CHAPTER VI Preparations for Invasion Medics in Britain performed their many and complex BOLERO tasks as preliminaries to their principal and most urgent mission: support of the amphibious assault on continental Europe. In the early period of the buildup, planning and preparation for that assault engaged the attention of only a few members of the chief surgeon's staff. Then, as 1943 gave way to 1944, the pace of assault planning intensified. Medical personnel of all ranks and in all units were swept up in invasion preparations. By late spring of 1944 ETO medics, like everyone else in the theater, were tensely awaiting the rapidly approaching D-Day. Early Planning Efforts Medical planning for a cross-Channel assault started in April 1942, after tentative approval of the American ROUNDUP invasion concept, and ran concurrently with the BOLERO buildup. The British and U.S. ground, naval, and air commands in London set up, among other committees on the ROUNDUP operation, an administrative planning staff to deal with logistical matters. The staff, in turn, was divided into lettered sections specializing in particular aspects of logistics. Section C, which did most of the medical planning, included members of the British War Office, Admiralty, Air Ministry, Combined Operations Staff, and Ministry of Health, with the theater chief surgeon and, more often, Colonel Spruit, Hawley's London representative, speaking for the American forces.1 Section C, in common with the other logistics planning groups, worked within uncertain parameters. By mid June the ROUNDUP tactical planners had developed a general concept for simultaneous landings on a front stretching from the Pas-de-Calais to Cherbourg, with perhaps six divisions in the initial assault; beyond that the outlines of the operation remained unclear, clouded with doubt as to its feasibility. At the same time Section C had little amphibious warfare experience to guide it. The US Navy and Marine Corps before the war had outlined a tentative amphibious doctrine, also adopted by the Army, but the resulting manuals had little useful to say about medical [149] operations. Wartime British Commando raids, and even the August 1942 attack on Dieppe, offered few medical lessons but confirmed that heavy casualties were to be expected. In the face of these uncertainties and areas of ignorance, Hawley, Spruit, and their British colleagues plowed ahead as best they could.2 From the start of their deliberations the medical planners confronted a problem that would remain a central preoccupation until D-Day: treatment and evacuation of the anticipated many casualties of the first days of the invasion. The dilemma was simple. The assault force would suffer its largest proportion of wounded at precisely the time when the fewest medical troops would be on shore to care for them. Section C, on the basis of informed guesswork, assumed that there would be 22,500 Allied wounded, almost half of them stretcher cases, during the first two days of ROUNDUP. Hawley, Spruit, and their British counterparts quickly ruled out any attempt to treat these injured on the French shore (designated in plans as the "far shore" to distinguish it from the British "nearshore"), concluding that treatment would require more medics, hospitals, and equipment than could possibly be landed in the assault and early buildup and more space than would be available in the crowded beachhead. If the wounded were not to be cared for on the far shore, they would have to be evacuated directly from the beaches to hospitals in Great Britain, but evacuated in what? Few British and no United States hospital ships were available in the theater, and in any event these large oceangoing vessels could embark patients conveniently only at ports. Besides, such scarce ships should not be risked under enemy air attack and shore battery fire. The British had developed a smaller type of hospital ship, the hospital carrier. Converted from shallowdraft coastal steamers, these vessels, each able to accommodate 100 litter and 150 ambulatory patients, could lie close to the beaches and load by means of water ambulances-motor boats carried on board the mother craft. Hospital carriers, however, also were vulnerable to hostile air and artillery and they took hours to fill to capacity. The four that would be available in England in late 1942 could not begin to evacuate all the expected casualties. Tactical landing craft that returned to England after unloading obviously were the only means for taking many wounded off the beaches quickly, although the types of such craft in service during ROUNDUP planning were small and not well adapted to handling men on stretchers. Nevertheless, in late 1942, for lack of any real alternative, the ROUNDUP administrative planning staff, at Section C's recommendation, established in principle a policy of maximum evacuation during the initial assault and use of returning landing craft as the main [150]

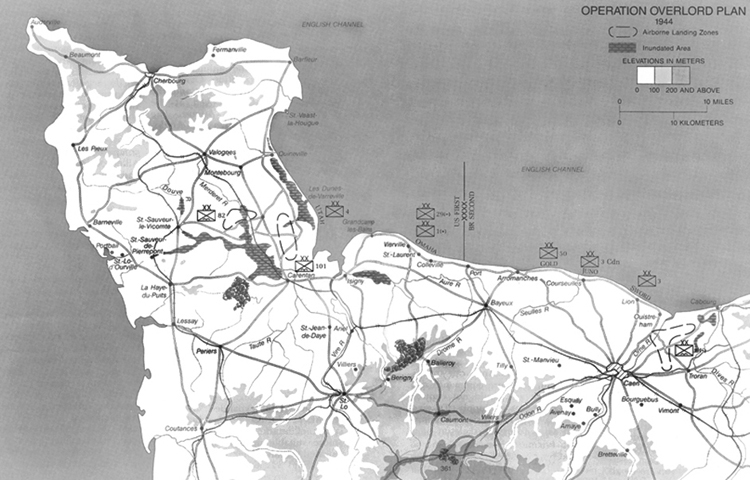

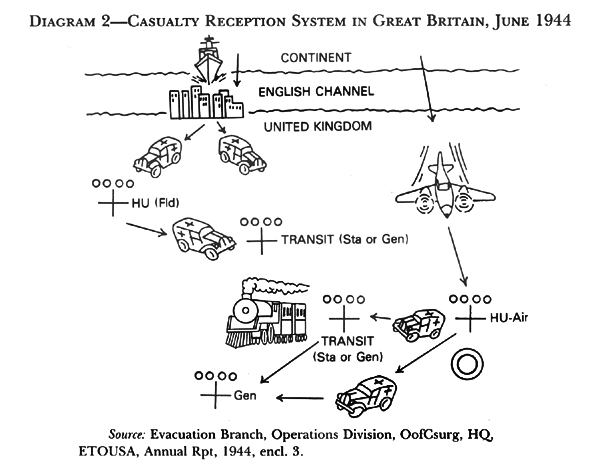

BRITISH HOSPITAL CARRIER NAUSHON, a converted American ferryboat casualty carrier. What types of landing craft to employ for this purpose, how many could be made available for medical use (indeed, how many would be available at all), and whether any could be earmarked exclusively for evacuation and protected by the Red Cross-these facts the committee could not determine. The principle it adopted, however, would remain in force throughout the rest of the lengthy invasion planning process.3 Besides struggling with the problem of beachhead evacuation, the ROUNDUP medical planners arrived at basic decisions on a number of other important questions. They established an army-navy division of cross-Channel evacuation responsibilities that applied to both British and American forces. Under it, the armies were to collect all wounded on the far shore and move them to the beaches; the navies would load evacuation craft and care for patients on the voyage to England; the armies then would have charge of unloading the wounded and removing them to hospitals. General Hawley, Colonel Grow of the Eighth Air Force, and British medical and RAF authorities agreed on similar plans for air evacuation from the Continent to the United Kingdom. [151] The ground forces and Services of Supply were to collect evacuees at French airstrips for pickup by transport planes returning to England. Air Force medical personnel were to care for the patients in flight, and the Services of Supply would deplane them in Britain and transfer them to hospitals. For their own forces the American planners began outlining the complicated sequence in which field army and then SOS medical units would land in France. They also roughed out a system for receiving water-evacuated casualties in England, using field hospitals and clearing stations at the ports for triage and emergency surgery and distributing transportable patients at once to selected hospitals inland.4 Medical invasion planning, in this period of limited theater resources, at times took on an air of unreality. During July, for example, in a last effort to avoid the diversion to North Africa, General Marshall ordered the European Theater and Services of Supply to report on the feasibility of launching a small-scale cross-Channel attack, code-named SLEDGEHAMMER, on 15 September. Hawley, in response, informed General Lee that, if the buildup continued at its present pace, the medical service would be short 8,900 beds and 8,616 officers and men on the projected attack date and would have no hospital train units, ambulance battalions, or boats for water evacuation. Pressed by Lee to report positively on how he could support the operation, the chief surgeon reiterated his previous assessment, with the qualification that he would be able to support the landing if he could borrow field medical units, hospitals, and equipment from the British, who, of course, had none to spare. Reports such as this helped scuttle SLEDGEHAMMER and ROUNDUP and paved the way for the commitment to TORCH.5 Cross-Channel assault planning of all sorts came to a stop in late 1942, as TORCH plans and preparations monopolized the attention of British and American staffs. Yet the ROUNDUP studies and conclusions-preserved in memoranda, data books, and individual memories-would constitute a starting point for the next round of invasion planning. Many of the principles and concepts of operation first sketchily outlined in ROUNDUP would be the foundation of the much more elaborate plans to follow.6 OVERLORD: The Planning Process The decision of the Allied leaders at Casablanca, in January 1943, to revive the cross-Channel attack project for execution sometime in 1944 set in motion a lengthy, complex planning process. It began with a small Anglo-American staff, eventually drew in most British and American headquarters, and ended in the final test of strength in the west with Nazi Germany. In March 1943, to give organizational substance to the Casablanca [152] decision, the Combined Chiefs of Staff established the Anglo-American staff known as COSSAC to plan the invasion and superintend preparations for it. Under the guidance of British Lt. Gen. Sir Frederick E. Morgan, COSSAC drafted the outline plan for the invasion, Operation OVERLORD, which Roosevelt, Churchill, and the Combined Chiefs approved at the Quebec conference in August. The Allies then put together the Anglo-American combined ground, naval, and air headquarters that were to fill in the details of OVERLORD and undertake its execution. In mid January 1944 the arrival of General Eisenhower in London and the activation of SHAEF around the nucleus of COSSAC capped the invasion command structure. Eisenhower, after refining and expanding the COSSAC plan, set 1 June as the attack date. To obtain more landing craft for the enlarged assault, the Combined Chiefs canceled the originally contemplated simultaneous landing in southern France. On 1 February SHAEF published its outline plan for NEPTUNE, the code-name for 1944 operations within OVERLORD. SHAEF's ground, naval, and air headquarters followed with their outline plans and various national forces then got to work on the details of tactics and logistics. The final plan, developed by COSSAC and expanded upon by SHAEF, selected Normandy as the point of attack because it possessed more suitable invasion beaches, was located within easier reach of major ports, and was less strongly defended than the previously favored Pas-de-Calais. In contrast to the broad front contemplated for ROUNDUP, the OVERLORD plan called for a single concentrated amphibious assault. Three British Commonwealth and two American divisions were to land north and northwest of Caen, with one of the American divisions going in on the east coast of the Cotentin Peninsula to gain position for a drive on the key port of Cherbourg. Three airborne divisions-one British and two American-were to drop to secure the flanks of the beachhead and open routes inland. This force, and follow-up troops, was to secure a compact lodgement area in which the Allies could mass men and supplies and from which they could advance methodically, first to capture additional Norman and Breton ports, then to clear the region between the Seine and the Loire, and finally to take Paris and go on to the Rhine, in the process destroying as much of the German Army as possible (see Map 4).7 With the formation of COSSAC, medical support planning paralleled every stage of OVERLORD'S development. The COSSAC medical section began work in June 1943, under Chief Medical Officer Lt.Col.G.M.Denning Lt. Col. G. M. Denning of the Royal Army Medical Corps. Besides Denning, the small, informal section included a Royal Navy representative and Lt. Col. Thomas J. Hartford, MC, Hawley's executive officer. In September, after Hartford went to 21 Army Group to keep in touch with ground forces medical planning, Lt. Col. John K. Davis, MC, from the ETO Hospitalization Division, assumed the [153] MAP 4 [154-155]

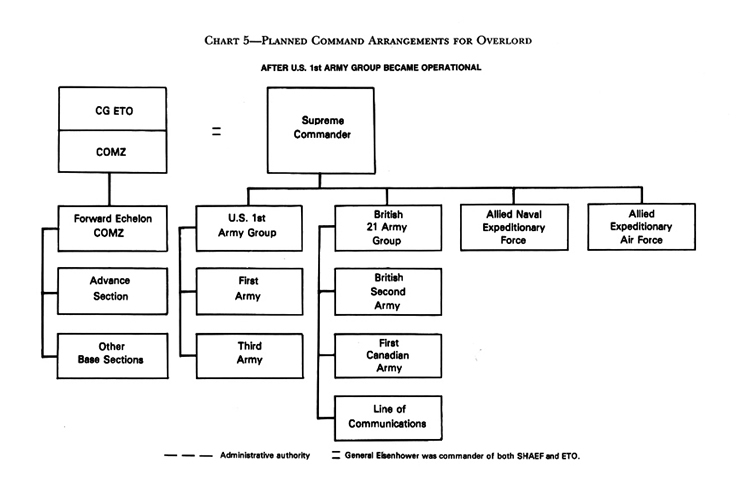

COL. THOMAS J. HARTFORD COSSAC post. Denning and Davis remained in the medical section when it became part of SHAEF, with General Kenner as chief medical officer. The section stayed small under Kenner, never including more than four officers, evenly divided between British and Americans. Under both COSSAC and SHAEF, the medical section made no comprehensive plans for supporting the invasion. Instead, it drafted administrative directives on certain inter-Allied and interservice problems. The section established, for example, uniform casualty-estimation formulas for use by all Allied planners, and it set basic evacuation policy and decided upon the principal means for cross-Channel transport of wounded. As part of SHAEF the section reviewed and reconciled the proliferating plans of subordinate headquarters. Most COSSAC and SHAEF medical decisions in fact represented a consensus between the chiefs of the British and American medical services, reached at frequent formal and informal conferences. Throughout the invasion planning the American medics at COSSAC and SHAEF drew upon General Hawley's office for advice and information, with the staff preparing most of their studies and position papers.8 Detailed American medical planning for NEPTUNE, covering the invasion and the first ninety days of the battle for France, began early in February 1944, after publication of the SHAEF outline plans. Planning took place within a complex logistics organization created to accommodate national control of supply to overall British direction of NEPTUNE ground operations. General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery's 21 Army Group functioned as both tactical and administrative ground force headquarters for the invasion. Subordinate to it, the US 1st Army Group and First Army had logistical, as well as tactical, responsibility for the American troops under them, but these commands did not represent and could not control the ETO Services of Supply. To give the latter a voice in invasion planning, as well as to form the skeleton of a [156] continental logistics system, General Eisenhower, as ETO commander, early in February activated two new headquarters: Advance Section, Communications Zone (ADSEC), and Forward Echelon, Communications Zone (FECOMZ). Each of these new headquarters possessed immediate planning and future operational functions. The Advance Section was attached to the First Army, which had charge of all tactical planning for the American part of the amphibious assault and also did logistics planning for the first fifteen day on shore. Besides assisting with army planning, ADSEC worked out the details of SOS operations for the period from the sixteenth through the fortieth day after D-Day (D+16 through D+40). The Forward Echelon, at the outset an element of 21 Army Group headquarters, supervised ADSEC planning and itself made SOS plans for D+41 through D+90. Operationally, ADSEC was to act as the supply element of the First Army until D+15, organizing the beach behind the advancing troops. From D+15 through D+40, after the army established its rear boundary, ADSEC would constitute the communications zone under the supervision of 21 Army Group, exercised through the Forward Echelon. FECOMZ itself was to become active on D+41, when a second US army went into operation and the 1st Army Group, hitherto subordinate to 21 Army Group, became a separate command directly under SHAEF (see Chart 5). The Forward Echelon then would take command of the entire American support area behind the armies (whether under the US army group or coordinate with it was never entirely settled). ADSEC at this point was to revert to the status of a movable base section under FECOMZ. The section would follow close behind the armies and link them to the Services of Supply, relinquishing supply activities nearer the shore to other base sections that would be formed as the campaign progressed. Around D+90 SHAEF and ETOUSA were expected to move to France, whereupon FECOMZ would merge back into the ETO-SOS headquarters and General Lee, as Eisenhower's deputy for logistics, would assume direct control of all elements of the Services of Supply-to be redesignated the Communications Zone (COMZ).9 Under this administrative arrangement the First Army surgeon, Colonel Rogers, and his staff, working closely with the surgeons of the two assault corps, the V and VII, drew up medical support plans for the initial landing and the first two weeks of combat. The ADSEC surgeon, Col. Charles H. Beasley, MC, and the FECOMZ surgeon, Colonel Spruit, prepared plans for establishing the medical portion of the continental Communications [157]

CHART 5 [158]

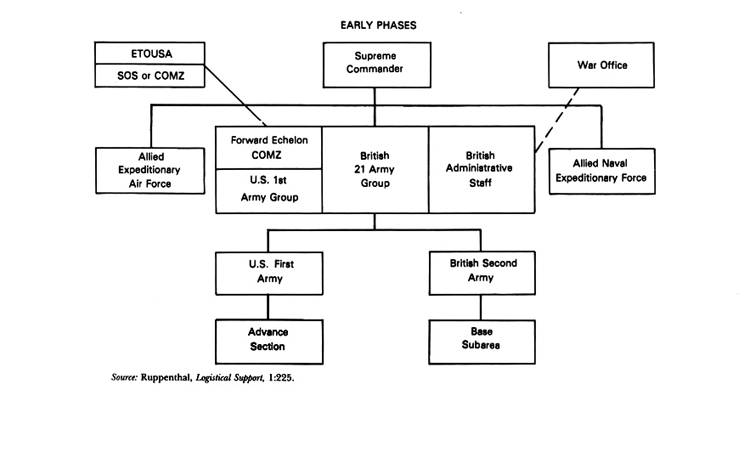

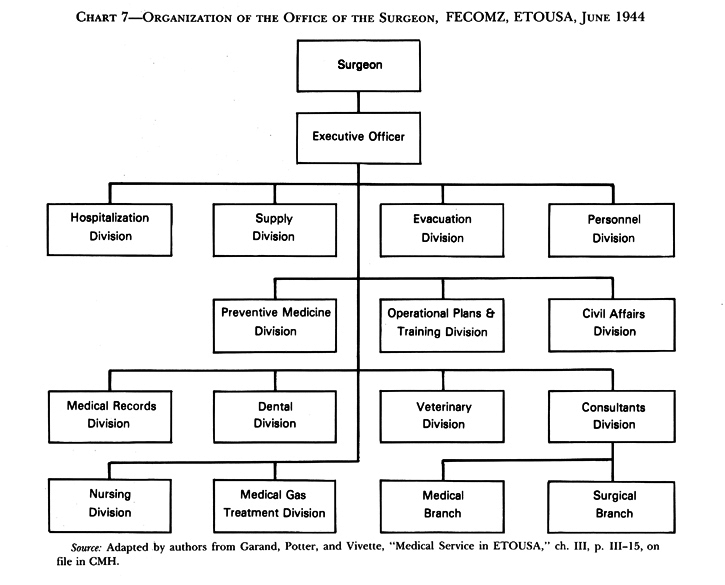

CHART 5 cont. [159] Zone. Roger's First Army medical section had come over from the United States with its parent headquarters and had been in operation in London and Bristol since October 1943, but the ADSEC and FECOMZ surgeons' staffs had to be improvised in haste (see Charts 6 and 7). Of substantial size-the ADSEC surgeon's office eventually included forty-three officers and fifty-six enlisted men-these organizations drew manpower from casuals, base section headquarters, and General Hawley's office. Colonel Beasley, for example, had been surgeon of the Eastern Base Section; his deputy, Col. James B. Mason, MC, had served as Hawley's chief of operations; and Colonel Spruit had come over to FECOMZ from running the Cheltenham branch of the chief surgeon's establishment. Each of the COMZ surgeons organized his office into divisions paralleling those under the chief surgeon. Spruit's office, indeed, was for practical purposes an advance echelon of Hawley's.10 While the First Army, ADSEC, and FECOMZ surgeons drafted the NEPTUNE plans, many of the decisions incorporated in them came from other headquarters. General Hawley, charged with supervising all theater medical planning, took part in establishing most major policies. His staff furnished information to the army and COMZ surgeons and wrote key portions of their plans, including, for instance, the basic army-navy agreement on division of cross-Channel evacuation responsibility. Hawley's office published its own standard operating procedure for medical service on the Continent and oversaw base section planning for support of the embarking invasion forces and for receiving casualties from the far shore. At SHAEF General Kenner kept in close touch with ETO medical planning and intervened in selected aspects of it. Of the higher-level ETO surgeons, Colonel Gorby of the 1st Army Group, in accord with the group's inactive role at this stage, had the least to do with NEPTUNE planning. He confined himself to keeping informed of First Army activities, assembling the medical portion of the troop buildup schedule, and participating in SHAEF medical policy discussions.11 The NEPTUNE medical planners made use of the data collected by their ROUNDUP predecessors and adopted many principles worked out for the projected earlier invasion. They also availed themselves of the medical lessons learned in amphibious operations in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. The Fifth Army late in 1943 assembled many of these lessons into [160] a manual for amphibious medical support, upon which the ETO planners drew extensively. Besides using the manual and other written reports, some ETO medical officers visited the neighboring theater for firsthand observation and conferences with army and SOS surgeons. During the early 1944 planning period, Colonel Hartford of 21 Army Group, Colonel Davis of SHAEF, Colonel Beasley of ADSEC, and Colonel Darnall of Hawley's Hospitalization Division made Mediterranean tours. Their visits, besides affording a change of climate, produced useful information. Hartford, for example, confirmed from Fifth Army experience the practicability of evacuating wounded over the beaches early in amphibious assault and brought back up-to-date estimates of whole blood transfusion requirements in combat surgery.12 NEPTUNE medical planning extended over about four months, with the First Army plan appearing in late February and those of ADSEC and FECOMZ respectively on 30 April and 14 May. These plans, while published separately, issued from a seamless process of discussion and negotiation so complex as to defy narration. The three principal medical planning staffs worked in constant consultation with each other, with nonmedical planners at their own headquarters, and with the surgeons' staffs of higher- and lower-command echelons. They kept in close touch with Navy and Air Force medical staffs and with those of their British colleagues. The ADSEC medical section had British officers attached to it for planning. In the end, as a result of this method of working, the evolution of each plan was shaped by the evolution of each of the others. Together, the major medical plans constituted a comprehensive blueprint for the NEPTUNE campaign.13 The NEPTUNE Campaign The NEPTUNE plans covered the development of a continental medical service from the time the first wave of infantry hit the beaches through the securing of the French lodgement area. Essentially, the plans addressed two problems: provision of support for a strongly opposed amphibious landing, and development of an army and then a COMZ medical establishment-all to be done from a crowded British base, across a narrow but [161]

CHART 6 [162]

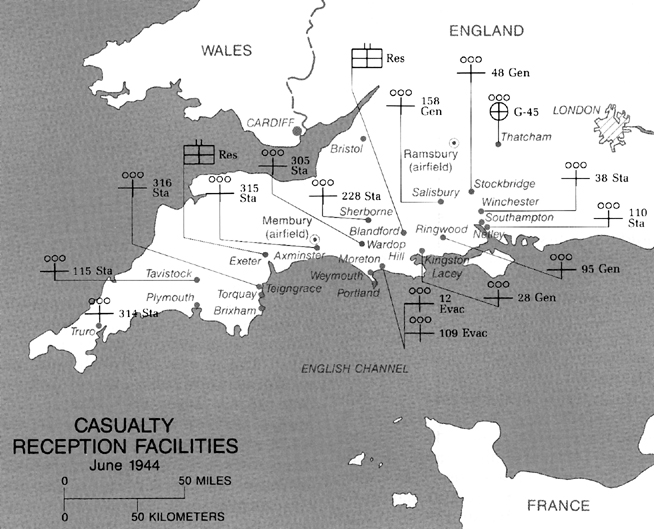

CHART 7 [163] treacherous body of water, with limited shipping and port facilities.14 Support for the initial attack from the sea required the most complex arrangements and caused the planners the most controversy and soul-searching. The First Army tactical plan was straightforward. On D-Day the V Corps, with elements of the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions, was to go ashore on the army's left on OMAHA beach, a stretch of Normandy coast backed by low bluffs northwest of Bayeaux. The VII Corps, with the 4th Infantry Division, was to land on the right on UTAH beach, near the base of the eastern side of the Cotentin Peninsula. The 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions, also under VII Corps, were to drop before the main attack, to secure crossings over the flooded areas immediately behind UTAH. Logistical support for the seaborne forces was to come from engineer special brigades-two, forming a provisional brigade group, for OMAHA and one for UTAH. These brigades were to begin landing soon after the first infantry elements. Assisted by shore party battalions of Rear Adm. Alan G. Kirk's Western Naval Task Force, which was responsible for transporting, landing, and supporting the American invasion troops, the special brigades would clear the beaches of wreckage, mines, and obstacles; open roads; and establish supply dumps. Their medical battalions would set up the first nondivisional medical facilities on the far shore.15 For medical support planners the number of casualties to be expected on and immediately after D-Day was the first crucial consideration. On this point COSSAC and SHAEF for a long time could not obtain agreement among the concerned staffs, although all expected losses to be very heavy. Different headquarters held to various estimates until February 1944, when General Kenner assembled the chief medical officers of the major invasion commands to reach a common figure "to establish our position for General Eisenhower." The conferees, after much debate, decided to assume for planning purposes that the assault force would suffer 12 percent wounded on D-Day and 6.5 percent on D+1 and D+2, with a declining proportion thereafter. Using this ratio, First Army surgeons had to think in terms of treating or evacuating over 7,200 wounded on D-Day and another 7,800 in the next forty-eight hours, of whom about 3 percent-at least 450-would be too severely injured to [164] be transported any distance without definitive surgery. Even these estimates, the planners realized, were uncertain. Kenner noted: "If gas should be used, then these figures go by the board."16 On the basis of these estimates COSSAC, SHAEF, and army planners confronted the same problem of care and evacuation during the first days of the invasion that had preoccupied their ROUNDUP predecessors. COSSAC early reaffirmed the ROUNDUP decision to evacuate from the beaches to England all but the most lightly wounded and, conversely, those needing immediate surgery to keep them alive. COSSAC also reiterated the ROUNDUP staffs conclusion that most casualties must go out in returning landing craft. Unlike the earlier planners, those at COSSAC and SHAEF had available a vessel suited to their requirements: the LST (landing ship, tank), which had come into service since the end of ROUNDUP. This 330-foot oceangoing craft, designed to disembark tanks and other heavy vehicles directly onto a beach, also could embark large numbers of casualties in a comparatively short time through its bow doors and ramp, which could accommodate ambulances, litter-carrying jeeps, and a newly introduced amphibian truck, the DUKW. The latter vehicle also could swim out to and board an LST offshore. Within the ship the cavernous tank deck, extending the width and most of the length of the LST, could hold up to 300 litters, either fastened to bulkhead racks or lashed to the deck surface. When not transferred from vehicles directly onto the tank deck, casualties could be hoisted on board in small craft or on individual stretchers. The ship's upper decks and crew's quarters could hold 300 additional walking wounded. Any LST could be fitted for evacuation, and could accommodate a small emergency surgical facility, without reducing its ability to perform its main task of landing combat vehicles. On 16 July 1943, at a conference attended by General Hawley and General Hood, the British Army medical chief, COSSAC adopted the LST as its principal evacuation craft. Reinforcing this decision, General Marshall directed in October that all cross-Channel movement of American wounded "will be handled in properly equipped combat LST[s]."17 The US Navy, which had charge of providing LSTs for the invasion, agreed to modify for casualty carrying 83 of the 98 ships allocated to the American forces and 70 of the 113 assigned to the British. After he became SHAEF's chief medical officer, General Kenner endorsed these arrangements. He directed medical planners to assume that only 75 litter and 75 [165]

LSTS READYING FOR THE INVASION walking patients would be moved on each voyage of an LST, to allow for the fact that few ships would be able to stay near the beach long enough to load to full capacity. If practicable, of course, the vessels were to take on more than this minimum. To provide emergency surgery for casualties taken on board directly from clearing stations during the first days of the attack, the Western Naval Task Force surgeon, Capt. George B. Dowling, MC, planned to put two medical officers and twenty hospital corpsmen on each of his task force's LSTS. Because few of these Navy medical officers were experienced surgeons, General Hawley agreed to reinforce each LST medical complement with an Army surgical team of one officer and two enlisted technicians. To place still more emergency surgery capacity near the beaches, Kenner assigned 5 hospital carriers each to the British and American forces. These ships were to carry additional medical personnel and supplies to France and then embark patients requiring extensive early surgery.18 [166] COSSAC and SHAEF based their evacuation plans on the LST reluctantly and in the face of much doubt about the feasibility of the whole system for removing wounded from the beaches. The doubters included General Hood. After inspecting an LST at Portsmouth, Hood called the vessel a "cold, dirty trap" for injured men. He carried unavailing protests against its use all the way to Churchill's War Cabinet. Colonel Cutler considered LSTs "rotten ships for care of wounded American boys," an opinion shared by many of his colleagues. The objectors had reason for concern. When emptied of their vehicular cargoes, LSTs rolled deeply in all but the calmest seas, creating, to say the least, an unstable platform for surgery. With any kind of sea running, DUKWs could not swim out to an LST and negotiate its ramp. Most important, as combatant vessels carrying troops and weapons outward bound, LSTs could not be protected with the Red Cross and were legitimate attack targets. If one foundered for any reason, the litter patients on board inevitably would go down with it. Kenner and Hawley shared their colleagues' uneasiness about the LST, Kenner calling use of the vessels "an improvised method of removing casualties forced upon the Medical Service by operational necessity." Nevertheless, they had to override all objections to employment of the LST, for it was the only available means of large-scale cross-Channel evacuation. They took comfort from the fact that LSTs had performed well in evacuation in the Pacific and could only hope that weather severe enough to prevent the loading of wounded on LSTs also would prevent the entire invasion.19 Until D-Day Allied medical planners considered their evacuation system a fragile structure, dependent for success on many uncontrollable variables. Kenner, in particular, feared that a "back-log" of unevacuated, untreated wounded would accumulate on the beaches, with demoralizing impact on the combat troops. He warned:

[167]

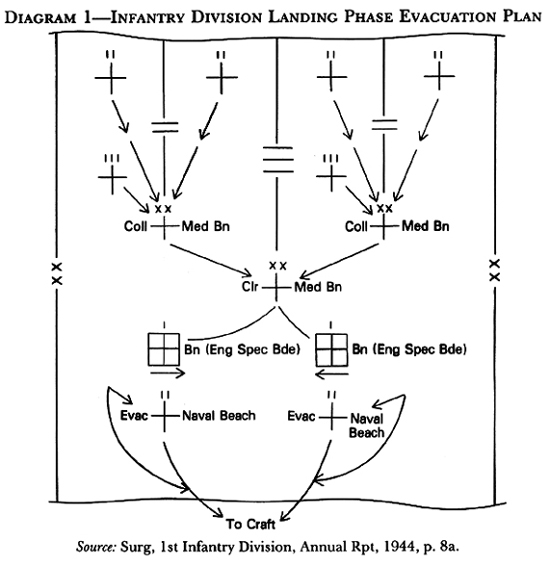

Colonel Rogers and his staff built their First Army medical support plans around the basic COSSAC-SHAEF evacuation decisions and attempted to provide against a breakdown of seaward evacuation. To this end Colonel Rogers arranged to reinforce each assault division medical battalion with an additional collecting company, to be landed as soon as possible after D-Day, and to attach six teams from the army's auxiliary surgical group to the clearing company of each engineer special brigade medical battalion. So augmented, these units-the only hospitals on shore during the first twenty-four hours or so of combat-would be able to care for a substantial number of severely wounded. On D-Day company aidmen and battalion medical sections were to go in with the first infantry waves, followed in close sequence by Navy shore party medical sections (one officer and eight hospital corpsmen per army battalion), division collecting companies, the engineer special brigade medical battalions, and the division clearing companies. This interlacing of division and special brigade elements, based on Mediterranean practice, would permit the division medical service to move inland at once and begin regular operations, leaving the shore party and special brigade medical units, in static beach positions, to collect wounded who fell in the first attack, to evacuate division medical installations, to set up emergency surgical hospitals, and to load all movable casualties on LSTs and other landing craft (Diagram 1). The beach medical elements also were to evacuate and support the airborne divisions, as soon as the seaborne forces made contact with them. Until then the airborne medical companies, landing by parachute or glider with attached surgical teams soon after the infantry touched down, would collect and treat all paratrooper wounded.21 After the assault and the securing of the beachhead, American reinforcements were to pour in, over OMAHA and UTAH beaches and later through Cherbourg and other captured ports, bringing US strength on the Continent to over 1 million by D+90. The First Army and 1st Army Group before D-Day established a consolidated movement schedule for this buildup, detailing the size and shipping requirements of each unit, its date and place of embarkation, and its destination and assignment on the far shore. They divided each day's sealift among ground, air, and service forces so as to maintain a balanced flow of combat and support elements. Medical units were interspersed throughout the schedule, on the basis of priorities developed by the First Army, ADSEC, and FECOMZ surgeons and worked into the troop list after tortuous negotiations with all the other forces vying for space (see Table 3). The First Army's nondivisional medical units were to go in [168]

DIAGRAM 1 first, between D-Day and D+15, with field hospitals, auxiliary surgical teams, and the corps medical battalions leading. Evacuation hospitals were to follow, beginning on D+5, along with army medical battalions (separate) and groups, a supply depot company, a convalescent hospital, a laboratory unit, and a gas treatment battalion. A few ADSEC units were to be interspersed with those of the First Army, but most would arrive after D+12. The first scheduled to come were additional ambulance companies and evacuation and field hospitals, intended to function as station hospitals and holding units. On or about D+15 the first general hospital in France, the 298th, was to disembark and go into operation in Cherbourg. By D+90 both the Advance Section and Forward Echelon expected to have twenty-five general hospitals on the Continent, at preassigned locations in Normandy and Brittany, besides a full complement of supply depots and other COMZ medical units.22 Medical supplies in large quantities were to start arriving on the beaches as soon as the troops did. All First Army combat and support units landing [169] TABLE 3-PLANNED LANDING OF MEDICAL UNITS, 6-14 JUNE 1944

on D-Day and the following 3 days were to carry reserves of rapidly consumable items, in the hands and on the backs of soldiers and loaded into vehicles. Each infantry, artillery, chemical warfare, engineer, and ranger battalion; each divisional collecting and clearing company; and each engineer special brigade medical battalion was to receive a special allowance of dressings, small implements, drugs, morphine, and dried plasma packed in waterproof containers portable by a single man. Each organization also would bring ashore extra litters, field medical chests, splints, and blankets. In the Advance Section mobile hospitals were to embark with reserves of expendable supplies sufficient for 10 days of operations; other medical units were to carry 3-day reserves. Medical maintenance supplies were to be shipped automatically from the United Kingdom during the first 90 days of continental operations. Before D-Day the First Army, Advance Section, and Forward Echelon submitted requisitions to the chief surgeon's Supply Division for their periods of primary logistical responsibility, with allowances calculated to replace lost and consumed matériel and to establish 14- or 21-day reserves (depending on the echelon and the class of supplies) in army and COMZ depots by D+90. The supplies so requested were to be packed before the assault and loaded on ships on a daily schedule as the buildup proceeded. From D-Day until about D+40 most maintenance supplies would consist of special division assault surgical and medical units, designed by the First Army and assembled by the Supply Division. Each of these units included dressings, drugs, and equipment for treating 500 casualties and was divided into 100-pound waterproof packages for easy, safe movement and storage. To ensure arrival [170] of enough supplies on the beaches while the casualty rate was highest, the Supply Division based its scheduled shipments of these units on estimated numbers of wounded, rather than on total troop strength, as was the practice with regular medical maintenance units (which were not adapted to the assault situation in any case). As the buildup continued, standard 10,000-men-for-30-days maintenance units were to supplant the special ones. When enough depot companies reached France, the armies and the Communications Zone were to establish regular distribution procedures, with division medical supply officers drawing on army depots that those of the Advance Section would replenish. Whole blood, biologicals, and penicillin were to reach the front through special channels, delivered by the theater blood service.23 Hospitalization and evacuation in France were to evolve as the manpower and supply buildups progressed, with the aim throughout being to retain as many patients as possible on the Continent. From D-Day until about D+ 18 the First Army was to send back to England all sick and wounded except nontransportables (defined as men with severe abdominal, chest, and head injuries and compound fractures) and casualties who could be treated and returned to duty from division facilities. As First Army hospitals went into operation, the forces in France, at the army commander's direction, were to shift to a 7-day evacuation policy. Once COMZ fixed hospitals became available, the Advance Section was to evacuate to them from the armies casualties returnable to duty within 15 days, to be extended progressively to 30 days as still more hospitals arrived. Soldiers needing longer hospitalization, or eligible for return to the United States under the 180-day theater policy, were to go directly from army installations to hospitals in England. Following the principles established by COSSAC, the NEPTUNE plans called for evacuation of wounded over the beaches during and after the assault, and for their transportation to Britain in LSTs and, after the first day or so, in hospital carriers. When the Allies captured and reopened Cherbourg, the Americans were to use that port, in addition to the beaches, for evacuation to the United Kingdom. US hospital ships, eleven of which were expected to reach the European Theater between 29 May and 12 August, also would load wounded at Cherbourg for direct evacuation to the United States. Air evacuation to Britain, from both the field armies and the Communications Zone, was to begin as soon as the ground forces secured airstrips usable by the C-47s of the IX Troop Carrier Command. For overland movement of patients, the NEPTUNE plans provided for improvisation of hospital trains from captured rolling stock, but the armies and COMZ were to rely primarily on ambulances and, in emergencies, on trucks and jeeps, until about D+56. At that time hospital trains constructed in England were expected to begin [171] rolling off ships at ports and beaches.24 The NEPTUNE planners concerned themselves with keeping the troops on the Continent healthy, as well as with treating them when sick and injured. Army and COMZ preventive medicine plans, based on information collected and collated by the chief surgeon's Medical Intelligence Branch, assessed the state of public health in occupied France and listed the likely major disease threats on the Continent. Troop commanders in France, the plans warned, could expect to find an ill-nourished, dirty civilian population whose hospitals and public health agencies were operating inefficiently because the occupying Germans had stripped them of much equipment and personnel. French water purification and sewage disposal facilities, never the best, could be assumed to have broken down under administrative neglect and combat damage. Compared to what the Army faced in the Mediterranean, the Southwest Pacific, and other non-European tropical theaters, disease in northwestern Europe posed hardly any threat to the conduct of operations. Epidemic louse-borne typhus, which the planners considered likely to be introduced from eastern Europe by German troops and slave laborers, loomed as the disease of most potential danger. Commanders and surgeons also would have to guard against typhoid, but such familiar diseases of troops in the field as dysentery, diarrhea, influenza, venereal diseases, and infectious hepatitis, as well as a variety of skin ailments and vermin infestations, were likely to constitute the campaign's principal medical problems. Even though American troops had already been immunized against typhus, the field armies and the Communications Zone planned to issue insecticide powder to their troops and prepared for mass inspection and delousing of soldiers, civilians, and prisoners of war. NEPTUNE plans for combating other diseases depended on the standard immunizations, personal hygiene, mass sanitation, water treatment, sewage disposal, and pest eradication procedures, as well as on special supervision of soldier eating habits to prevent vitamin deficiencies among men subsisting for long periods on C- and K-rations.25 Preventive medicine planners expected venereal diseases, the incidence of which reportedly had increased threefold in France since 1941, to constitute "one of the most difficult control problems to be encountered." First Army and COMZ plans, backed up by a theater circular drafted by Colonel Gordon's Preventive Medicine Division in cooperation with the senior medical consultants [172] and command venereal disease control officers, prescribed essentially the same precautions tested and proven in the United Kingdom: troop education, provision of healthful recreation, widespread issue of condoms and V-Packettes (even embarking assault troops were to be offered them), establishment of prophylactic stations, and-as far as language and local law and custom permitted-tracing of contacts. Repression of prostitution received special emphasis. In contrast to the unorganized, barely tolerated character of the business in Great Britain, continental prostitution was an accepted, legally regulated and sanctioned social institution, featuring numerous brothels. War Department policy, confirmed by practical experience in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy, ruled out any official Army attempt to license and regulate such establishments. Hence, ETO preventive medicine officers and medical consultants inserted in NEPTUNE plans and the theater circular a strongly worded policy statement:

The NEPTUNE medical planners sought to anticipate and outline a solution for every foreseeable actual or potential problem. To keep seasickness from taking the fight out of the assault troops before they went ashore, the First Army prepared to issue newly developed antimotion sickness capsules-ten of them to be taken on a fixed schedule-to each embarking soldier, even though tests of the remedy in amphibious exercises had produced at best inconclusive results. Medical precautions against the threat of German gas attacks included intensive training for all troops in first aid for chemical warfare casualties and the issue of eye ointments and impregnated protective clothing. The various medical plans set policies and procedures for treating civilian sick and injured in Army hospitals (to be done only when necessary to save life), caring for and processing Allied casaulties in the American evacuation chain, treating and evacuating wounded prisoners of war, and disposing of captured medical supplies. In detail and comprehensiveness the medical plans matched those for other aspects of NEPTUNE. They also shared in the essential rigidity of the overall plan, based as it was on the assumption that Allied forces would push the Germans back at a fairly steady pace. A radical slowdown or a radical acceleration of Allied progress would require complicated, difficult adjustments [173]

GAS DECONTAMINATION

EQUIPMENT, stockpiled at Thatcham supply

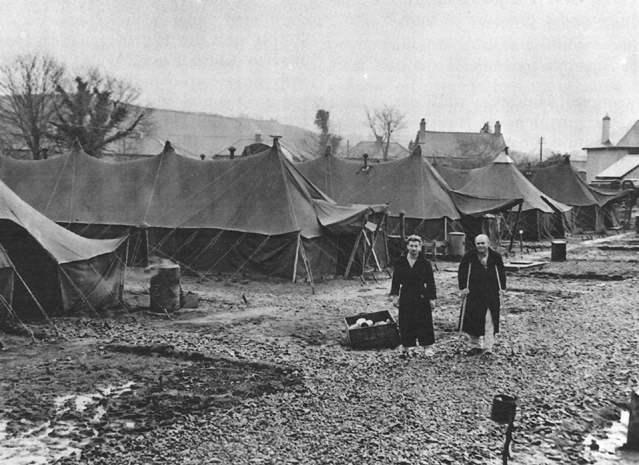

depot as a precaution against throughout the elaborate medical support system.27 Technical Aspects Even before the OVERLORD and NEPTUNE plans took definite shape, General Hawley and his staff began searching for solutions to a variety of technical problems connected with the invasion. The chief surgeon and his assistants paid special attention to three problems: providing whole blood to forward medical units, drafting guidelines for combat zone surgical practice, and devising a system for sheltering fixed hospitals on the Continent. The Blood Program US Army surgeons in the European Theater learned from British experience in the Western Desert, and from early American operations in North Africa and Sicily, that whole blood-while highly perishable and difficult to store and transport-was indispensable for controlling shock in severely wounded soldiers. Blood, administered as far forward as possible in the evacuation chain, saved lives [174] that plasma alone could not. In response to this growing weight of evidence General Hawley in July 1943 decided to establish an ETO whole blood service, modeled on the highly successful British Army Transfusion Service. The American blood bank took shape during late 1943 and early 1944, planned and supervised by an ad hoc committee headed by Colonel Mason, then chief of the Operations Division, and including Colonels Cutler and Middleton, the commander of the 1st Medical General Laboratory, and the chief of the Supply Division. No T/O blood bank unit existed, so General Hawley improvised one. He reorganized the 250-bed 152d Station Hospital into a base depot, located at the 1st Medical General Laboratory at Salisbury, and mobile advance depots-two for the Communications Zone and two for the armies. The base depot was to collect type O blood (the only kind used) from volunteer SOS donors, process it, and prepare it for daily shipment to France, where the advance depots, using truck-mounted refrigerators, would distribute it as far forward as the field hospital platoons attached to division clearing stations. Equipment for the units came from the United States, under a special project for continental operations (PROCO), and from the British, who furnished indispensable refrigerators, as well as bottles, tubing, and needles for bleeding and transfusion. By mid-April 1944 the blood bank, under the overall command of the 1st Medical General Laboratory and with Maj. Robert C. Hardin, MC, in immediate charge as executive officer, had secured most of its equipment and finished organizing and training the 11 officers and 143 enlisted men of its base, COMZ, and army depots. General Hawley meanwhile secured from the theater top priority for shipments of blood to France and from the Ninth Air Force a guarantee of daily space on aircraft.28 As the invasion approached, the ETO blood service faced a prospective supply shortage. Since whole blood could be stored for a maximum of fourteen days, the theater required a reliable flow of new blood about equal to the expected usage rate in the field, a rate which Colonel Mason's committee, applying the British planning ratio of 1 pint of blood for each 8-10 wounded, estimated as averaging about 200 pints per day during the first three months of combat. This amount was safely within the ETO blood bank's 600 pints-per-day collection and processing capacity. Even as the bank prepared for operations, however, the medical service, on the basis of reports from the Fifth Army in Italy, increased its estimate of requirements to 1 pint for every 2.2 casualties. [175] On this basis the blood bank, working at full capacity, would not be able to keep up with daily demands, and it became apparent that, even if collection and processing could be increased, the supply of raw material in the theater could not. When General Lee issued the planned call for volunteer donors early in 1944, response from the Services of Supply was disappointing. By mid-April the base sections, in spite of exhortations from Lee and Hawley, had enrolled only 35,000 of 80,000 potential type O donors. As early as May 1943 Colonel Cutler and Major Hardin had suggested flying in blood from the United States, but Surgeon General Kirk, until well after D-Day, vetoed this proposal. His staff underestimated the need for whole blood in field surgery and doubted the feasibility of transporting the perishable substance across the ocean. From the available donors the ETO blood bank, by starting collection well in advance and storing blood up to the maximum safe limit, could meet immediate invasion requirements. But, as the campaign expanded and the limited SOS donor pool diminished with the movement of service troops to France, the blood supply at some point would fall short of need unless the theater could find an additional source. On D-Day, such a source still was not in sight.29 The Surgical Program The effort of General Hawley and his consultants to define uniform surgical practice for each step in the evacuation process had more satisfactory and definite results. During 1942 Colonel Cutler and the surgical consultants began rewriting War Department Technical Manual 8-210, Guides to Therapy for Medical Officers, to simplify it and make it more useful to surgeons in the field. Finished late in 1943, the resulting ETO Manual of Therapy, published as a pocket-sized booklet, reached medical officers before D-Day Of the manual's three sections, two dealt with surgery in clearing stations and evacuation and fixed hospitals. Written in short, simple sentences, these sections concentrated on specific treatment of particular types of injury at each point in the evacuation chain and omitted lengthy expositions of theory. Generally, the manual emphasized the need to avoid definitive surgery in the forward areas, unless absolutely necessary to save life. The third section of the manual covered basic medical emergencies, from poisoning to neuropsychiatric disabilities. This manual, supplemented on 15 May 1944 by an ETO circular on "Principles of Surgical Management in the Care of Battle Casualties," which reiterated many of the same policies, constituted a concise practical guide for surgeons fresh from civilian practice and usually inexperienced at [176] treating severe injuries in primitive facilities under pressure of time.30 The Expeditionary Hospital General Hawley's staff early took up the problem of housing general and station hospitals on the Continent, where they had to assume that the battle would leave behind few readily usable buildings. In late 1943, after almost a year of work, the Hospitalization Division and the ETO Office of the Chief of Engineers completed draft plans for an expeditionary tented-hutted hospital. Designed to house a 1,000-bed general or 750-bed station hospital, this standardized installation was to consist initially of tents on concrete bases, on a site improved with paved roads and with water, sewer, and power lines. Each tent was to have space beside it for a parallel hut, which the Engineers were to erect during hospital operations as circumstances permitted. Passing through several stages of development, from completely tented to completely hutted, an expeditionary hospital was supposed to be able to accommodate its full capacity of patients at each stage, even as construction and the transfer of facilities from under canvas to under roofs went on. In October 1943, to test the newly completed plan, the Services of Supply sent the 12th Evacuation Hospital to Carmarthen, Wales, to erect and operate an expeditionary 750-bed station hospital serving troops in that area. The unit, and an Engineer company, arrived on the site, deliberately selected for unsuitability, early in November. In spite of rain, snow, obstructing hedgerows, and poorly drained marshy ground, the hospital unit and its supporting engineers had the plant in tented operation before the end of the year. The hospital was well into the hutted stage in March 1944, when the 12th turned it over to a station hospital unit. In March the Hospitalization Division issued a manual with construction specifications for the expeditionary hospital, incorporating lessons learned at Carmarthen. The system proved its worth even before the invasion, as the Services of Supply used it to set up several temporary plants needed to increase fixed bed capacity or receive casualties from France.31 Readying Medical Supply As invasion planning neared completion, General Hawley viewed with increasing alarm one key element of his establishment: medical supply. Throughout the renewed BOLERO [177]

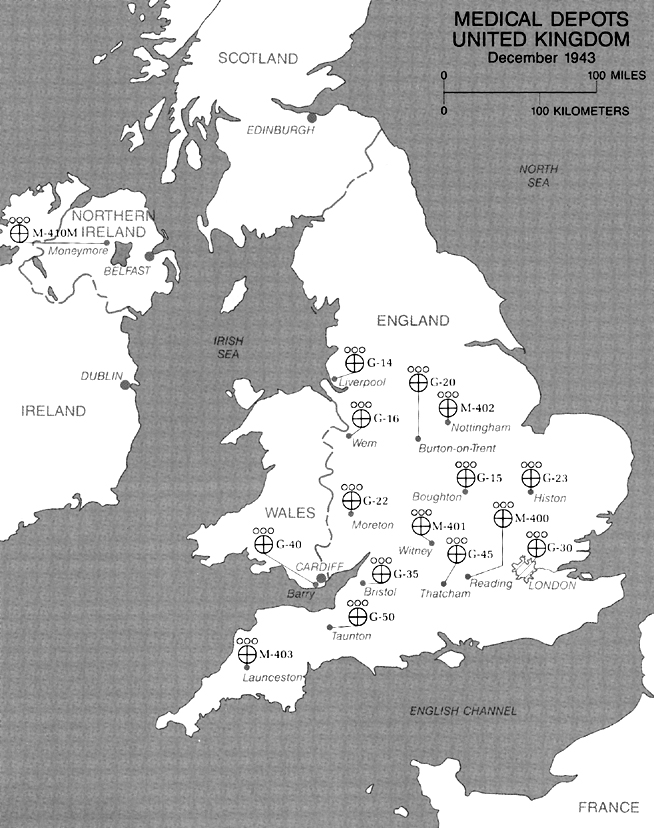

EXPEDITIONARY HOSPITAL AT CARMARTHEN buildup persistent shortages and administrative deficiencies had made it difficult for the supply service even to support the troops in Britain. The Supply Division of the chief surgeon's office lacked qualified manpower and leadership to meet its expanding responsibilities, and the flow of matériel from American and British sources encountered diversions and dams at many points. By early 1944 both General Hawley and Surgeon General Kirk had been forced to realize that, unless drastically reorganized and reinforced, the medical supply service would fail in its effort to support the coming offensive. The Supply Division during 1942 had been the weakest element in ETO medical administration; it improved only marginally in 1943. In March Col. Walter L. Perry, MC, arrived to take over the division, replacing the third in a series of unsatisfactory chiefs. General Hawley welcomed Perry, whom the surgeon general had picked for the position and who was experienced in depot operations, and gave him a free hand in reorganizing the supply system. Perry, however, like his predecessors, found the job too much for him. Most of his difficulties stemmed from a lack of trained men. Although his Cheltenham staff doubled during the year, [178] from 8 to 16 officers and from 13 to 47 enlisted men, the size of the task grew even more rapidly, and few of the additional personnel possessed the specialized training needed to manage what was, in effect, a home base rather than a field supply service. Perry also lacked direct access to General Hawley after the latter moved to London in May. Instead, the supply chief had to communicate through Colonel Spruit, the deputy chief surgeon at Cheltenham, a circumstance which reduced Perry's ability to call attention to his requirements. Repeated Supply Division requests for more staff, for example, never went beyond Spruit's office.32 Manpower deficiencies plagued the theater's medical supply depots (see Map 5). Between the beginning of 1943 and early 1944 the number of medical branch depots and medical sections of Quartermaster general depots increased from five to sixteen. Eight of these depots issued supplies to units and hospitals in their geographical areas; the others held reserve stocks or performed specialized functions, such as outfitting tactical units, receiving British supplies, and repairing medical equipment. Of the 90 officers and 1,200 enlisted men who staffed these installations, about half were members of six field depot companies, units which arrived or were activated in the theater during the last half of 1943; the rest were on temporary assignment from replacement centers. Neither the depot companies, which were organized for mobile field operations, nor the attached casuals had received any training in the operation of large permanent depots. They learned their jobs by doing them. All were on temporary assignment-the depot companies awaiting orders for field service and the casuals subject to transfer on short notice. Without a sense of permanency and, in the case of the attached men, with no promotion prospects, these troops suffered from low morale and had little incentive to excel at their often hard, demanding work.33 Depot operations were inefficient at best and chaotic at worst. An officer who joined the medical section of Depot G-35 at Bristol early in 1944 reported: "There was no depot organization-it seemed as [if] everyone was doing what he chose to do. Responsibilities were not defined." Each depot commander improvised his own system for filling requisitions and his as [179]

MAP 5 [180] own stock control procedure. In most depots, record-keeping fell behind issues, leaving both local commanders and the Supply Division unaware of developing shortages until the shelves were empty. The Supply Division required periodic reports from the depots of stores on hand; but the depots' poor record-keeping rendered this information suspect, and the Cheltenham office lacked the staff and tabulating equipment to prepare up-to-date theater-wide reports on stock levels and distribution. With incomplete and outdated information, the Supply Division could not shift matériel between depots to even out local shortages and surpluses. The more enterprising depot commanders developed their own contacts for this purpose. Medical units and hospitals, in spite of instructions to the contrary, went from one depot to another until they secured not only the items they needed but also reserves considerably over authorized allowances. These field improvisations enabled the medical service to get along from day to day, but the resulting lack of accurate information disrupted theater-wide supply planning and hindered General Hawley in dealing with his sources of medical supply in Britain and the United States.34 During 1943, as American war production reached full momentum and the shipping shortage eased, the European Theater drew an increasing proportion of medical items, as well as other types of supply, from the United States. Small at the beginning of the year, the flow of matériel grew with the accelerating BOLERO buildup, but it by no means went smoothly. General Hawley complained throughout the year about delayed or only partly filled requisitions, while the surgeon general's office and the Port of New York insisted that they were meeting all ETO requirements. The stock control deficiencies in Hawley's depots contributed much to these disagreements, both by preventing timely dispatch of requisitions to the United States and by making it difficult to ascertain exactly what supplies actually had arrived.35 Shipment of preassembled and packed table-of-equipment (T/E) outfits for hospitals and field medical units continued to be trouble, plagued,, in spite of War Department and ETO efforts to improve the system and in spite of the abandonment by the New York Port of Embarkation of the practice of earmarking particular outfits for individual organizations. Delivery of assemblies, instead of keeping pace with unit arrivals in Britain, fell behind. ETO depots then had to deplete their stocks to outfit disembarking units, [181] with no assurance of early replenishment. Furthermore, most medical unit assemblies-especially those for hospitals-reached British depots short 15-30 percent of their components, in spite of strenuous efforts by the New York port to have them carefully marked and loaded on one ship. After much mutual recrimination between Hawley and the surgeon general's office, an investigation early in 1944 disclosed that most assemblies were entering English ports intact but that the Supply Division had made no special arrangements for keeping them together as they were unloaded. As a result, portions of hospitals and unit outfits turned up in different depots. These depots, uninstructed in handling this matériel, simply added it to their general stock without informing the Supply Division.36 Although shipments from the United States increased, the medical service during 1943 procured more than half of its supplies, by tonnage, from Great Britain. British matériel, in fact, comprised 49 percent of all the goods received by the medical service between mid-1942 and mid-1944 These supplies included most hospital furniture and housekeeping equipment, as well as quantities of over 900 other items, among them surgical instruments and many drugs. British procurement had been invaluable in meeting TORCH requirements and in tiding the medical service over its period of low priorities and limited support from the United States, but it possessed many unsatisfactory aspects. The British insisted that the Americans place very large long-term orders far in advance of deliveries, a procedure that made it all but impossible to adjust procurement to changing requirements. At the same time British deliveries on these contracts were irregular in both timing and quantity. Few quality controls existed. In the emergency of 1942 General Hawley had disregarded American specifications in accepting British supplies. He used whatever his consultants, after examining samples, declared would serve the purpose. These items underwent no inspection as they came off the production lines; shipments reaching American units frequently were poorly packed, substandard in quality, or in unusable condition. Even when British matériel arrived in good condition, US Army medical people were unaccustomed to its differences from their own and considered many items inferior to their American equivalents. Seemingly small differences in design and markings took getting used to, and at least one cost lives. British-supplied carbon dioxide, used in anesthesia, came in tanks painted green, the color used in the United States to denote oxygen. The resulting mixups caused at least eight deaths on operating tables before the Professional Services Division issued [182] warnings and arranged for relabeling of tanks.37 In August 1943 General Hawley began trying to reduce his dependency on the British. Aware of deficiencies in quality and slow deliveries, he also had discovered that his allies, while furnishing inferior goods to the European Theater, simultaneously were obtaining large quantities of standard American medical supplies and equipment from the United States under Lend-Lease. At Hawley's urging, Surgeon General Kirk authorized the theater chief surgeon to cancel contracts with the British for items duplicating lend-lease shipments and to requisition them directly from the New York Port of Embarkation. The War Department, at the same time, instructed the medical and other supply services to stop buying from the British a long list of items now overstocked in the United States. In spite of orders from Hawley, however, the Supply Division and Its London procurement office, through poor coordination, made no real attempt to reduce local purchases. Instead, the procurement office placed large orders for British goods to be delivered in the first half of 1944.38 During the last few months of 1943, as more and more troops poured into the British Isles and invasion preparations got under way, the Supply Division obviously began to buckle under its steadily increasing work load. Disembarking units and newly opened hospitals waited for weeks for their basic equipment. The Air Force, to Hawley's embarrassment in his fight against an autonomous air medical service, continued to complain of shortages of field chests and other vital articles; the flight surgeons continued to resort, successfully, to their own channels to remedy these deficiencies. Early in 1944 the fixed hospitals in the Southern Base Section, where most American troops were concentrated, had only 75 percent of their authorized equipment. In response to complaints from all quarters, Hawley pressed the Supply Division for information but received only incomplete, inconsistent, or inaccurate replies. At the same time the tone of his correspondence with the surgeon general's office grew increasingly testy, as each side blamed the other for shortages and delays. On 7 December Hawley told General Kirk: "I have had a Hell of a lot of trouble with supply and am still having [183] trouble. . . . Frankly, I am worried about my medical supply when I think of the approach of active operations."39 Hawley had reason to worry. His Supply Division barely was meeting the routine requirements of the forces stationed in the United Kingdom. With much delay and inefficiency it was equipping newly landed units and recently completed hospitals, the pressures of the latter task being eased by British construction delays. Additional missions to be accomplished in early 1944 promised to swamp the floundering division. Within about five months ETO medical depots would have to assemble and place on site equipment for all the hospitals still to be opened before D-Day This entailed building thirty outfits for 1,000-bed general hospitals and twenty for 750-bed station hospitals, but the most efficient depot in late 1943 took three months to put together 60 percent of one 1,000-bed assembly. As if this were not enough, the depots would have to outfit still more incoming units, complete the equipment of organizations taking part in the assault, and pack dozens of waterproof maintenance units to supply the invasion force in its first weeks on shore. With the existing organization, personnel, and methods, these jobs could not be done in time.40 Fortunately for General Hawley, assistance was on the way. Late in 1943 Surgeon General Kirk, responding to the chief surgeon's repeated cries for help in supply, and at the suggestion of Colonel Gorby-then in Washington preparing to join Hawley's staff decided to send a group of experts from his office to survey the ETO supply service and recommend comprehensive remedies. In doing so Kirk acted outside the established chain of command, which made the theater chief surgeon responsible only to the theater commander. The surgeon general's delegation would possess little authority beyond the moral force of its collective expertise. To lead the group, Kirk appointed the chief of his Control Division, Col. Tracy S. Voorhees, JAGD, a lawyer who had become well versed in medical organization and supply. Voorhees picked the other team members: Lt. Col. Bryan C. T. Fenton, MC; Lt. Col. Leonard H. Beers, MAC; and Mr. Herman C. Hangen, a civilian consultant to the surgeon general. All these men possessed extensive knowledge of medical supply distribution and depot operations; all earlier had helped reorganize the supply system in the United States.41 [184]

COL. TRACY S. VOORHEES Voorhees and his party left Washington by plane on 24 January 1944, all but Beers (who was to join the European Theater to direct stock control), under orders for sixty days of temporary duty. Once in the theater, and with the full cooperation and assistance of Hawley and his staff, they visited the Supply Division at Cheltenham, inspected depots, and talked with US Army medical officers of the Services of Supply and the air and ground forces. Very rapidly they learned the dimensions of the medical supply crisis. "Within 10 days," Voorhees recalled, "our team unanimously reached the conclusion that only a complete reorganization, undertaken immediately, would make it possible to furnish needed hospitals and medical supplies for the invasion." Breaking off any further gathering of evidence, they returned to London to report to Hawley.42 On 7 February the Voorhees team met with the chief surgeon to discuss not only the findings but also a plan for improvement. Voorhees and his colleagues disavowed any intention to "fix fault or blame," and they acknowledged Hawley's "entire executive authority and responsibility" and his complete freedom to accept or reject their proposals. However, "to the extent that the program involves bringing key people from the US, stripping The Surgeon General's Office and Depots of top-notch personnel in this field, we would not feel justified in recommending this unless the plan as a substantial whole is found acceptable by you." The group then told Hawley: [185]

The committee laid before Hawley a three-part program, patterned, they pointed out, on the measures that had solved similar medical supply problems in the United States fifteen months earlier. First, to lighten the depots' impossible work load, they proposed that 37,000 hospital beds almost all the general and station hospital assemblies needed before D-Day - and all the required medical maintenance units for the invasion be put together in the United States, where the surgeon general's depots now had ample stocks and manpower. The ETO depots then could concentrate on equipping tactical units and on the regular receipt, storage, and issue of supplies. Second, to establish effective stock controls, Voorhees' group proposed a streamlined but more comprehensive system of reports, the development of an SOP for depot operation, reduction of the number of issuing depots, and the creation of key depots to hold reserves of scarce items. Third, the delegation addressed quantitative and qualitative manpower deficiencies, confirming Hawley's long-standing belief that here lay the source of most of his other supply difficulties. They recommended doubling the Supply Division staff, to thirty-two officers and ninety-two enlisted men, and reorganization of the division into four functional branches: Administration and Finance, Stock Control, Depot Technical Control, and Issue. Voorhees and his colleagues urged relief of Colonel Perry "without reflection upon him," and Perry's replacement with Col. Silas B. Hays, MC, who was then head of the Distribution and Requirements Division in the surgeon general's office. They presented the names of other qualified officers whom General Kirk was willing to send from the United States to the European Theater if Hawley requested them. The Voorhees group also recommended that the existing on-the-job-trained depot complements be retained and organized in permanent units, both to improve efficiency and to permit morale-enhancing promotions.44 The chief surgeon without hesitation accepted all of the group's recommendations. To implement them following still another Voorhees proposal-he assumed direct supervision of the Supply Division, superseding his Cheltenham deputy. On 10 February, in a transatlantic teletype conference, the surgeon general's office agreed to all the main points, including assembly in the United States of hospitals and maintenance units and the assignment of Hays and the other requested officers. Hangen, Beers, and Fenton moved to Cheltenham, where they effectively took over the Supply Division, with the full cooperation of Colonel Perry, who stayed on as nominal chief until Hays arrived [186]

in March. Colonel Voorhees remained in London, to work on permanent depot organization and begin a study of ways to reduce British procurement. The entire team spent February and March in sustained hard work, their efforts closely observed by General Kenner. The SHAEF chief medical officer received copies of Voorhees' reports and conferred on the supply situation with Hawley, Voorhees, and Colonel Fenton; but, as with hospital construction, he confined himself to supporting the chief surgeon's program.45 Voorhees' men rapidly reorganized the Supply Division, establishing the four new branches. By mid-March thirteen of the officers promised by the surgeon general had arrived and gone to work. The division staff expanded to thirty officers, eighty-four enlisted men, and thirteen British civilians, and for the first time in the history of the theater the reinforcements were thoroughly qualified for their jobs. After earnest and repeated pleas from Hawley, General Kirk [187]