CHAPTER XV

The Landings on OMAHA and UTAH

Darkness over the English Channel on the night of 5 June 1944 concealed five thousand ships, spread over twenty miles of sea, plowing the choppy waters toward Normandy. Two American and three British task forces traveled their separate mine-swept lanes to the midpoint of the Channel. Each lane divided there into two sublanes, one for the naval fire support vessels and the faster transports, the other for slower craft jammed with tanks, field pieces, and wheeled vehicles.

Force O, destined for OMAHA, and Force U, headed for UTAH, arrived in designated transport areas ten miles off the French coast after midnight, and the larger ships began disgorging men and equipment into the assault LCVPs swinging down from the transports' davits and hovering alongside. Smaller landing craft churned around the larger ships with their own loads of infantry, equipment, and armor for the assault. LCTs carried the duplex-drive amphibious Sherman tanks that would play a vital part in the first moments of the invasion. The spearhead of the assault on OMAHA, the tanks were to enter the water 6,000 yards offshore, swim to the waterline at Dog White and Dog Green, and engage the heavier German emplacements on the beaches five minutes ahead of the first wave of infantry.

At H-hour, 0630, with the tide just starting to rise from its low point, another wave of Shermans and tankdozers was to land on Easy Green and Dog Red, followed a minute later by the assault infantry in LCVPs and British-designed armored landing craft called LCAs. At 0633 the sixteen assault gapping teams were due on OMAHA, and their support craft were to follow them during the next five minutes. The demolition teams, with the help of the tankdozers, had just under half an hour to open gaps in the exposed obstacle belts before the main body of the infantry hit the beaches. The later waves also had combat engineers to blow additional gaps, clear beach exits, aid assault troops in moving inland, and help organize the beaches. Off UTAH a similar scene unfolded, with the duplex-drive tanks scheduled to go in on the heels of the first wave of the 8th Infantry assault, followed in five minutes by the Army-Navy assault gapping teams and detachments from two combat engineer battalions.1

Engineers on OMAHA

The eight demolition support teams

[319]

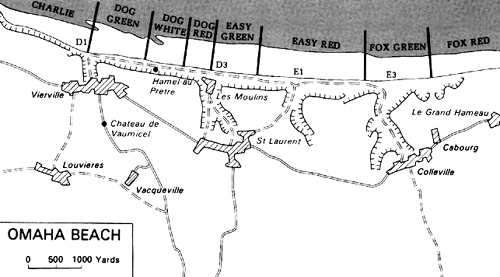

for OMAHA and the three command teams aboard a British transport had had a chance to get some sleep during the night. But the gapping teams, crowded aboard LCTs and towed LCMs, were miserable. One of the LCTs had broken down early in the voyage, and several swamped in the Channel swell. Their drenched and seasick passengers transferred to the bucking LCMs in the blackness, no small feat considering the amount of equipment involved. (Map 16)

The engineers were overburdened for their trip to shore. Each man carried a forty-pound bag of Hagensen packs, wire cutters, a gas mask, cartridges, an inflatable life belt, a canteen, rations, and a first aid packet. They had either carbines or Garand rifles and bangalore torpedoes to tear apart the barbed wire on the beach. Some had mine detectors, others heavy wire reels wound with 800 feet of primacord, and some carried bags of fuse assemblies. Over their uniforms all wore coveralls impregnated against gas, and over them a fur-lined jacket. Each LCM held two rubber boats, each containing about 500 pounds of explosives, extra bangalores, mine detectors, gap markers, buoys, and from 75 to 100 cans of gasoline.2

Almost from the beginning, things began to go wrong for the sixteen gapping teams. They managed to transfer from the LCTs to the LCMs on schedule, around 0300. At 0450, twenty minutes after the amphibious tanks and the first infantry assault wave started for shore, the demolition teams were on their way to the line of departure, some two miles offshore. Behind them, their support teams were delayed when their LCMs failed to arrive on time, and they encountered difficulties getting into smaller craft from the attack transports. Unable to load completely until 0500, the support elements finally got under way at 0600, far too late to reach the tidal flat in time to help the gapping teams. The precisely timed schedules, conceived for fair weather and calm seas, were breaking down even before the engineers reached the shore.3

The assault gapping teams headed landward heartened by the rain of metal descending on enemy positions. The eight assault teams assigned to the eastern sector of OMAHA with the 16th Regimental Combat Team reached the line of departure at first light; Navy control boats herded them into their correct lanes for Easy Red and Fox Green beaches. As they headed for shore, heavy shells of the naval bombardment whistled over their heads, and at 0600 bombers arrived with the first of some 1,300 tons of bombs dropped on the invasion area on D-day. The sight made the drenched, shivering men in the boats momentarily forget their misery. They were cheered in their certainty that the Air Forces would saturate the beaches, and when a British rocket ship loosed the first of a barrage of 9,000 missiles at the German positions, hope mounted that the German artillery and machine-gun nests would be silent when the LCMs came in. Optimists recalled a statement from a briefing aboard one of the transports: "There will be nothing alive on the

[320]

MAP 16

beach when you land."4

The illusion did not sustain them long, for the bombers had flown through cloud cover that forced their crews to rely on imperfect blind bombing techniques. Only two sticks of bombs fell within four miles of the shore defenses, though the area behind the beaches took a thorough pounding. The British rockets made a fine display, but disappeared over the cliffs to dig up the landscape behind the German coastal works. The naval barrage beginning at H minus 45 minutes was also more effective inland, contributing to the disruption of German communications. The combined power of the air and naval bombardment did much to isolate the battle area. But the German shore batteries on OMAHA, located in bunkers and enfilading the beach so that they could fire no more than a few hundred yards out to sea, remained mute during the opening moments of the action. Offering no muzzle flashes to give away their positions to the Navy gunners and invite their own destruction, they were largely intact when the first wave of engineers, tanks, and infantry hit the tidal flat.5

For the first troops in, OMAHA was "an epic human tragedy which in the early hours bordered on total disaster."6 The morning mists and the smoke raised in the bombardment concealed landmarks in some sectors, and a strong tidal crosscurrent carried the boats as

[321]

TANKS AND VEHICLES STALLED AT THE SHINGLE LINE ON OMAHA BEACH

much as two thousand yards east of their intended landfalls. The 741st Tank Battalion launched twenty-nine of its thirty-two duplex-drive tanks offshore and immediately lost twenty-seven when they foundered or plunged directly to the bottom of the Channel upon leaving their LCTs. Two swam ashore, and the remaining three landed from beached LCTs, only to fall prey at the waterline to German gunners. Machine-gun fire whipped among the engineer and infantry landing craft, intermingled now, and followed them to the beach. As the ramps dropped, a storm of artillery and mortar rounds joined the automatic and small-arms fire, ripping apart the first wave. Dead men dotted the flat; the wounded lay in the path of the onrushing tide, and many drowned as the surf engulfed them. An infantry line formed at the shingle bank and, swelled by fearful, dispirited, and often leaderless men, kept up a weak volume of fire as yet inadequate to protect the engineers. In the carnage, the gapping teams, suffering their own losses, fought to blow the obstacles.

On the left of Easy Red, one team led the entire invasion by at least five minutes. The commander of Team 14, 2d Lt. Phill C. Wood, Jr., was under the impression that H-hour was 0620 instead of 0630. Under his entreaties, the Navy coxswain brought the LCM in at 0625, the boat's gun crew unsuccessfully trying to destroy Teller mines

[322]

on the upright stakes. Wood and his team dragged their explosive-laden rubber boat into waist-deep water under a hail of machine-gun fire. No one was on the beach. The lieutenant charged toward a row of obstacles, glancing backward as he ran. In that moment he saw an artillery shell land squarely in the center of the craft he had just left, detonating the contents of the second rubber boat and killing most of the Navy contingent of his team. The LCM burned fiercely. Wood's crew dropped bangalore torpedoes and mine detectors and abandoned their load of explosives. Dodging among the rows, they managed to wire a line of obstacles to produce a gap, but here the infantry landing behind them frustrated their attempt to complete the job. Troops, wounded or hale, huddled among the obstacles, using them for cover, and Wood finally gave up trying to chase them out of range of his charges. Leaving the obstacles as they were, he and his team, now only about half of its original strength, rushed forward and took up firing positions with the infantry concentrated at the shingle.7

Other teams had little more success. Team 13's naval detachment also fell when an artillery shell struck its boatload of explosives just after it landed on Easy Red. The Army contingent lost only one man but found the infantry discharging from the landing craft seeking cover among the obstacles, thus preventing the team from setting off charges. Team 12 left its two rubber boats aboard the LCM, yet managed to clear a thirty-yard gap on Easy Red, but at a fearful cost. A German mortar shell struck a line of primacord, prematurely setting off the charges strung about one series of obstacles, killing six Army and four Navy demolitions men and wounding nine other members of the team and a number of infantrymen in the vicinity. Team 11, arriving on the far left flank of Easy Red ahead of the infantry, lost over half its men. A faulty fuse prevented the remainder from blowing a passage through the beach impediments.

Only two teams, 9 and 10, accomplished their missions on the eastern sector of OMAHA. Team 9, landing in the middle of Easy Red well ahead of the infantry waves, managed to open a fifty-yard path for the main assault. Team 10's performance was encouraging in comparison with that of the others. Clearing the infantry aside within twenty minutes of hitting the beach, the men demolished enough obstacles in spite of heavy casualties to create two gaps, one fifty yards wide and a second a hundred yards across. They were the only gaps blown on the eastern half of the assault beaches.

The remaining teams assigned to that area had much the same dismal experience as Lieutenant Wood's team, and the failure of the assault gapping effort became evident. At Fox Green, Teams 15 and 16 came in later than those on Easy Red but met the same heavy artillery and automatic fire. At 0633 Team 16 plunged off its LCM, leaving its rubber boats adrift when it became apparent that they drew German attention. Here too the men gave up trying to blow gaps when the infantry would not leave the protection of the German devices. Team 15 touched down at 0640, just as the tide began rising rapidly,

[323]

and lost several men to machine-gun fire before they left the LCM. In a now common occurrence, they sustained more casualties when a shell found the rubber boat with its volatile load. The survivors nevertheless attacked the Belgian gates farthest from shore and fixed charges to several. The fusillade from shore cut away fuses as rapidly as the engineers could rig them. One burst of fragments carried away a fuseman's carefully set mechanism-and all of his fingers. With no choice but to make for shore, they ran, only four of their original forty uninjured, to the low shingle bank on Fox Green, where they collapsed, "soaking wet, unable to move, and suffering from cramps. It was cold and there was no sun.''8

Seven teams bound for the 116th Infantry's beaches on the western half of OMAHA-Dog Green, Dog White, Dog Red, and Easy Green-were on schedule, most of them, in fact, coming in ahead of the infantry companies in the first waves. The eighth team landed more than an hour later; its LCT had foundered and sunk shortly after leaving England, and the team transferred to other craft. When it finally landed at 0745, the team found the obstacles covered with water. The duplex-drive tank crews on the western half of the beach came in all the way on their landing craft rather than attempting the swim ashore, but their presence was only briefly felt. German fire disabled many tanks at the shingle line where they had halted, unable to move farther, and those remaining could not silence the heavier enemy guns. The men of Team 8, landing a little to the left of Dog Green, saw no Americans on the beach but confronted a German party working on the obstacles. The Germans fled, and the team was able to blow one fifty-yard gap before the American infantry arrived. Teams 3 and 4, badly shot up, achieved little, and Teams 5 and 7 could do no blasting after the incoming infantry took cover among the beach obstructions. The only positive results came when Teams 1 and 6 each opened a fifty-yard gap, one on Dog White and one on Dog Red. Command Boat 1, on the beach flat at 0645, unloaded a crew that made an equally wide hole in the obstacles on Easy Green. Where the engineers successfully blew lanes open, they had first to cajole, threaten, and even kick the infantry out of the way. Gapping team members later recalled that the teams had more success if they came in without firing the machine guns on the LCMs, since their distinctive muzzle flashes gave their range to the enemy.

The tardy support teams appeared off the eastern beaches, all carried off course and landing between 0640 and 0745 on or around Fox Red. The German artillerymen at the eastern reaches of OMAHA met them with fearsomely accurate fire. One 88-mm. piece put two rounds into Team F's LCM, killing and wounding fifteen men; only four men of the original team got to shore. Team D got a partial gap opened, making a narrow, thirty-yard lane, but the other teams could do little. The men arriving later found the German fire just as heavy, and the incoming tide forced them to shore before they could deploy among the obstacles. They joined the earlier elements that had found

[324]

shelter under the cliffs at the eastern end of the beach.9

Their strength reduced to a single machine, engineer tankdozers could offer little help. Only six of the sixteen M-4s equipped with bulldozer blades got ashore, and the enemy picked off five of them. The remaining one provided the engineers an alternative to blowing up the obstacles, an increasingly hazardous undertaking as more troops and vehicles crowded onto the beaches. Instead of using demolitions, which sent shards of metal from the obstacles careening around the area, the teams set about removing the mines from stakes, ramps, hedgehogs, and Belgian gates, and let the tankdozers, joined later in the day by several armored bulldozers, shove the obstacles out of the way as long as the tide permitted. Pushed ashore after 0800 by the inrushing water, the gapping teams helped move wounded men off the tidal flat and consolidated equipment and the supply of explosives to await the next ebb.

In the meantime the Navy had discovered that the obstacles did not pose the expected problem once they were stripped of their mines. Shortly after 1000, several destroyers moved to within a thousand yards of the beach. Engaging the German emplacements with devastating 5-inch gunfire, they began to accomplish what the tanks in the first assault could not. Using the covering fire, two landing craft, LCT-30 and LCI-554, simply rammed through the obstacles off Fox Green, battering a path to shore with all automatic weapons blazing. Though LCT-30 was lost to fire from the bluffs, the other vessel retracted from the beach without loss, and dozens of other craft hovering offshore repeated the maneuver with the same result.10

When the first morning tide interrupted the work of the gapping teams, they had opened just five holes, and only one of these, Team 10's 100-yard-wide lane on Easy Red, was usable. Their ranks virtually decimated in their first half-hour ashore, the teams' members were often bitter when they discussed their experience later. Most of the equipment the LCMs carried had been useless or worse; the rubber boats with their explosives had drawn heavy fire, and the engineers had abandoned them as quickly as possible. The mine detectors were useless since the enemy had buried no mines in the flat, and German snipers made special targets of men carrying them. With no barbed wire strung among the obstacles, the bangalore torpedoes the engineers brought in were only an extra burden. Overloaded and dressed in impregnated coveralls, the engineers found their movement impeded, and wounded and uninjured men alike drowned under the weight of their packs as they left the landing craft. The survivors also criticized the close timing of the invasion waves that left them only a half hour to clear lanes. The confusion produced when the engineers landed simultaneously with or even ahead of the infantry led to the opinion that there also should have been at least a half hour between the first infantry assault

[325]

and the arrival of the gapping teams. In future actions, support teams should go in with the groups they were backing up rather than behind them in the invasion sequence. Lastly, as a tactical measure, the gapping team veterans recommended that the first concern should be to strip the mines from any obstacles encountered so as to render them safe for tankdozers or landing craft to ram.11

The human cost of the engineers' heroism on OMAHA was enormous. When the Army elements of the gapping teams reverted on D plus 5 to control of the 146th and 299th Engineer Combat Battalions, then attached to V Corps, they had each lost between 34 and 41 percent of their original strength. The units had not yet accounted for all their members, and the Navy set losses among the naval contingents of the teams at 52 percent. Fifteen Distinguished Service Crosses went to Army members of the team; Navy demolitions men received seven Navy Crosses. Each of the companies of the 146th and 299th Engineer Combat Battalions involved and the naval demolition unit received unit citations for the action on D-day.12

The end of the first half hour on D-day saw approximately 3,000 American assault troops on OMAHA, scattered in small clumps along the sand. Isolated from each other and firing sporadically at the enemy, they sought to advance up the small defiles leading to the flanks and rear of German positions, but no forward motion was yet evident. On the right, or western, flank of the beach in front of Vierville in the 116th Infantry's zone, the Germans had taken the heaviest toll among the incoming men, and the assault of Company A, 116th Infantry, crumbled under the withering fire. Reinforcements were slow, often carried off course to the east in the tidal current. A thousand yards east, straddling Dog Red and Easy Green, lay elements of two more companies from the 116th, confused by their surroundings but less punished by German fire since the defensive positions above were wrapped in a heavy smoke from grass fires that obscured vision seaward. Sections of four different companies from both assault regiments landed on the Fox beaches and, huddled with engineers from the gapping teams, fired at opportune targets or contemplated their next moves. Only in the stretch between the Colleville and St. Laurent draws, Exits E-1 and E-3, was there relative safety. The German posts in the bluffs here seemed unmanned through the whole invasion, which also permitted the more successful performance of the gapping teams on Easy Red. But the success of the invasion on OMAHA now depended upon getting the troops and vehicles off the beaches and through the German coastal defensive shell.13

Opening the Exits

While the ordeal of the gapping teams was still in progress, a second phase of

[326]

engineer operations on OMAHA began with the arrival of the first elements of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade. These units were charged with bringing some order out of the chaos of the invasion beaches. For the purpose some engineer combat battalions became the core units for beach groups, which included a DUKW company, quartermaster units for gasoline and other supply, a medical detachment, ordnance ammunition, maintenance, and bomb disposal units, and an assortment of signal, chemical, and military police companies. A company from a naval beach battalion completed the organization to assist in structuring the beaches for supply operations. Four groups had assignments on OMAHA for D-day. The 37th Engineer Battalion Beach Group supported the 16th Regimental Combat Team, 1st Division, and the 149th was behind the 116th Infantry. The 348th was to facilitate the landing of the 18th Infantry, following the 16th on the eastern end of the beach. The 336th Engineer Battalion Beach Group was scheduled to arrive in the afternoon to organize Fox Red. All the groups were under 5th Engineer Special Brigade control until the assault phase was over; the 149th Engineer Battalion Beach Group would then revert to the 6th Brigade.14

The earliest elements stepped into the same fire that cut up the gapping teams. First in was a reconnaissance party from Company A, 37th Engineer Combat Battalion, led by the company commander; it landed at 0700, ten minutes ahead of schedule, opposite the E-3 draw on Fox Green. Sections of the remainder of Company A and a platoon of Company C, accompanying a headquarters group, arrived over the next several minutes, but the entire complement of the battalion's men wound up hugging the shingle bank and helping to build up the fire line. Another engineer section, this one from Company C, 149th Engineer Combat Battalion, scheduled for landing on Dog Red, landed on Easy Green. They set to work there, and a small detachment began digging a path through the dune line to the road paralleling the shore. A second detail wormed its way through gaps cut in the barbed wire and approached the base of the cliffs, only to be halted by an antitank ditch. Enemy fire forced the group back to the shingle line. Two companies from the 147th Engineer Combat Battalion suffered forty-five men lost to artillery fire even before their LCT set them down off Dog White at 0710. In the five-foot surf they lost or jettisoned their equipment and found shelter after a harrowing run for the shingle.15 An LCI put Company B, 37th Engineer Combat Battalion, ashore safely at 0730 at Exit E-1, leading to St. Laurent, which the battalion was supposed to open for the 2d Battalion of the 16th Infantry. Company A was to open Exit E-3 for the 3d Battalion but did not arrive until 0930. Landing near E-1, Company A had to make its way through the wreckage on the beach to E-3, where the unit ran into such withering artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire that it could accomplish little all day. Unluckiest of all was Company C, which was to push inland and set up transit areas. A direct hit to its LCI on landing at Exit E-1 killed many men. In the same area one

[327]

of two LCIs carrying the battalion staff broached on a stake; the men had to drop off into neck-deep water and wade ashore under machine-gun fire.16 Coming in with the fifth wave, they had expected to find OMAHA free of small arms fire. Instead, the beach was crowded with the men of the first waves crouching behind the shingle. Deadly accurate artillery fire was still hitting the landing craft, tanks, and half-tracks lining the water's edge; one mortar shell killed the commander of the 37th Engineer Combat Battalion, Lt. Col. Lionel F. Smith, and two members of his staff, Capts. Paul F. Harkleroad and Allen H. Cox, Jr., as soon as they landed. Badly shaken, the engineers joined the infantrymen behind the shingle bank.

By 0930, infantry penetrations of the German positions above the beach were beginning to have some effect, though only a few men were scaling the heights. Rangers and elements of the 116th Infantry got astride the high ground between Exits D-1 and D-3 around 0800 and slowly eliminated some of the automatic weapons trained on American troops below. Between St. Laurent and Colleville, companies from both regiments got men on the heights. One company raked the German trenches in the E-1 draw, capturing twenty-one Germans before moving farther inland. In the F-1 draw back of Fox Red, most coordinated resistance ended by 0900, but isolated nests of Germans remained. The movement continued all morning, and the engineers either joined attempts to scale the bluffs or made it possible for others to climb.

Beyond the shingle on Easy Green and Easy Red were a double-apron barbed-wire fence and minefields covering the sands to the bluffs. As the infantry advances began to take a toll of the German defenders on the bluffs, Sgt. Zolton Simon, a squad leader in Company C, 37th Engineer Combat Battalion, gathered his five-man mine-detector crew, cut a gap in the wire, and led his men into the minefield. Disregarding the fire, they methodically opened and marked a narrow path across the mined area, into a small defile, and up the hill. Simon was wounded once while helping to sweep mines and again when he reached the hilltop, this time so seriously that he was out of action. By now, infantry was on the trail behind him, urged into the gap by 1st Lt. Charles Peckham of Company B. who stood exposed to enemy fire directing men across the mine-swept corridor.17

The task remained of getting the tanks inland. A platoon of the 20th Engineer Combat Battalion, landing in support of the 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry, began blowing a larger gap through the minefield with bangalore torpedoes. Mine-detector crews of Company C of the 37th Engineer Battalion followed to widen the lanes to accommodate vehicles. But the tanks could not get past the shingle, where they could get no traction. Behind the shingle lay a deep antitank ditch. Pvt. Vinton Dove, a bulldozer operator of Company C, made the first efforts to overcome these obstacles, assisted by his relief operator, Pvt. William J. Shoemaker, who alternated with him in driving and guiding the bulldozer. Dove cleared a

[328]

ENGINEERS ANCHOR REINFORCED TRACK for vehicles coming ashore at OMAHA.

road through the shingle, pulled out roadblocks at Exit E-1, and began working on the antitank ditch, which was soon filled with the help of dozer operators from Company B and a company of the 149th Engineer Combat Battalion that had landed near E-1 by mistake. The pioneer efforts of Dove and Shoemaker in the face of severe enemy fire, which singled out the bulldozer as a prime target, won for both men the Distinguished Service Cross.18

Company C's 1st Lt. Robert P. Ross won the third of the three Distinguished Service Crosses awarded to men of the 37th on D-day for his contribution to silencing the heavy fire coming from a hill overlooking Exit E-1. Assuming command of a leaderless infantry company, Ross took the infantrymen, along with his own engineer platoon, up the slopes to the crest, where the troops engaged the enemy, killed forty Germans, and forced the surrender of two machine-gun emplacements.19 Cleared fairly early, the E-1 exit became the principal egress from OMAHA Beach on D-day, largely due to the exertions of the 37th Engineer Combat Battalion. The unit suffered the heaviest casualties among the components of the 5th

[329]

Engineer Special Brigade-twenty-four men killed, including the battalion commander.

Exit E-3 yielded only slowly to the persistence of the engineer troops in the area, including Company A, 37th Engineer Combat Battalion. Still under accurate if intermittent artillery fire around 1630, the beach remained unmarked for incoming boat traffic, as the shelling tore down the signposts as soon as they were erected. By 1700 the 348th Engineer Combat Battalion had cleared the lateral road along the beach of mines, and the members of both battalions moved to the base of the uplands to begin work in the draw, already choked with wrecked American tanks and half-tracks. Night drew on as the men opened the road leading up from the beach. A particularly troublesome 88-mm. gun interfered with their work until dark, and Capt. Louis J. Drnovich, commanding Company A, 37th Engineers, determined that he "would get that gun or else." Taking only his carbine and a few grenades, he set off up the hill. His body was found three days later a short distance from where he had started. The exit carried its first tank traffic over the hill to Colleville at 0100 on D plus 1, but trucks could not negotiate the road until-morning.20

By that time, tanks were moving to Colleville through Exit F-1, easternmost in the 16th Infantry's sector and close to bluffs dominating Fox Red. This was the sector where many troops of the first assault waves, including some of the 116th Regimental Combat Team, had landed as a result of the easterly tidal current. The task of opening Exit F-1 belonged to the 336th Engineer Battalion Beach Group, which was scheduled to land after 1200 on D-day at Easy Red near E-3 and then march east to Fox Red. Some of the advance elements went ashore on E-3 at 1315 and made their way toward their objective through wreckage on the beach, falling flat when enemy fire came in and running during the lulls.21

Heavy enemy fire drove away two LCTs carrying three platoons of Company C, and the platoons landed at the end of OMAHA farthest from the Fox beaches. An artillery shell hit one LCT; the other struck a sandbar. Both finally grounded off the Dog beaches between Les Moulins and Vierville-the most strongly fortified part of OMAHA, where stone-walled summer villas afforded protection to German machine gunners and snipers and the cliffs at the westward end at Pointe de la Percee provided excellent observation points for artillery positions behind the two resorts. This was the area of the 116th Regimental Combat Team, whose engineer combat battalions-the 112th, 121st, and 147th-suffered severely during the landings.

Survivors of the first sections of the 147th Engineer Combat Battalion to come in on Dog White at 0710 joined infantrymen in the fight for Vierville or climbed the cliffs with the Rangers. At midmorning the battalion commander, concerned about a growing congestion of tanks and vehicles on Dog Green, ordered all his units to concentrate on blowing open Exit D-1, blocked by a concrete revetment. They set to work, collecting explosives from dead bodies and wrecked vessels, and with

[330]

the help of men of the 121st Engineer Combat Battalion, who had mislanded on Easy Green and had made their way to Dog Green, were able to open the exit, but it was not fully usable until 2100. At Exit D-3, the Les Moulins draw between Dog Red and Easy Green, the 112th Engineer Combat Battalion commander was killed early on D-day, and the men were pinned down by enemy fire behind a seawall. Even with the assistance of a platoon of the 147th, which came in with most of its equipment during the day, the 112th Battalion was not able to open Exit D-3 until 2000.22

Wading ashore at Dog Green about 1500, troops of the 336th Engineer Combat Battalion assembled at the shingle bank and began a hazardous march toward Fox Red, more than two miles away. The unit moved in a long irregular column, followed by a D-7 tractor that towed an Athey trailer loaded with explosives. As the battalion made its way around bodies and wreckage through smoke and gunfire, it witnessed the awful panorama of D-day on OMAHA. Artillery fire had decreased at Exit D-1 after destroyers knocked out a strongpoint on Pointe de la Percee about noon. It grew heavier as engineers approached Exit D-3, several times narrowly missing the explosive-laden trailer. At E-1 the fire let up, but congestion on the beach increased. Bulldozers were clearing a road through the shingle embankment, and the beach flat was jammed with vehicles waiting to join a line moving up the hill toward St. Laurent. DUKWs with 105-mm. howitzers were beginning to come in; the first (and only) artillery mission of the day from the beach was fired at 1615 against a machine-gun nest near Colleville.

The worst spot they encountered on the beach was at Exit E-3, still under fire as they passed. There the 336th Battalion's column ran into such heavy machine-gun fire and artillery shelling that the unit had to halt. The commander sent the men forward two at a time; when about half had gone through the area, a shell hit a bulldozer working at the shingle bank. The dozer began to burn, sending up clouds of smoke that covered the gap and enabled the rest of the men to dash across. As the troops proceeded down the beach, they saw a tank nose over the dune line and fire about twenty-five rounds at a German machine-gun emplacement, knocking it out; but artillery barrages continued hitting the beach in front of E-3 every fifteen or twenty minutes.

At the end of its "memorable and terrible" march across OMAHA, during which two men were killed by shell fray meets and twenty-seven were injured, the engineer column reached the comparative safety of the F-1 area at 1700. The surrounding hills had been cleared of machine-gun nests, and although enemy artillery was able to reach the tidal flat, it could not hit the beach. The first job was mine clearance: the area was still so heavily mined that several tanks, one of them equipped with a dozer blade, could not get off the beach. The men had only one mine detector but were able to assemble several more from damaged detectors the infantry had left on the beach. More were salvaged when the last elements of the battalion came in from Dog Green around 1730. After they had cleared the fields

[331]

near the beach of mines and a tankdozer had filled in an antitank ditch, the teams began to work up a hill with a tractor following, opening the F-1 exit. Tanks began climbing the hill at 2000; two struck mines, halting the movement for about an hour, but by 2230 fifteen tanks had passed through the exit to the Colleville area to help the infantry clear the town.23

Brig. Gen. William M. Hoge, commanding general of the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group, had landed at Exit E-1 shortly after 1500 and had set up a command post in a concrete pillbox just west of the exit; from there he assumed engineer command responsibility from the 5th Engineer Special Brigade commander, Col. Doswell Gullatt. As units of the 6th Engineer Special Brigade reverted to that unit, additional infantry units were landing to support the 116th and the 16th Infantry. The 115th, ahead of schedule and also carried eastward, landed in the middle of the lath Infantry, east of the St. Laurent draw. This produced some confusion, but the new strength swelled the advance moving slowly off the beaches by evening. In the morning of D plus 1 vehicular traffic, infantry, and engineers alike were moving through the exits, off the beaches, and over the hills. By that time the 4th Infantry Division of Force U had penetrated the German defenses some ten miles to the west at UTAH Beach.24

UTAH

As the first assault elements transferred into landing craft a dozen miles off UTAH, alarmed German local commanders were trying to fathom the intentions and to gauge the strength of the paratroopers that had dropped into their midst around 0130. Separated in the cloud cover over the Cotentin peninsula while evading German antiaircraft fire, the transport aircraft headed for partially marked drop zones astride the Merderet River and the area between Ste. Mere-Eglise and UTAH itself. Scattered widely in the drop, the troopers of the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions struggled to concentrate their strength and find their objectives. The 82d had one regiment fairly consolidated from the start east of the Merderet. The division took the town of Ste. Mere-Eglise with mixed contingents, some troops from the 101st working with the 82d even as glider-borne reinforcements came in shortly before dawn. The 101st Airborne Division, equally dispersed, managed to mass enough of its own men and troopers of the 82d who fell into its area of responsibility to secure the western edges of the inundated land behind UTAH and the all-important causeway entrances on that side of the German beach defenses. With German strength threatening the landing zone from across the Douve River to the south, the paratroopers could not muster enough men to control or destroy all the bridges across the river. Engineers of Company C, 326th Airborne Engineer Battalion, rigged some for destruction, and small groups held out nearly all of D-day in the face of German units south of the stream, awaiting relief by other airborne units or by the main body of the invasion. Their losses and their disorganization notwithstanding, the paratroops had thoroughly confused the

[332]

German defenders and engaged their reserves, especially the veterans of the 91st Division, far from the beaches.25

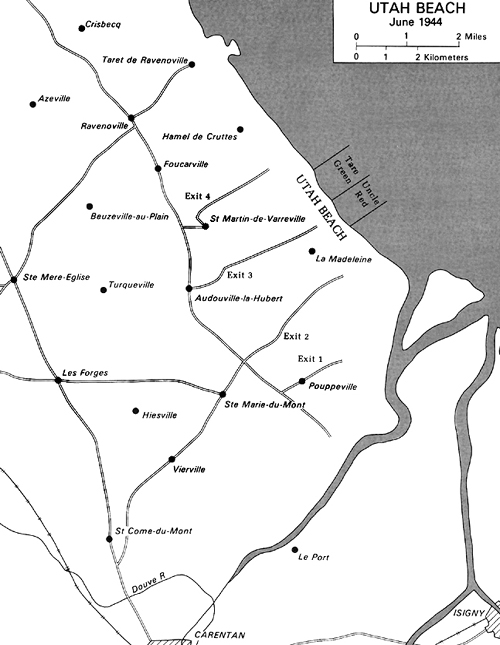

Compared with OMAHA, UTAH was practically a walkover. Owing to the smoke of the prelanding bombardment and the loss of two small Navy control vessels marking the line of departure off the beach, the entire first wave of the 8th Infantry's assault grounded 2,000 yards south of its intended landfall. The operation of UTAH shifted to the left of the original beaches, fortuitously striking a shoreline far less heavily defended and with much sparser obstacle belts than expected. (Map 17)

Engineer demolitions were to begin at 0635, five minutes after the infantry landing. The teams involved were under an ad hoc Beach Obstacle Demolition Party commanded by Maj. Herschel E. Linn, also the commanding officer of the 237th Engineer Combat Battalion. Underwater obstacles above the low tide line were the targets of the first demolition units, eight sixteen-man naval teams, each including five Army engineers. Eight of the twelve available 26-man Army demolition teams were to land ten minutes later, directly behind eight LCTs carrying the dozer tanks to be used on the beach. Navy and Army teams were to clear eight fifty-yard gaps through the beach obstructions for the subsequent waves, and the fourth and fifth waves of the assault would bring in the remainder of the engineers to help clear the area as necessary. Linn and his executive of ricer, Capt. Robert P. Tabb, Jr., planned to supervise the beach operations from their M-29 Weasels, small tracked cargo vehicles capable of negotiating sand and surf.26

The plan came apart immediately. Army and Navy teams landed almost simultaneously between 0635 and 0645. On the run to the beach, Major Linn's craft was sunk off Uncle Red; he did not arrive ashore until the following day. Captain Tabb, now in command, drove his Weasel off the LCT on Tare Green and felt it sink beneath him. He salvaged the radio after getting the crew out and made for the beach, where he encountered Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., assistant commander of the 4th Infantry Division, walking up and down the seawall back of UTAH and directing operations. At the time enemy fire was so much lighter than expected that the landing seemed to Tabb almost an anticlimax. Except for six Army engineers, who were killed when a shell hit their LCM just as the ramp dropped, all the demolition men got ashore safely and immediately began to blast gaps in the obstacles. About half were steel and concrete stakes, some with mines attached to the top; the rest were mostly hedgehogs and steel tetrahedrons, with only a few Belgian gates.27

The four Army gapping support teams landed on the northern part of Tare Green Beach at 0645 after a harrowing trip from the transport area. They had been aboard an attack transport with the commanding officer of the 1106th Engineer Combat Group, Col. Thomas DeF. Rogers. Rogers discovered at the last minute that no provision

[333]

had been made for getting the reserve teams ashore, and he arranged with the ship's commander to load the whole party of ninety-three men, with explosives, into a single LCM. Rogers went along in the dangerously overloaded craft, proceeding shoreward at full speed. Landing in an area where no gap had been blown, he got the men to work and then walked southward down the beach to inspect the work the leading teams were doing. The Army and Navy teams had partly blown fifty-yard gaps, which Rogers instructed them to widen to accommodate the landing craft bunching up offshore. He saw two tankdozers in use but observed that gaps were cleared mainly by hand-placed charges connected with primacord.

The work went on under artillery fire that increased at both the southern and northern gaps after H-hour. Rogers and others were deeply impressed by the heroism of the men, but casualties were light compared to those on OMAHA. The Army teams had 6 men killed, 39 wounded; the Navy teams, 4 killed and 11 wounded. The initial gaps were cleared by 0715. Then the demolitionists worked northward, widening cleared areas and helping demolish a seawall. By 0930 UTAH Beach was free of all obstacles. The Navy teams went out on the flat with the second ebb tide and worked until nightfall on the flanks of the beaches, while by noon the Army teams were ready to assist the assault engineers in opening exit roads.28

While the demolitionists were blowing the obstacles, Companies A and C of the 237th Engineer Combat Battalion, which had landed with the 8th Infantry at H-hour, were blowing gaps in the seawall, removing wire, and clearing paths through sand dunes beyond. For these tasks the two companies had bangalore torpedoes, mine detectors, explosives, pioneer tools, and markers. Later in the morning they received equipment to bulldoze roads across the dunes.29

Beyond the dunes was the water barrier, running a mile or so inland from Quineville on the north to Pouppeville on the south, which the Germans had created by reversing the action of the locks that the French had constructed to convert salt marshes into pastureland. Seven causeways crossed the wet area in the region of the UTAH landings to connect the beach with a north-south inland road. Not all the causeways were usable on D-day. Most were under water; the northernmost, although dry, was too close to German artillery. The best exits were at or near the area where the troops had landed-another stroke of good fortune. Exit T-5, just north of Tare Green Beach, was flooded but had a hard surface and was used during the night of D-day. Exit U-5 at Uncle Red was above water for its entire length and became the first route inland, leading to the village of Ste. Marie-du-Mont. South of U-5, some distance down the coast near Pouppeville and the Douve River, lay the third road used on D-day, Exit V-1. Although in poor condition, the road was almost completely dry.30

[334]

MAP 17

[335]

TELLER MINE ATOP A STAKE emplaced to impale lasting on UTAH Beach.

At the entrance to Exit U-5 the Germans had emplaced two Belgian gates. Company A, 237th Engineer Combat Battalion, blew them and also picked up several prisoners from pillboxes along the seawall. Then the engineers accompanied the 3d Battalion, 8th Infantry, inland along Exit U-5. Halfway across the causeway they found that the Germans had blown a concrete culvert over a small stream. The column forded the stream and proceeded, leaving Captain Tabb to deal with the culvert. He brought up a bridge truck and a platoon of Company B to begin constructing a thirty-foot treadway bridge-the first bridge built in UTAH bridgehead. Men of the 238th Engineer Combat Battalion, who had landed around 1000 with the main body of the 1106th Engineer Combat Group, helped. By 1435, Exit U-5 was open to traffic.31

Two companies of the 49th Engineer Combat Battalion, also landing with the 1106th in midmorning, accompanied the 2d Battalion, 8th Infantry, on its march south to Pouppeville. The engineers were to work on Exit V-1 leading from the beach through Pouppeville to the north-south inland road, while infantry was to make contact with the 101st Airborne Division, protecting the southern flank of VII Corps. Company G of the 8th Infantry also had the mission of capturing the sluice gates or locks southeast of Pouppeville that the Germans had manipulated to flood the pastureland behind Tare Green and Uncle Red beaches. An enemy strongpoint still farther south at Le Grand Vey protected the locks.32

While Company E of the 8th Infantry moved down the road along the eastern edge of the inundations, Company G hugged the seawall. All the way down the coast the two companies encountered continuous small-arms fire, and Company G met artillery fire from a strongpoint on the seaward side about halfway down. At a road junction northeast of Pouppeville, the infantry battalion assembled and advanced to the village, where shortly after noon occurred the first meeting of seaborne and airborne troops on D-day.

[336]

During the probe to Pouppeville the infantrymen bypassed the sluice gates. But Company A of the 49th Engineer Combat Battalion moved south, secured the locks, took twenty-eight prisoners, and dug in to protect the locks from recapture. Next day the company overcame the German strongpoint at Le Grand Vey, capturing fifty-nine prisoners, seventeen tons of ammunition, large quantities of small arms, and three artillery pieces, which the engineers used to reinforce their defenses. During the next few days, with the aid of a platoon of Company B. Company A continued to hold its position, protecting the south flank of the beachhead and operating the locks to drain the water barrier.33

Except for the 49th Engineer Combat Battalion, which bivouacked near Pouppeville, all elements of the 1106th Engineer Combat Group including the beach obstacle demolitionists went into bivouac on the night of D-day at Pont Hebert, a village on the north-south inland road about halfway between causeways U-5 and V-1. Total D-day casualties for the group had been seven men killed and fifty-four wounded. For a few days work on the exits continued, but the next major task for the group was to help the 101st Airborne Division cross the Douve River. Improving the causeways, clearing and developing Tare Green and Uncle Red, and opening new beaches then became the responsibility of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade.34

When Brig. Gen. James E. Wharton, commanding the 1st Engineer Special Brigade, landed on UTAH at 0730 on D-day he found his deputy, Col. Eugene M. Caffey, already on the beach. Not scheduled to land until 0900, Caffey had smuggled himself, with no equipment except an empty rifle, aboard an 8th Infantry landing craft. En route he managed to load his rifle by taking up a collection of one bullet each from eight infantrymen. He arrived ashore very early in the assault and found General Roosevelt in a huddle with infantry battalion commanders, debating whether to bring later waves in on the actual place of landing or to divert them to the beaches originally planned. Men of the 8th Infantry were already moving inland on Exit U-5. The decision was made. "I'm going ahead with the troops," Roosevelt told Caffey. "You get word to the Navy to bring them in. We're going to start the war from here."35

The first elements of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade to land were men of the 1st and 2d Battalions, 531st Engineer Shore Regiment, who came in about the same time as Wharton. They set to work widening gaps the combat engineers had blown in the seawall, searching out mines, improving exits, and undertaking reconnaissance. Because one of the main tasks of the engineer regiment was to open Sugar Red, a new beach to the north of Tare Green, the officers reconnoitered the area, and elements of the 2d Battalion partially cleared it in preparation for its complete clearance and operation by the 3d Battalion, scheduled to arrive on the second tide. The brigade headquarters

[337]

ROADS LEADING OFF THE BEACHES opened by engineers, 8 June 1944.

was ashore by noon, and at 1400 Wharton established his command post in a German pillbox at La Grande Dune, a small settlement just beyond the dune line and near the entrance to Exit U-5.

Less than half of the road-building equipment the engineers counted on reached shore on D-day. Twelve LCTs were expected, but only five landed safely, all on the second tide. German shells hit three of the remainder, and the other four were delayed until D plus 1. Many engineer vehicles drowned out when they dropped into water too deep; hauling out such vehicles of all services was one of the heaviest engineer tasks on D-day, and a good deal of the work had to be done under artillery fire. Artillery accounted for most of the D-day casualties in the brigade twenty-one killed and ninety-six wounded; strafing by enemy planes, which came over in the evening, caused most of the rest.

By nightfall of D-day the brigade engineers had opened Sugar Red, and had made the road leading inland from it (Exit T-5) passable for vehicles. They had cleared beaches of wrecked vehicles and mines, had improved the existing lateral beach road with chespaling (wood and wire matting), and had set up markers. The brigade's military police were helping traffic move inland. The engineers had also established dumps for ammunition and medical

[338]

supplies and had found sites for other dumps behind the beaches.36

Despite the doubts and fears of the early hours on OMAHA, the invasion was successful. To be sure, the troops were nearly everywhere behind schedule and nowhere near their objectives behind OMAHA, but at UTAH the entire 4th Division got ashore within fifteen hours after H-hour with 20,000 men and 1,700 vehicles. In the UTAH area, the fighting remained largely concentrated in battalion-size actions and scattered across the segments of French terrain tenuously head by American airborne units. Nevertheless, the Allied forces had a strong grip on a beachhead on the Continent, and German counterattacks were feeble at best. The job of the next few days was to consolidate the flow of supply across the beaches and through the artificial port complex that the invasion force had brought with it across the Channel. Despite the tragic losses among the gapping teams and the collapse of their efforts on D-day, the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group by D plus 1 had provided the early basis for the supply organization on the beaches that would operate until the end of the year. Backlogs of invasion shipping fed by factors beyond the engineers' control developed immediately Off both beaches, and the limited numbers of trucks and DUKWs available affected supply movement just behind the shore. But on balance, the engineers' contribution in ingenuity and blood in the Normandy assault was immeasurable.

[339]