CHAPTER XII

The Chemical Mortar in the ETO

Getting chemical mortar battalions for the European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army, proved to be a complicated and difficult problem. Colonel Rowan, chief chemical officer in the theater, had recommended a total of 24 battalions for the theater troop list, a figure based upon the formula of 2 battalions per corps (18) and 2 additional battalions per army (6). His commander approved this recommendation, including the figure in the over-all troop list, which was forwarded to Washington early in 1943.1

The War Department took no action on the troop basis recommended by the theater commander. In November 1943 it sent an officer to England to inform the theater commander on War Department troop basis policy-the establishment of an over-all theater personnel ceiling within which the theater commander could set up his own troop basis. The officer produced a list of those units which were immediately available, those which were in training, and those which were scheduled for activation. He stated that the theater commander could take his pick, staying, of course, within his over-all ceiling. Because the list admittedly had no relation to the one submitted by the ETO, a situation which negated a large amount of detailed theater planning, the War Department agreed to activate and train units not on the list, with the understanding that this would take additional time. Unfortunately, there were only seven chemical mortar battalions on the list.

Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, commander of the US army group in the theater, received the job of determining the final troop list. Rowan pointed out to General Bradley that the seven chemical mortar battalions bore no logical numerical relation to the number of armies and corps on the list, that they could not be distributed equitably,

[459]

and that they were far too few to achieve their full potential. Rowan then asked Bradley for the twenty-four mortar battalions of the original troop list. Bradley replied that he would like to have more mortar units but, because the troop ceiling had just about been reached, adding them would mean giving up other units that were equally valuable. This he was reluctant to do.

At the time of these negotiations the only mortar battalion located in the European theater was the 81st. Attempts to secure one of the four combat-experienced units from the North Africa Theater of Operations were turned down as "impossible and impracticable"; the mortar battalions in Italy already were overworked. Colonel Shadle, chief chemical officer of that theater, stated that the battalions were so highly regarded that "the sticking of my fingers into this question would be practically the same as putting them in a 'bandsaw'."2

A change in the table of organization for the mortar battalion promised an unexpected source of men. Under the existing table the authorized strength was 1,010; a revised table of September 1943 reduced this number to 622.3 Colonel Rowan was informed that the battalions in the United States were organized under the older table. Taking into consideration the battalions then existing and those which could be formed from the men excess by reorganization under the new table, Colonel Rowan came up with a total of eleven potentially available battalions. If General Bradley asked for but one battalion in addition to the War Department troop list, there would be enough to equal just half of the original request, or one per corps and army. General Bradley acceded, requesting twelve mortar battalions for the theater troop list.

Although it began auspiciously, the plan for capitalizing on battalion reorganization as a source for new units soon turned sour. The theater received permission in December to activate a mortar battalion in England manned in large part by the men freed in the reorganization of the 81st Battalion.4 But Rowan learned to his dismay that the battalions in the United States earmarked for his theater had already been reorganized under the new table of organization, thus cutting off an important supply of personnel.

With only two battalions in England as late as February 1944 the

[460]

shortage of such units became critical. Although the troop basis for the ETO now included 12 battalions, only 7 were listed as available in 1944. What was worse, only 4 of these would be in the theater in time for the Normandy landings-the 81st, the 92d, activated in England, and the 86th and 87th, both of which arrived in April.5

Preparations for OVERLORD

Of these four battalions the 92d was least prepared for combat operations in France. The other three units concentrated on amphibious training in the winter and spring of 1944, having undergone basic and unit training in the United States. The 92d, activated in England in February 1944, had to start from scratch.6

From the beginning the training activities of the battalion were hampered by the type of men it received. Of the first 373 assigned to the unit, 308 were of average intelligence or less. Fifty-six had AWOL records, 22 had been court-martialed for other offenses, and 12 had had VD. About 15 of the group were suffering from some disability or were on limited service; 13 others went immediately to the hospital. Throughout its period of activation the 92d usually received those men declared surplus by other units.7

The battalion devoted the last two weeks of February to making its camp at least partially fit for human habitation. The first part of March saw the enlisted men screened for a selection of potential NCO material and subjected to a review of all basic subjects. Small arms instruction, mortar drill, and the training of 162 drivers followed. By the end of March companies had been organized, squads knew something about their mortars, and the battalion was able to pack and move with some degree of order. Training intensified in April, with special emphasis on field work and marksmanship. Morale reached its lowest point at this time; few realized that the rigorous conditioning was necessary for their own survival. Work on mortar ranges began on 10 April and continued into May. The month of

[461]

May also saw the battalion undergo a two-and-a-half-week period of intensive training while attached to a field artillery group. There was no time for amphibious training before the invasion, and as a consequence the 92d did not participate in the initial landings. Nor did the 86th Battalion receive assault training in time for D-day activity.

The 81st Battalion was the chemical unit most adequately prepared for the D-day operation. It had trained at the amphibious center at Camp Gordon Johnston, Fla., before leaving the United States. From December 1943 until the following April it participated in intensive exercises at the Assault Training Center in Devonshire and in other maneuvers along the western and southern coasts of England. The 87th Battalion was also well prepared for the invasion; thoroughly trained in the United States, it took part in two amphibious exercises in England that spring. The latter training had indicated that the increased problems in communications and supply in amphibious operations made greater demands on unit personnel. (Battalion commanders already were finding that the reduced complement of men in the new TOE was inadequate to keep forty-eight mortars in action even in normal operations.) Consequently, each of the two mortar battalions earmarked for the invasion was temporarily fattened by 125-man detachments from two chemical processing companies.

The Normandy Campaign

The 81st and 87th Chemical Mortar Battalions landed in Normandy early on D-day in support of the V and VII Corps, respectively, on OMAHA and UTAH Beaches. Companies A and C of the 81st were attached to battalions of the 16th Infantry, 1st Division, and Companies B and D landed with battalions of the 116th Infantry, 29th Division. As it approached the shore, the landing craft carrying the forward battalion group received heavy shelling which killed a sergeant and seriously wounded the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Thomas H. James. Without benefit of engine or rudder the craft drifted aimlessly until currents providentially beached it at a protected spot along the shore.

Company A, landing at H plus 50, lost some of its equipment in the heavy seas. Even worse, Capt. Thomas P. Moundres, its commander, was mortally wounded before reaching the beach. The senior lieutenant assumed command and succeeded in getting the platoons into firing

[462]

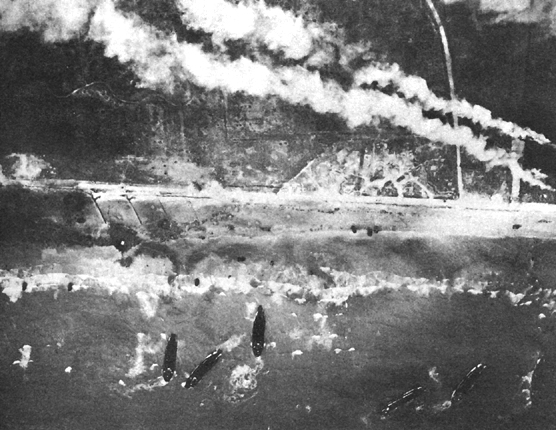

SMOKE SCREEN DURING THE OMAHA BEACH LANDINGS

positions. First day missions included a smoke screen for advancing infantry and the destruction of an enemy machine gun. Company C did not land until midafternoon because the infantrymen in preceding waves were pinned down on the edge of the beach. The unit finally got ashore at 1500 and made its way to positions about 200 yards inland. It received no requests for supporting fire.

The four LCVP's carrying Company B were unable to find a route through the heavy obstacles in their assigned sector, and two of these vessels were disabled by artillery fire as they headed toward another landing area. Despite a heavy sea and enemy opposition, all troops and equipment aboard the stricken craft were transferred to an empty LCT. Company D landed between H Plus 50 and H plus 60, but its commander, Capt. Philip J. Gaffney, was killed when his landing craft struck a mine. Before finding an outlet off the dangerous strip of beach the unit changed its position three times and fired one mission. Night found the mortars dug in at St. Laurent-sur-Mer. Thus, on 6 June

[463]

CHEMICAL MORTARS AT UTAH BEACH

1944 3 officers of the 81st were killed and 2 others, including the battalion commander, were seriously wounded. One company lost its total complement of transportation while each of the other three companies lost two vehicles.

Trouble developed on D plus 1 as enemy snipers allowed leading infantry elements to pass through, firing on units which followed. To meet this threat the battalion formed details to wipe out the sniper nests. The mortarmen learned another trick of combat during these early days in Normandy. The enemy, having retreated from the area in which American mortars were to be set up, had marked on its firing charts all logical positions for these weapons. The men of the 81st soon found it was best to avoid reverse slopes and similar accepted mortar sites in favor of unconventional open terrain.

The 87th Chemical Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. James H. Batte, was attached to VII Corps in the D-day assault of UTAH Beach. Three of the firing companies supported the three battalions of the

[464]

8th Infantry, 4th Division, and the fourth company supported a battalion of the 22d Infantry of the same division. Forward observers of the mortar companies landed with the initial waves of infantry, and the units themselves came in at H plus 50. Shortly after landing, the battalion fired 140 rounds and then followed the infantry in moving off the beach. For almost six hours the 4.2-inch mortars were the only ground weapons capable of delivering heavy fire support.8 Targets during the first twenty-four hours of action were enemy machine gun emplacements, concrete emplacements, and pillboxes.

Quinville Ridge, some ten miles northwest of UTAH Beach and a D-day objective for VII Corps, was not taken until 14 June. The companies of the 87th Battalion supported the 4th Division in the fight for this objective, expending 16,870 rounds and suffering 36 casualties in the process. The mortar units continued in support of the 4th Division as it drove north to Cherbourg. On 23 June Company C fired a spectacular rolling barrage in support of a battalion attack which prompted Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt to telephone his congratulations back to the mortar positions.9

The attack on Cherbourg included several other noteworthy 4.2-inch mortar missions. On 23 June Company A blended its fire so that white phosphorus showered German troops just routed from their positions by high explosives. That evening twenty men from Company D fought as infantry troops while the rest of the unit delivered heavy fire against an enemy counterattack. On 24 June the mortars of Company B successfully dueled with German artillery, assumed to be 88-mm. guns, which had been shelling an American regimental command post. On the same day, Company C aided in repelling a vigorous enemy counterattack by getting off 300 rounds before the division artillery could come into action. Expressing his view that the two mortar companies with his division had materially aided the success of the advance, Col. Kramer Thomas, chief of staff of the 79th Division, emphasized an inherent characteristic of the mortars-that of quick response to a given mission. On several occasions, he stated, the chemical mortars, because of the rapidity with which they went into action and the availability of ammunition at gun positions, were the only artillery-type support available.10

[465]

After the fall of the port of Cherbourg half of the battalion supported the 9th Division during the several days required to mop up the Cap de la Hague. By 1 July, when this operation ended, the 87th Battalion had been in continuous combat for twenty-five days. Nineteen men had been killed and 75 had been wounded; battalion ammunition expenditures totaled 19,129 rounds of HE and 11,899 rounds of white phosphorus.

The nature of the fighting in Normandy was determined by the predominant feature of the Norman terrain, the hedgerow. As described by Colonel MacArthur, Chemical Officer, 12th Army Group: "The country is gently rolling grazing land, consisting of rectangular grass fields generally about 100 yards deep in the direction of our advance and 150 to 200 yards wide." The colonel stated that these hedgerows were actually earth walls about four feet high surmounted with bushes and dotted with small trees. They were natural obstacles which could be put to excellent use in warfare, and the enemy fully exploited their defensive possibilities. Machine gun emplacements were located at the corners of hedgerows, and their lengths bristled with machine pistols, rifles, and antitank weapons. Mines with trip wires sometimes supplemented the already imposing defenses. Naturally, an advance over this ground was as slow as it was dangerous; units measured their progress by hedgerows, not miles. This was a form of position warfare with bocage replacing the traditional role of trenches.11

The terrain was particularly dangerous for mortar forward observers, a fact emphasized by the following notation from the journal of the 87th Battalion for 13 July 1944: "Scarcely a day passes that some one, if not all the forward observer party, are either wounded or killed. Yet, all officers of this battalion operate as forward observers and there are always volunteers among the men."

The 86th Battalion arrived in Normandy on 29 June. Attached to First Army, the companies of this unit initially supported elements of the 90th Infantry and 82d Airborne Divisions. Company B was an exception. The ship which was taking this unit across the Channel sank after either striking a mine or being struck by a torpedo. One man was listed as missing and 26 were injured; most of the equipment was lost. Refitted in England, the unit rejoined the 86th on 18 July.

[466]

Although created for combat support, chemical mortar battalions found themselves at times in something other than a supporting role. The experience of Company A of the 86th on the night of 6-7 July is a case in point. One of its platoons was firing for a battalion of the 359th Infantry; another was in the immediate vicinity. Wire connected the mortar company with the infantry battalion. The mortar company liaison officer at the forward infantry observation post reported that the situation there was uncertain and appeared to be getting out of control. An urgent mission, requested by an adjacent battalion, prompted the mortar company commander to withdraw his security element and send it for more ammunition. Although three infantry companies were thought to be in front of the mortars, enemy machine gun fire suddenly pierced the air above the mortar crews. The mortar company commander called the infantry battalion but could get no definite word about the situation. The infantry battalion agreed that a mortar barrage would probably help, and the two platoons fired at a range of 700 yards. When the machine gun fire crept closer, the commander again tried to contact the infantry command post. Finding it had moved, he ordered one of his platoons to withdraw, a maneuver accomplished with difficulty because of the heat of the barrels and the firm emplacement of the base plates. Soon the mortar positions were swept by enemy machine gun fire and the other platoon received the march order. As the company withdrew, 5 men fell into enemy hands, escaping when the Germans were driven off by the company's sole remaining .50-caliber machine gun. The next morning all equipment was recovered with the exception of one destroyed jeep.12

Although not involved in D-day operations, the 92d Chemical Battalion soon participated in the Normandy fighting. Attached to XIX Corps and supporting the 30th Division, the unit first saw action in the opening days of July along the Vire River. On 8 July the 92d supported the 29th Division which was spearheading the XIX Corps drive on the centers of German resistance around St. Lô. This and one other attack proved unsuccessful; fourteen days and two attachments later the battalion was poised for the breakthrough operation.

COBRA, the offensive to break out of Normandy, began on 25 July. The VII Corps, with three divisions abreast, led the attack. Companies A and B, 92d Battalion, were firing preparatory missions in support

[567]

of units of the 30th Division when Allied heavy bombers droned in to soften German resistance. To the dismay of the American troops, about 35 of the planes dropped their bomb loads within friendly lines.13 Nearly 200 bombs fell in the 92d Battalion area alone. Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, Army Ground Forces commander, was instantly killed while observing the action from a point just in front of Company A. Battalion losses were 5 dead and 23 wounded. Company A lost 9 mortars, half of its ammunition, and all of its vehicles. Company B fared better, managing to salvage 8 of its 12 mortars. On the following day Company C relieved Company A and the latter unit drew back to reorganize; three days later Company A, in turn, relieved Company B. By 3 August all units returned to the battalion area for rest and refitting.

Operational Problems

Despite the complaints heard throughout the Normandy Campaign about the lack of trained mortar battalion replacements, there was no over-all shortage of CWS officers in the European theater. Colonel St. John, Chemical Adviser, G-3, SHAEF, reported in June 1944 that so many CWS officers were in the theater that they were "sitting in each other's laps and standing on each other's feet."14

The root of the trouble was the existence of two distinct types of CWS officers, technical and combat, whose roles were usually not interchangeable. Misassignment not only resulted in a waste of talent but usually in a substandard performance. An officer whose training and background fitted him for a chemical laboratory assignment probably made a poor mortar platoon leader. Because these facts were understood neither by the Ground Forces Replacement Command in England, nor by the personnel officers of the higher commands, it was not unusual for trained mortar officers to find themselves in depots or in branch immaterial positions, while the mortar battalions had to settle for unqualified replacements.15

This situation was verified by the commander of one of the mortar units which saw action in Normandy. Colonel Batte reported that during the course of one week in the latter part of June he received

[468]

two CWS officers and one infantry officer as battalion replacements. Batte stated: "The two CWS officers admitted they had never so much as touched a mortar in their entire army experience; before entering OCS they were in the Medical Corps. The greater part of their service in CWS after finishing OCS had been in pools and at the Military Police Training Center, Ft. Custer, Mich."16 The accuracy of these comments made by graduates of the CWS officer candidate school might be open to question, since the OCS curriculum included fifty hours Of 4.2-inch mortar training.17 But whatever the explanation, these men were not psychologically prepared to enter combat.18

They probably lacked technical proficiency, as well, for the Chemical Warfare School came to consider fifty hours as an inadequate period of mortar training, and in the summer of 1943 inaugurated a Battalion Officers Course, with the specific purpose of producing qualified mortar battalion officers. Because the battalions in combat were not receiving these officers as replacements, Colonel Batte had been requesting and usually getting infantrymen.19 Similar problems were encountered with enlisted men. Lt. Col. William B. Hamilton, commanding the 86th Battalion, stated that the replacements received by his unit were not trained CWS mortarmen but were "basics from the infantry or most any other branch."20

Efforts were made to overcome the lack of suitable mortar battalion replacements. General Rowan established a Chemical Training Battalion in England which began operations in August 1944 Until its termination in October 1944 this unit, which doubled as a replacement organization, trained 125 officers and 100 enlisted men for assignment with mortar battalions. This fine record was in part vitiated by two factors: the heavy demands permitted only a fraction of these troops to receive all of the prescribed three weeks of training, and despite

[469]

all precautions these men continued to become lost in the Ground Forces Replacement Command.21

The personnel situation remained critical throughout the winter of 1944-45. December found the mortar battalions in the 12th Army Group understrength by twenty-five officers and the theater replacement center seemingly devoid of qualified chemical mortar officers.22 The 92d Battalion, earlier unaffected by replacement problems, now reported that "trained officer and enlisted replacements have been unavailable and consequently a continuous training program has been found necessary."23

An urgent message from the theater to the War Department in February 1945 called attention to the need for chemical mortar officers. Within the theater further steps were taken to rectify the replacement situation. All CWS officers assigned outside the service had been located and a number of them were now serving in their proper capacities. Also, the willingness of the Ground Forces Replacement Command to work with the informal advice of General Rowan's office lessened greatly the chance of misassignment of officers.24

A personnel problem of a different sort had existed even before the battalions entered combat. The revised table of organization of September 1943, it will be recalled, reduced the battalion strength from 1,010 to 622. Battalion commanders were of the opinion that this number was below that required to man, supply, and provide communications for the forty-eight mortars within the unit. Although there was disagreement as to the composition of an appropriate table of organization, all of the commanders considered the 6-man squad too small to keep a mortar in action. A popular remedy was to withdraw several mortars and reinforce the remaining squads with the men thus freed. Lt. Col. Ronald LeV. Martin took more drastic measures with the 92d Battalion. He received permission to eliminate one of the four companies of his unit, thus anticipating the revised

[470]

table of organization which was to become effective in the fall of 1944.25

Another difficulty which emerged in Normandy involved the tactical employment of chemical mortar units, or more precisely, the matter of mortar battalion control. The resulting controversy provoked two schools of thought, one holding that mortar units should be directly responsible to the infantry which they supported, the other maintaining that they should operate under artillery control. Influential in this dispute was the background and training of the participants. The commander of the 92d, for example, had been a field artillery officer until transferring to the CWS; moreover, the last training phase of his unit had been supervised by the artillery officer of the corps to which the battalion was attached. It was not strange that this battalion commander became a leading exponent of the artillery control school.

One of the main benefits of the artillery control system was the efficiency with which the battalion could operate as a unit. In defensive situations mortar fire could be readily massed, and the unit's fire could be effectively integrated with that of the artillery. In the European theater, however, the limited number of mortar battalions generally precluded the maintenance of battalion integrity.26

Most of those concerned, CWS and otherwise, favored the close infantry support method. This fact was confirmed in a CWS theater of operations letter which stated that although applicable artillery techniques and practices should be used, the normal role of the chemical battalion "should be considered as part of the Infantry team . . . furnishing close support with a heavy and powerful mortar."27

.....

[471]