated that the obstacles that remained after a thorough bombing of the beaches could probably be blown to bits by such devices as the "Apex," a remote-controlled drone boat, and the "Ready Fox," an explosive-laden pipe that could be towed into the area and sunk. The engineers could also destroy obstacles with rocket fire, preferably from rocket launchers mounted on a tank; at low tide heavy mechanized equipment such as the tankdozer could push most obstacles out of the way.8

Although the engineers were testing these methods, ETOUSA planners hoped that such removal work would prove unnecessary, for during 1943 reconnaissance had uncovered no obstacles along the Normandy coast. Indeed, an early engineer plan assumed that there would be no obstacles or that, if the Germans attempted to install any at the last minute, naval gunfire and aerial bombardment would take care of them. As a last resort, alternative beaches might be chosen.9

This optimism waned in late January 1944, when aerial reconnaissance disclosed hedgehogs on the beach at Quineville, just north of the UTAH section of

[304]

the Cotentin coast. Disturbed at this turn of events, General Eisenhower sent Lt. Col. Arthur H. Davidson, Jr., of General Moore s staff and Lt. Col. John T. O'Neill, commander of V Corps 112th Engineer Combat Battalion, to attend an obstacle demonstration at Fort Pierce in Florida between 9 and 11 February.10

Returning to the theater about two weeks later, Davidson and O'Neill found D-day planners studying aerial photographs that showed the Germans were planting obstacles on the tidal flats below the high-water mark-a great hazard to landing craft. Subsequent photographs revealed that obstacles, usually planted in three rows, were multiplying rapidly not only in the UTAH area but also, beginning late in March, at OMAHA. Planners assumed that they were all strengthened with barbed wire and mines. That assumption proved correct on 23 April when an Allied bomb intended for a coastal battery fell on the beach, producing fourteen secondary explosions. Aerial photographs showed the obstacles proliferating on all beaches right up to D-day.11

Detailed planning for breaching the obstacles on D-day began in the United Kingdom in mid-March 1944 when General Bradley directed V and VII Corps to submit clearing plans for OMAHA and UTAH beaches by 1 April. Because time was short, Bradley told planners to depend on only the troops, materials, equipment, and techniques then available in the theater.

Available troops included the corps combat engineers, engineer special brigades, and sixteen naval combat demolition units (NCDUs). Each NCDU consisted of five enlisted men and an officer-the capacity of the black rubber boats NCDUs used in their work. They had been trained to paddle to shallow water and then go overboard, wading to shore and dragging the explosive-filled boat behind them. The first unit, members of the earliest Fort Pierce graduating class, arrived in the theater at the end of October 1943. By March 1944 all sixteen units had arrived and had been assigned to naval beach battalions training at Salcombe, Swansea, and Fowey. The demolition units had little idea of precisely what their role on D-day would be. They had no training aids other than those they could improvise, nor were they told until mid-April (because of strict security regulations) the type of obstacles being discovered along the Normandy beaches.12

On 1 April 1944, V Corps submitted to First Army a plan for breaching obstacles, prepared jointly with the XI Amphibious Force, US Navy. The plan recommended that an engineer group consisting of two engineer combat battalions and twenty NCDUs be organized and specially trained for the OMAHA assault; VII Corps submitted a similar smaller scale plan for UTAH.13

[305]

The V Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, was disturbed to learn on 9 April that First Army still had adopted no definite obstacle plan and that training had barely started. That same day First Army asked V Corps to send two engineer companies and a tank company with tankdozers to the Assault Training Center at Woolacombe. The 299th Engineer Combat Battalion, with personnel specially trained at Fort Pierce, was to arrive in the United Kingdom on 16 April, but only about one-third of the battalion had been trained in the removal of underwater obstacles. Another cause for worry was a scarcity of tankdozer blades. To speed the adoption of a specific plan and undertake vital training, Gerow enlisted the support of Brig. Gen. William B. Kean, First Army chief of staff. Kean had to admit that "this whole subject had been worked out far too late." Gerow sent two engineer companies with four tankdozers and six NCDUs to begin training at Woolacombe on 12 April.14

Army and Navy representatives formulated detailed plans beginning 15 April, when for the first time demolition men obtained precise information on the tidal-flat obstacles they could expect to encounter. Because of the number and density of the obstacles, the conferees decided to attack them "dry shod," ahead of the incoming tide. This decision helped fix the invasion date-only on 5, 6, or 7 June would the engineers have enough daylight after H-hour to destroy the obstacles before the onrushing Channel tide covered them. The decision to attack dry shod also obviated the need for Apex boats- luckily, for the freighters bringing them from the United States did not arrive in England until mid-May, too late to prepare the boats for use. The first Reddy Foxes, which might have helped, came in the same shipment and had to be put in storage along with the Apexes because there was no time to train men in their use. Under such circumstances, the most practicable method of breaching the obstacles seemed that of placing explosive charges by hand, although NCDU officers continued to warn that this course would be possible only if enemy fire could be neutralized.15

On OMAHA, gaps fifty yards wide were to be blown through the obstacles, two in each beach subsector. The broader Easy Red would be breached in six places. Combined Army-Navy boat teams of thirty-five to forty men carried in LCMs were to undertake the task. The sailors were to destroy the seaward obstacles, the soldiers to handle those landward and to clear mines from the tidal flat. First on the scene would be the assault gapping team (one to each gap), composed of twenty-seven men from an Army engineer combat battalion (including one officer and one medic) and an NCDU augmented to thirteen men by the attachment of five Army engineers to help with demolitions and two seamen to handle the explosives and tend the rubber boats.

The assault teams were to be followed by eight support teams, one to every

[306]

two assault teams, of about the same composition. Two command boats completed the flotilla. Command was to be an Army responsibility because the obstacles would presumably be dry at the time of clearing operations. Each assault team was to be supported by a tankdozer to clear obstacles. All boats were to carry some 1,000 pounds of explosives, demolition accessories, mine detectors, and mine gap markers. The command boats were to carry a ton of extra explosive.16

At UTAH Beach eight fifty-yard gaps were planned, four in each of the two landing sectors. Boat teams were to be employed in a somewhat different manner. Twelve NCDUs, each consisting of an officer and fifteen men (including five Army engineers) carried in twelve LCVPs, were to attack the seaward band of obstacles. Simultaneously, eight Army demolition teams, each consisting of an officer and twenty-five enlisted men carried in eight LCMs, were to attack the landward obstacles. Four Army reserve teams of the same size, also in LCMs, were to follow the eight leading Army teams shoreward. As at OMAHA, the attackers would rely heavily on standard engineer explosives and tankdozers, and the Army would have command responsibility for obstacle-clearing operations.

On 30 April, V Corps organized the V Corps Provisional Engineer Group for the OMAHA assault. Under Colonel O'Neill, formerly commander of the 112th Engineer Combat Battalion, the provisional group consisted of the 146th Engineer Combat Battalion, the 299th Engineer Combat Battalion (less one company), and twenty-one NCDUs. Ultimately, 150 demolition-trained men of the Ed Infantry Division joined the provisional group to bring its strength to 1,050. Upon its attachment to the 1st Infantry Division for the assault, the provisional group was redesignated the Special Engineer Task Force.

For UTAH obstacle-clearing operations VII Corps organized the Beach Obstacle Demolition Party under Maj. Herschel E. Linn, commander of the 237th Engineer Combat Battalion. Smaller than the OMAHA organization, the UTAH group consisted mainly of one company of the 237th Engineer Combat Battalion, another from the 299th Engineer Combat Battalion, and twelve NCDUs. To supply the remaining naval support to the UTAH and OMAHA forces, additional NCDUs arrived from the United States on 6 May.17

On 27 April, when direction of training for OMAHA passed from First Army to V Corps control, two engineer combat battalions (less one company) and twenty-one NCDUs went to Woolacombe for training, but not until 1 May were aerial photographs of OMAHA available for study. Obstacles of the kind shown in detail in low-level photographs were then erected at Woolacombe, and though training aids were lacking the troops practiced debarking from landing craft with explosives and equipment and experimented with waterproofing methods, tankdozer employment, barbed-wire breaching, and other techniques.18

An NCDU officer, Lt. (jg.) Carl P. Hagensen, developed a method for flattening the big Belgian gate obstacles

[307]

with the least danger to troops and landing craft from steel fragments and shards. Tests indicated that sixteen "Hagensen packs"-small sausage-like waterproof canvas bags filled with two pounds of a new plastic explosive, Composition C-2, and fitted with a hook at one end and a cord at the other-could be quickly attached to the gates' steel girders. When a connecting "ring main" of primacord exploded the packs simultaneously, the gate fell over.

Ten thousand Hagensen packs-with canvas bags sewn by sailmakers in lofts throughout England-were produced during an eleventh-hour roundup of gear and equipment that began when the brief training period ended in mid-May. Some improvisation of supplies proved possible. For example, mortar ammunition bags could hold waterproof fuses and the twenty Hagensen packs each demolition man would carry. Nevertheless, procurement problems were considerable. The OMAHA obstacle teams alone required twenty-eight tons of explosives and seventy-five miles of primacord. Tankdozers, D-8 armored dozers, special minefield gap markers, special towing cables, and a multitude of miscellaneous engineer items also had to be procured. The matériel was found and assembled in a remarkably short ten days.

There was also little time for training the demolition teams. Joint training for most of the Army-Navy teams started late and for many units lasted no more than two weeks. On 15 May the NCDUs moved to Salcombe, a Navy amphibious training center, and spent their time preparing Hagensen packs and obtaining final items of gear. Not until the end of May did they rejoin the Army demolition teams, which since mid-May had been waiting for D-day in their marshaling areas farther east.19

In addition to the obstacle problem there remained a second engineer responsibility, equally central to the success of the operation: the organization of the supply moving on an unprecedented scale across a complex of invasion beaches. First Army planners turned to the proven engineer special brigades, but then devised new command arrangements to accommodate the sheer mass of the invasion traffic.

The Engineer Special Brigades

At this stage of the war, the engineer special brigades in the European theater were exclusively shore units since the Navy had taken their watercraft. The brigades now had additional service units to accomplish the enormous cargo transfers necessary for assault operations. Basic units included three engineer combat battalions, a medical battalion, a joint assault signal company, a military police (MP) company, a DUKW battalion, an ordnance battalion, and various quartermaster troops. Extra equipment included power cranes, angledozers, motorized road graders, tractors, and six-ton Athey trailers.20

[308]

The 1st Engineer Special Brigade, which had reached a strength of some 20,000 men in Sicily, moved to England in December 1943 with only a nucleus of its old organization-3,346 men, including a medical battalion, a quartermaster DUKW battalion, a signal company, and some ordnance troops. Unlike the other two engineer brigades to be employed in NEPTUNE, the 1st Engineer Special Brigade had an experienced unit in the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment, which had served in the Northwest Africa, Sicily, and Salerno landings. The 1st Engineer Special Brigade expanded in England to some 15,000 troops by D-day.21

The 5th Engineer Special Brigade was organized in the United Kingdom on 12 November 1943 from the 1119th Engineer Combat Group with three attached engineer combat battalions (the 37th, 336th, and 348th). The 6th Engineer Special Brigade was formed in January 1944 from the 1116th Engineer Combat Group (147th, 149th, and 203d Engineer Combat Battalions). The staff of the 1116th brought with it a plan, conceived during training in the United States, to employ battalion beach groups, each composed of an engineer combat battalion with attached troops. This concept was similar to that the 1st Engineer Special Brigade had developed in the Mediterranean.

The 6th Engineer Special Brigade planned to deploy two battalion beach groups on the beach, with another engineer combat battalion assuming responsibility for most of the work inland. The beach groups were to unload cargo from ships and move it to dumps. They were also responsible for roads, mine clearance, and similar engineer work; reinforced quartermaster and ordnance battalions would operate the dumps. In the assault phase all operations of the 6th Engineer Special Brigade were to be controlled by the reinforced 149th Engineer Combat Battalion Beach Group. As operations progressed into the beach maintenance phase, the various battalions were to regain control of their elements initially attached to the 149th and to assume responsibility for their operations.22

The 5th Engineer Special Brigade divided itself into three battalion beach groups. Each consisted of an engineer combat battalion, a naval beach company, a quartermaster service company, a DUKW company, a medical collection company, a quartermaster railhead company, a platoon of a quartermaster gasoline supply company, a platoon of an ordnance ammunition company, a platoon of an ordnance medium automotive maintenance company, military police, chemical decontamination and joint assault signal platoons, and two auxiliary surgical teams.23

Headquarters, First Army, the American tactical planning agency, outlined the responsibilities of the engineer special brigades in an operations memorandum on 13 February 1944. Each engineer battalion beach group would support the assault of a regimental combat team and each engineer company groupment the assault landing of an infantry battalion landing team. First Army also authorized the grouping of

[309]

the 5th and 6th Engineer Special Brigades under a headquarters known as the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group. It soon became evident that the two brigades would not be sufficient to handle the OMAHA operation, which, besides the beaches, included an artificial port and the minor ports of Grandcamp-les-Bains and Isiguy. The 11th Port (TC), which had been operating the Bristol Channel ports, then augmented the engineer group with four port battalions, five DUKW companies, three quartermaster service companies, three quartermaster truck companies, an ordnance medium automotive maintenance company, and a utility detachment-more than 8,000 men in all. Earmarked to operate the pierheads and minor ports, the 11th Port required no training in beach operations.

Assault Training and Rehearsals

The combat battalions of both the 5th and 6th Engineer Special Brigades had had amphibious training on the Atlantic coast at Fort Pierce, Florida, the US Navy's Amphibious Training Base. But some units, notably quartermaster units, had had no amphibious training before joining the brigades, and the training the 5th Engineer Special Brigade's combat battalions received in the United States proved "elementary" in the light of the heavy demands soon to be placed upon the units. Brigade units received further training in mine work, Bailey bridge construction, road maintenance, and demolitions upon arrival at Swansea on the south coast of Wales early in November, by early January 1944 they were receiving training in landing operations at nearby Oxwich Beach. The 6th Engineer Special Brigade, stationed at Paignton in Devon, conducted similar exercises at neighboring Goodrington Sands during February.24

The first of a series of major exercises involving assault troops and shore engineers began in early January 1944 at Slapton Sands on the southern coast of England, an area from which some 6,000 persons had been evacuated from eight villages and eighty farms. The exercise, called DUCK I, involved l0,000 troops. The assault forces consisted of the inexperienced 29th Infantry Division of V Corps. To give the division some training with shore engineers, the V Corps commander called on Col. Eugene M. Caffey, commanding officer of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade (stationed at Truro in Cornwall), for support. The brigade had arrived in England from the Mediterranean understrength and with no equipment, but, by scouring England for equipment and borrowing officers and units, Colonel Caffey was able to furnish elements of his brigade for the exercise.

Succeeding exercises, DUCK II and III, were held in February to train elements of the 29th Division and the 1st Engineer Special Brigade that had not participated in DUCK I. The beach at Slapton Sands was ideal for training, since it approximated conditions later found at UTAH. But one purpose of the combined exercise accustoming assault forces to the beach organization tasks that would face them on D-day could not be realized because OVERLORD tactical plans were not firm until late in February. After the 1st Engineer Special Brigade learned it would not be with the 29th Division but with

[310]

INFANTRY TROOPS LEAVE LST DURING EXERCISE FABIUS at Slapton Sands, April 1944.

the 4th, the brigade participated in a series of seven exercises with elements of the 4th Division during the last two weeks of March. The first four practice sessions involved engineer detachments supporting battalion landing teams; the next two involved regimental combat teams. VII Corps conducted the last exercise on a scale approaching DUCK I. Two regimental combat teams trained with a large beach party from the 1st Engineer Special Brigade and extra engineers, parachute troops, and air forces elements.25

Exercise Fox, involving 17,000 troops scheduled to land at OMAHA, took place at Slapton Sands 9-10 March. The 37th Engineer Combat Battalion Beach Group of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade supported the 16th Regimental Combat Team, and the 149th Engineer Battalion Beach Group of the 6th Engineer Special Brigade supported the 116th Regimental Combat Team. This exercise had been delayed so that it could parallel final tactical planning for OVERLORD, and it suffered to some extent from late and hurried preparations as well as the inexperience of the units participating. Neither the mounting nor the beach operations went as well as hoped, but both the engineers and the assault troops learned better

[311]

use of DUKWs and more efficient waterproofing of vehicles.26

The major exercises led to the two great rehearsals for the invasion: TIGER and FABIUS. TIGER, the rehearsal for the UTAH landings, came first. Some 25,000 men including the 4th Infantry Division, airborne troops, and the 1st Engineer Special Brigade participated under the direction of VII Corps. TIGER lasted nine days (22-30 April) with the first six given over to marshaling. Landings in the Slapton Sands area were to begin at 0630 on 28 April.

At 0130 eight LSTs, proceeding westward toward the assault area with the 1st Engineer Special Brigade, troops of the 4th Division, and VII Corps headquarters aboard, were attacked off Portland by enemy craft, presumably German E-boats. Torpedoes sank two LSTs and damaged a third so badly that it had to be towed back to Dartmouth. The German craft machine-gunned the decks of the LSTs and men in the water. LST-531, with 1,026 soldiers and sailors aboard, had only 290 survivors; total US Army casualties were 749 killed and more than 300 wounded. The 1st Engineer Special Brigade, with 413 dead and 16 wounded, suffered heavily in the action. Its 3206th Quartermaster Service Company was virtually wiped out, and the 557th Quartermaster Railhead Company also sustained heavy losses. Both had to be replaced for the invasion.27

Shattered by the disaster, which reduced it to little more than its assault phase elements, the 1st Engineer Special Brigade made a poor showing in TIGER. Observing the landings from an LCI offshore, General Bradley was disturbed. For some "unexplained reason" a full report on the loss of the LSTs, which he came later to consider "one of the major tragedies of the European war," did not reach him, and from the sketchy report he received he concluded that the damage had been slight. Attributing the poor performance of the brigade to a breakdown in command, he suggested to Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, commanding VII Corps, that a new commander be assigned. Collins gave the job to Brig. Gen. James E. Wharton. Thus by a combination of misfortune and misunderstanding, Col. Eugene M. Caffey who had led the 1st Engineer Special Brigade in the Sicily landings, was not to lead it on D-day in Normandy.28

FABIUS consisted of six exercises carried out under the direction of 21 Army Group. FABIUS I was the rehearsal for Force O. the 1st Division units that were to assault OMAHA Beach. Approximately 25,000 troops participated in FABIUS I, including three regimental combat teams and various attached service troops. FABIUS II, III, IV, and V were British rehearsals carried out at the same time. FABIUS VI was a marshaling exercise for follow-up Force B (the 29th Division) and the British forces in the buildup. It ran from 3 April to 7 May, with a simulated D-day on 3 May.

Every effort was made to deploy regimental combat teams from the 1st and 29th Divisions plus two Ranger and two tank battalions supported by three engineer combat battalions on the second tide on D-day and 300 tons of supply

[312]

COLONEL CAFFEY (Photograph taken in 1952.)

on D plus 1-including treadway bridging, Sommerfeld track, coir matting, and other material for building and improving beach roads. A number of faults showed up in beach operations, but since D-day was only a month away no drastic revisions could be undertaken. The most important result of the exercise was a change in the landing schedules; elements of the military police company, the brigade headquarters, and the signal company were to land considerably earlier than originally planned. After FABIUS was over, most of the units that had participated went directly to their marshaling areas.

Marshaling the Invasion Force

The primary responsibilities for marshaling engineer personnel, vehicles, and supplies for shipment to Normandy fell to the engineers of Western Base Section (WBS) and especially Southern Base Section (SBS), which had a larger number of marshaling areas. US forces in the initial assault were to embark from points in England west of Poole, and early reinforcements were to load at ports in the Bristol Channel in advance of the operation. Later reinforcements were to move through Southampton, Portland, and Plymouth.

Of the nine major marshaling and embarkation areas in SBS, the British operated one. The British and Americans jointly ran two areas around Southampton; the Americans operated the other six areas. Each marshaling area was to be used to 75 percent of its capacity, with the remaining 25 percent kept in reserve to accommodate troops and vehicles that might not be able to move out because of enemy action, adverse weather, or other circumstance. SBS made available many engineer troops, including general service regiments, camouflage companies, water supply companies, fire-fighting platoons, and various smaller detachments to help operate the marshaling areas.29

In the marshaling areas the first step was to construct necessary additional installations. Because the ports did not have the capacity to load the huge invasion fleet at one time, base section engineers had to build, either within the ports or along riverbanks, concrete

[313]

aprons from existing roads to the water's edge. Known as "hards" (for hardstandings), the aprons had to extend out into the water. They consisted of precast concrete units, called "chocolate bars" because of their scored checkerboard surfaces. Averaging ten inches in thickness, each section measured about 2-by-3-feet, which, laid end to end, formed a rough road. Both sides of the slabs were scored-the top surface to prevent vehicles from slipping, the bottom surface to bite into the beach. The landing craft or landing ships anchored at the foot of the hard or apron, let down their ramps, and took on vehicles and personnel dry shod; no piers or docks were necessary. Because landing craft were of shallow draft, flat-bottomed, and most unstable in rough seas and because the south coast of England was generally unprotected, windswept, and subject to tides that greatly changed water depths, careful reconnaissance and British advice were necessary to locate loading sites or embarkation points in sheltered sections, generally in a port or a river mouth.30

Next came the selection of temporary camp sites near embarkation points. The capacity for out-loading from a certain group of herds determined the size and number of camps located nearby. Each marshaling area had railheads for storing all classes of supplies, and every camp was supposed to maintain a stock of food, along with fast-moving items.

The marshaling areas were of two patterns, large camps that might accommodate as many as 9,000 men and sausage-style camps-fourteen small camps, each with a capacity of 230 men, ranged along five to ten miles of roadway. These small camps provided better dispersal and the possibility of good camouflage, for tentage followed hedgerows. But they required more personnel for efficient operation because some degree of control was lost. Good camouflage practices were not always followed.31

Most of the camps consisted of quarters for 200 enlisted men (often in pyramidal tents), officers' quarters, orderly rooms, supply rooms, cooks' quarters, kitchen, mess halls, and latrines. Special briefing tents with sand tables were also available. Where necessary, engineers erected flattops over open areas used for mess lines.32 In both the Southern and Western Base Sections they also constructed security enclosures and special facilities. Engineers had to maintain and waterproof engineer task force vehicles. Each marshaling camp had either a concrete tank or a dammed stream for testing waterproofing. Roads, railroads, bridges, and dock and port facilities were primarily British responsibilities, and American engineers performed maintenance in these areas only on request or in case of emergency.33

The Western Base Section's task was easier than Southern Base Section's for little new construction was required. Existing troop camps were big enough and close enough to the ports. Camp capacities were increased by billeting eighteen instead of sixteen men in each

[314]

16-by-36-foot hut and by adding an extra man to each seven-man 16-by-16-foot pyramidal tent. Additional tents were also erected with construction materials the Royal Engineers contributed.

Providing the needed accommodations in both Western and Southern Base Sections entailed much more than acquiring buildings and erecting tents. An acute shortage of base section engineer operating personnel which arose in the spring of 1944 promised to become worse once the invasion-mounting machinery went into full swing. SOS, ETOUSA, officials recognized the problem as early as February 1944 and saw the need to use field forces to help out. General Lee estimated that at least 15,000 field force troops would be required, along with 46,000 SOS troops who would have to be taken off other work. As a result, ETOUSA permitted an entire armored division to be cannibalized to provide some of the troops needed for housekeeping in the marshaling areas. Of the total, 4,500 were assigned as cooks, but many of these men were not qualified. General Moore thought the shortage in mess personnel was frequently the weakest part of the engineer phase of marshaling.34

Briefings began in the marshaling areas on 22 May 1944. The Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group's commander, Brig. Gen. William M. Hoge, issued a simple but effective order: "It is my desire that every individual soldier in this command, destined for the far shores be thoroughly instructed as to the general mission and plan of his unit, and what he is to do." The men received instruction in briefing tents containing models of the Normandy beaches, maps, overprints, charts, aerial photographs, and mosaics.35

Battalion beach groups formed from the 5th and 6th Engineer Brigade Groups, the latter initially under the 5th Engineer Special Brigade, were to support the V Corps landings on the 7,000-yard stretch of beach fronting the Vierville-Colleville area. The 5th Engineer Special Brigade was to operate all shore installations in sectors Easy, Fox, and George to the left of the common brigade boundary. The 6th Engineer Special Brigade was to operate those in sectors Charlie, Dog, and Easy to the right of the brigade boundary. Headquarters, Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group, was to assume control of the two brigades as soon as its command post was established ashore. The 1st Division (less the 26th Regimental Combat Team), with the 29th Division's 116th Regimental Combat Team and other troops attached, made up Force O. the initial assault force. The 29th Division, less the 116th Regimental Combat Team but with the 26th Regimental Combat Team and other troops attached, constituted the immediate follow-up force, Force B.36

Upon landing, engineer special brigade engineers were to relieve divisional engineers on the beaches. Then they were to develop and expand the roadway system and open additional exits and roads within the established beach maintenance area, with the goal

[315]

of having that area fully developed by D plus 3. Initially beach dumps were to be set up about a thousand yards inland; later the brigade group was to consolidate these dumps up to five miles inland. Separate areas were to be set aside for USAAF dumps, troop transit areas, and vehicle transit areas.

The 5th Engineer Special Brigade undertook a number of tasks, some in support of or in coordination with the Navy. The men marked naval hazards near the beach, determined the best landing areas, and then marked the beach limits and debarkation points. They helped remove beach obstacles and developed and operated assault landing beaches. They controlled boat traffic near the beach and directed the landing, retraction, and salvage of craft as well as unloading all craft beaching within their sector. Brigade members also developed beach exits to permit the flow of 120 vehicles an hour by H plus 3, organized and operated initial beach dumps, directed traffic, and maintained a naval pontoon causeway. They operated personnel and vehicle transit areas, set up and operated a POW stockade, kept track of organizations and supplies that landed, and established initial ship-to-shore communications. Finally, they gave first aid to beach casualties before evacuating them to ships.

The general plan called for progressive development of the OMAHA beachhead in three phases. The assault phase would be under company control, the initial dump phase under battalion beach group control, and the beach maintenance dump phase under brigade control. Daring the first two phases at OMAHA Beach, groups of the 5th and 6th Engineer Special Brigades were to support the landings of the 1st Division.

The 37th Engineer Battalion Beach Group (of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade) was to support the 16th Regimental Combat Team; the 149th Beach Group, with the 147th Beach Group attached (both from the 6th Engineer Special Brigade), was to support the 116th Regimental Combat Team; and the 348th Beach Group (of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade) was to support the 18th Regimental Combat Team. The 29th Division's lead regimental combat team, the 26th, was to be supported by the 336th Engineer Combat Battalion Beach Group of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade.

The duties of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade, supporting the assault landings of the 4th Infantry Division of VII Corps on UTAH Beach, were similar to those of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade on OMAHA. Uncle Red Beach on the left and Tare Green Beach on the right were each to be operated by a battalion beach group of the brigade's 531st Engineer Shore Regiment; as soon as a third beach group could land, a third beach, Sugar Red, was to be opened at the right of Tare Green.37

In the briefings before D-day, the engineer special brigades received intelligence information concerning enemy forces, the progressive development of enemy defenses, detailed geographic and hydrographic studies, reports on local resources, and a model of the beach and adjacent areas. Defense overprints provided detailed information about gun positions, minefields, beach obstacles, roadblocks, and antitank

[316]

ditches. An Admiralty Tide Chart prepared at scale 1:7,920 was valuable, as was a 1:5,000 chart-map that the Information Section, Intelligence Division, OCE, published. However, the overprints of land defenses and underwater obstacles provided with these charts arrived too late to be of maximum benefit to the troops: the land defense overprint for the Admiralty Tide Chart was distributed after D-day. In addition, enemy defense information was not as recent as it might have been.38

Embarkation

After the briefings and final water proofing of their vehicles to withstand 41-foot depths, the troops split into vessel loads and moved to their embarkation points or herds. The 5th Engineer Special Brigade embarked at Portland, Weymouth, and Falmouth between 31 May and 3 June. Elements of the brigade scheduled for the first two tides with Force O loaded aboard troop transports (APs and LSIs), landing ships and craft (LSTs, LCTs, and LCIs), cargo freighters, and motor transport ships.

Like other components of the assault force, the engineers were to go ashore in varied craft to reduce the risk of losing an entire unit in the sinking of a single vessel. Each unit of the brigade had an assigned number of personnel and vehicle spaces, and the total was considerable 4,188 men and 327 vehicles, including attached nonengineer units. Force B scheduled to land on the third tide with 1,376 men and 277 vehicles, loaded on a single wave for better control on the assumption that the risk of losing vessels would be much less by the time of its landing.39 The 1st Engineer Special Brigade units in Force U loaded at Plymouth, Dartmouth, Torquay, and Brixham beginning on 30 May. The assembly of Force U was somewhat more difficult than that of Force O because its loading points were more widely scattered.40

Most assault demolition teams were jammed aboard 100-foot LCTs, each already carrying two tanks, a tankdozer, gear, and packs of explosives in addition to its own crew. When they arrived at the transport area, the teams were to transfer to fifty-foot LCMs to make the run to the beach. Because insufficient lift was available to carry the LCMs in the customary manner, such as on davits, LCTs towed them to the transport area.41

Before midnight of 3 June the engineers were aboard their ships and on their way to their rendezvous points beyond the harbors. D-day was to be 5 June. The slow landing ships and craft of Force U got under way during the afternoon of 3 June because they had the greatest distance to go; those of Force O sortied later in the evening. The night was clear but the wind was rising and the water was becoming choppy. At dawn, after a rough night at sea, the vessels were ordered to turn back. D-day had been postponed. Sunday, 4 June, was a miserable day for the men jammed aboard the landing ships and craft under a lashing rain.

At dawn next morning the order went out from the supreme commander that D-day would be Tuesday,

[317]

6 June. The word came to many of the engineers as it did to those of the 147th Engineer Combat Battalion aboard LCI-92:

Suddenly a hush spread above the din and clamor of the men.... And then, as if coinciding with silence, a clear, strong voice extending from bow to stern, and reaching every far corner of the ship, announced the Order of the Day issued by the Supreme Commander. The men strained to catch every word, "you are about to embark on the Great Crusade.... Good Luck! And let us all beseech the blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking." For the next few moments, heads were bowed as if in silent prayer. This was the word. Tomorrow was D-day.42

[318]