CHAPTER IX

The Cold War, Korea, and the Cosmos

The United States emerged from World War II as the most powerful nation in the world. There would be no return to isolationism and withdrawal from world affairs as after World War I. The four-power agreements among the Allies hence forth required the continuous presence of American troops in Europe. Moreover, the Army assumed the tremendous task of administering the military governments of Germany, Austria, Japan, and Korea. Having learned from its failure to support the League of Nations, the United States spearheaded the effort to form the United Nations. Through such programs as the Marshall Plan, the United States also helped to rebuild the world that the war had shattered.

Despite its prominence in international affairs, the nation soon began to dismantle its global military communications system. To many signal officers, particularly Maj. Gen. Frank E. Stoner, wartime administrator of the Army Command and Administrative Network, the policy was shortsighted.1 Yet while the Army's ability to communicate around the world was disconnected, the technological revolution sparked by the war heralded amazing changes for the future. During the next fifteen years the Signal Corps' domain would come to include the heavens as well as the earth.

Organization, Training, and Operations, 1946-1950

With the return of peace, the Army underwent the typical postwar period of demobilization and reorganization. Discussion revolved around revamping the internal organization of the War Department and creating a unified Department of Defense. On 30 August 1945 General Marshall appointed a board of officers, headed first by Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch and later, after Patch's sudden death, by Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson, to study the first of these questions. Chief Signal Officer Ingles served as one of the members. The board, after holding extensive hearings, recommended the functional decentralization of the War Department, in particular the abolition of the Army Service Forces. With the approval of General Eisenhower, who had succeeded Marshall as chief of staff in November 1945, as well as that of President Truman, the reorganization became effective on 11 June 1946. Consequently, the Signal Corps and the other technical services returned to their prewar, independent status. Once again the chief signal officer and his counterparts reported directly to the chief of staff.2

[317]

But the scope of reorganization soon broadened to include not just the Army but the armed forces as a whole. Here the larger trend proved to be toward unification as espoused by both Marshall and Eisenhower. After much debate, Congress in 1947 passed the National Security Act, which created a unified National Military Establishment headed by a civilian secretary of defense. The new agency comprised the Departments of the Army, the Navy, and the newly independent Air Force. The secretary of war henceforth became known as the secretary of the army. Under this legislation, however, the service secretaries retained their cabinet ranks, and the defense secretary had little authority over their activities.3 This compromise approach proved unsuccessful, and in 1949 Congress amended the legislation. As a result the National Military Establishment became an executive department, the Department of Defense, with the secretary of defense acquiring a measure of control over the services. While the service secretaries lost their cabinet status, they retained authority to administer the affairs of their own departments.4

In the midst of these changes, General Ingles oversaw the Signal Corps' transition from a wartime to a peacetime basis. By 30 June 1946 the Corps' strength had dwindled to just over 56,000 officers and men, only about one-sixth of the total a year earlier.5 Due to postwar curtailment and consolidation of the Corps' activities, many of its field agencies and training facilities were discontinued, including the Central Signal Corps School at Camp Crowder.6 The Corps consolidated all of its training at Fort Monmouth, except for the small supply school at Fort Holabird, Maryland.7 In addition, the Signal Corps lost both personnel and functions to the Air Force and the Army Security Agency.

The Signal Corps suffered another severe blow with the dismantling of much of the ACAN system. General Ingles had proposed that the Army turn over the ACAN to a consortium of commercial companies to be operated as a diplomatic and governmental network during peacetime. Only during wartime, he believed, should the military resume control. Chief of Staff Eisenhower held the opinion, however, that the Army had no reason to maintain such a system at all, and in 1946 he directed the Army to divest itself of its strategic network. The Signal Corps complied, leaving stations only at major overseas headquarters. East and Southeast Asia, including Korea and Vietnam, retained no ACAN links.8 The Army's global network still included, however, the Alaska Communication System. This network acquired responsibility after the war for the portion of the Alcan telephone line running from Fairbanks to the Canadian border, and demands upon its services grew with the steady rise of population in the Alaska territory.9

The Army Pictorial Service also underwent cutbacks. V-Mail services, for example, were discontinued with the end of the war. Although Signal Corps cameramen documented war crimes trials, atomic bomb testing on Bikini atoll, and occupation activities in Germany and Japan, the Army War College photographic laboratory was closed, along with the Pictorial Service's Western Division. On the other hand, the Signal Corps resumed the sale of its photographs, suspended during the war, and requests for them multiplied.10

[318]

SIGNAL CORPS LINEMEN STRING WIRE IN POSTWAR JAPAN

Despite signs of decline, the Army's expanded worldwide commitments soon increased the demand for trained signal personnel and exceeded the capacity of Fort Monmouth's facilities to supply them. Therefore, in November 1948 the Signal Corps opened a new training center at Camp Gordon, Georgia, near the city of Augusta. Almost four decades had passed since the Corps had used this area as a winter flying school (see chapter 4). The post was named for Lt. Gen. John Brown Gordon, a Confederate officer who later served as governor of Georgia and as a United States senator. Established during World War II as a training camp, the site now became the home of the Southeastern Signal School.11

With the addition of Camp Gordon to the Signal Corps system, the Army on 23 August 1949 designated Fort Monmouth as the Signal Corps Center. In addition to the school and laboratories, the center included the Signal Corps Board, the Signal Patent Agency, the Signal Corps Publications Agency, the Signal Corps Intelligence Unit, and the Pigeon Breeding and Training Center.12

On the tactical level, divisional signal units underwent few major organizational changes in the period of upheaval following World War II. New tables of organization approved in 1948 continued to provide signal companies for infantry, airborne, and armored divisions. The 1st Cavalry Division, reorganized as infantry yet retaining its historic designation, now contained a signal company instead of a troop.13 One of the more controversial changes in the divisional tables reflected the increasing role of light aircraft. Divisional field artillery had been

[319]

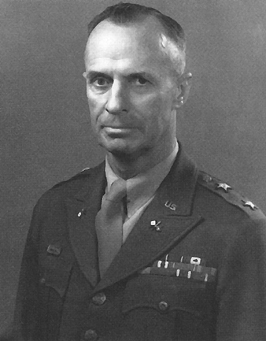

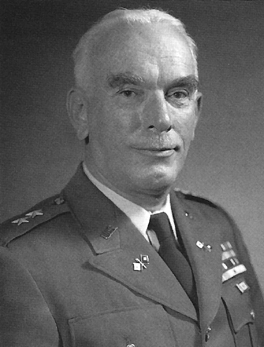

GENERAL AKIN

assigned planes since 1942; the 1948 tables assigned them to both the artillery and the division headquarters company.14 In 1952 further revisions assigned light aircraft to infantry regiments, while authorizing helicopters for the signal company and other divisional elements.15

The Signal Corps had regained its wings. During World War II the Signal Corps had used planes belonging to the Field Artillery to lay wire and deliver messages. Although the Signal Corps, as well as other branches, had lobbied to have planes allotted to it, no decision was made until the war had nearly ended. With the postwar cutbacks, aircraft did not appear in Signal Corps tables of organization and equipment for several years. Field army signal battalions were authorized liaison planes beginning in 1949, and helicopters were added in 1952.16

In June 1950 the Army Reorganization Act superseded the Defense Acts of 1916 and 1920 that provided the statutory basis for the technical services. The new law gave the secretary of the army authority to determine the number and strength of the Army's combat arms and technical services. Three branches-Infantry, Armor, and Artillery-received statutory recognition as combat arms. The Signal Corps, having thus officially lost the combat status conferred in 1920, numbered among the Army's fourteen service branches. While the technical services had survived another round in their continuing battle for existence, the act left the door open for further change by authorizing the secretary of the army to reassign the duties of any technical service, except the Corps of Engineers, along functional lines.17 At the same time, the advent of the atomic bomb seemed to have rendered conventional war and the need for large armies obsolete. By June 1950 the U.S. Army's size had contracted to less than 600,000.18

Having guided the Signal Corps through the immediate postwar period, General Ingles retired from the Army on 31 March 1947. Thanks to his wartime association with David Sarnoff of RCA, Ingles began a new career as a director of RCA and president of RCA Global Communications, Inc.19 The new chief signal officer, Maj. Gen. Spencer B. Akin, had served with distinction on General MacArthur's staff during World War II and accompanied him to Japan after the war. Within a few years his knowledge of the Far East proved particularly valuable for the branch he now headed.

[320]

Unfortunately, the tranquil peace hoped for after World War II did not materialize. New international tensions arose as the Cold War brought down an Iron Curtain between Eastern and Western Europe. The United States committed itself to the defense of Western Europe through membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), whose forces stood aligned against those of the Warsaw Pact formed between Russia and its satellites. Crises such as the Berlin blockade (1948-1949) and the victory of the Communist forces led by Mao Tsetung (Mao Zedong) in the Chinese civil war (1949) cast an ominous pall over world affairs. In that same year, Russia detonated its first atomic bomb, ending the U.S. monopoly over nuclear weapons. The arms race had begun, and the threat of nuclear war thereafter became a constant concern. Meanwhile, the foreign policy of the United States focused on the containment of communism. Although the United States had anticipated and prepared for an outbreak of overt hostilities in Europe, the first armed confrontation involving the Army came thousands of miles away, in Korea.

For forty years, since the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, Korea had suffered under Japanese rule. After World War II the United States and the Soviet Union jointly occupied Korea, with the 38th Parallel separating their jurisdictions. Although the Allies agreed to eventually grant a unified Korea full independence, the temporary boundary, as in Germany, hardened into a lasting division. To the north, the Soviets installed a Communist government, while to the south, a republic with an elected president took form. In 1948 the United States and Russia began removing their occupation troops. Completing its withdrawal in mid-1949, the United States left behind an advisory group to help train South Korea's armed forces.20 But civil unrest within the divided nation soon disrupted the fragile peace.21

On 25 June 1950 North Korean forces invaded South Korea, and the resulting conflict remains one of America's least known wars. Yet it was a bitter one. Initially, the United States did not intend to become engaged in ground combat in Korea or to fight an extended war there. The United Nations, meeting on the afternoon of 25 June, adopted a resolution calling for a cease-fire and withdrawal of the North Koreans to the 38th Parallel. However, it soon became clear that South Korea's lightly armed forces could not stop the North Koreans. The South Korean capital of Seoul fell within a few days, and the Communist forces continued to push southward. On 30 June, to prevent the nation's downfall, President Truman decided to commit American ground forces.

The United States had to draw these troops from the occupation forces in Japan, elements of the Eighth Army under the command of Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker. Four divisions were serving on occupation duty: the 1st Cavalry Division and the 7th, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions. They had lost, however, most of their World War II veterans and were not ready for combat. In addition to being seriously understrength, their World War II-vintage vehicles and equipment had

seen better days. Many critical items, such as ammunition and radios, were in short supply. Moreover, unit training opportunities had been limited by the scarcity of open space in Japan. These soldiers, accustomed to the somewhat leisurely pace of occupation duty, were about to meet a tough, disciplined, and well-equipped foe.22

The United States Army ultimately sent eight divisions to Korea (six Regular Army and two National Guard), and the Marines provided one.23 In all, twenty members of the United Nations contributed ground, air, and/or naval forces. General Douglas MacArthur, in charge of the American forces in the theater, also served as commander in chief of the United Nations Command (UNC).24

The Signal Corps faced many challenges in preparing to fight another war. By June 1950 its strength stood at only 48,500.25 To meet wartime manpower demands, Reserve signal officers and units were called up. The Signal Corps also expanded its training facilities at Forts Holabird and Monmouth and at Camp Gordon and established a new training center at San Luis Obispo, California, in December 1951.26 Moreover, the nation's sudden entrance into the war caught both the Army and industry unprepared: There had been no interim mobilization period. Unlike the two world wars, the Korean War found the Signal Corps responsible for conducting its own industrial expansion program. Shortages of various critical components arose, including polyethylene insulation and nylon covering material for wires, synthetic manganese dioxide used in high-performance dry batteries, and quartz crystals for radios. In time the Signal Corps, working with the manufacturers, found solutions to these and other production bottlenecks.27

Meanwhile the Eighth Army, which did most of the fighting in Korea, suffered from a scarcity of signal units. Its two corps-level signal battalions were unavailable, having been inactivated in Japan as part of the postwar troop reductions.28 Until the reestablishment of the I and IX Corps in the fall of 1950, the Eighth Army's headquarters signal section provided communications support directly to the subordinate divisions, placing a great strain on its limited resources.29 To meet the immediate need, three of the divisional signal companies, the 13th, 24th, and 25th, were rushed to Korea, while the 7th Infantry Division and its signal company temporarily remained behind in Japan to be "cannibalized" to provide personnel for the other divisions. Other Eighth Army signal units to see action early in the war included the 304th Signal Operation Battalion and the 522d and 532d Signal Construction Battalions.30 (Map 1)

During the first months of combat the city of Taegu became the Eighth Army's headquarters in Korea. This location had been chosen in part because it possessed good communication facilities in the form of a relay station of the Tokyo-Mukden cable.31 The Mukden cable served as Korea's main telephone-telegraph system and proved an invaluable asset during the war. In the words of Capt. Wayne A. Striley of the 71st Signal Service Battalion, "The Mukden cable advanced and withdrew with our forces. It was a great artery of communication and a godsend to the Signal Corps. I don't know what we'd have done without it "32

[322]

Initial operations went badly for the greatly outnumbered and ill-prepared American forces. The fighting began on 5 July at Osan where Task Force Smith of the 24th Infantry Division met defeat at the hands of the North Koreans. Although they put up a spirited defense, the Americans could not stop the advance of enemy tanks and infantry. To avoid encirclement, the task force made a disorderly withdrawal south to Taejon. Subsequent attempts by rein-

[323]

forcing elements of the 24th Division likewise failed to halt the North Koreans.33

Poor communications contributed to the early setbacks. Korea's mountainous terrain and its lack of good roads presented formidable obstacles to the establishment of effective command and control. The distances between headquarters were often too great for radios to net. Moreover, deteriorating batteries in the aging sets lasted only an hour or so if they worked at all, and new batteries proved nearly impossible to obtain. Wire communications proved equally tenuous. Signalmen struggled to string wire through a tortured topography of ridges, ravines, and rice paddies. Wire teams also made attractive targets for enemy ambushes, and many signalmen became casualties from such encounters. Where telephone lines could be installed, they proved difficult to maintain. Enemy artillery and tanks broke the wires, and sabotage inflicted further damage. Even fleeing refugees sometimes cut the wire, using portions as harnesses to secure their possessions. Thus, messengers frequently provided the vital links between units.34

For long-distance tactical communication, the troops depended heavily upon very high frequency (VHF), or microwave, radio. Col. Thomas A. Pitcher, who served as the Eighth Army's signal officer until September 1950, remarked that:

the VHF radio companies provided the backbone of our communications system. This method of transmission was so flexible that it could keep up with the infantry in the rapid moves that characterized the fighting in 1950-51. VHF provided communication over mountains, across rivers, and even from ship to shore. It carried teletype. It gave clear reception at all times-even when it was used at twice its rated range. After a headquarters was hooked up by wire, VHF remained as a secondary method of communication.35 |

The principal problem with VHF, which depends upon line-of-sight transmission, was the necessity of establishing stations in high and isolated locations. Since an entire station's equipment weighed two tons, with some individual pieces weighing over three hundred pounds, hand carriage of the equipment up the steep Korean slopes was extremely arduous.36 The exposed stations also made excellent targets and signal soldiers often found themselves fighting as infantry to defend their positions.37

The climate made matters even worse. Although Korea, which extends roughly from the latitude of Boston to that of Atlanta, lies within the temperate zone, it experiences extreme weather variations. During the winter Siberian winds plunged temperatures to well below zero, causing radio batteries to freeze and making it extremely difficult to lay or maintain wire.38 Radios and telephones became difficult to operate for men wearing heavy gloves. Summertime temperatures climbed as high as 100 degrees Fahrenheit, which combined with oppressive humidity to wreak havoc upon both men and equipment. The soldiers also had to contend with an annual monsoon season that generally lasted from June to September.39

[324]

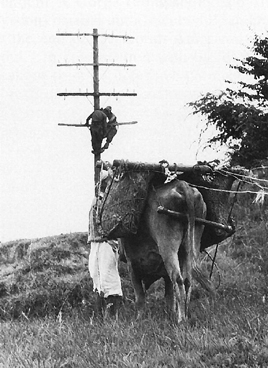

SIGNALMEN IN KOREA USE A WATER BUFFALO

TO STRETCH WIRES BETWEEN POLES

Although much of its equipment resembled that used in World War II, the Signal Corps did introduce some new devices in Korea, such as tactical radio teletype. The AN/GRC-26 mobile radioteletype station (known variously as the "Angry 26" or the "Jerk 26") became one of the Signal Corps' most useful pieces of equipment and proved rugged enough to withstand travel over the rough Korean roads.40 The Corps also employed improved ground radar to locate enemy mortar emplacements. These sets had been engineered on a crash basis with the Sperry Gyroscope Company, and they began to arrive in the field late in 1952.41 The Corps also benefited from lighter field wire with better audio characteristics than its World War II counterpart.42

Above the battlefield, the Signal Corps put its restored wings to work. The aviation section of the 304th Signal Operation Battalion, for example, used five L-5 "mosquito" planes to carry as much as 34,000 pounds of messages a month between the Eighth Army and its corps headquarters. Aerial delivery worked especially well for maps, charts, and other bulky documents that could not be transmitted readily by radio or wire. Planes could do the job in a few hours when delivery by jeep might take several days.43 The Signal Corps also employed planes to lay wire in areas where the terrain proved too rough for signalmen to do it on the ground.44 In addition, the Signal Corps used wings of another variety, those belonging to its carrier pigeons, which flew many important messages over the fighting front.45

As in the past, signal units provided photographic coverage of the war for tactical, historical, and publicity purposes. Instead of separate photo companies, as in World War II, signal battalions at army and corps level were responsible for combat photography. In addition, divisional signal companies now included photo sections. Each section contained seven still photographers and two motion picture cameramen who performed ground as well as aerial photography. The section's six laboratory technicians could process still photos in the field, despite the difficulties of temperature control and limited supplies of fresh water. When necessary, cellular photographic units could also be called upon for special missions.46

[325]

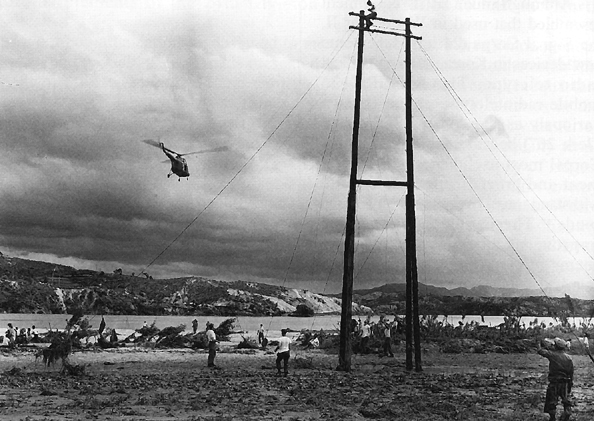

SECURING FIELD WIRE DROPPED FROM A HELICOPTER NEAR THE NAKTONG RIVER

The enemy, meanwhile, generally employed less sophisticated signaling techniques. The North Korean Army used radios and other communications equipment supplied by the Soviet Union.47 When China entered the war in November 1950, its forces operated without radios, communicating with whistles, bugles, and horns. Often these same devices also served as weapons of psychological warfare. During the night, for example, UN soldiers sometimes heard the eerie sound of an enemy bugler playing taps. Although these methods were primitive, they proved surprisingly effective.48

During August and September 1950 the Eighth Army successfully defended the "Pusan Perimeter"-actually a rectangle about 100 miles long and 50 miles wide bounded by the Naktong River on the west and the Sea of Japan on the east. The city of Pusan, the best port in Korea, sat on its southeastern edge.49 Taegu lay dangerously close to the threatened western edge, and North Korean advances toward the city early in September forced the evacuation of the Eighth Army's headquarters to Pusan. General Walker ordered the move largely to protect the army's signal equipment, especially its large teletype unit, the only one of its kind in the country. Despite a determined North Korean effort to break through the defenses and drive the Americans into the sea, the Eighth Army held on.50

[326]

On 15 September 1950 the independent X Corps (comprising the 7th Infantry Division and the 1st Marine Division) carried out a successful landing behind enemy lines at Inch'on, and by the end of the month American and South Korean forces had recaptured Seoul.51 In coordination with the Inch'on landing, the Eighth Army initiated a breakout from its defensive perimeter on 16 September. As North Korean resistance deteriorated in the wake of the reverses at Inch'on and Seoul, the Eighth Army rapidly swept northward to link up with the X Corps. Disorganized, defeated, and demoralized, the North Koreans retreated behind their borders. Victory appeared to be at hand as UN forces crossed the 38th Parallel into North Korea early in October, entering the capital of P'yongyang on the 19th. In order to completely destroy the North Korean armed forces and reunify Korea, UN troops continued to advance toward the Yalu River on the Manchurian border. MacArthur announced that the war would be over by Christmas, but his optimism proved tragically premature.

The war suddenly took on a new dimension when China intervened, as it had threatened to do if UN forces invaded North Korea. South Korean troops heading for the Yalu first encountered Chinese soldiers on 25 October.52 Battle hardened veterans of the recent civil war, the Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) soon attacked the UN units in large numbers. Despite the lack of air support and tanks, and with very little artillery, the Chinese defeated the Eighth Army in western Korea and the X Corps at the Chosin Reservoir in late November. They then pursued MacArthur's forces back across the 38th Parallel and by early January had regained control of Seoul. Instead of celebrating the holidays and victory at home, the UN troops fought on throughout the harsh Korean winter.

Throughout these tumultuous months the 7th Signal Company performed exemplary service. It received the first of four Meritorious Unit Commendations it earned in Korea for its support of the 7th Infantry Division from September 1950 to March 1951. The company provided communications during the landing at Inch'on and accompanied the division to the Yalu. At Chosin the signalmen fought alongside the infantry, often dismounting radio equipment so their trucks could be used as ambulances. Throughout the withdrawal, the company maintained a complete communications network until all friendly troops had departed, and then safely evacuated over 400 tons of signal equipment.53

After the retreat from North Korea, the X Corps consolidated with the Eighth Army under the leadership of Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, who assumed command in December 1950 after General Walker's death in a traffic accident.54 The new commander intended to resume offensive operations as soon as possible. In his planning, Ridgway emphasized communications, stating that he "wanted no more units reported ‘out of communication’ for any extended period."55 When telephones and radios failed, he urged the use of runners and even smoke signals if necessary. By the end of March 1951 the Eighth Army under Ridgway had retaken Seoul and largely cleared South Korea of Chinese and North Korean troops.56

[327]

A MEMBER OF THE 40TH SIGNAL COMPANY WASHES

NEGATIVES IN AN ICY KOREAN MOUNTAIN STREAM

Shortly afterward, General Akin's retirement brought a change of leadership to the Signal Corps. On 1 May 1951, Maj. Gen. George I. Back, a veteran of both World Wars I and II, became the new chief signal officer. From September 1944 to November 1945 he had been chief signal officer of the Mediterranean theater. Having served as signal officer of the Far East Command since 1947 and as signal officer, UNC, since 1950, General Back brought to the job an extensive background of knowledge about Korea. He called upon this experience to guide the Signal Corps through the remainder of the war.57

Despite Eighth Army's recent successes, the conflict became increasingly unpopular at home. MacArthur supplied additional controversy with his criticism of Truman's war policy, which led to MacArthur's relief as the theater commander and replacement by Ridgway.58 Direct Soviet involvement remained a dire possibility that could lead to World War III, but fortunately did not occur. With neither side able to secure a decisive military advantage, truce negotiations began in July 1951 and continued for two years. In the interim, fighting persisted on a limited scale. Many lives were lost in such bitter engagements as Heartbreak Ridge and Pork Chop Hill, but the battle lines remained virtually unchanged.

In the end, diplomacy halted the Korean War, with victory for neither side. Early in 1953 newly elected President Dwight D. Eisenhower traveled to the battlefront to fulfill a campaign pledge. Following his visit and a veiled threat to use atomic weapons, the belligerents finally signed an armistice agreement on 27 July 1953 at the village of Panmunjom. According to its terms, Korea remained divided by a demilitarized zone roughly following the 38th Parallel.

What has been called the "forgotten war" cost the United States Army nearly 110,000 casualties, 334 of them belonging to the Signal Corps.59 Throughout

[328]

GENERAL BACK

the fighting, signal soldiers won recognition both as individuals and as units. While none received the Medal of Honor, two members of the 205th Signal Repair Company, Capt. Walt W. Bundy and 2d Lt. George E. Mannan, were posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for heroic action at Wonju during the night of 1-2 October 1950 when they covered the escape of seventeen enlisted men from their overrun position at the cost of their own lives.60 A notable honor was won by the 272d Signal Construction Company, one of several black signal units that served in Korea. The 272d participated in six campaigns and earned the Meritorious Unit Commendation for operations during 1950 and 1951.61

After preserving the independence of South Korea, the Eighth Army remained to enforce the peace. Its signal units continue to provide the U.S. forces stationed in that country with a sophisticated communications system.

Based upon wartime efforts, the post World War II era witnessed revolutionary advances in science and technology. The Signal Corps, having already proven that it could send messages anywhere in the world, now looked to the heavens for new frontiers in communications.

The first breakthrough came on 10 January 1946 when scientists at the Evans Signal Laboratory succeeded in bouncing a radar signal off the moon. This project, named Diana for the Roman goddess of the moon, proved that humans could communicate electronically through the ionosphere into outer space. To accomplish this feat, the Signal Corps adapted a standard SCR-271 radar to transmit the signal. At almost 240,000 miles, this was certainly a long-distance communication; a new space-age era in signaling had begun.62

In spite of this promising start, postwar austerity stunted the initial growth of the space program. To many, including the prominent scientist Vannevar Bush, satellites and space travel still belonged to the realm of science fiction. The Korean War, however, brought increased defense spending, and space-related research benefited.63

[329]

The Army hoped to put the United States' first satellite into orbit during the International Geophysical Year (IGY) to be held from July 1957 to December 1958. The IGY was the latest in the series of international scientific undertakings, in which the Signal Corps had participated, that had begun with the International Polar Years of the 1880s and the 1930s. The interval between events had now been reduced from fifty to twenty-five years, largely due to the accelerated pace of technological progress during and after World War II. The new name reflected the wider scope of activities. In 1954 the Special Committee for the International Geophysical Year, meeting in Rome, recommended that the launching of earth satellites be a major goal of the IGY's research effort. The Army's plan, known as Project Orbiter, had to compete with proposals made by the Navy and the Air Force. Ultimately, a special Department of Defense advisory committee selected the Navy's Vanguard program. The Signal Corps, however, operated the primary tracking and observation stations, one in the United States and five in South America.64

But the Soviet Union took command of the heavens first. Its successful launching of Sputnik on 4 October 1957 shocked the nation. Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas, who soon began an inquiry into satellite and missile programs, called the event a "technological Pearl Harbor."65 If the Russians could send satellites into space, some argued, then they probably could launch long-range missiles capable of destroying the United States. Many Americans reacted strongly to this perceived threat and wanted to match the Soviets as quickly as possible. As the "space race" began in earnest, the Cold War acquired cosmic complications.

The Soviet achievement did not occur as abruptly as it might have seemed, for the Russians had devoted considerable resources to rocketry since the 1930s.66 The success of the German V-1 and V-2 ballistic missiles during World War II spurred both the United States and the Soviet Union to undertake similar programs. (Although with less spectacular results than the Germans, American scientist Robert H. Goddard had conducted important experiments with liquid-fuel rockets during the 1920s and 1930s. During World War I his early research had received financing from the Signal Corps.)67 The surrender of leading German rocket scientists, in particular Wernher von Braun, to the U.S. Army in 1945 brought invaluable expertise to this country via "Project Paperclip." The Russians, meanwhile, captured many of the German laboratory facilities. While the United States' missile program lagged after the war, the Soviet Union's forged ahead.68

The Russians quickly followed up their initial triumph with the launching of Sputnik II in November 1957. This time a canine passenger went along for the ride. Having suffered a second psychological blow, the United States moved quickly to close the technological gap and recover its lost national prestige. On 31 January 1958 the United States launched its first satellite, Explorer I. The Army could take credit for this accomplishment through the work of von Braun and his team of rocket experts at Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, working in conjunction with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of the California Institute of Technology. Had

[330]

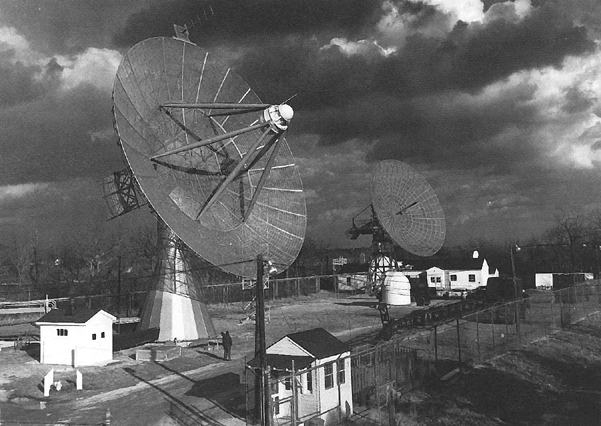

THE SCR-271 RADAR SET USED TO BOUNCE SIGNALS

OFF THE MOON DURING PROJECT DIANA

the Army's plan originally been accepted for the IGY, the United States very likely could have been the first into space. In addition to salvaging the nation's pride, Explorer, loaded with sophisticated electronic equipment-components of which had been developed by the Signal Corps-contributed greatly to the scientific knowledge obtained during the IGY by discovering the Van Allen radiation belt encircling the earth.69

After many frustrating delays and the spectacular failure of its first launch attempt (which earned the project the nickname "Flopnik"), the Navy successfully launched Vanguard I on 17 March 1958. As part of its payload the satellite carried solar cells developed by the Signal Corps that helped to meet the sustained power requirements of space travel. Vanguard II followed in February 1959, carrying an electronics package created by the Signal Corps. The payload included infrared scanning devices to map the earth's cloud cover and a tape recorder to store the information. Unfortunately, technical problems with the satellite's rotation limited the usefulness of the images obtained.70

Military dominance of the space program proved to be short-lived. In July 1958 President Eisenhower signed into law an act establishing the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The new agency, which came into being on 1 October 1958, absorbed the existing National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which dated from World War I. To provide future scientists, the government subsidized an expanded science curriculum in the public schools to train the technicians needed to win the space race.71

Yet military participation in the field continued. On 18 December 1958 the Signal Corps, with the help of the Air Force, launched the world's first communications satellite. Designated Project SCORE (Signal Communications via Orbiting Relay Equipment), this venture demonstrated that voice and coded signals could be received, stored, and relayed by an orbiting satellite. Its system

[331]

THE SIGNAL CORPS ENGINEERING LABORATORY'S ASTROPHYSICS OBSERVATORY AT CAMP EVANS,

NEW JERSEY, 1959. THE PARABOLIC ANTENNAS TRACKED THE EARLIEST U.S. AND SOVIET SATELLITES.

could carry one voice channel or seven teletype channels at sixty words per minute. Among its notable feats, SCORE broadcast tape-recorded Christmas greetings from President Eisenhower to the peoples of the world. This pioneering signal station, unfortunately, had a life expectancy of only a few weeks.72

The Signal Corps also became involved with the Courier program, a joint military-industrial endeavor to create the first satellite using ultra-high frequency (UHF) communications. This portion of the electromagnetic spectrum had remained relatively unused and generally free from man-made and atmospheric interference. The Courier satellite could simultaneously transmit and receive approximately 68,000 words per minute while moving through space at 16,000 miles per hour, and could send and receive facsimile photographs. Courier went aloft in October 1960 but inexplicably stopped communicating after seventeen days. Nevertheless, it represented another step forward in space-age signals.73

Despite such achievements and the Army's early lead in space technology, its role in the space race became a supporting one. The creation of NASA had institutionalized civilian control of the space program and emphasized America's peaceful purposes. As for the development of the military uses of outer space, the Department of Defense assigned this responsibility to the Air Force in September

[332]

1959.74 Although the Army and the Signal Corps continued to make important contributions to the overall effort, the formation of the Army's Satellite Communications Agency in 1962 ended the Signal Corps' direct role in developing satellite payloads.75

During this period the Signal Corps also cooperated with the Weather Bureau, RCA, and several other organizations in developing the world's first weather satellite, TIROS (Television and Infra-Red Observation Satellite), launched by NASA in April 1960. Meteorology now soared to heights undreamed of by Myer, Hazen, Greely, or Squier. From its orbit about 450 miles above the earth, TIROS used two television cameras to photograph the clouds. Ground stations at Fort Monmouth and in Hawaii instantaneously received the photographic data. A second TIROS satellite, launched in November 1960, provided additional atmospheric data, and eight more followed over the next five years.76

Other satellites ushered in a communications revolution, connecting the world in a way wire and cables never could. In July 1962 NASA and AT&T jointly launched Telstar, the first active communications satellite, which picked up, amplified, and rebroadcast signals from one point on the earth to another. (A passive satellite only reflects the signals received.)77 Weighing just thirty-five pounds and only three feet in diameter, Telstar broadcast the first live television pictures between continents and illustrated the tremendous potential of space-age signals. Later that year Congress passed the Communications Satellite Act of 1962 setting up the quasi-governmental Communications Satellite Corporation (COMSAT). It, in turn, managed an international consortium (INTELSAT), whose member nations shared access to the global telecommunications satellite system. Among their benefits, INTELSAT satellites increased the number of transoceanic telephone circuits and made real-time television coverage possible anywhere in the world.78 Meanwhile the military, in conjunction with NASA, launched a series of communications satellites, known as SYNCOM, into synchronous orbit with the earth. Because these satellites remained at a fixed point in relation to the earth, they did not require tracking stations.79

Soviet propaganda and American panic to the contrary, Sputnik had not placed the Soviet Union light years ahead of the United States in the space race. Since 1957 Americans had attempted and accomplished more difficult missions than the Russians and in fact held the lead in satellite technology both for scientific and military purposes. Thanks in part to the work of the Signal Corps, beginning with Diana's echoes just twenty-three years earlier, the United States capped its achievements in space in 1969 by landing the first men on the moon.80

From Signals to Communications-Electronics

By the end of 1953 the Signal Corps' strength had grown to approximately seventy-five hundred officers and eighty-three thousand enlisted men as a result

[333]

of the Korean War. But these numbers soon began to dwindle as the inevitable postwar reductions took effect. With the drawdown the Corps closed its schools at Fort Holabird and Camp San Luis Obispo.81 The Korean War stimulated, however, a long-term expansion of the Signal Corps' research and development program, whose budget nearly doubled between 1955 and 1959.82 The introduction of increasingly sophisticated electronic devices seemed to change the nature of communications almost overnight. Moreover, the proliferation of these devices throughout the Army engaged the Signal Corps in several new areas of operation.

For years the Corps had carried out its scientific experimentation in the three laboratories at or near Fort Monmouth: Coles, Evans, and Squier, known collectively as the Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories. To centralize their operations, they began moving into a new, specially designed building at Fort Monmouth in 1954, known as the Hexagon.83 In 1958 the Army redesignated this facility as the U.S. Army Signal Research and Development Laboratory.84 There the Corps pursued a long-range program that emphasized advances in the areas of miniaturization and systems integration.

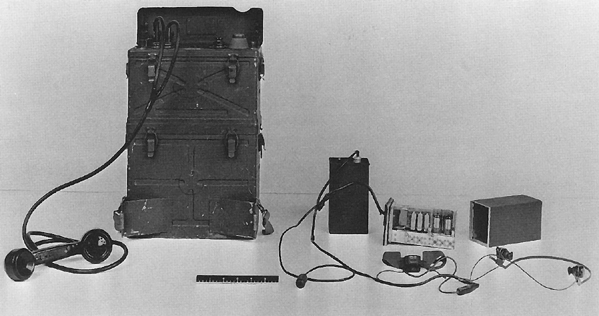

The trend toward miniaturization had begun prior to World War II with the walkie-talkie. The latest version of the device, introduced early in the 1950s, was only about one-half the size and weight of the World War II model and represent ed the upper limit of miniaturization possible with vacuum tube technology. The redesigned handie-talkie, meanwhile, operated on FM, finally making it compatible with the walkie-talkie. At the same time, the Signal Corps introduced a new series of FM vehicular radios whose components could be arranged in different combinations and easily replaced. The radios also worked in conjunction with the walkie-talkie and the handie-talkie. A new, portable teletypewriter weighed just forty-five pounds, only one-fifth as much as the older equipment, and could be carried by a paratrooper on a drop. Not only did it transmit and receive messages more than twice as fast as previous models, it also was waterproof and therefore suitable for amphibious operations. Field switchboards weighing just twenty-two pounds also began coming off the production lines. Field telephones likewise underwent a weight reduction program, losing some three pounds and slimming down by one-third in size. Several of these streamlined items had begun to appear on Korean battlefields before the war ended.85

The key to further improvement was the development of the transistor. The Signal Corps, in conjunction with the electronics industry, in particular Bell Laboratories, facilitated the creation of this revolutionary device that helped to change the shape of communications after World War II. During the 1950s the Signal Corps subsidized much of the research and production costs and became, in fact, the military's center of expertise in this field.86 The transistor held many implications for military communications: Its small size and low power requirements meshed perfectly with the trend toward miniaturized equipment. A transistor, made of a solid material such as silicon that acts as an electrical semiconductor, operated much more quickly than a vacuum tube and proved less susceptible to damage and such environmental factors as heat, cold, moisture, and fun-

[334]

THE HEXAGON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CENTER AT FORT MONMOUTH, NEW JERSEY

gus.87 Composed of several layers of material, it can be thought of as an electronic sandwich. Rugged, reliable, and portable, the transistor met the demands of battlefield communications.

The subsequent invention in 1958 of the integrated circuit, or electronic microchip, helped usher in the Information Age. Messages to be communicated became information to be processed. An integrated circuit contains all the components that form a complete circuit, to include transistors arrayed on a tiny silicon slice. The necessary interconnections, or wires, are printed onto the chip during manufacture. This type of circuitry is known as solid-state because it has no moving parts, hence its enhanced durability. A single microchip can handle many times the communications load of a traditionally wired circuit while taking up much less space. This innovation, which allowed increasingly powerful yet smaller machines to be built, eventually led to the ubiquitous desktop personal computers of the 1980s and 1990s.88

Like Myer's original wigwag code, most computers operate according to a two-element or binary system. Instead of the left and right movements of a signal flag, a computer reads electrical signals in the form of the digits 1 and 0. Digital signals are not continuous like radio waves but rather a series of discrete on and off impulses like those of a telegraph. According to a computer's binary code, the digit 1 represents on and 0 represents off. In early computers, mechanical switches opened and closed to control the current. Later, vacuum tubes and then transistors provided electronic gateways. Through this simple process of on and off signals the complex circuitry of a computer performs complicated tasks very rapidly.89

[335]

THE RESULTS OF THE ARMY'S MINIATURIZATION PROGRAM ARE EVIDENT IN THIS COMPARISON OF THE

SCR-300 AND AN/PRC-6 RADIOS

Electromechanical computers had been built prior to World War II. Vannevar Bush and associates at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology had constructed the differential analyzer in the 1920s to solve complex mathematical equations related to electrical engineering. During the war the Army used this machine to compute artillery-firing tables.90 The Signal Corps, meanwhile, used IBM punch card machines to analyze large amounts of data, a technique that proved especially useful in code and cipher work. In Britain a computer called Colossus helped crack the Enigma code.91 Between 1943 and 1946 two scientists at the University of Pennsylvania, John W. Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, Jr., developed an electronic digital computer for the Army to speed up the calculation of firing tables. Known as ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), it employed 18,000 vacuum tubes and weighed nearly thirty tons. Other early computers were similarly mammoth machines.92

During the 1950s the Signal Corps studied the feasibility of using computers for tactical application, and subsequently undertook the development of a farsighted program known as Fieldata that envisioned the coupling of computers and communications systems into worldwide networks. In December 1959 Sylvania delivered to the Signal Corps for testing the first model of a family of machines with the designation MOBIDIC (with some humor intended, no doubt, alluding to its large size). The acronym actually stood for mobile digital computer. These transistorized machines, designed to fit into a thirty-foot trailer van, would process information on such battlefield conditions as intelligence, logistics, firepower, and troop strength. Philco and IBM received contracts to build smaller computers, known as Basicpac and Informer. Although

[336]

Fieldata anticipated such developments as compatible computers and standard codes, budget constraints led to the premature termination of the program during the 1960s. By the 1980s technological advances finally made such an integrated system possible.93

The advent of the electronics age brought about the demise of one of the Signal Corps' oldest forms of communications, pigeons. The Army's birds, like horses and mules before them, had fallen victim to progress. Consequently, the Signal Corps closed the Pigeon Breeding and Training Branch (formerly Center) at Fort Monmouth on 1 May 1957. The Corps sold its birds to the public except for the remaining war heroes, such as G.I. Joe, which it presented to zoos around the country. Although the U.S. Army considered them obsolete, some nations, such as France, retained their feathered messengers for use in the event that more modern forms of communication failed.94

Progress brought other changes to Fort Monmouth where, until the early 1950s, the Signal Corps conducted the extensive experimentation associated with electronic warfare. The urban location of the post became a liability, however, due to interference from neighboring radio and TV stations, airports, and other sources ranging from power generators to electric toothbrushes. Consequently, in 1954 the Army established the Electronic Proving Ground at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, an isolated spot in mountainous, desert country about seventy miles south of Tucson. There the Signal Corps could test the latest equipment on thousands of acres relatively free from human or electronic interference. The fort also held historical significance for the Signal Corps, having been the site of a heliograph station during the Geronimo campaign in 1886 and again during the 1890 departmental tests. Now it would host investigations into such areas as battlefield surveillance, avionics, and meteorology.95

In 1957 the Signal Corps established the U.S. Army Combat Surveillance Agency to carry out its missions of combat surveillance and target acquisition. The agency also coordinated the Signal Corps' efforts with those of the other armed services, government agencies, and industry. The Signal Corps' work in this field included the development of such devices as drone aircraft, ground and airborne radar, and infrared sensors.96

Under the 1947 defense act the Army acquired responsibility for tactical missiles while the Air Force controlled strategic weapons. The Army conducted its guided missile research at the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico. Von Braun and his team of experts had initially worked there before moving to Redstone Arsenal. The Signal Corps, meanwhile, established a field agency at White Sands to provide missile range instrumentation.97 Among its important contributions to air defense, the Corps worked with private industry to develop the Missile Master, an electronic fire control system for Nike air defense missiles.98

The Army's increased use of aviation called for a type of expanded communications support which became known as avionics. In addition to radio communication, this term included electronic aids to navigation, instrumentation, stabilization, and aircraft identification and recognition. Lightweight electronic equip-

[337]

ment developed by the Signal Corps met the stringent weight requirements of the Army's relatively small aircraft.99 To control Army air traffic in the battle zone, the Signal Corps developed a mobile flight operations center mounted in vans and trailers.100 In 1954 the Signal Corps became responsible for the Army Flight Information Program to furnish Army aviators with current flight data such as charts, maps, and technical assistance.101

On and off again like the weather itself, the Signal Corps' meteorological activities resurged in the post Korean War period, in part to support the expanded Army aviation program. Although the Air Force provided operational weather support for the Army, the Signal Corps supplied the associated communications. As it had since 1937, when it lost control of most of its weather-related activities, the Signal Corps remained the primary agent for Army meteorological research and development.102 The Corps conducted much of this work in the Meteorological Division of the laboratories at Fort Monmouth, with some aspects assigned to the proving ground at Fort Huachuca. Since weather affects even the most sophisticated communications-causing distortion or disruption-the Signal Corps needed to learn more about such phenomena, and the curriculum at Fort Monmouth included courses in meteorological observation. In 1957 the U.S. Army Signal Corps Meteorological Company, the only unit of its kind, was formed at Fort Huachuca. Its nine teams were scattered around the globe to supply meteorological support for special testing exercises.103 The Signal Corps even explored ways to control the weather, joining with the Navy and General Electric in cloud-seeding experiments.104 Besides weather prediction, information about winds and conditions in the upper atmosphere proved crucial to missile guidance and control. The influence of weather upon radioactive fallout also warranted serious study.

Modern technology provided weather watchers with many new tools. In addition to the weather satellites already discussed, the Signal Corps pioneered many other techniques. In 1948 Signal Corps scientists at Fort Monmouth used radar to detect storms nearly 200 miles away and track their progress. New high-altitude balloons carried radiosondes (miniature radio transmitters) more than twenty miles aloft to transmit measurements of humidity, temperature, and pressure. To conduct atmospheric studies beyond that range, the Signal Corps used rockets. The Corps developed an electronic computer that could determine high-altitude weather conditions faster and more accurately than any other type of equipment. Using the wealth of data available, computers could also perform the many calculations needed to produce a forecast.105

In connection with the IGY, Signal Corps scientists conducted climatological studies around the world. Amory H. Waite, who had traveled extensively introducing new equipment during World War II, directed Signal Corps research teams in Antarctica, an area about which little was then known. In addition to making meteorological observations, these men gathered electromagnetic propagation data through the ice and tested various types of equipment. The Signal Corps conducted similar studies at the North Pole and made weather observations

[338]

with rockets at Fort Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. The Corps also explored the upper atmosphere to learn more about its effects on communications.106

While satellites orbited above, the changing nature of communications had a significant impact at ground level as well. The Army needed satellite and missile tracking stations around the globe, making modernization of the ACAN imperative. To meet its short-term needs, the Signal Corps could call upon the commercial communication companies for assistance. For the long-term, the Corps began planning an entirely new system-UNICOM, the Universal Integrated Communications System. With computers making rapid automatic switching possible, UNICOM would provide greater speed and security in a variety of modes: voice, teletype, digital, facsimile, and video. Implementation of the system began in 1959, with completion slated for as late as 1970, depending upon available resources.107

Meanwhile, the immediate future of one portion of the ACAN remained in doubt as the Signal Corps once again contemplated the disposition of the Alaska Communication System. In 1955 the Signal Corps drafted legislation to authorize its sale but with no results.108 In June 1957, however, the ACS underwent a significant change in mission: It was separated from the ACAN and relieved of primary responsibility for providing strategic military communication facilities at Seattle and within Alaska. Henceforth the system became essentially a public utility, while continuing to serve military and other government agencies in Alaska. Subsequent improvements to the system included the installation of a new cable in 1955 between Ketchikan and Skagway by the Army's cable ship, Albert J. Myer. This cable, in conjunction with one laid by AT&T from Ketchikan to Port Angeles, Washington, more than doubled the existing capacity of radio and landline telephone circuits between Alaska and the United States.109

While the service provided by the ACS had been significantly improved, disaster loomed ahead. Earthquakes in 1957 and 1958 damaged equipment and disrupted communications, but they merely served as preludes to the major earth quake of March 1964, which devastated the region. As in San Francisco nearly sixty years earlier, Army units stationed in the area contributed greatly to the relief effort. The 33d Signal Battalion, with headquarters at Fort Richardson, provided vital communications to civilian agencies and communities during the emergency.110 Although Alaska entered the Union in 1959 as the forty-ninth state, the Army continued to operate the ACS until 1962. At that time it finally divested itself of the system it had maintained since 1900 by transferring it to the Air Force. In 1971 the Air Force sold the ACS to RCA, bringing nearly a century of military communications in Alaska to an end.111

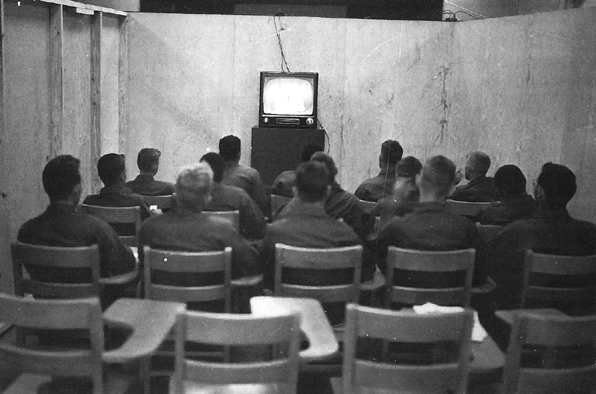

The post-Korea era also witnessed the invasion of a new and powerful communications medium into American homes. The economic restrictions imposed by World War II and Korea and the consequent diversion of raw materials to war production had delayed television's widespread commercial introduction. With peacetime, television boomed. Glowing cathode-ray tubes increasingly became a fixture in America's living rooms, and mass communication took on a new face.

[339]

CAMERAS AND TRANSMITTING VAN OF THE SIGNAL CORPS MOBILE TELEVISION SECTION; BELOW

STUDENTS RECEIVE TELEVISION INSTRUCTION

[340]

The Army, too, began to explore the applications of this electronic messenger. For combat purposes, the Signal Corps built a mobile television unit employing both ground-based and airborne cameras. Tested during maneuvers, this system promised to allow a commander to observe the battlefield and to control his units personally and more effectively. In August 1954 the Army held the first public demonstration of tactical television at Fort Meade, Maryland.112

Television also held much promise for training and educational purposes. During the 1950s the Signal Corps introduced its use at Forts Monmouth and Gordon. Tests demonstrated that television adapted particularly well to the teaching of motor skills-such as the assembly of electronic components. For some subjects it even proved superior to conventional teaching methods. By means of television, one instructor could teach a large number of students, while retaining the sense of individual instruction. The use of film and later videotape eliminated the need for the instructor even to be actually present in the classroom. Television also reduced training time and saved money. Having proven television's utility, the Signal Corps soon began assisting other branches with the development of televised training programs.113

In 1951 the Signal Corps began production at its Astoria studios of a public service television program, "The Big Picture." Initially focusing on the war in Korea, this award-winning documentary series used Signal Corps footage to bring news of the Army's activities into millions of homes each week. Its scope later expanded to include all aspects of the Army's role and mission around the world. By 1957 more than 350 stations carried the program. "The Big Picture" remained on the air for nearly twenty years, until the Army ceased production in 1970.114

Along with its achievements in space during the 1950s and early 1960s, the Signal Corps pioneered in the field of electronics and its military applications. The Corps' role in the development of the transistor and the use of computers for information processing produced fundamental changes in the nature of communications technology, the effects of which are still being felt.

Force Reductions, Readiness, and the Red Scare

As the space race had made manifest, the communications revolution of the 1950s took place in a political atmosphere of suspicion and hostility between the United States and the Soviet Union. The persistent Soviet threat required the maintenance of a strong defensive posture, despite the pressures to cut the military budget in the aftermath of the Korean War. President Eisenhower's defense policy, known as the New Look, placed reliance on nuclear deterrence rather than on the strength of the ground forces. Consequently, the Army experienced substantial manpower cuts during the 1950s. Meanwhile the United States, closely followed by the Soviet Union, developed tactical nuclear weapons. By 1956 both nations also possessed hydrogen (thermonuclear) bombs a thousand times more powerful than those dropped on Japan.115

[341]

To meet the contingency of either nuclear or conventional war while keeping within its reduced budget, the Army reorganized its World War II triangular divisions. The new formations, known as pentomic divisions, consisted of five battle groups that could operate independently or concentrate for a major attack. The Regular Army finished reorganizing its divisions by the end of 1957, while the Army Reserve and National Guard completed their divisional restructuring in 1959. These leaner divisions were intended to meet the demands for personnel reductions while providing the capability to engage in modern warfare on a dispersed and fragmented atomic battlefield. Under such conditions, however, communications gained greater importance for command and control. Hence, divisional signal companies were expanded into battalions.116

To achieve operational flexibility, the Signal Corps devised the area communications system, a multiaxis, multichannel network. The system sought to satisfy the requirements of atomic warfare: mobility, invulnerability to attack, increased capacity, faster service, and greater range. Unlike the single axis system of the past, a multichannel network could withstand a breakdown in one area, such as that caused by a nuclear attack, and reroute communications along an alternate path. Such built-in redundancy had not been available in Korea, and its absence resulted in frequent communication shutdowns. Radio relay and multichannel cable formed the backbone of the system, with messengers, wire, and radioteletype also available.117 Later advances in electronics technology helped to make the system work as the Signal Corps adopted transistorized equipment that operated automatically without the inherent delay caused by operators. By 1958, for example, the Signal Corps possessed a family of teletypewriters that handled messages at a rate of 750 words per minute. Smaller and lighter radios, meanwhile, covered a greater range of frequencies than their predecessors.118

Modern weaponry and equipment enabled the Army to fight more effectively despite its shrinking size. Active strength dropped below 900,000 in 1958.119 At the same time, greater reliance on high technology increased the demand for skilled communications-electronics specialists. The Signal Corps revised its training curriculum accordingly, adding such courses as atomic weapons electronics, electronic warfare equipment repair, and automatic data processing. During the four years from 1955 to 1959 the Signal Corps trained 9,000 officers and 99,000 enlisted men at its schools.120 Yet a shortage of skilled communicators became a chronic problem as the Signal Corps competed for personnel with the higher-paying civilian electronics industry.

Along with rising international tensions, the Cold War intensified domestic paranoia, and the Signal Corps became caught up in the host of Communist spy investigations and trials that pervaded the period. During the late 1940s Congressman Richard M. Nixon of California gained national prominence as a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), particularly for his role in the case of Alger Hiss, a State Department official who had spied for the Russians. With Hiss and others as evidence of widespread subversion, fear

[342]

GENERAL LAWTON GREETS SECRETARY OF THE ARMY STEVENS. SENATOR MCCARTHY IS ON

GENERAL LAWTON'S RIGHT. CHIEF SIGNAL OFFICER BACK IS SECOND FROM LEFT.

of communism became a national obsession. The trial and conviction of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in 1951 for passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union, played out against the backdrop of the Korean War, heightened the nation's fears. Even the couple's execution in 1953 did little to reassure the American public that the Communist menace was not omnipresent.

During the early 1950s Senator Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin attained notoriety for his investigations into alleged Communist infiltration into American government, particularly the State Department. Loyalty and conformity became paramount, and the word "McCarthyism" entered the American lexicon. Eventually the senator's attention turned to the armed forces and to the Signal Corps in particular. During World War II Julius Rosenberg had worked for the Signal Corps as an electrical engineer, though he had lost his job in 1945 due to charges that he belonged to the Communist Party.121

The Signal Corps had scrutinized its security procedures in 1952 after a defecting East German scientist reported that he had seen microfilmed copies of documents from Fort Monmouth. The resulting investigation uncovered neither missing documents nor evidence of espionage. In addition, both the FBI and the HUAC conducted probes at Fort Monmouth to no avail. In late 1953, however, McCarthy picked up the scent, and even cut short his honeymoon in the West Indies to rush to Washington to begin hearings into subversion within the Signal

[343]

GENERAL NELSON |

Corps. The source of the latest accusations was Maj. Gen. Kirke B. Lawton, commander of Fort Monmouth, who had secretly warned the senator of possible subversion at the post. McCarthy used his committee's hearings to fan fears that a spy ring started by Rosenberg continued in operation at the Evans Signal Laboratory. During the probe the Army suspended many civilians from their jobs, but no indictments ever resulted.122 McCarthy tried again to implicate the Signal Corps the following year when he accused a civilian employee, Mrs. Annie Lee Moss, of being a member of the Communist Party and having access to top secret messages as an Army code clerk. These allegations were also never proven.123

The most immediate result of these investigations into the Signal Corps was their effect on McCarthy himself, for they contributed greatly to his political downfall. Televised proceedings of his subcommittee, known as the Army McCarthy hearings, began in April 1954 and created a national sensation. The senator's virulent attacks on the Army helped to turn public opinion against him. In December 1954 the Senate condemned McCarthy, who thereafter retreated from the public spotlight and died in 1957.124

During this period of turmoil Maj. Gen. James D. O'Connell succeeded General Back as chief signal officer in May 1955. Commissioned in the Infantry after graduating from West Point in 1922, O'Connell joined the Signal Corps in 1928. The next year he entered the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University where he received a Master of Science degree in communication engineering in 1930. During World War 11 he served in Europe with the signal

[344]

section of Headquarters, 12th Army Group. After the war he became director of the Fort Monmouth laboratories, followed by a tour as signal officer of the Eighth Army in Japan. Before becoming chief signal officer, O'Connell served as Back's deputy. With his promotion to lieutenant general in 1958, O'Connell became the first chief signal officer to hold that rank. His tenure as chief included the exciting achievements made during the IGY, and he helped launch the Signal Corps into the computer age through his support of the Fieldata program.125

When O'Connell retired in April 1959, his deputy, Maj. Gen. Ralph T. Nelson, replaced him effective on 1 May. Nelson, a member of the West Point class of 1928, had served in both World War II and Korea. He subsequently commanded the Signal Corps training center at Fort Gordon and the Electronic Proving Ground at Fort Huachuca. Like O'Connell, Nelson possessed the technical background necessary to steer the Corps through the revolutionary changes taking place in communications.126

Organization, Training, and Operations, 1960-1964

In 1960 the Signal Corps celebrated its centennial: A century had passed since Congress had authorized the addition of a signal officer to the Army Staff on 21 June 1860 and Albert J. Myer had received the appointment six days later. The year-long observance (21 June 1960 to 21 June 1961) included: a traveling exhibit that visited all major Signal Corps installations, the Pentagon, and the Smithsonian; the publication of numerous articles in newspapers and magazines about the Signal Corps; a special broadcast of "The Big Picture"; and the burial of a centennial time capsule at Fort Monmouth. The Signal Corps could indeed look back with pride on one hundred years of growth and accomplishment. Having become the Army's third largest branch, comprising about 7 percent of its strength, it had taken military communications from waving flags to speeding electrons and orbiting satellites.127

The Signal Corps began its second century, however, with some drastic changes. The centralization of authority that had resulted in the creation of the Department of Defense increasingly insinuated itself into the operations of the Army and resulted in the erosion of power traditionally held by the technical services. In 1955, for instance, the position of chief of research and development had been added to the Army Staff to supervise this functional area, cutting across the traditional authority of each of the technical bureaus.128 Later, in 1960, the Defense Communications Agency was created to operate and manage the new Defense Communications System. This worldwide, long-haul system provided secure communications for the president, the secretary of defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, government agencies, and the military services.129 The system incorporated the facilities of the ACAN-renamed the Strategic Army Communications Network (STARCOM)-which the Signal Corps continued to operate.130 In another significant shift, the Signal Corps regained its status as a combat arm, which it had lost

[345]

ten years before. In 1961 Army regulations designated the Signal Corps (along with the Corps of Engineers) as both a combat arm and a technical service.131

In that same year the new president, John E Kennedy, and his secretary of defense, Robert S. McNamara, set out to reorganize and strengthen the armed forces to allow for a more flexible response to international crises. Concurrently, McNamara initiated far-reaching managerial reforms within the Defense Department that shifted power from the military services to the civilian bureaucracy. In conjunction with these changes at the higher levels, McNamara directed a thorough reorganization of the Army Staff. On 16 January 1962 President Kennedy submitted a plan to Congress that abolished the technical services, with the exception of the Medical Department. Congress raised no objections, and the reorganization became effective on 17 February. Although the positions of the chief chemical officer, the chief of ordnance, and the quartermaster general all disappeared, the chief signal officer and the chief of transportation were retained as special staff officers rather than as chiefs of services. The chief of engineers retained his civil functions only, while the chief signal officer now reported to the deputy chief of staff for military operations (DCSOPS).132 By eliminating the technical services as independent agencies, McNamara succeeded where Somervell and others had failed.

For the Signal Corps, the McNamara reforms wrought a fundamental transformation. Functional commands took over most of the chief signal officer's duties: the Combat Developments Command became responsible for doctrine; the Continental Army Command (CONARC) took over schools and training; and the Army Materiel Command (AMC) acquired authority for research and development, procurement, supply, and maintenance. While signal soldiers continued to receive assignments within the branch and to wear the crossed flags and torch insignia, personnel assignment and career management became the province of the Office of Personnel Operations. The Signal Corps even lost control of its home, as Fort Monmouth became the headquarters of the Electronics Command, an element of the AMC. Despite the changes in the chain of command at Monmouth, the U.S. Army Signal Center and School remained there, for a time, to maintain the history and traditions of the Corps. Having surrendered much of his domain, the chief signal officer nevertheless retained control over strategic communications, largely because there was no functional command to which to assign them.133

Chief Signal Officer Nelson, who had favored the reorganization, left the Army at the end of June 1962 before the reforms had been fully implemented.134 His successor, Maj. Gen. Earle F. Cook, retired in frustration in June 1963. Before relinquishing his post, he spoke frankly to the chief of staff, General Earle G. Wheeler, telling him that he had found "after one year's functioning under the 1962 Army reorganization that there is lacking in elements of the Army Staff a proper understanding of Army communications and electronics and the role of the Chief Signal Officer."135 Having been apprised of the problems, Wheeler directed that a board be assembled to study signal activities. Made up of general

[346]

GENERAL GIBBS |

officers from all the major staff elements in the Department of the Army, the so-called Powell Board (for General Herbert B. Powell, commander of CONARC) made recommendations that resulted in further modifications to the organization and operations of the Signal Corps.

As proposed by the board, the Army established on 1 March 1964 the Office of the Chief of Communications-Electronics, a subordinate agency of the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Military Operations, to replace the Office of the Chief Signal Officer. The incumbent, Maj. Gen. David P Gibbs (son of Maj. Gen. George S. Gibbs, who had held the post from 1928 to 1931), thus became the last to bear the title of chief signal officer and the first to be chief of communications-electronics. Ironically, his father had advocated the creation of such a staff position twenty years earlier. While the new title perhaps more accurately described the broad nature and scope of the chief's work, it severed the historic connection with the branch's past. After 104 years, the long chain of chief signal officers, stretching back to the Corps' founder, Albert J. Myer, had been broken.136

Concurrently, the staff and command responsibilities of the chief signal officer were separated. Gibbs turned over control of strategic communications to the newly established Strategic Communications Command (STRATCOM), with headquarters in Washington, D.C.137 This major command became responsible for the management of all long-distance Army communications and for engineering, installing, operating, and maintaining the Army portions of the Defense Communications System. Henceforth, Gibbs and his successors became advisers

[347]

to the Army Staff on communications-electronics issues. Other principal responsibilities included radio-frequency and call-sign management and use, communications security, and Army representation on boards and committees dealing with communications-electronics matters. Gibbs retained control of the Army Photographic Agency in the Pentagon, while the Army Pictorial Center at Astoria became part of the AMC.138

Despite the radical realignment, Gibbs declared himself pleased with the new arrangement:

I firmly believe these changes in the management of Communications and Electronics in the Army to be a step in the proper direction. It has clarified many of those gray areas surrounding our previous organization involving the responsibilities of the Chief Signal Officer, and the alignment of the Army long-haul communications functions.139 |

Relieved of his Signal Corps operational duties, the chief of communications-electronics could adopt an Army-wide perspective.

Concurrent with the reorganization of the Army Staff, the Army's tactical divisions underwent restructuring. Early in 1962 the Army began implementing the Reorganization Objective Army Divisions (ROAD) plan. The battle groups of the pentomic divisions had proven too weak for conventional war, and the Kennedy administration's strategy of flexible response emphasized the waging of atomic wars only as a last resort. Hence the Army formed four new types of divisions: infantry, armor, airborne, and mechanized, each with a common base and three brigade headquarters. The division base contained the support units, including a signal battalion comprised of three companies, one to support each brigade.140 The Army was still in the throes of these changes when a new series of crises threatened the world with war.